We may never know where we’re going, but we’d better have a good idea where we are.

Market cycles present the investor with a daunting challenge, given that:

• Their ups and downs are inevitable.

• They will profoundly influence our performance as investors.

• They are unpredictable as to extent and, especially, timing.

So we have to cope with a force that will have great impact but is largely unknowable. What, then, are we to do about cycles? The question is of vital importance, but the obvious answers—as so often—are not the right ones.

The first possibility is that rather than accept that cycles are unpredictable, we should redouble our efforts to predict the future, throwing added resources into the battle and betting increasingly on our conclusions. But a great deal of data, and all my experience, tell me that the only thing we can predict about cycles is their inevitability. Further, superior results in investing come from knowing more than others, and it hasn’t been demonstrated to my satisfaction that a lot of people know more than the consensus about the timing and extent of future cycles.

The second possibility is to accept that the future isn’t knowable, throw up our hands, and simply ignore cycles. Instead of trying to predict them, we could try to make good investments and hold them throughout. Since we can’t know when to hold more or less of them, or when our investment posture should become more aggressive or more defensive, we could simply invest with total disregard for cycles and their profound effect. This is the so-called buy-and-hold approach.

There’s a third possibility, however, and in my opinion it’s the right one by a wide margin. Why not simply try to figure out where we stand in terms of each cycle and what that implies for our actions?

In the world of investing, … nothing is as dependable as cycles. Fundamentals, psychology, prices and returns will rise and fall, presenting opportunities to make mistakes or to profit from the mistakes of others. They are the givens.

We cannot know how far a trend will go, when it will turn, what will make it turn or how far things will then go in the opposite direction. But I’m confident that every trend will stop sooner or later. Nothing goes on forever.

So what can we do about cycles? If we can’t know in advance how and when the turns will occur, how can we cope? On this, I am dogmatic: We may never know where we’re going, but we’d better have a good idea where we are. That is, even if we can’t predict the timing and extent of cyclical fluctuations, it’s essential that we strive to ascertain where we stand in cyclical terms and act accordingly.

“IT IS WHAT IT IS,” MARCH 27, 2006

PAUL JOHNSON: I respect Marks’s position on this issue. However, this goal is not nearly as simple as he suggests. He does offer a reasonable compromise in the memo below that I found very operational.

It would be wonderful to be able to successfully predict the swings of the pendulum and always move in the appropriate direction, but this is certainly an unrealistic expectation. I consider it far more reasonable to try to (a) stay alert for occasions when a market has reached an extreme, (b) adjust our behavior in response and, (c) most important, refuse to fall into line with the herd behavior that renders so many investors dead wrong at tops and bottoms.

“FIRST QUARTER PERFORMANCE,” APRIL 11, 1991

I don’t mean to suggest that if we can figure out where we stand in a cycle we’ll know precisely what’s coming next. But I do think that understanding will give us valuable insight into future events and what we might do about them, and that’s all we can hope for.

When I say that our present position (unlike the future) is knowable, I don’t mean to imply that understanding comes automatically. Like most things about investing, it takes work. But it can be done. Here are a few concepts I consider essential in that effort.

First, we must be alert to what’s going on. The philosopher Santayana said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” In very much the same way, I believe those who are unaware of what’s going on around them are destined to be buffeted by it.

As difficult as it is know the future, it’s really not that hard to understand the present. What we need to do is “take the market’s temperature.” If we are alert and perceptive, we can gauge the behavior of those around us and from that judge what we should do.

The essential ingredient here is inference, one of my favorite words. Everyone sees what happens each day, as reported in the media. But how many people make an effort to understand what those everyday events say about the psyches of market participants, the investment climate, and thus what we should do in response?

Simply put, we must strive to understand the implications of what’s going on around us. When others are recklessly confident and buying aggressively, we should be highly cautious; when others are frightened into inaction or panic selling, we should become aggressive.

So look around, and ask yourself: Are investors optimistic or pessimistic? Do the media talking heads say the markets should be piled into or avoided? Are novel investment schemes readily accepted or dismissed out of hand? Are securities offerings and fund openings being treated as opportunities to get rich or possible pitfalls? Has the credit cycle rendered capital readily available or impossible to obtain? Are price/earnings ratios high or low in the context of history, and are yield spreads tight or generous?

PAUL JOHNSON: These insightful questions can easily act as a checklist that investors could use periodically to take the market’s temperature.

All of these things are important, and yet none of them entails forecasting. We can make excellent investment decisions on the basis of present observations, with no need to make guesses about the future.

The key is to take note of things like these and let them tell you what to do. While the markets don’t cry out for action along these lines every day, they do at the extremes, when their pronouncements are highly important.

The years 2007–2008 can be viewed as a painful time for markets and their participants, or as the greatest learning experience in our lifetimes. They were both, of course, but dwelling on the former isn’t of much help. Understanding the latter can make anyone a better investor. I can think of no better example than the devastating credit crisis to illustrate the importance of making accurate observations regarding the present and the folly of trying to forecast the future. It warrants a detailed discussion.

It’s obvious in retrospect that the period leading up to the onset of the financial crisis in mid-2007 was one of unbridled—and unconscious—risk taking. With attitudes cool toward stocks and bonds, money flowed to “alternative investments” such as private equity—buyouts—in amounts sufficient to doom them to failure. There was unquestioning acceptance of the proposition that homes and other real estate would provide sure profits and cushion against inflation. And too-free access to capital with low interest rates and loose terms encouraged the use of leverage in amounts that proved excessive.

After-the-fact risk awareness doesn’t do much good. The question is whether alertness and inference would have helped one avoid the full brunt of the 2007–2008 market declines. Here are some of the indicators of heatedness we saw:

• The issuance of high yield bonds and below investment grade leveraged loans was at levels that constituted records by wide margins.

• An unusually high percentage of the high yield bond issuance was rated triple-C, a quality level at which new bonds usually can’t be sold in large amounts.

• Issuance of debt to raise money for dividends to owners was routine. In normal times, such transactions, which increase the issuers’ riskiness and do nothing for creditors, are harder to accomplish.

• Debt was increasingly issued with coupons that could be paid with more debt, and with few or no covenants to protect creditors.

• Formerly rare triple-A debt ratings were assigned by the thousands to tranches of untested structured vehicles.

• Buyouts were done at increasing multiples of cash flow and at increasing leverage ratios. On average, buyout firms paid 50 percent more for a dollar of cash flow in 2007 than they had in 2001.

• There were buyouts of firms in highly cyclical industries such as semiconductor manufacturing. In more skeptical times, investors take a dim view of combining leverage and cyclicality.

Taking all these things into consideration, a clear inference was possible: that providers of capital were competing to do so, easing terms and interest rates rather than demanding adequate protection and potential rewards. The seven scariest words in the world for the thoughtful investor—too much money chasing too few deals—provided an unusually apt description of market conditions.

HOWARD MARKS: The riskiest things: When buyers compete to put large amounts of capital to work in a market, prices are bid up relative to value, prospective returns shrink, and risk rises. It’s only when buyers predominate relative to sellers that you can have highly overpriced assets. The warning signs shouldn’t be hard to spot.

You can tell when too much money is competing to be deployed. The number of deals being done increases, as does the ease of doing deals; the cost of capital declines; and the price for the asset being bought rises with each successive transaction. A torrent of capital is what makes it all happen.

If you make cars and want to sell more of them over the long term—that is, take permanent market share from your competitors—you’ll try to make your product better. … That’s why—one way or the other—most sales pitches say, “Ours is better.” However, there are products that can’t be differentiated, and economists call them “commodities.” They’re goods where no seller’s offering is much different from any other. They tend to trade on price alone, and each buyer is likely to take the offering at the lowest delivered price. Thus, if you deal in a commodity and want to sell more of it, there’s generally one way to do so: cut your price. …

It helps to think of money as a commodity just like those others. Everyone’s money is pretty much the same. Yet institutions seeking to add to loan volume, and private equity funds and hedge funds seeking to increase their fees, all want to move more of it. So if you want to place more money—that is, get people to go to you instead of your competitors for their financing—you have to make your money cheaper.

One way to lower the price for your money is by reducing the interest rate you charge on loans. A slightly more subtle way is to agree to a higher price for the thing you’re buying, such as by paying a higher price/earnings ratio for a common stock or a higher total transaction price when you’re buying a company. Any way you slice it, you’re settling for a lower prospective return.

“THE RACE TO THE BOTTOM,” FEBRUARY 17, 2007

One trend investors might have observed during this dangerous period, had they been alert, was the movement along the spectrum that runs from skepticism to credulousness in regard to what I described earlier as the silver bullet or can’t-lose investment. Thoughtful investors might have noticed that the appetite for silver bullets was running high, meaning greed had won out over fear and signifying a nonskeptical—and thus risky—market.

Hedge funds came to be viewed as just such a sure thing during the last decade, and especially those called “absolute return” funds. These were long/short or arbitrage funds that wouldn’t pursue high returns by making “directional” bets on the market’s trend. Rather, the managers’ skill or technology would enable them to produce consistent returns in the range of 8 to 11 percent regardless of which way the market went.

Too few people recognized that achieving rock-steady returns in that range would be a phenomenal accomplishment—perhaps too good to be true. (N.B.: that’s exactly what Bernard Madoff purported to be earning.) Too few wondered (a) how many managers there are with enough talent to produce that miracle, especially after the deduction of substantial management and incentive fees, (b) how much money they could do it with and (c) how their highly levered bets on small statistical discrepancies would fare in a hostile environment. (In the difficult year of 2008, the term absolute return was shown to have been overused and misused, as the average fund lost about 18 percent.)

As described at length in chapter 6, we heard at the time that risk had been eliminated through the newly popular wonders of securitization, tranching, selling onward, disintermediation and decoupling. Tranching deserves particular attention here. It consists of allocating a portfolio’s value and cash flow to stakeholders in various tiers of seniority. The owners of the top-tier claim get paid first; thus, they enjoy the greatest safety and settle for relatively low returns. Those with bottom-tier claims are in the “first-loss” position, and in exchange for accepting heightened risk they enjoy the potential for high returns from the residual that’s left over after the fixed claims of the senior tranches have been paid off.

In the years 2004–2007, the notion arose that if you cut risk into small pieces and sell the pieces off to investors best suited to hold them, the risk disappears. Sounds like magic. Thus, it’s no coincidence that the tranched securitizations from which so much was expected became the site of many of the worst meltdowns: there’s simply no magic in investing.

Absolute return funds, low-cost leverage, riskless real estate investments and tranched debt vehicles were all the rage. Of course, the error in all these things became clear beginning in August 2007. It turned out that risk hadn’t been banished and, in fact, had been elevated by investors’ excessive trust and insufficient skepticism.

The period from 2004 through the middle of 2007 presented investors with one of the greatest opportunities to outperform by reducing their risk, if only they were perceptive enough to recognize what was going on and confident enough to act. All you really had to do was take the market’s temperature during an overheated period and deplane as it continued upward. Those who were able to do so exemplify the principles of contrarianism, discussed in chapter 11. Contrarian investors who had cut their risk and otherwise prepared during the lead-up to the crisis lost less in the 2008 meltdown and were best positioned to take advantage of the vast bargains it created.

There are few fields in which decisions as to strategies and tactics aren’t influenced by what we see in the environment. Our pressure on the gas pedal varies depending on whether the road is empty or crowded. The golfer’s choice of club depends on the wind. Our decision regarding outerwear certainly varies with the weather. Shouldn’t our investment actions be equally affected by the investing climate?

Most people strive to adjust their portfolios based on what they think lies ahead. At the same time, however, most people would admit forward visibility just isn’t that great. That’s why I make the case for responding to the current realities and their implications, as opposed to expecting the future to be made clear.

“IT IS WHAT IT IS,” MARCH 27, 2006

THE POOR MAN’S GUIDE TO MARKET ASSESSMENT

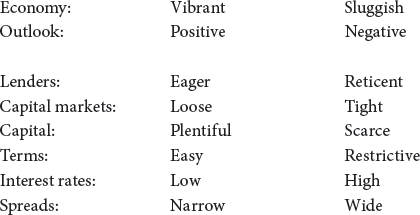

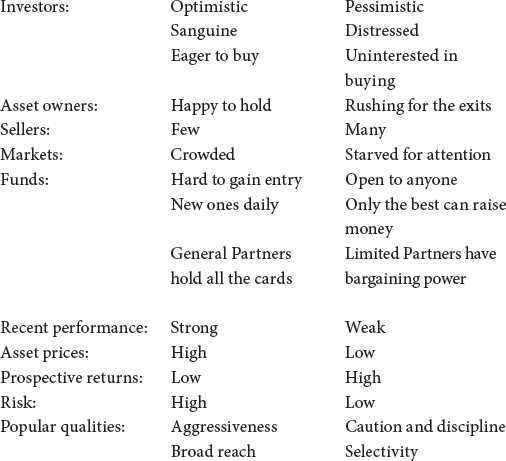

Here’s a simple exercise that might help you take the temperature of future markets. I have listed a number of market characteristics. For each pair, check off the one you think is most descriptive of today. And if you find that most of your checkmarks are in the left-hand column, as I do, hold on to your wallet.

“IT IS WHAT IT IS,” MARCH 27, 2006

CHRISTOPHER DAVIS: This table might be even more useful if it would allow for scaling—i.e., use a 1 to 5 scale for each category and allow “N/As” where necessary. With that modification, this is a great guide.

JOEL GREENBLATT: A wonderful chart and a great exercise.

PAUL JOHNSON: I feel strongly that running through this checklist twice a year would allow an investor to keep tabs on the swing of the market’s pendulum. After a decade, the investor would have a rich database of past market swings from which to draw. I wish I had started such a list ten years ago.

Markets move cyclically, rising and falling. The pendulum oscillates, rarely pausing at the “happy medium,” the midpoint of its arc. Is this a source of danger or of opportunity? And what are investors to do about it? My response is simple: try to figure out what’s going on around us, and use that to guide our actions.