The performance of investors who add value is asymmetrical. The percentage of the market’s gain they capture is higher than the percentage of loss they suffer. … Only skill can be counted on to add more in propitious environments than it costs in hostile ones. This is the investment asymmetry we seek.

It’s not hard to perform in line with the market in terms of risk and return. The trick is to do better than the market: to add value. This calls for superior investment skill, superior insight. So here, near the end of the book, we come around full circle to the first chapter and second-level thinkers possessing exceptional skill.

The purpose of this chapter is to explain what it means for skillful investors to add value. To accomplish that, I’m going to introduce two terms from investment theory. One is beta, a measure of a portfolio’s relative sensitivity to market movements. The other is alpha, which I define as personal investment skill, or the ability to generate performance that is unrelated to movement of the market.

As I mentioned earlier, it’s easy to achieve the market return. A passive index fund will produce just that result by holding every security in a given market index in proportion to its equity capitalization. Thus, it mirrors the characteristics—e.g., upside potential, downside risk, beta or volatility, growth, richness or cheapness, quality or lack of same—of the selected index and delivers its return. It epitomizes investing without value added.

Let’s say, then, that all equity investors start not with a blank sheet of paper but rather with the possibility of simply emulating an index. They can go out and passively buy a market-weighted amount of each stock in the index, in which case their performance will be the same as that of the index. Or they can try for outperformance through active rather than passive investing.

Active investors have a number of options available to them. First, they can decide to make their portfolio more aggressive or more defensive than the index, either on a permanent basis or in an attempt at market timing. If investors choose aggressiveness, for example, they can increase their portfolios’ market sensitivity by overweighting those stocks in the index that typically fluctuate more than the rest, or by utilizing leverage. Doing these things will increase the “systematic” riskiness of a portfolio, its beta. (However, theory says that while this may increase a portfolio’s return, the return differential will be fully explained by the increase in systematic risk borne. Thus doing these things won’t improve the portfolio’s risk-adjusted return.)

Second, investors can decide to deviate from the index in order to exploit their stock-picking ability—buying more of some stocks in the index, underweighting or excluding others, and adding some stocks that aren’t part of the index. In doing so they will alter the exposure of their portfolios to specific events that occur at individual companies, and thus to price movements that affect only certain stocks, not the whole index. As the composition of their portfolios diverges from the index for “nonsystematic” (we might say “idiosyncratic”) reasons, their return will deviate as well. In the long run, however, unless the investors have superior insight, these deviations will cancel out, and their risk-adjusted performance will converge with that of the index.

Active investors who don’t possess the superior insight described in chapter 1 are no better than passive investors, and their portfolios shouldn’t be expected to perform better than a passive portfolio. They can try hard, put their emphasis on offense or defense, or trade up a storm, but their risk-adjusted performance shouldn’t be expected to be better than the passive portfolio. (And it could be worse due to nonsystematic risks borne and transaction costs that are unavailing.)

That doesn’t mean that if the market index goes up 15 percent, every non-value-added active investor should be expected to achieve a 15 percent return. They’ll all hold different active portfolios, and some will perform better than others … just not consistently or dependably. Collectively they’ll reflect the composition of the market, but each will have its own peculiarities.

Pro-risk, aggressive investors, for example, should be expected to make more than the index in good times and lose more in bad times. This is where beta comes in. By the word beta, theory means relative volatility, or the relative responsiveness of the portfolio return to the market return. A portfolio with a beta above 1 is expected to be more volatile than the reference market, and a beta below 1 means it’ll be less volatile. Multiply the market return by the beta and you’ll get the return that a given portfolio should be expected to achieve, omitting nonsystematic sources of risk. If the market is up 15 percent, a portfolio with a beta of 1.2 should return 18 percent (plus or minus alpha).

Theory looks at this information and says the increased return is explained by the increase in beta, or systematic risk. It also says returns don’t increase to compensate for risk other than systematic risk. Why don’t they? According to theory, the risk that markets compensate for is the risk that is intrinsic and inescapable in investing: systematic or “non-diversifiable” risk. The rest of risk comes from decisions to hold individual stocks: nonsystematic risk. Since that risk can be eliminated by diversifying, why should investors be compensated with additional return for bearing it?

According to theory, then, the formula for explaining portfolio performance (y) is as follows:

y = α+βx

Here α is the symbol for alpha, β stands for beta, and x is the return of the market. The market-related return of the portfolio is equal to its beta times the market return, and alpha (skill-related return) is added to arrive at the total return (of course, theory says there’s no such thing as alpha).

Although I dismiss the identity between risk and volatility, I insist on considering a portfolio’s return in the light of its overall riskiness, as discussed earlier.

CHRISTOPHER DAVIS: But is beta the right measure of risk? This seems to run a bit counter to the earlier discussion of risk. But even if beta is not the most meaningful or relevant measure, it is certain that Oaktree has done a wonderful job on a risk-adjusted basis.

A manager who earned 18 percent with a risky portfolio isn’t necessarily superior to one who earned 15 percent with a lower-risk portfolio. Risk-adjusted return holds the key, even though—since risk other than volatility can’t be quantified—I feel it is best assessed judgmentally, not calculated scientifically.

JOEL GREENBLATT: Such an important concept for business students (who have likely been taught otherwise)!

Of course, I also dismiss the idea that the alpha term in the equation has to be zero. Investment skill exists, even though not everyone has it. Only through thinking about risk-adjusted return might we determine whether an investor possesses superior insight, investment skill or alpha … that is, whether the investor adds value.

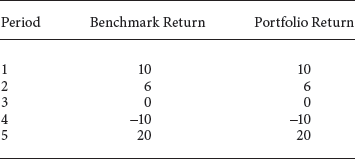

The alpha/beta model is an excellent way to assess portfolios, portfolio managers, investment strategies and asset allocation schemes. It’s really an organized way to think about how much of the return comes from what the environment provides and how much from the manager’s value added. For example, it’s obvious that this manager doesn’t have any skill:

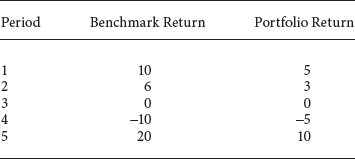

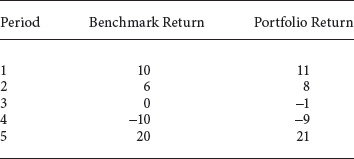

But neither does this manager (who moves just half as much as the benchmark):

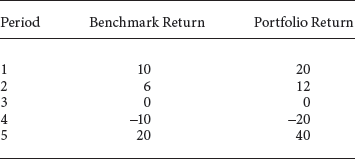

Or this one (who moves twice as much):

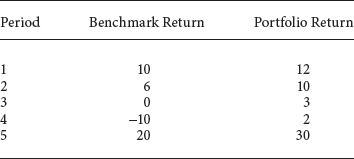

This one has a little:

While this one has a lot:

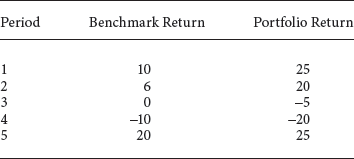

This one has a ton, if you can live with the volatility:

What’s clear from these tables is that “beating the market” and “superior investing” can be far from synonymous—see years one and two in the third example. It’s not just your return that matters, but also what risk you took to get it.

“RETURNS AND HOW THEY GET THAT WAY,” NOVEMBER 11, 2002

It’s important to keep these considerations in mind when assessing an investor’s skill and when comparing the record of a defensive investor and an aggressive investor. You might call this process style adjusting.

In a bad year, defensive investors lose less than aggressive investors. Did they add value? Not necessarily. In a good year, aggressive investors make more than defensive investors. Did they do a better job? Few people would say yes without further investigation.

A single year says almost nothing about skill, especially when the results are in line with what would be expected on the basis of the investor’s style. It means relatively little that a risk taker achieves a high return in a rising market, or that a conservative investor is able to minimize losses in a decline. The real question is how they do in the long run and in climates for which their style is ill suited.

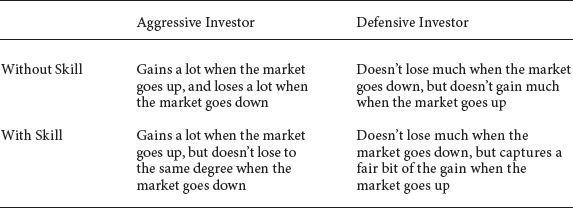

A two-by-two matrix tells the story.

The key to this matrix is the symmetry or asymmetry of the performance. Investors who lack skill simply earn the return of the market and the dictates of their style. Without skill, aggressive investors move a lot in both directions, and defensive investors move little in either direction. These investors contribute nothing beyond their choice of style. Each does well when his or her style is in favor but poorly when it isn’t.

On the other hand, the performance of investors who add value is asymmetrical. The percentage of the market’s gain they capture is higher than the percentage of loss they suffer. Aggressive investors with skill do well in bull markets but don’t give it all back in corresponding bear markets, while defensive investors with skill lose relatively little in bear markets but participate reasonably in bull markets.

Everything in investing is a two-edged sword and operates symmetrically, with the exception of superior skill. Only skill can be counted on to add more in propitious environments than it costs in hostile ones. This is the investment asymmetry we seek. Superior skill is the prerequisite for it.

JOEL GREENBLATT: Once again, finding the skilled investor comes down to understanding investment process, not merely assessing recent returns.

Here’s how I describe Oaktree’s performance aspirations:

In good years in the market, it’s good enough to be average. Everyone makes money in the good years, and I have yet to hear anyone explain convincingly why it’s important to beat the market when the market does well. No, in the good years average is good enough.

There is a time, however, when we consider it essential to beat the market, and that’s in the bad years. Our clients don’t expect to bear the full brunt of market losses when they occur, and neither do we.

Thus, it’s our goal to do as well as the market when it does well and better than the market when it does poorly. At first blush that may sound like a modest goal, but it’s really quite ambitious.

In order to stay up with the market when it does well, a portfolio has to incorporate good measures of beta and correlation with the market. But if we’re aided by beta and correlation on the way up, shouldn’t they be expected to hurt us on the way down?

If we’re consistently able to decline less when the market declines and also participate fully when the market rises, this can be attributable to only one thing: alpha, or skill.

That’s an example of value-added investing, and if demonstrated over a period of decades, it has to come from investment skill.

JOEL GREENBLATT: However, unlike Oaktree, many investment firms raise a large amount of assets as a result of a good long-term record. With more capital, managers are often forced to invest differently than they did when they were building their great track record. Oaktree actually returns capital whenever the opportunity set shrinks. Few investment firms follow this path.

Asymmetry—better performance on the upside than on the downside relative to what your style alone would produce—should be every investor’s goal.