CHAPTER 1

CHARACTER CLOSE-UPS

DESCRIPTION

Ambrose Bates was born and raised in Oxford, Mississippi. He enlisted in the army in World War II, leaving behind his elderly parents and the girl he loved. His African-American 761st Tank Battalion was sent to England. While stationed there, Ambrose received a letter from his girlfriend informing him that she had found someone else. Feeling like he had nothing to return home to, Ambrose fought like a madman after his battalion landed on Omaha Beach on October 10, 1944, preferring to sacrifice himself for his fellow soldiers who had loved ones waiting for them.

He died in Lorraine after taking out an entire German guard post single-handedly. Ambrose’s war story was influenced by the true story of Sergeant Warren G. H. Crecy, “The Baddest Man in the 761st.” Jean-Baptiste found Ambrose’s mangled body on the battlefield and brought him back to La Maison.

After the heartbreak with his human girlfriend, Ambrose didn’t intend to ever fall in love again, opting instead to pick up girls for fun with Jules. Finally, a few decades before the series started, he fell for Geneviève but was too respectful of her marriage to her human husband, Philippe, to let her know. He hoped that when Philippe died he might have a chance at winning Geneviève’s heart. He was unaware that Charlotte had long harbored a love for him.

Ambrose loves music and has a fondness for jazz from the era when he was human. He comes across as easygoing and affectionate to friends, and downright frightening to enemies. He has nicknames for everyone: he calls Kate “Katie-Lou,” Jean-Baptiste “JB,” and Vincent “Vin,” and he likes to annoy Charles by calling him “Chucky.”

Ambrose passes his free time bodybuilding and playing the trumpet. He is such a big movie buff that Jean-Baptiste built him a home cinema in La Maison. He drives a motorcycle and a 4x4.

AT FIRST GLANCE

Sitting next to the first boy was a strikingly handsome guy, built like a boulder, with short, cropped hair and dark chocolate skin. As I watched him, he turned and flashed me a knowing smile, as if he understood how I couldn’t resist checking him out. (Die for Me, Chapter 2)

QUOTE

“Well, I’m glad we’re starting with the easy questions,” he said, stretching his powerful arms and then leaning toward me. “The answer would be . . . because we’re zombies!” (Die for Me, Chapter 13)

DESCRIPTION

Antoine Mercier—or “Papy” as his granddaughters, Kate and Georgia, call him—is a successful French antiquities dealer, buying pieces from around the world and selling them out of his gallery on Quai de Conti.

The only thing Antoine prizes more than his collection is his family. While he isn’t an overly strict guardian, he is very protective of Kate and Georgia. He dotes on his wife, Emilie, and delights in showing her off at restaurants and shows.

Over his career, he has become aware of the existence of revenants, at least the fact that they exist in mythology and that there are secret collectors who will pay a fortune for anything referencing these supernatural beings.

Like Georgia, Antoine is very social; Kate says that he chats with anything that moves. He sometimes calls Kate ma princesse, just like her father did.

AT FIRST GLANCE

On my way past the living room, I spotted Papy in his armchair, reading a newspaper and looking every bit like an older version of my father. He still sported a full head of hair at seventy-one. His noble looks, which had been inherited by Georgia, had unfortunately skipped right over me. (Die for Me, Chapter 25)

QUOTE

“Is this just a skirmish,” he said, glancing at the vase, “or a full-out war? Not that it’s any of my business. I’m just wondering when you’re planning on calling a truce and restoring peace to the household. If it goes on much longer, I might have to leave on an urgent unforeseen business trip.” (Die for Me, Chapter 20)

DESCRIPTION

Arthur Poincaré was a counselor of Violette’s father and was inducted into Queen Anne of Brittany’s court when Violette became lady-in-waiting. He died alongside Violette during a kidnapping attempt on the young queen. His body lay next to Violette’s in Anne’s chapel, waiting until Violette’s father could arrive to retrieve them and bury them in Breton soil. Anne was alerted when Violette and Arthur suddenly “recovered.”

One of Anne’s advisers had heard stories of revenants and convinced Anne to keep Violette and Arthur as immortal bodyguards. After Anne died of natural causes, Violette and Arthur moved to the Château de Langeais, the medieval castle in the Loire Valley where Queen Anne had gotten married. Here, they served as the guardians of the castle. They lived for five hundred years in a platonic but codependent relationship, with Arthur acting as Violette’s “protector.”

Being part of the “old guard” and knowing a great deal about revenant history, Arthur and Violette went to La Maison when Charles and Charlotte were expelled from the house.

Arthur has spent the last few hundred years writing novels under several pseudonyms, including Pierre Delacourt (historical thrillers), Aurélie Saint-Onge, Henri Cotillon, and Hilaire Benois—some of the most famous authors in French literature.

AT FIRST GLANCE

The boy moved in a distinctly old-fashioned style, stepping up to her side and holding his arm out for her to take it with the tips of her fingers. He was probably around twenty, and if his streaky blond hair hadn’t been tied back into a tight ponytail and his face so clean-shaven, he would have looked exactly like Kurt Cobain. With a major case of blue-blood. (Until I Die, Chapter 2)

QUOTE

Lowering himself to one knee in front of Georgia, he took her hands in his. “Ma chère mademoiselle, may I have the sincere pleasure of being the one you choose to introduce you to the art of combat? I would consider it the greatest honor.” (If I Should Die, Chapter 10)

DESCRIPTION

Ava was born to a racially diverse family, with an African-American grandmother and a Cherokee grandfather. Her mom’s side is also Dutch, Scottish, Irish, and French. She jokes that she is the American melting pot.

She was brought up on Long Island and moved into Manhattan for college, studying art history at New York University. Her friends were all writers, artists, and musicians, which is how she met Andy Warhol’s Factory crowd. Andy latched on to Ava immediately, and she became his muse. He introduced her to “everyone who was anyone,” making her an instant celebrity.

She soon fell for another of Warhol’s favorites, an artist named Rosco. Ava and Rosco were the “It Couple” of the New York scene, and after a year they became engaged. Soon afterward, Ava was killed in an accident at a party held in an abandoned theater in the Bronx. She plunged to her death from a high balcony, saving a girl who had been standing near Rosco.

Theodore Gold saw her light and took her body from the mortuary, caring for her until she reanimated. The first time she was volant she discovered that the girl she had saved was also engaged to Rosco, and that she was just one of several women he was seeing.

She moved to Brooklyn, not only for fear of being recognized, but also because she wanted nothing more to do with the limelight. Since then she has kept a low profile, living by herself in an apartment not far from the bardia’s headquarters, the Warehouse, in Brooklyn.

Although she no longer wanted to be involved in the art scene, Ava finished her degree in art history and went on to become the world expert on Warhol and his crowd. Using various pseudonyms to mask her identity, she writes books and articles concerning American art after 1950.

AT FIRST GLANCE

The woman is stunning—in an exotic kind of way: long black hair, copper-colored skin, almond eyes, and high cheekbones. I rack my brain but am sure I haven’t seen her before. I would have remembered. (Die Once More, Chapter 1)

QUOTE

“You’re in our neighborhood, eight in the morning, full daylight. Know what that tells me about you and your friends?” she asks. “It tells me you’re expendable,” she says, and pulls the trigger. (Die Once More, Chapter 3)

DESCRIPTION

Bran is a member of the Tândorn clan, one of several families of “flame-fingers”—guérisseurs who historically treated the medical and psychic needs of revenants as well as humans. The Tândorn line was prophesized as the family to produce the VictorSeer—the guérisseur who would recognize the Victor, or, as the revenants call it, the Champion. His mother, Gwenhaël, claimed she did not have this gift, and indeed, it was Bran who was destined to bear this responsibility. When Bran inherited his mother’s powers, he had the signum bardia tattooed on his arm, as was the custom of his male ancestors.

He divided his time between his home in Carnac, Brittany, adjoining a field of Neolithic standing stones, and the family shop, Le Corbeau, in northern Paris, where he sold religious relics. His task was to care for and learn from his mother until she passed her gifts to him.

Bran has two sons. He and their mother, once Bran’s great love, are now good friends and share the upbringing of their children.

AT FIRST GLANCE

His head tilted slightly sideways at my words, as if he found the idea of someone being surprised by a speaking statue curious. What a strange man, I thought. With his slicked-back, dyed-black hair and the huge eyes that projected surreally from bottle-thick glasses, he looked like a cartoon version of the store’s avian namesake. Serious creep factor, I decided, shuddering. (Until I Die, Chapter 27)

QUOTE

Well, that explains why the power transfer didn’t work. . . . It’s simple. This boy is not the Champion. (If I Should Die, Chapter 11)

DESCRIPTION

A decade after becoming a bardia, Charles fell in love with a human girl named Madeleine. Bowing to pressure from Jean-Baptiste, he didn’t allow himself to see her, which is why Vincent’s relationship with Kate upset him.

Over the years, Charles’s bitterness about his fate as a bardia enmeshed him in a private philosophical debate over what his life was worth. He spent his hours reading at Paris libraries, becoming obsessed with existentialist theories and coming to the conclusion that he would be better off ending his life.

Charles is a more sensitive and deeper thinker than most of the Paris clan, profoundly concerned with the revenants’ role in humanity. When he runs away to join Uta and her clan, who emphasize the bardia’s higher purpose, he finally finds peace.

AT FIRST GLANCE

The girl had short-cropped blond hair and a shy laugh, and the natural way she kept leaning in toward the boy next to her made me think they were a couple. But upon turning my scrutiny to him, I realized how similar their features were, though his hair was golden red. They had to be brother and sister. (Die for Me, Chapter 4)

QUOTE

“And we’re not true zombies,” Charles said with a grin, “or he would have already eaten your face off.” (Die for Me, Chapter 13)

DESCRIPTION

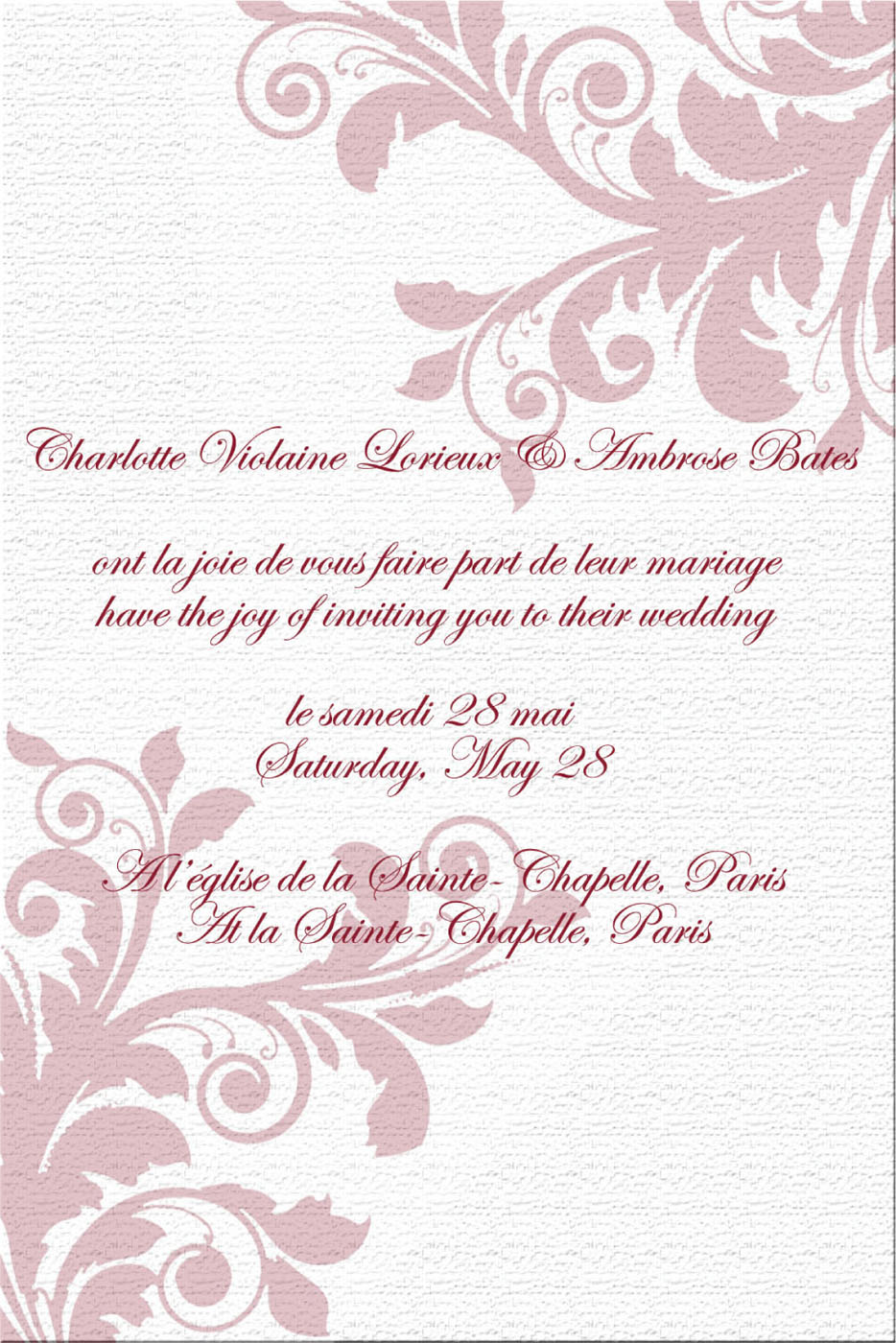

Charlotte and her twin, Charles, were born and raised in Paris’s fifth arrondissement, in the Latin Quarter. Their father was a professor at the Sorbonne.

During the Occupation of Paris, the twins’ parents ran a clandestine printing press for the Resistance out of a secret room in their apartment. The press was discovered by German forces, and their parents were killed. Charlotte and Charles escaped capture because they had spent the night at an aunt’s house. Afterward, they returned home and carried on their parents’ resistance by hiding two Jewish schoolmates and their parents in the hidden room. Using their parents’ own contacts, they secured enough ration cards to feed and clothe themselves and their guests for over a year. In the end, they were betrayed by a neighbor and, at age fifteen, were shot dead for their activities.

Jean-Baptiste found them at the mortuary and brought them back to La Maison. Ambrose was already living there, and Charlotte quickly fell in love with him. When she realized that he thought of her as a sister, she kept her feelings to herself and spent decades loving him in secret.

Charlotte took to life as a bardia with a vengeance, considering her lifesaving mission as a memorial to her parents. However, she has never gotten used to her brother’s deaths. At their execution, she was forced to watch him be shot first. Now, when Charles dies she has vivid flashbacks and, though she knows he will reanimate, is traumatized each time.

AT FIRST GLANCE

The light from the fire shone through her hair, making it glow like burnished bronze. Her cheeks and lips were the color of the velvety pink roses in Mamie’s country garden. High cheekbones set off her beautiful deep-set eyes, their irises a bewitching green. . . . They were eyes that looked as if they were used to taking much in, while giving little away. The eyes of an older woman reflecting the spirit of a little girl. (Die for Me, Chapter 11)

QUOTE

“Oh, Kate,” she whispered. “I wanted him to choose me.”

“So did I, Charlotte. I’ve been hoping for that this whole time. It’s really not fair. You would be perfect together.”

“I thought so too.” She sniffed and wiped her tears away. “But I can’t think like that now. I love Geneviève and I love Ambrose, and if they could be happy together, then I would never get in their way.” (Until I Die, Chapter 28)

DESCRIPTION

Emilie Mercier grew up in the wealthy suburbs of Paris, the daughter of a merchant who had made his own fortune. She met Antoine, her future husband, when she was seventeen, just before beginning her studies in art history at the École du Louvre. They didn’t begin dating until a year later.

Once they were married, Emilie continued her studies, specializing in painting restoration. Her glass-roofed studio takes up the entire top floor of their apartment building. Emilie’s work is highly regarded, and her clients include France’s most important museums, art dealers, and private collectors from around the world.

Emilie looks and acts much younger than her age. She emphasizes her position in life with her “uniform” of three-inch heels, over-the-knee dresses or skirts, and her beloved Hermès purse. Her lotion smells like roses, and she has used the same gardenia-scented perfume since Kate was a little girl.

Although “Mamie”—as her granddaughters call her—comes across as prim and polite, she is energetic and hardheaded and knows how to get what she wants.

She loves Georgia and Kate (who she calls “Katya”) as if they were her own daughters, and she was at the hospital when Kate was born.

AT FIRST GLANCE

Her forehead barely reached my chin, but her perfect posture and regulation three-inch heels made her seem much taller. Only a couple of years from seventy, Mamie’s youthful appearance subtracted at least a decade from her age. (Die for Me, Chapter 2)

QUOTE

“Your grandfather’s family made me feel like that in the beginning. It was a case of his parents’ old money versus my family’s new money, and they made me feel like an arriviste.”

“But that changed?”

“Yes. When they saw that I didn’t give a hoot what they thought about me. I think that was one reason your grandfather fell for me. I was the only woman who ever had the guts to stand up to his mother.” (Until I Die, Chapter 10)

DESCRIPTION

Faustino is third-generation Italian American and has been called “Faust” since grade school. He translated a passion for helping others into a career with the New York City Fire Department, after completing a degree in physical education at a community college.

One of the newer bardia at the Warehouse, he acts as Jules’s welcome rep. Jules remarks on Faust’s natural openness and unself-conscious earnestness.

Faust died rescuing the victims of the 9/11 attacks as a part of the FDNY’s Ladder Company 3. His first and last names are taken from two of the real-life firefighters who died on that day.

AT FIRST GLANCE

As we walk, I try to get a reading on Faust. He’s got this regimented air, but not as much as a soldier or policeman. And he struts straight-backed, but with his arms slightly spread, like his muscles are getting in the way. He’s already built big but has doubled his size with some serious time in the gym. Like most guys I’ve seen here, he favors facial hair: long razor stubble for him. Taking a wild guess, I would peg him as a fireman. I wonder if that’s what he was before he died. (Die Once More, Chapter 1)

QUOTE

As if reading my mind, Faust glances up at me. “At least I get to do what I love: save lives. Never thought I’d be signing up for an eternal contract when I became a firefighter.” (Die Once More, Chapter 2)

DESCRIPTION

Gaspard was a poet living in Paris when he was forced to enlist in the Franco-Austrian War, also called the Second Italian War of Independence. He died in the Battle of Solferino. The horror he saw on the battlefields was too much for a sensitive soul like himself, and it left him with stuttering and nervous tics in his afterlife, which only disappear when he is fighting.

Gaspard developed a passion for military history and weaponry. He serves as martial arts instructor for the newer revenants. He regularly writes scholarly articles on arms history and contributed research to the cataloguing of the oldest weapons in the war museum at Les Invalides. He is also the historian of the French revenants, managing the library at La Maison.

AT FIRST GLANCE

A man I had never seen before stepped toward me and and gave a nervous little bow. “Gaspard,” he introduced himself simply. He was older than the others, in his late thirties or early forties. Tall and gaunt, he had deep-set eyes and a shock of badly cut black hair sticking up in all directions. (Die for Me, Chapter 12)

QUOTE

“Must you insist on walking around the house naked, Jules? It makes me feel like I’m living in some kind of sordid fraternity house.”

“I’m not naked,” I say, pointing to the towel around my waist.

“A towel does not count as clothing,” Gaspard chides.

“Whatever you say,” I respond, and, yanking off the towel, drape it over my shoulders like a scarf. Gaspard shakes his head mournfully and wanders off toward the kitchen, mumbling, “I am living with cretins.” (Die for Her, Chapter 3)

DESCRIPTION

Geneviève grew up in Paris, and at age twenty-four met a car mechanic named Philippe. They fell in love and got married in 1940, and bought a house in the Mouzaia neighborhood of Belleville, where they planned to live out their days. But when Paris was occupied in World War II, Philippe was forced to repair tanks and cars for the German occupiers.

Although not a part of the organized Resistance, Geneviève began a resistance of her own. When one of her Jewish friends was taken to Drancy, a prison camp outside Paris, Geneviève rode her bike back and forth to pass the inmates food through a guard she knew from her school days. She was discovered and killed by firing squad.

Jean-Baptiste found her, took her in, and then—upon her insistence—allowed her to return to her husband, who not only accepted her “condition,” but took pride in her mission as a bardia. Philippe finally died in his eighties and was buried in Père Lachaise cemetery.

Geneviève is like a sister to the revenants at La Maison, and she is especially close to Charlotte.

AT FIRST GLANCE

A striking-looking woman in her late twenties sitting by herself. . . . Thick blond, almost white, hair flowed down her shoulders, and her high cheekbones and light blue eyes made her look vaguely Scandinavian. (Die for Me, Chapter 23)

QUOTE

“It takes most of us a while to come to grips with our new existence,” she says, her voice steeped in compassion. “Normally you would have time to acclimate to becoming a revenant before being tossed into the middle of things. I cried for two weeks after Jean-Baptiste found me and helped me animate. And it was months before I was mentally ready to face my destiny.” (If I Should Die, Chapter 40)

Eyes: Green, sultry

DESCRIPTION

Born in Paris, but raised in Brooklyn, Georgia was known by all in the New York art and music scene as the extroverted party girl who put on a charming Southern accent when she flirted.

After her parents died, Georgia decided that she and Kate would move to Paris to live with their grandparents. Unlike Kate, who dealt with her grief by isolating herself, Georgia responded by partying harder than ever, making Paris her new playground. She quickly adapted to her new environment, finding glamorous friends, surrounding herself with musicians and artists, and attending the best parties Paris had to offer.

Georgia is exceptionally fond of Kate, her younger sister by only seventeen months, and is fiercely protective of her “Katie-Bean.” In New York, she had brought Kate to as many parties as she could, appointing cute guy friends to accompany her sister. In Paris, she continued to try to drag Kate along with her, but Kate resisted, unable to socialize after her parents’ death.

Georgia and Kate joke about being twins since they’re so close in age, but their personalities couldn’t be more different. Their love for each other runs deep, but their arguments are epic. Papy refers to their fights as “World Wars.”

According to her mother, Georgia lacks intuition and can never see the bad in people. Because of this, she sometimes finds herself in dangerous situations and questionable relationships.

AT FIRST GLANCE

My sister was painfully beautiful. Her strawberry blond hair was in a short pixie cut that only a face with her strikingly high cheekbones could carry off. Her peaches-and-cream skin was sprinkled with tiny freckles. And like me, she was tall. Unlike me, she had a knockout figure. I would kill for her curves. She looked twenty-one instead of a few weeks shy of eighteen. (Die for Me, Chapter 1)

QUOTE

“Personally, I’m happy I haven’t run into a murderous killer since, well . . . since you chopped my ex’s head off with a sword.” (Georgia to Kate, Until I Die, Chapter 3)

DESCRIPTION

To the general public, Gwenhaël is a guérisseuse—a healer—specializing only in migraines and warts. In reality, she is a member of one of the Tândorn clan, one of a few dynasties of “flame-fingers”—those who heal and work with bardia.

In the eighteenth century, some Parisian numa used the book L’amur immortel to track down the flame-fingers. Gwenhaël’s ancestor fought them, killed them, and took possession of the book. He tracked down the only other known copy of the book and talked its owner into inking out one of two words indicating their location, while he inked out the other in his volume. Thenceforth, without possessing both books, it would be impossible to find the guérisseurs, protecting them against future numa attacks.

Gwenhaël’s family had not been consulted regarding revenants for a hundred years. But she was well read in the records her ancestors kept on their thoughts and observations about revenants. (These are kept in the guérisseurs’ archives.) Gwenhaël owned a handwritten copy of L’amur immortel, made by her ancestor, but never saw an original.

Gwenhaël knew from the stories passed down to her that bardia had an “aura like a forest fire,” and was thus able to recognize Jules as one. Gwen was killed by Violette’s numa after they questioned her about the identity of the Champion. Before dying, she revealed that the Champion was the revenant who killed the last numa leader.

AT FIRST GLANCE

Upon entering the room, I noticed an elderly woman sitting by a fireplace in a worn green chair, knitting. She glanced up from her work and said, “Come, child,” nodding to an overstuffed armchair facing her own. (Until I Die, Chapter 27)

QUOTE

“I’m sorry, dearie. I’m not making fun of you. It’s just that . . . people think that we guérisseurs are magic, which leads to all sorts of misconceptions. And I know that the shop below must add to my mystique—all the religious artifacts make locals think I’m a witch of some sort. But I’m not. I’m just an old lady whose father passed a simple gift to her: the gift of healing.” (Until I Die, Chapter 27)

DESCRIPTION

Jean-Baptiste was a Tirailleur-Grenadier in Napoleon’s Great Army. He was killed in the Battle of Borodino, Russia, when he sacrificed himself by pushing his valet out of the path of an oncoming cannonball. His valet (Jeanne’s ancestor) was determined to bring his master’s body back to France for burial. He was there three days later when Jean-Baptiste animated and helped to hide him until his transition was complete.

Upon returning to France, Jean-Baptiste lived out the next two centuries in his new role, as Seer of Paris. He actively sought out and organized France’s bardia, who until then had operated in small groups or alone, and appointed Seers for each region. He set up a network that facilitated the movement of bardia through France, relocating those who had died in one region to live in his houses in another, thus ensuring that humans didn’t recognize them after their frequent deaths.

Already from a wealthy background, Jean-Baptiste expanded his family’s fortune and invested his profits in Paris real estate. Some buildings he set aside for the bardia. The rest he rented out, ensuring the financial stability of his kindred for years to come.

After World War II, Jean-Baptiste led the battle against the Paris numa, whose number had exploded during the dark days of the war. Many bardia were destroyed, to the point that Jean-Baptiste brokered a secret peace agreement with Lucien, the numa leader. He surrendered several of his Paris properties for the numa to live in, hiding that fact from his kindred, who believed the numa to be itinerant. Another stipulation was that he declare a ban on hunting down and killing numa—dictating that bardia only kill them defending humans or in self-defense.

Jean-Baptiste facilitated his task as leader of the revenants by keeping a large network of policemen, doctors, paramedics, and mortuary workers in his pocket. None knew what was going on, only that they were paid well for their assistance and discretion.

Although Jean-Baptiste had assisted in the rescue of many new bardia and allowed his favorites to remain in La Maison, he always felt a special affinity for Vincent. Considering Vincent as a son, he quickly named him his second. Over time he became convinced that Vincent was France’s future Champion.

With all the responsibility that he held for France’s revenants, Jean-Baptiste timed his reanimations carefully, avoiding death for decades and aging into his sixties so that he didn’t risk being out of action during an emergency. Over the centuries, the urge to die waned for Jean-Baptiste, and he was able to avoid death for long periods without the extreme discomfort that younger revenants experience.

Jean-Baptiste was a member of the group of collectors who hoarded all revenant-themed objects, keeping them out of public view. Focusing on books and manuscripts, he kept his substantial collection in the library of La Maison.

AT FIRST GLANCE

His longish gray hair was smoothed back with pomade, and his face was punctuated by a long, hooked, noble-looking nose. I immediately recognized in his face and dress the mark of French aristocracy. (Die for Me, Chapter 10)

QUOTE

“Although the rest of my kindred may reside here, this is my house and I, for one, feel that your presence here is very unwise.” (Die for Me, Chapter 12)

DESCRIPTION

Jeanne is the cook and housekeeper for the revenants. She got her start helping her mother at La Maison at age sixteen. Her family has worked for Jean-Baptiste for nine generations. She has a husband, children, and four grandchildren in Paris.

Her paternal grandmother is Italian, and Jeanne has inherited several of her recipes.

Jeanne carries on her mother and grandmother’s tradition of storing locks of the bardia’s hair in small boxes in her room. She keeps them on a type of altar, with candles, and prays for the safety of the revenants she cares for.

Being the only other woman in the house, she provides a sense of stability for Charlotte, who sees her as a type of aunt figure. Kate specifies that even though she’s nominally the cook and housekeeper, she’s more like a house mom.

Jeanne’s perceptive, caring nature ensures that she knows what is going on with everyone in La Maison: Charles’s confusion, Charlotte’s unrequited love, and Jules’s feelings toward Kate. She was the first to notice that something had changed with Vincent after he first saw Kate.

AT FIRST GLANCE

I turned to see a plump middle-aged woman wearing an apron. She had soft rosy cheeks, and her graying blond hair was tied up in a bun. (Die for Me, Chapter 14)

QUOTE

“You’ve given new life to my Vincent. He might be strong of spirit, but he’s a tender soul. And you’ve touched him. For as long as I’ve known him, his only motivation has been vengeance and loyalty, which may be why he’s one of the few survivors. But now he has . . .” She paused, thinking twice about what she was going to say, and settled for, “You.” (Die for Me, Chapter 36)

DESCRIPTION

Jules Marchenoir was born and raised in a small village not far from Paris. Because of the artistic talent he showed at the young age of sixteen, he was sent to study painting in Paris by his father, a doctor, and his mother, a midwife.

He worked alongside Picasso, Braque, Gris, and others in the legendary artists’ studio the Bateau-Lavoir. He was good friends with Amedeo Modigliani, whom he accompanied on several drinking binges.

His schooling was cut short in 1914 when he was drafted into the war. He fought for two years until September 1916, when he was killed in action at the Battle of Verdun. He saved the life of Fernand Léger, a fellow artist, by handing him his gas mask during a mustard gas attack. Jules died in his place.

After he animated, Jules continued to paint, but had to stay out of view of the art world, which knew him to be dead. Because he used a series of pseudonyms for his paintings, he never gained the fame and approval he had dreamed of as a young man. He has long given up the desire for recognition and contents himself with refining his technique and painting subjects that he loves.

A notorious flirt, Jules thrives on the attention of women. Flattery is like an art form to him, and he’s had a century to perfect his moves. He ropes Ambrose into going out with him to pick up girls but is careful to follow Jean-Baptiste’s rules for not bringing lovers to any of the revenants’ permanent addresses. Although he appears to use women, he actually has his own strict code of conduct—never telling them anything that isn’t true, never cheating, never making promises he can’t keep, and breaking things off by making the girl think she is leaving him.

His affection for his kindred is deep, and his friendship with Vincent, who he calls “Vince,” is as close as that of brothers. His pet name for Kate is “Kates.”

AT FIRST GLANCE

Facing away from me was a wiry-built boy with slightly sunburned skin, sideburns, and curly brown hair, animatedly telling a story that sent the other two into peals of laughter. Now that I saw him from straight on, I was struck by how attractive he was. There was something rugged about him—unkempt, scruffy hair, bristly razor stubble, and large rough hands that gesticulated passionately toward the painting. By the condition of his clothes, I guessed he might be an artist. (Die for Me, Chapter 2)

QUOTE

“Sorry I’m not your boyfriend. And I mean that in all sorts of ways,” he said with an amused smile as he leaned forward to kiss me on each cheek. (Until I Die, Chapter 11)

DESCRIPTION

Kate was born in New York and given her mom’s maiden name (Beaumont) as her middle name. She has French roots on both sides of her family. Her father grew up in Paris, and her mother was raised in Georgia.

Her family lived in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood, and Kate spent her childhood playing in Prospect Park. As a teenager, Kate preferred reading and going to museums to going out, but sometimes accompanied her sister, Georgia, who thrived on the New York nightlife. Georgia would choose dates for Kate, guy friends she called Kate’s “party boys,” who would accompany her little sister to the parties and clubs they went to. Besides a few stolen kisses with these short-term escorts, Kate had never had a boyfriend.

Kate spent every summer with her grandparents in Paris and speaks French fluently. She had always dreamed of moving to Paris someday, so when Georgia decided they would move there after their parents died, Kate went along with her decision.

Kate’s mother told her that, though she was impetuous, she had an old soul and to trust her intuition because she had the ability to see things for what they were. This theory was put to the test when Kate met Vincent and found out what he was. She wavered several times between following her mind—after all, he was an undead boy who had lived many lives, and she was just a “normal” teenage girl—and following her heart. In the end it was her instincts that won out. She knew she was supposed to be with Vincent, and everything kept pointing to that fact.

Kate began displaying traits early on that, if anyone had been looking, signaled the fact that she was much more than a normal teenage girl. She not only was a latent revenant but held all the qualities needed to be the Champion. The fact that she won over all the revenants, including Jean-Baptiste, the fact that she could hear Vincent speak to her when he was volant, and the fact that she had a sense of numa auras—all while she was still human—should have tipped someone off. But it wasn’t until she offered her life instead of Vincent’s and was killed by Violette that Bran revealed she was indeed the Champion and possessed all the characteristics specified by the prophecy.

AT FIRST GLANCE

To see us together, you would never guess we were sisters. My long brown hair was lifeless; my skin, which thanks to my mother’s genes never tans, was paler than usual. And my blue-green eyes were so unlike my sister’s sultry, heavy-lidded “bedroom eyes.” “Almond eyes” my mom called mine, much to my chagrin. I would rather have an eye shape that evoked steamy encounters than one described by a nut. (Die for Me, Chapter 1)

QUOTE

Besides the alternate universe offered by a book, the quiet space of a museum was my favorite place to go. My mom said I was an escapist at heart . . . that I preferred imaginary worlds to the real one. It’s true that I’ve always been able to yank myself out of this world and plunge myself into another. (Die for Me, Chapter 5)

DESCRIPTION

Louis’s father disappeared when he was nine, leaving his mother, an uneducated, simple woman, to find what work she could while Louis took care of his younger brother and sister. When Louis was thirteen, his mother met a man named Frankie, who seduced her with promises of wealth and security. Once Frankie had moved in with the family, he quickly showed his true colors, getting fired from his job and spending his days on the couch, binge drinking.

When Frankie began selling drugs out of the apartment, one of his clients abused Louis’s little sister. Louis told his mother, who threatened to kick Frankie out. This spurred several weeks of violent arguments, culminating in his brother suffering a broken arm and his mother being knocked unconscious.

Louis used Frankie’s phone to call his drug contact and told him Frankie had been cheating him. Henchmen were sent to confront Frankie, and in the ensuing showdown he was killed, as well as Louis and his little brother. Three days later, Louis awoke as a numa because of a cosmic technicality: He had betrayed someone to their death and died soon afterward.

In preparing for her takeover of Paris’s revenants, Violette had instructed Nicolas (her second and a numa Seer) to find all animating numa and make sure they were cared for and trained, in order to build a Paris army. Louis animated soon after this order was given and was taken in by Nicolas.

Louis was a part of the numa guard who helped Violette escape Paris with Vincent’s body. He accompanied her to Langeais, and it was while they were there that Violette decided to choose him as her consort.

Because of the accidental nature of his animation as a numa, which was based more on circumstances than Louis’s true nature, he has the possibility to be one of the extremely rare numa that can be assisted by a flame-finger to transform into a bardia. Kate saw an example of this in a fresco in the guérisseurs’ archives, which gave her the inspiration needed to spare his life.

AT FIRST GLANCE

It was a boy. He must have been thirteen. His longish, light brown hair swept down over his eyebrows, nearly hiding his dark brown eyes. The monochrome numa aura outlined his body. A young numa. This must be Violette’s new companion. (If I Should Die, Chapter 35)

QUOTE

“I’m just . . . I’m sorry about all of this. I don’t want to be this way. She found me and made me her favorite, and all I want to do is die. But that’s not even possible for me anymore.” (If I Should Die, Chapter 37)

DESCRIPTION

Lucien Poitevin was born in a small town in the French countryside and joined the local police as soon as he finished high school. Always hungry for power, he struggled his way up the hierarchy using any means necessary to rise above the competition. When World War II broke out, he had already become an important police chief in Vichy, a town in the south of France that became the capital of the German-controlled French government.

During the war, the Vichy government set up a paramilitary force called the Milice in order to fight the Maquis in the countryside and the Resistance in Paris. Lucien rose quickly through this organization’s ranks, not balking at the darker roles of this group: rounding up Jews for deportation and extracting information and confessions from anyone they captured by their notorious torture methods.

As part of the Milice, Lucien betrayed hundreds, or indirectly, thousands, of his own countrymen to their deaths. He quickly became a top man in the Vichy regime’s information and propaganda ministry, married the daughter of a high-ranking Vichy official, and moved to Paris.

In June of 1944, a group of fifteen Resistance fighters, dressed as members of the Milice, broke into the Ministry of Information building where Lucien and his wife had been moved for their safety. They found the couple in their bed and killed them. There were several revenants among this group, including Vincent.

(This part of Lucien’s story was influenced by the true story of Philippe Henriot.)

After Lucien animated as a numa, he spent the next few years making alliances with his fellow evil revenants. With their help, he hunted down everyone involved in his death—both human and bardia—and destroyed them. Vincent was the only one to have survived, and he became Lucien’s archenemy.

Lucien managed to organize the Paris numa—as much as that was possible for such self-serving, anarchic beings—and became at the very least their spokesman if not their official leader. It was Lucien who brokered the peace agreement with Jean-Baptiste after the years of violent struggle between Paris’s bardia and numa post–World War II, thus cementing his position as their de facto leader.

In the relative period of peace that ensued, Lucien followed the example of numa before him: He set up businesses like nightclubs and restaurants that helped mask his kindred’s activities in prostitution, drugs, money laundering, and other dealings that could lead easily to human betrayal.

AT FIRST GLANCE

Finally getting a view unhampered by the crowds, I saw that he was everything that Georgia always went for, combined into one man. At least six-five, he looked like a mix between a surfer and a football player: windswept blond hair and suntanned skin but massive enough in build to single-handedly plow through an entire defensive line. His brown eyes were so light and crystalline that they looked like frozen butterscotch. (Die for Me, Chapter 24)

QUOTE

“Well, spit on my empty grave—if it ain’t the attack of the Disney princesses!” (Die for Me, Chapter 37)

DESCRIPTION

Nicolas served as Lucien’s second, and then oversaw the Paris numa for Violette until she could take her place as their leader. He is recognizable by his long fur coat, which Kate described as looking like it was designed for a Renaissance lord in a costume drama. He is a Seer—able to spot numa-in-the-making before they animate.

Nicolas is known for his short temper and love of ostentatious gestures. He prefers to hide safely behind a leader and serve as second in control rather than stick his neck out and rule.

Violette had him and the other numa watch Philippe’s funeral at Père Lachaise. He followed Kate to the tomb of Abelard and Héloïse, where she caught sight of him walking among the stones. He would have approached her if the volant numa spirit with him hadn’t alerted him that Vincent was on his way.

Violette used Arthur to pass messages to Nicolas, which is why Kate and Georgia saw the bardia and numa talking together at La Palette.

It was Nicolas who Violette met at Montmartre, outside Sacré-Coeur, when Georgia barged into their meeting and started the skirmish that ended with Vincent’s death.

Violette sent Nicolas with white lilies to inform Kate that she had taken Vincent’s corpse to her castle in the Loire Valley to destroy it. He assisted Violette in entrapping Mamie at the Crillon Hotel, and then accompanied Louis to visit the numa arms dealer in Passage du Grand Cerf, where he was killed by Ambrose after having murdered Geneviève. His body was taken to the bardia-run crematorium, and he was destroyed.

AT FIRST GLANCE

I couldn’t see his face, but his hair was a wavy salt-and-pepper—dark brown mixed with gray—and he was as tall as me. . . . A man in a long fur coat who was walking away from me. (Until I Die, Chapter 5)

QUOTE

“Charming. As if you could fight me. Actually, I am under strict orders not to touch you. Violette is of the opinion that letting you suffer would be more fun.” (Until I Die, Chapter 39)

DESCRIPTION

Theodore Gold was a friend of Edith Wharton’s, having grown up in the ultra-wealthy circles of New York’s upper class. He died saving a child from being crushed by a horse-drawn buggy on one of the treacherous streets circling Union Square.

Gold went to Paris in the 1860s and was a member of the group who founded New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, helping secure the Cesnola Collection.

He traveled to Paris in September 1939, just before World War II, and assisted with the evacuation of the Louvre Museum’s collections. He and his French colleagues packed all the artwork and shipped it to various locations in France to protect it from the invading German army. It was during this time that he met Jean-Baptiste. (This part of Gold’s past—as well as his precious metal-inspired name—is based on the name and true story of Charles Sterling, a Jewish curator who was responsible for evacuating the Louvre’s collections. He and his family escaped with the help of the director of the Met, and he worked at the museum for several years before returning to his job at the Louvre postwar.)

Gold returned to Paris a few years after the war, with several other American bardia who wanted to help their Paris kindred with their struggle with the numa. All his countrymen were killed and only Gold survived. Jean-Baptiste brought him to act as a witness at the peace agreements with Lucien, swearing Gold to secrecy.

Gold used his unlimited time to research Rome and Byzantium and published several books on antiquities, changing his writing style and using the names Theodore Gold Jr. and Theodore Gold III when his age became suspicious. He used a similar subterfuge with his job as head curator of antiquities at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, taking long leaves of absence until the staff he once worked with retired or died and his new colleagues wouldn’t recognize him. Gold established a secret revenant-themed collection in the basement of the museum, showing it only to the bardia who visit him from around the world.

Gold is the Seer for New York City and bought the building called the Warehouse in the 1950s to use as the bardia’s regional headquarters. As the official American bardia historian, he serves as the speaker for the council. And although he claims that everything is done democratically in America, it’s clear Gold is actually the leader of the New York kindred.

Gold lives in a luxurious ultramodern apartment on the top floor of a building facing the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York’s Upper East Side.

AT FIRST GLANCE

With his timeless look and white suit, he reminded me of a young Robert Redford in the seventies version of The Great Gatsby. Or a character straight out of an Edith Wharton novel: handsome and wheaten haired, with that tanned just-stepped-off-the-yacht look that very wealthy people have. (If I Should Die, Chapter 22)

QUOTE

“I know that Jean-Baptiste is like a father to you. . . . But I charge you, Vincent Delacroix, with relaying this information to your kindred. Otherwise, when the time comes and the battle begins, their blood will be on your hands.” (If I Should Die, Chapter 31)

DESCRIPTION

Uta is the leader of the German clan that Charles joins when he runs away from Jean-Baptiste’s house in the south of France. Also the Seer of her clan, Uta is the reason that the German revenants arrived in Paris in time to help fight the final battle, after seeing Kate’s light and following it from hours away.

Uta’s tough-looking appearance and an intense personality belie her touchy-feely approach to her kindred, picked up in her hippie days. Vincent describes her clan as resembling Alcoholics Anonymous for bardia: talking about their feelings, going on motivational wilderness retreats, and emphasizing their positive role in the world.

AT FIRST GLANCE

She looks like Lisbeth Salander’s tougher little sister, her wiry body painted with tattoos, face dotted with piercings, and blue hair cropped short and sticking out as if she used a live electrical wire to style it. (If I Should Die, Chapter 46)

QUOTE

“Maybe in your case it’s not physical strength. Seems like you’ve got a lot in here,” she says, thumping her chest with her fist. “Doesn’t always take muscle to be mighty.” (Uta to Kate, If I Should Die, Chapter 46)

DESCRIPTION

Vincent Pierre Henri Delacroix was born and raised in Brittany, a northwest region of France. Following French tradition, his middle names are from his father (Pierre) and grandfather (Henri). His village was occupied by the Germans during World War II. At age eighteen, he watched the ruthless murder of his parents and fiancée, Hélène, by two drunk officers. To avenge their deaths, he joined the Maquis, the rural arm of the French Resistance.

He and a friend were arrested by the occupying forces on suspicion of stealing weapons. His friend had a wife and child at home, so Vincent took the blame, claiming he had masterminded the weapons raid. He was shot in the town square and his friend was set free.

Jean-Baptiste noticed the story in the next day’s paper and saw Vincent’s light. He followed it to the hospital where Vincent’s corpse was laid out. Claiming he was family, he took Vincent’s body back to Paris and cared for him until he animated.

When Kate asks Vincent if he ever found the soldiers who killed Hélène, he admitted to killing them but said it wasn’t enough. He went after every other murderous villain he could find, including occupiers and collaborators, working in conjunction with the Paris Resistance.

During the numa-bardia skirmishes following World War II, Vincent became, as Jeanne described it, “an avenging robot,” throwing himself in harm’s way, as if dying for hundreds of strangers could make up for Hélène’s death. His only motivation has been vengeance, which might be why he survived this long. Jeanne said that after he met Kate, he came home with a spark of life in his eyes—the first sign of life she had seen in him for decades. Kate is the first girl Vincent has fallen for since Hélène’s death.

Over the years, Vincent kept watch over Hélène’s family from afar, leaving anonymous flowers when her father passed away and watching her sister Brigitte’s son after she died in childbirth. He kept tabs on the son, who moved to the south of France and has a family of his own, including a daughter who looks like her grandmother. Having that link to the past makes Vincent feel grounded.

Jean-Baptiste assigned Vincent the task of managing the French revenants’ legal affairs, sending Vincent to law school to get his degree.

Vincent also spent his free time learning French, English, Italian, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, and Latin. His hobbies are art, reading, cinema, and fight training. He became passionately interested in ancient and antique weaponry after being introduced to the subject by Gaspard.

AT FIRST GLANCE

He was breathtaking, with longish black hair waving up and back from a broad forehead. His olive skin made me guess that he either spent a lot of time outside or came from somewhere more southern and sunbaked than Paris. And the eyes that stared back into my own were as blue as the sea, lined with thick black lashes. (Die for Me, Chapter 2)

QUOTE

“Ma Kate, qui était à moi, qui n’est plus à moi,” he whispers as he kisses me. And then he says it in English. “My Kate, who was mine, who is no longer mine . . . because now you belong to fate.” (If I Should Die, Chapter 40)

DESCRIPTION

Violette de Montauban was born in the fifteenth century to a noble family. Her father was a marquis, and, like other girls of noble birth, she joined Queen Anne of Brittany’s court at age twelve, where she served as a lady-in-waiting.

Violette died while unintentionally saving the young queen’s life during the same kidnapping attempt that took Arthur’s human life.

In an effort to understand her unexplained fate, Violette devoted her life to the study of revenant history. She obtained more knowledge about both numa and bardia than any other “living” revenant, and, as the world expert on her kind, was an influential figure in the bardia’s worldwide Consortium.

But slowly, her desire for knowledge evolved into a quest for power. Like Jean-Baptiste, she began to suspect that Vincent might be the bardia’s future Champion. Over the years, Jean-Baptiste sent Vincent as his messenger to deliver previously undiscovered revenant texts to Violette. On one of these occasions, in the 1980s, Violette let Vincent know she was interested in him, seeing the chance to win over the future Champion and harness his power. Oblivious of her motivation, Vincent spent several days with her, thinking it might be his only chance to find a long-term partner. When he realized he didn’t feel anything for her, he ended it, much to Violette’s chagrin. Afterward, Vincent asked Jean-Baptiste to send someone else on those missions, and Violette hadn’t seen him since.

Violette never wanted to be a bardia. She said she had her immortal future decided for her at an age when she hadn’t even lived life. She resented being at the mercy of humans to keep her alive, and rarely went out into modern society, sacrificing herself for humans only when she was elderly. Violette never lost the arrogance of her noble class and was a paragon of bigotry. Jeanne explained that where she once looked down on peasants, she now scorned humans.

Her only desire was to possess the power over her own destiny; thus her plan to obtain the Champion’s power to overthrow the bardia and rule over the revenants of Paris. She preferred becoming a numa and betraying humans to remaining a bardia and having to save them.

Before the events of the story took place, Violette had already begun her takeover of the Paris numa. She approached them claiming to be the bardia emissary of a powerful American numa. She negotiated a truce with them and began giving them orders, commanding Lucien to bring her Vincent’s head, instigating his attack on La Maison. When that was botched by Kate’s intervention, Violette manipulated Jean-Baptiste into inviting her and Arthur to La Maison.

AT FIRST GLANCE

The girl’s snow-white complexion was set off by black hair that was pulled back from her face with a bunch of vivid purple flowers. She was tiny and fragile-looking, like a sparrow. And though she looked younger than me, I knew that for a revenant that didn’t mean a thing. (Until I Die, Chapter 2)

QUOTE

“You’d like that, Arthur, wouldn’t you? Whatever happened to my old companion, who agreed that humans were barely worth the blood we spilled for them?” (Until I Die, Chapter 36)