049

Greenwich, London, England

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Royal Observatory and National Maritime Museum

It’s no exaggeration to say that Greenwich is the center of the world: after all, the Prime Meridian of the Earth runs right through the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. A meridian is an imaginary north/south line that passes through both of the Earth’s poles; the Prime Meridian defines 0° of longitude and the time basis for all the world’s clocks. Greenwich Mean Time is now officially called Universal Time.

The Royal Observatory has been at Greenwich since 1675 and was of great importance in maintaining Britain’s naval power: observations of planets, moons, and stars were needed for the nautical almanacs used for navigation. Close to the Royal Observatory is the National Maritime Museum, which contains the clock that revolutionized navigation in 1759—John Harrison’s H4 marine chronometer.

Also on display at the National Maritime Museum are three clocks that Harrison built prior to the H4: logically enough, these are called the H1, H2, and H3. These three clocks are still running today; the H4 still works, but is only wound on rare occasions to avoid wearing out its components.

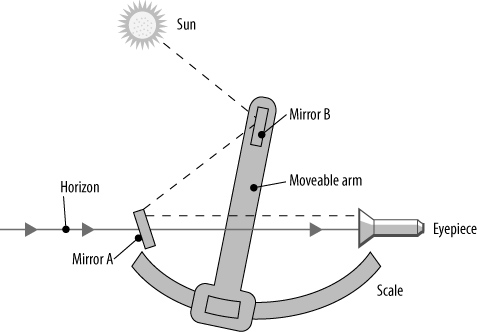

Highly accurate clocks were (and still are) vital to marine navigation, because longitude is found by comparing the time difference between noon on the Prime Meridian and noon on a ship at sea. Since the Earth rotates once every 24 hours through 360º, each hour of difference accounts for 15º of longitude. If a ship is sailing at the Equator, 1º of longitude (which corresponds to a time difference of 4 minutes) is 111 kilometers. Knowing the time at Greenwich accurately was—and remains—vital to knowing a ship’s location.

But keeping time accurately was an enormous challenge, so much so that in 1714 the British government offered a £20,000 prize for a method of determining longitude to within 56 kilometers. Harrison ultimately won most of the money by building a clock capable of keeping accurate time in the hostile world of a ship.

In a sea trial of the H4 sailing from England to Jamaica, the clock was found to be off by only 5 seconds (which corresponds to a navigation error of less than 1 kilometer). The 1.5-kilogram, 12-centimeter H4 proved itself able to keep time despite the movement of the ship, the salty air, battering by waves and wind, and changes in temperature.

The museum traces the history of timekeeping with the H4 and over 400 chronometers and watches. The Prime Meridian, longitude 0º, is visible outside the observatory and marked by a stainless steel bar; visitors can straddle it with one foot in the western hemisphere and the other in the east. At night, a green laser traces the meridian through the air.

Just before 1 p.m. each day, a large ball atop the Observatory is raised into the air. At precisely 1 p.m. the ball drops, and you can set your watch by it while standing on the meridian. Originally, this was done so that ships anchored in the port of London could set their clocks by watching for the visual signal from Greenwich.

Practical Information

The observatory and museum are inside Greenwich Park, which affords a wonderful view over London and a good place for a picnic lunch. Entry to the Royal Observatory, the National Maritime Museum, and Greenwich Park is free. Information about visiting the museums and special events is available from http://www.nmm.ac.uk/.