066

Sackville Street Gardens, Manchester, England

![]()

“IEKYF ROMSI ADXUO KVKZC GUBJ”

In this small green park, close to the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology, sits a bronze statue of the British thinker Alan Turing.

Turing is sitting on a bronze park bench holding an apple in one hand, his shirt collar undone and his tie loosened. At his feet sits a plaque reading “Father of Computer Science, Mathematician, Logician, Wartime Codebreaker, Victim of Prejudice.” If Turing is known at all, it is because of his work on the decryption of the Nazi Enigma cipher during the Second World War (see Chapter 40). But Turing’s legacy is far greater than that—he is responsible for large contributions to computer science as we know it.

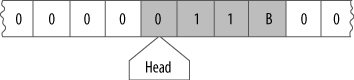

Turing invented a theoretical computer known today as a Turing Machine. A Turing Machine is a very simple computer with four important components. The first is a tape divided into squares (called cells); the Turing Machine can store one symbol from its alphabet of characters in each square. Symbols are written and read from the tape using the Turing Machine’s head; either the head or the tape moves, so the head can read and write from any cell (Figure 66-1). The Turing Machine uses a table of instructions to decide what to do—it can perform actions like moving the head one cell, reading the symbol under the head, writing a new symbol, or erasing a symbol from the tape. Finally, there’s a “state register” that tells the machine where it is in the table of instructions.

Figure 66-1. A Turing Machine’s tape and head

The tape is like the memory of a modern computer; the head has been replaced by electronic access to the memory, and the table of instructions is just the program. Turing described this Turing Machine while he was at Cambridge University in the late 1930s, and it remains the theoretical design of the computers we use today.

Turing came to invent this computer because of his interest in a mathematical puzzle called the Entscheidungsproblem (or Decision Problem). In the early 20th century (and even earlier in the minds of some great mathematicians like Leibniz), many mathematicians were interested in the possibility of creating a machine to do mathematics. The Decision Problem asked whether it would be possible to find an algorithm that could be fed some mathematical problem (written in a suitable mathematical language) and output either True or False. If such an algorithm did exist, then difficult unsolved mathematical problems could be fed to it to determine whether they were true or not. Turing’s contribution was to show that the Halting Problem could not be solved on a Turing Machine (see sidebar).

After his codebreaking work during the Second World War, Turing worked on some of the first electronic computers including ACE (the UK’s first computer with a program stored in it) and later on the Manchester Mark I at the University of Manchester. In 1950 Turing wrote about artificial intelligence and proposed a test for determining whether a computer could really think. What we now call the Turing Test involves two people, A and B, and a computer, C. Suppose that A is able to communicate with B (the person) and C (the computer) in writing only. A’s job is to determine which of B and C is human; if he cannot, then C is considered to be thinking.

The park is also close to Canal Street (running alongside the Rochdale Canal), which has been the center of Manchester’s gay community since the 1960s. Alan Turing was gay, and was prosecuted for “gross indecency” in 1952. To avoid prison, Turing accepted treatment for homosexuality in the form of estrogen injections, but in doing so he lost his security clearance and was no longer allowed to work on cryptography for the British government. Two years later, Turing was found dead in his home. He had apparently taken his own life by eating an apple laced with cyanide.

One Turing mystery remains. Set into the bench is the string of characters IEKYF ROMSI ADXUO KVKZC GUBJ, which is alleged to be the encryption of FOUNDER OF COMPUTER SCIENCE using an Enigma machine. But professional codebreakers have pointed out that that would mean the U in COMPUTER had been encrypted as the U in ADXUO. That’s impossible, since Enigma would never encrypt a letter as itself. The exact decoding is still unknown.

Practical Information

The park is easy to find because of its proximity to Canal Street (and Sackville Street), the University, and the canal. (Canal Street itself is a lively location for lunch or a drink.) Scientific visitors may want to coordinate their visits with an evening at Café Scientifique, where the University of Manchester hosts public talks and demonstrations of science in the café of the Manchester Museum; for details, see http://www.cafescientifique.manchester.ac.uk/.