073

The Hunterian Museum, Glasgow, Scotland

![]()

![]()

![]()

William Hunter and Lord Kelvin

The 18th-century anatomist and obstetrician William Hunter (brother of John Hunter; see Chapter 64) bequeathed the money for the creation of the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow. He also provided the core of its collection—his medical equipment and specimens, and his wide-ranging collection of art works, coins, books, and minerals. In the 200 years since its creation, the museum has vastly expanded its collection of scientific and artistic works, and also contains the most important public exhibition of the work of another great Glaswegian, William Thomson (who became Lord Kelvin).

William Hunter introduced the practice of using cadavers to teach medical students. He eventually specialized in obstetrics, publishing his illustrated The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus in 1774 (see Figure 73-1).

Figure 73-1. Illustration from The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus

The museum celebrates Hunter’s life through his collection, with a special emphasis for scientists on his medical equipment and pathological specimens. The collection also includes early X-ray and ultrasound equipment. The most up-to-date part of the exhibition examines the MRSA (multiple-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) bacterium, which is hard to treat because of its drug resistance, and the Glasgow Coma Scale (a scale of 3 to 15 indicating the degree of responsiveness of a coma patient).

William Thomson was born in Belfast, and came to Glasgow when his father was appointed professor of mathematics at the University. Thomson went on to Cambridge University and a spectacular career that spanned both theoretical and practical work. The Hunterian Museum describes him as the greatest Glaswegian scientist, which is undoubtedly true, but his impact was felt far from Glasgow and to this day.

Lord Kelvin’s practical inventions included the mirror galvanometer, which extended the telegraph to all parts of the British Empire (see page 236). Kelvin also gave his name to the standard unit of temperature (see sidebar), coined the term “kinetic energy,” built a highly accurate machine for predicting tides, and was a mentor for James Clerk Maxwell (see Chapter 35). He stands among the world’s greatest scientists, along with Newton, Einstein, and Faraday. He is buried in Westminster Abbey next to Newton.

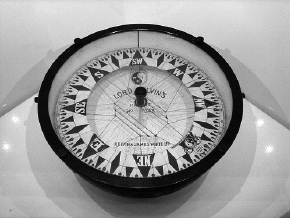

One of Kelvin’s often-overlooked inventions is his compass (Figure 73-3). In 1874, he wrote and lectured extensively about magnetic compasses, the Magnetic North Pole (see Chapter 128), and problems with navigation. His compass was both very sensitive and able to cope with the ravages of a moving ship at sea, and it could be tuned to eliminate magnetic deviation caused by the use of iron in the ship’s construction. That was achieved by the placement of a small magnet close to the compass to eliminate the ship’s magnetic field.

The museum’s special Kelvin exhibition contains his original equipment and a range of hands-on experiments ideal for schoolchildren. Apart from an oddly fearsome-looking Kelvin dummy, which seems a little out of place, the exhibition does a good job of explaining Kelvin’s theoretical and practical work.

The museum also makes use of multimedia to add depth to Kelvin’s life, and offers the ability to further explore the museum’s collection of Kelvin’s equipment, and computer-based animations explaining his work.

Figure 73-3. Kelvin’s compass; courtesy of Don Turnbull (http://donturn.com)

Practical Information

The Hunterian Museum’s website is at http://www.hunterian.gla.ac.uk/. Admission is free. A useful online resource for Kelvin research is Scran (http://www.scran.ac.uk/), a fully searchable database of items held in Scottish museums—just do a search for “lord kelvin”.