Hawaii

095

Kalaupapa National Historic Park,

Molokai, HI

21° 11′ 19.01″ N, 156° 58′ 53.62″ W

21° 11′ 19.01″ N, 156° 58′ 53.62″ W

The Leper Colony

Between 1866 and 1969, people suffering from leprosy in Hawaii were forcibly removed to the leper colony on the island of Molokai. Today the leper colony is a national park and home to leprosy survivors. The colony is isolated below the highest sea cliffs in the world, with a drop of 1,010 meters. Reaching the colony entails a mule ride or hike down the cliffs following a 4.5-kilometer trail.

The trail provides a stunning view across the sea, and prior to the arrival of aircraft was the only way to reach the colony below. All supplies had to be brought in down the cliff, or on the occasional boat: to this day a large boat docks only once per year, carrying heavy items like televisions, refrigerators, or cars.

If you want to visit Kalaupapa today, taking a tour is mandatory. The small town at Kalaupapa is home to an aging population of leprosy survivors, many of whom have lived there for more than 50 years. The tour is run by a resident of Kalaupapa who survived leprosy and decided to remain.

Just seven years after the colony opened, the Norwegian scientist Gerhard Armauer Hansen isolated the bacterium responsible for leprosy: Mycobacterium leprae. It was the first bacterium shown to be responsible for a human disease. Shortly afterward, the German physician Robert Koch isolated the bacteria responsible for anthrax, tuberculosis, and cholera. The isolation of these bacteria put an end to the miasma theory of disease, which held that diseases came from breathing in air from decomposing matter.

To this day, leprosy’s exact mode of transmission is unclear, although it is suspected that close contact between infected people is the primary mechanism. It is thought that leprosy is airborne through droplets from the nose and mouth.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, governments around the world concluded that the safest way to deal with lepers was to isolate them in colonies. Isolation was partly driven by the physical disfigurement that sufferers endured, and partly because leprosy was believed to be highly contagious.

The first treatment for leprosy didn’t appear until the 1930s. The antibiotic dapsone (sometimes referred to as sulfone treatment) cured leprosy after years of treatment, but the disfiguring effects were irreversible. Many leprosy survivors decided to remain in Kalaupapa rather than attempt to reintegrate with Hawaiian society.

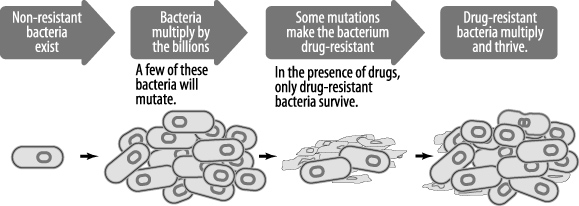

Subsequently, Mycobacterium leprae developed resistance to dapsone, and only in 1985 did effective treatment become available. To treat dapsone-resistant leprosy, three drugs are used: dapsone, rifampicin, and clofazimine. This multidrug therapy has been provided worldwide and free of charge by the World Health Organization since 1995.

In 2000, the WHO achieved its goal of bringing the prevalence of leprosy down to fewer than 1 case per 10,000 people. Nowadays, leprosy affects fewer than 1 in 50,000 people and is completely curable.

The remaining residents of Kalaupapa are elderly and the population is dwindling. Eight thousand people died on this triangle of land, and just a handful of survivors remain. The history of Kalaupapa spans a period of enlightenment in medicine, from the discovery of the bacterial cause of disease, to cures by antibiotics, to the realization that diseases could mutate and resist the cure.

The long hike down the cliff gives you plenty of time to reflect on medical scientific progress and the treatment of patients.

Practical Information

Information about visiting Kalaupapa is available from the U.S. National Park Service at http://www.nps.gov/kala/. There’s also a small museum dedicated to leprosy in Carville, Louisiana; details of the National Hansen’s Disease Museum can be found at http://www.hrsa.gov/hansens/museum/.