Chapter Three

Some days later Pete’s mum said to her husband, ‘I’m a bit worried about Pete.’

‘Why?’ asked Pete’s dad.

‘This week he’s spent every spare minute up that apple tree. He’s got all his toys and books in his bedroom, yet he’s always in that treehouse.

‘And he talks to himself up there. I heard him when I was gardening yesterday.’

‘Probably had his friend Dave with him.’

‘No. I thought that, but I could see Dave over the fence, playing in his own garden. And that’s another thing – Dave came to our door last Monday talking a lot of rubbish. And it was just the same with Pete. I heard him saying, “Nice. Nice. Who’s a good Nice?” What sense does that make?’

‘I shouldn’t worry,’ Pete’s dad said. ‘He’s just playing some game.’

‘And another thing,’ said Pete’s mum. ‘He seems to be eating so much nowadays. He’s always asking me for biscuits, and yesterday I caught him with a handful of cornflakes. When he saw me, he stuffed them in his mouth. Dry cornflakes. I ask you!’

Apart from that slip-up, Pete had managed to smuggle all sorts of food to Nice. As well as biscuits and cornflakes, he tried her with a number of other foods recommended in Mice and How to Keep Them – bread, cakecrumbs, and bits of carrot and apple and banana. He only gave her very small amounts, of course, for she was only a very small animal. But Nice ate everything he gave her and seemed, Pete thought, to be growing quite fat.

She had also grown very tame. Pete would take her out of her cage and sit in his chair, and she would climb all over him, running up his arm and on to his shoulder and tickling his neck with her whiskers.

At the end of the next week, Pete and Dave were walking back from school together. It was very windy – a southwesterly gale was forecast – and they battled along with their heads down.

‘How’s the mouse?’ shouted Dave.

‘She’s fine!’ yelled Pete.

‘Your mum and dad still haven’t found out?’

‘No! They never will!’

Later, Pete climbed the rope ladder to give Nice her supper. The wind was stronger now and the branches of the old apple tree were whipping about. The treehouse creaked a bit in the gathering storm.

Pete lay in bed that Friday night, listening to the wind howling outside. For a while he worried a little bit about Nice, in her cage in the treehouse in the apple tree, but then he fell asleep.

Because it was a Mouseday morning, he slept late and, by the time he woke, the wind had dropped. But when he looked out of his bedroom window, it was to see a terrible sight.

The apple tree had blown down in the gale!

It lay flat, its roots exposed. Amidst its broken branches was the wreckage of his treehouse.

Pete dressed and dashed downstairs.

‘Mum! Dad!’ he cried. ‘My treehouse is smashed!’

‘I know,’ his mum said. ‘I’m so sorry, Pete.’

‘Good job it happened at night, otherwise you might have been in it,’ his dad said. ‘You could have been killed.’

Like Nice has been, thought Pete miserably.

He walked across the lawn and stood by the fallen tree. The treehouse had completely collapsed.

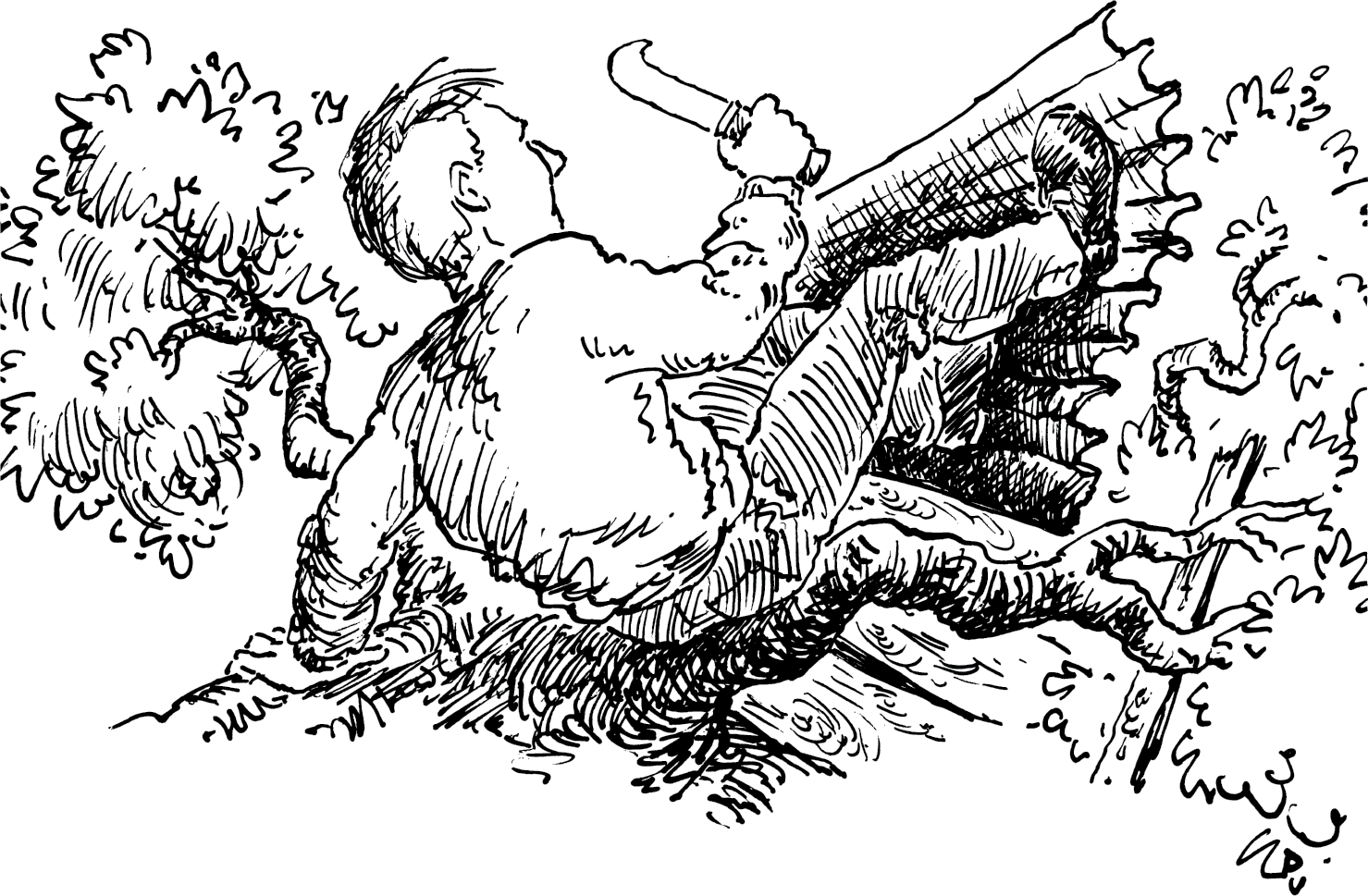

His father came to stand beside him, a billhook in his hand.

‘What did you have in there, Pete?’ he said. ‘Anything of value?’

‘Yes,’ said Pete. I don’t want to see her dead body, he thought. But I can’t just leave her there.

‘Let’s have a look,’ said his father.

He chopped away at the tangle of branches until he reached the wreck of the treehouse. He wrenched off the battered tin roof. Under it was the garden chair (smashed), Pete’s pillar box (bent but with some coins still rattling in it), Mice and How to Keep Them (a bit bedraggled, but still all in one piece) and … the mouse cage. By some miracle it seemed to be undamaged.

‘What’s this?’ Pete’s dad said.

‘My mouse cage,’ said Pete.

‘Mouse cage? But you haven’t got a mouse.’

‘I have,’ said Pete. ‘Or rather, I had. I don’t want to see her, Dad. Can you bury her for me, please?’

He turned away.

His father opened the lid of the cage.

‘Bury her?’ he said. ‘I don’t think I’d better, Pete. She seems to be as right as rain.’ He bent his head and sniffed. ‘Funny,’ he said. ‘She doesn’t smell at all.’

By the end of that Mouseday, everything had been explained and everything had been arranged.

There could be no rebuilding of the treehouse – and there was no other tree in the garden. Pete was to be allowed to keep his mouse cage on the workbench in the garage.

‘Just so long as I don’t have to come anywhere near it,’ his mother said.

‘It doesn’t smell,’ his dad said. ‘But one mouse is enough, Pete. You’re not to go buying any more mice. Promise?’

‘I promise,’ Pete said.

Last thing that Mouseday evening, Pete went to the garage to make sure that Nice was all right.

He opened the cage, expecting to see her come running downstairs for her supper, but there was no sign of her. Pete raised the lid of the little nest box.

Inside was his PEW.

But she was not alone.

With her were six blind, fat, hairless babies.

‘Nice!’ said Pete softly. ‘Oh, very nice indeed!’