Chapter Two

An Unexpected Arrival

‘You have got a lot of brains,’ said Judy.

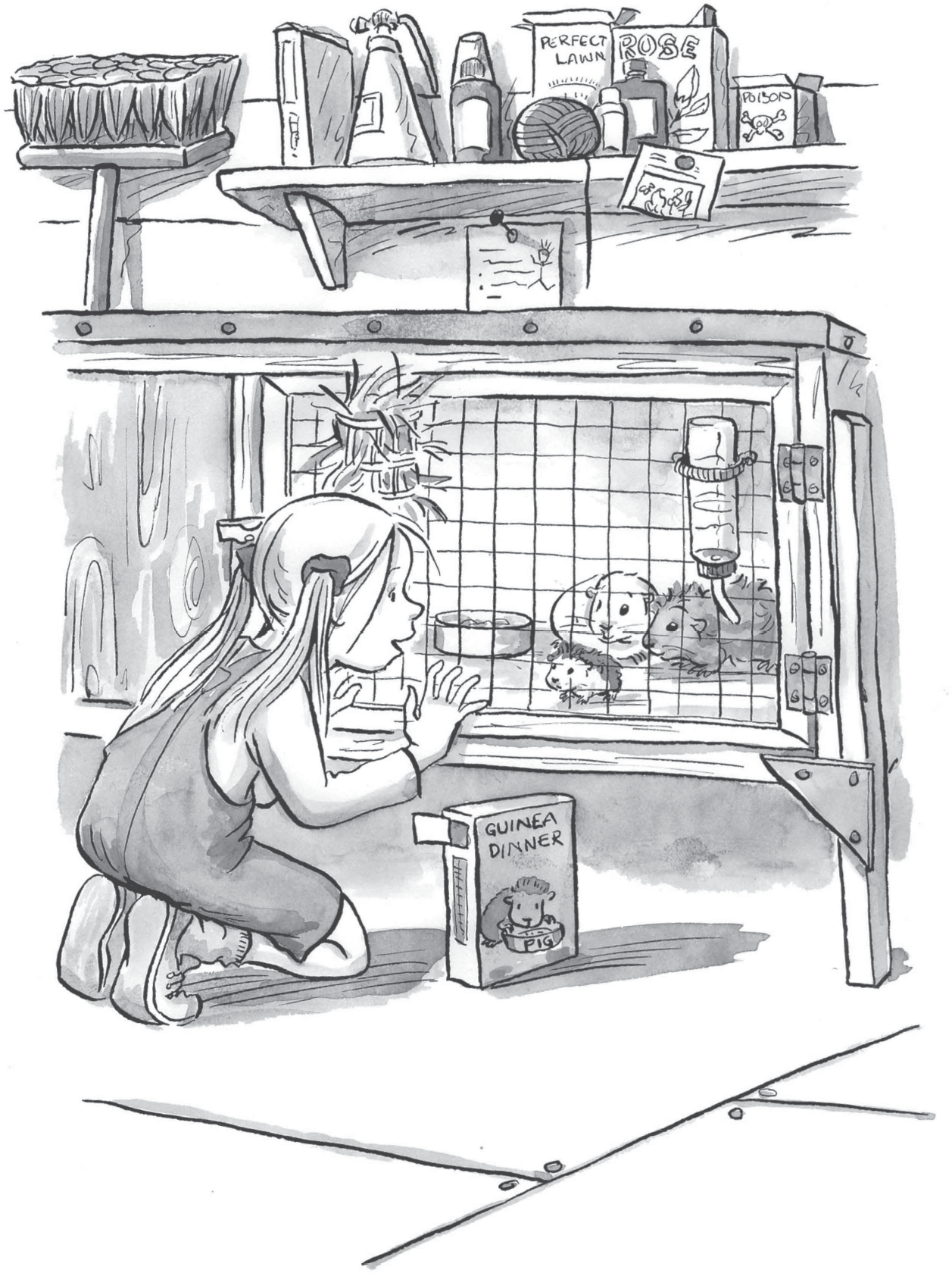

As always, she had run down to the shed at the bottom of the garden the moment she arrived home from school, to see her own two guinea pigs. One was a reddish rough-haired boar called Joe and the other was a smooth-coated white sow by the name of Molly. Judy had had them ever since her sixth birthday, nearly two years ago now, and they were very dear to her. Her only regret was that, surprisingly, they had never had babies.

‘You have got brains,’ she said, ‘I’m sure of it. It’s just that no one’s ever taught you to use them. Now, if I’d had you when you were tiny, I bet I could have taught you lots of things. If only you’d had children of your own. I’d have chosen one of them and kept it and really trained it, from a very early age. I bet I could have done.’

As usual, the guinea pigs responded to the sound of her voice by beginning a little conversation of their own. First Joe made a grumbling sort of chatter (which meant ‘Molly, you’re as lovely now as the day I first set eyes on you’), and then Molly gave a short shy squeak (which meant ‘Oh, Joe, you say the nicest things!’).

Then they both squealed long and loudly at Judy. She knew what that noise meant. They were telling her to cut the cackle and dish up the grub.

‘Greedy old things,’ she said, and she picked up the white one, Molly.

‘Molly!’ said Judy. ‘You look awfully fat. Whatever’s the matter with you?’

Molly didn’t reply. Joe grunted in a self-satisfied sort of way.

‘I’ll have to put you on a diet,’ said Judy firmly, ‘starting tomorrow.’

But next morning, when she went to feed the guinea pigs, the white one, she found, looked quite different.

‘Molly!’ said Judy. ‘You look awfully thin. Whatever’s the matter with you?’

This time they both answered, Molly with a series of small happy squeaks and Joe with a low, proud grumble, as they moved aside to show what had happened. There between them was a single, very large, baby guinea pig, the child of their old age. It was partly white and smooth like its mother and partly red and rough like its father.

To Judy’s delight it stumbled forward on feet that seemed three sizes too big, until it bumped the wire of the hutch-front with its huge head. Its eyes were very bright and seemed to shine with intelligence. Then it spoke a single word in guinea-pig language. Anyone could have told it meant ‘Hullo!’

‘Oh!’ said Judy. ‘Aren’t you beautiful!’

‘He gets it from his mother,’ chattered Joe in the background.

‘And aren’t you brainy!’

‘He takes after his dad,’ squeaked Molly.

Judy stared into the baby’s eyes.

‘You,’ she said, ‘are going to be the best-trained, most brilliant guinea pig in the whole world. And you’re going to start lessons right away. Now then. Sit!’

Of course, when you’re only a few hours old, standing can be tiring, but was that the reason why Joe and Molly’s son immediately sat down?