Chapter One

Jemima Tabb was a farmer’s daughter. She was eight years old, she had dark hair worn in a pigtail, and she particularly liked chickens, especially baby chicks.

Whenever one of her father’s hens went broody, Jemima would put a clutch of eggs under the hen – eggs that, with luck, would in twenty-one days’ time hatch out into fluffy little chicks.

Out in the orchard was a duckpond that was fed by a small stream, and not far from the edge of this pond was where Jemima chose to put her broody coop with its wire run attached. Sitting on eggs must be very boring, she thought, which is why she selected this spot.

‘Just you listen to the chuckle of the water as it falls into the pond, and the sounds of the ducks quacking and splashing about, and you’ll find the time will pass quite quickly,’ she would say to each broody hen as she settled it upon the eggs.

Three weeks after she had said all this to a hen called Gertie, eight little chicks duly hatched out.

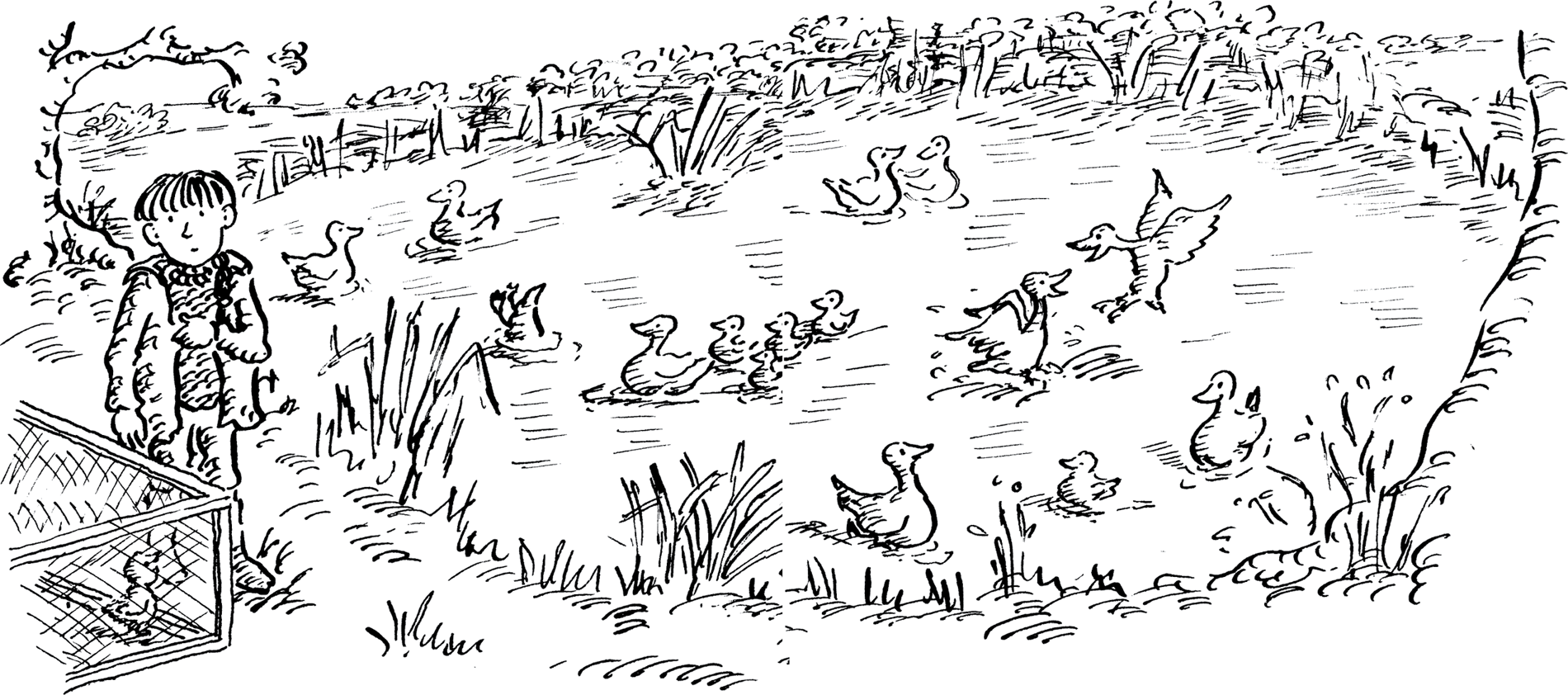

When the chicks first came out of the coop into the wire run, seven of them scuttled excitedly about on the grass, but the eighth one walked to the end of the run that was nearest to the duckpond and stood there, quite still, listening to the chuckle of the water and the sounds of the ducks quacking and splashing. From then on, he would do this every day, standing and gazing and listening, so that by the time the chicks were a month old, Gertie – the chicks’ mother – was worried and felt she needed to share her worry.

One fine morning when she and her best friend, Mildred, were scratching about together in the orchard, pecking at worms and beetles and the seeds of flowering grasses, Gertie said to Mildred, ‘You know, I think that one of my chicks is funny.’

‘Funny, Gertie?’ clucked Mildred. ‘Do you mean funny (ha! ha!) or funny (peculiar)?’

‘Peculiar,’ replied Gertie. ‘I’ve suspected it for some time now. The other seven chicks behave quite normally but this one’s different. To begin with, he keeps himself to himself. Look at him now.’

Mildred looked at Gertie’s chicks as they scuttled about in the grass, pecking at anything and everything, and she saw that there were only seven of them doing this. The eighth chick was standing at the edge of the duckpond, looking at the ducks swimming about in it.

‘Is that him?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ replied Gertie.

‘Well, he’s only looking at the ducks.’

‘Yes, I know, Mildred. But why is he looking at the ducks?’

‘Better ask him,’ said Mildred.

‘You!’ squawked Gertie at the chick. ‘Come here!’

At the sound of her voice, the eighth chick turned and came towards them. Usually little chicks run to their mother when she calls them, run very fast, flapping their stubby little wings. But this one was in no hurry.

He came slowly, looking back over his shoulder once or twice at the ducks in the pond, and when he reached the two hens he did not cheep and peep as an ordinary chick would have done. Had Gertie called any one of his brothers and sisters, they would have rushed up to her, saying, ‘Yes, Mummy?’ and probably adding politely, ‘Good morning, Auntie Mildred.’

This chick, though, simply stood there and said, ‘What?’ He did not say it in a rude way, but rather in the tone of someone who has been interrupted in the middle of something important.

‘Now,’ clucked Gertie. ‘What were you doing?’

‘Looking at the ducks,’ her eighth chick replied.

‘Yes, but why were you looking at the ducks?’

‘I like ducks,’ he said. ‘They’re cleverer than you are, Mum.’

‘Cleverer?’ squawked Gertie. ‘Whatever d’you mean, boy? Compared to hens, ducks are stupid. They can’t run about in the grass like we can. They can only waddle.’

‘Yes,’ said the chick, ‘but they can swim. I wish I could. It looks nice.’

‘Don’t be silly, dear,’ his mother said. ‘Chickens can’t swim. Run along now.’

This time he did run, straight back to the duckpond, and stood once more at the edge.

Gertie shook her head in amazement. ‘I told you, Mildred,’ she said. ‘That chick is funny.’