Chapter Two

Gertie and Mildred moved away down the orchard, shaking their heads in a bewildered fashion. On the pond the ducks dabbled happily, while Gertie’s eighth little chick watched, wishing and wishing that he could dabble too.

What fun it looked to be playing about in all that lovely water that sparkled in the summer sunshine!

How much they were enjoying ducking their heads under, and letting the glistening stuff slide down their backs, and flapping their wings to spatter themselves with dancing drops, and wagging their rumps with pleasure!

Lucky ducks, he thought. He moved forward a step or two into the shallows at the edge of the pond. How cool the water felt!

Just then a brood of little yellow ducklings came swimming past.

‘Excuse me!’ the chick called. ‘Can I ask you something?’

The fleet of ducklings turned as one, and paddled towards him. ‘Ask away, chick,’ they cried.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘how did you all learn to swim?’

‘Learn?’ they cried, and they gave a chorus of shrill squeaks that sounded like laughter.

‘We didn’t learn,’ one said.

‘We didn’t have to.’

‘We just did it.’

‘Naturally.’

‘Like ducklings do.’

‘Well,’ said the chick, ‘the thing is – I want to learn to swim.’

‘Tough luck, chick,’ they said.

‘Chickens can’t swim,’ one added.

‘Your feathers aren’t waterproof.’

‘And your feet aren’t webbed.’

‘So, forget it, chick.’

‘But I can’t forget it,’ said the chick and, in his eagerness to do as the ducklings did, he took another couple of steps forward till the water was up to his knee joints. ‘Don’t go!’ he called to his new friends. ‘Just tell me, what do I do next?’

And with one voice, they called back one word. ‘Drown!’ And they paddled away making their laughing noises.

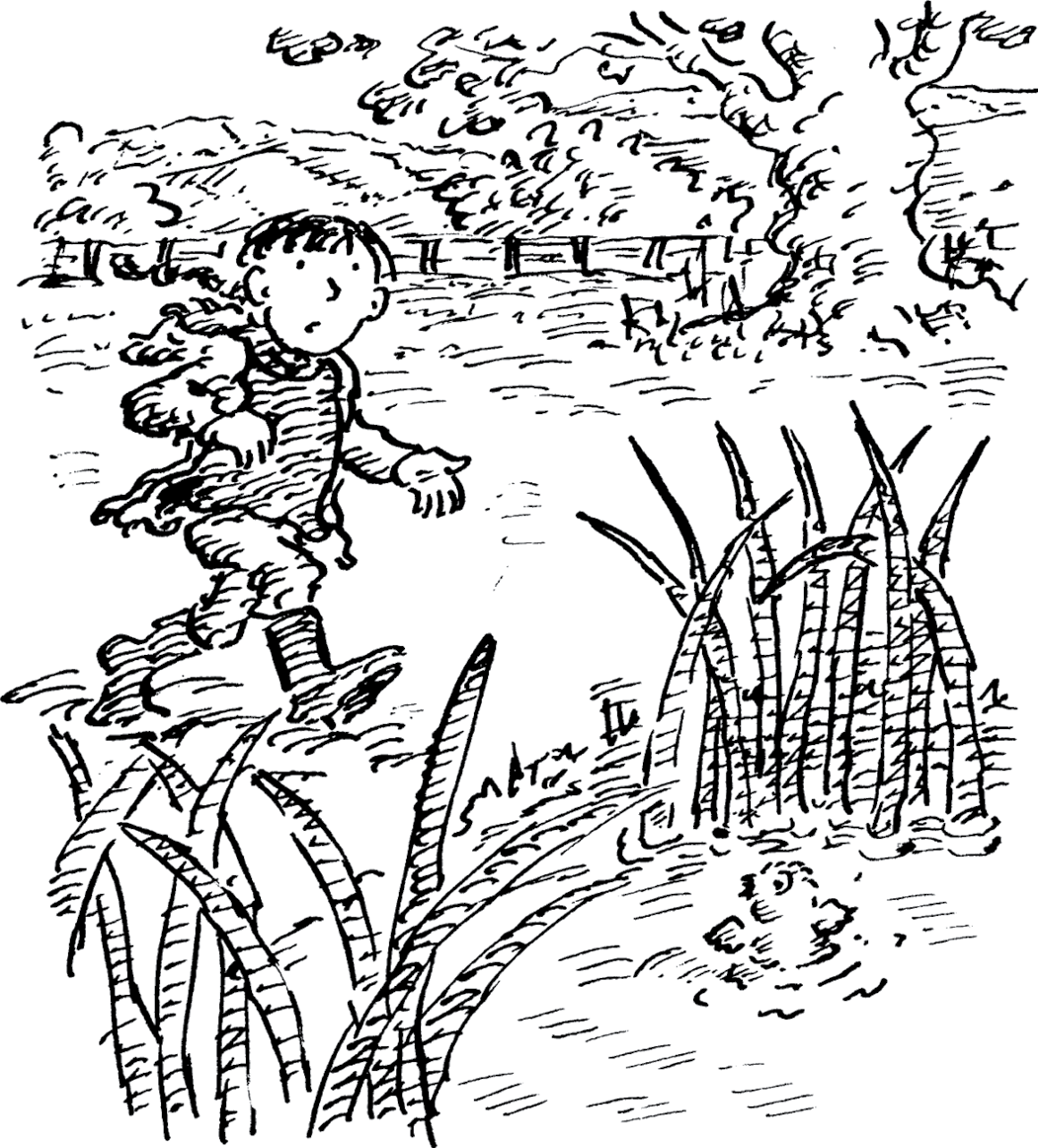

The chick took another couple of steps until he felt the water against his breast, and very cold it felt too. At that moment he heard the noise of pounding footsteps, and turned to see Jemima – the farmer’s daughter – running towards him. Then hands grasped him and scooped him up.

‘You silly boy!’ said a voice in his ear. ‘Whatever d’you think you’re doing? Anyone would suppose you were trying to swim. Chickens can’t, you know. Waterproof feathers and webbed feet – that’s what you need for swimming.’

Jemima carried the chick into the kitchen of the farmhouse and was drying his wet bits when her mother came in.

‘What have you got there, Jemima?’ she asked.

‘One of those eight chicks that are out in the orchard, Mum. He was wading into the duckpond, silly boy. Perhaps he thinks he’s a duck. I told him, chickens aren’t cut out for swimming.’

‘And what did he say?’

‘He made a funny noise, almost as though he was angry at being picked up.’ She held the chick out before her face. ‘Didn’t you, Frank?’

‘Frank? Is that what you are going to call him?’ her mother asked.

‘Well, that was what the funny noise sounded like. “Frank! Frank!” he squawked. I can’t put him back in the orchard, Mum, he’ll drown himself, I’m sure he will – won’t you, funny Frank?’

‘Where are you going to keep him then?’

‘I’ll put him in that big empty rabbit hutch till I decide what to do. I’ll ask Uncle Ted – he might know.’

Uncle Ted was Jemima’s father’s brother. He was a vet, which was very useful whenever Jemima’s father had a sick animal.

Jemima rang her uncle at his surgery.

‘Uncle Ted,’ she said. ‘It’s Jemima. I want to ask you about something. Are you coming anywhere near us today?’

‘Yes,’ said Ted Tabb, ‘as a matter of fact I am. My last call is only a couple of miles from you. I’ll look in if you like. About teatime. Just in case your mum has got any of those fruit scones about.’

‘What’s the trouble, Jemima?’

‘I’ve got a chicken that wants to be a duck!’