Chapter Five

The Disaster Years Part II

More Captures of Clean-Cut Young Canadian Seamen

The men of Rum Row are principally tugboat men and fishermen who formerly worked in the inland waters about Vancouver. They come south for a year or more at a time, some of them work on the base ships anchored off the coast, and others to handle the fast ex-submarine chasers that carry the liquor to points off the United States where small speedboats come out and unload them. Most of these jobs are entirely within the law—in fact, all of them are except those on the few boats which “run in”—that is, go into American waters to unload. This is very dangerous, for the speedboat operators ashore resent having their lucrative jobs taken away. They revenge themselves by helping the revenue men capture such boats.

Three months after the capture of Quadra and seizure of Prince Albert, another mother ship, the three-masted auxiliary schooner Speedway, met disaster after departing Victoria on January 23, 1925, loaded down with some 17,500 to 18,000 cases of liquor. While her official paperwork stated that the liquor-laden schooner was bound for Champerico, Guatemala, her master, of course, never intended to sail her that far. Instead, a false landing receipt would be written up for the vessel at Champerico, probably around the same time the mother ship was delivering up her cargo far out at sea somewhere off the US coast, or perhaps even before she had left Canadian waters. Hugh Garling noted in one of his Harbour & Shipping magazine articles that Speedway, which was 155 feet in length, was loaded with a particularly dangerous cargo. Along with the liquor in her holds, she was carrying the equivalent of eighteen thousand cases of distillate (the purest of grain alcohol) in five thousand-gallon tanks below decks and sixty-five drums stowed on deck and in the after-hold. Also, Speedway’s auxiliary power happened to be a 250-horsepower gasoline—not diesel—engine. Therefore, apart from the presence of the distillate, her fuel tanks were filled with particularly volatile fuel.

The Daily Colonist reported on January 28, 1925, that a Mr. F. M. Bonner of Howe Street, Vancouver, had bought the famous motion picture schooner Pirate at an auction sale in Vancouver and changed her to Canadian registry under the name Speedway. It was also alleged that Mr. Bonner sold the Speedway to a private liquor export concern and the vessel was chartered to Seattle-based Roy Olmstead’s Western Freighters, to deliver an order of liquor to Champerico. After casting off from Victoria, Speedway cleared Cape Flattery, dropped the towline, and was making good time in the open Pacific with all sail set the following day. (Because of Juan de Fuca Strait’s confined waters, large sailing vessels required tugs to tow them in and out of the strait.) Then at three thirty that afternoon, Second Engineer Matthews raised the alarm by shouting, “Fire!! Fire!!” Captain Robert Sinclair rushed down into the engine room with his engineer to discover that the single fire extinguisher was nearly dry of chemical and that the fire pumps couldn’t be started. With no means to contain the conflagration, flames were soon racing out of control along deck beams and the deckhead. (The official wreck report stated that the fire was “caused by spontaneous combustion following explosion of gases, in the region of the Standard Exhaust.” In other words, the engine backfired.)

Fearing that the flames would soon reach the fuel tanks near the engine room—or even the five thousand gallons of distillate—Captain Sinclair ordered all hands to the boats and abandoned ship. Once two boats were away, they were dismayed to discover that they weren’t provisioned with water and decided to return to the ship to secure some, regardless of the risk. The crew was required to wend their way across the water carefully since oil was burning across its surface some fifty feet all around the schooner. By the time they were able to board their ravaged vessel, the fire had burst through the engine room, the cabin was already gone and the masts and sails were immersed in flames.

As they pulled away from Speedway around five o’clock that afternoon, there was a thunderous explosion as the distillate tanks blew up, shattering the deck into matchwood and sending steel drums of distillate and cases of whisky flying above the masts 250 to 500 feet in the air. Among the shrapnel falling from the sky was a piece of metal that drove through the bottom of First Mate Metcalfe’s boat, causing a good deal of panic before the hole was plugged. After standing off to watch their blazing ship sink beneath the waves, they set sail in a north-easterly direction for the American coast. Vancouver’s Harbour & Shipping magazine reported in February 1925 that Speedway sank about sixty-five miles west of Grays Harbor, Washington.

Captain Sinclair’s boat, with six men aboard, wasn’t in the water long before it started leaking. Its occupants were preoccupied with bailing as the wind picked up and, by that evening, a heavy sea was running. Early the next morning the Matson Lines steamer Manulani was sighted inbound from Honolulu for Seattle. It was good timing since by this time, Sinclair’s boat was half full of water that continued to rise regardless of the crew’s non-stop bailing. Once they were rescued, the liner dropped them off at the American lightship Swiftsure at the entrance to Juan de Fuca Strait. The other boat, with First Mate Metcalfe in charge, was able to safely make its way to Pachena Bay under sail and oar, but what with the heavy seas running that night, the rudder was carried away. Fortunately, despite his exhaustion, Metcalfe was able to jury-rig a rudder, which allowed him to navigate their boat towards land through the rocks and pinnacles strewn along the Vancouver Island shoreline.

The day before all the survivors were to arrive into Victoria harbour aboard the Canadian Pacific Railway steamer Princess Maquinna, The Daily Colonist ran a large headline across its front page: “Allege Doomed Vessel Hijacked.” According to the sensational story, Seattle sources reported that Speedway’s liquor cargo had already appeared on the city’s “outlaw” whisky market. According to the article, this led to two possible conclusions: either the schooner was hijacked before she sank, or a duplicate shipment of identical liquor (Scotch whisky), “a brand so seldom seen as to be almost unique in this locality has been landed under cover.” Of course, once captain and crew stepped ashore in Victoria, the hijacking theory was dismissed.

It was only a week and half later when another disaster at sea involving a Canadian rum runner occurred. This time it involved a Canadian mother ship that went to the rescue of an American vessel in distress. On February 1, 1925, in the midst of one of the worst storms that winter, the 579-ton steam schooner Caoba, which was twenty miles south of Tillamook Rock, Oregon, discovered her rudder shaft had cracked. Meanwhile, her seams were opening up from the terrible pounding the vessel was taking and she was rapidly filling with water as the engine room pumps were unable to keep up. To make matters worse, she was at the mercy of wind and wave, having lost steerage. Finally, Captain Wilfred Sandvig ordered his crew of eighteen into the schooner’s two boats. They remained adrift for two days before the boat with First Officer A. Rigaula and eight crewmembers in it was picked up by the steam schooner Anne Hanify, which passed them over to the Grays Harbor–based tug Cudahy to take them into Aberdeen. The other boat, with nine aboard and under the command of Captain Sandvig, was picked up a few hours later off the Willapa Bar by Pescawha.

Of Canadian registry, the two-masted 90-foot auxiliary schooner Pescawha was built in Liverpool, Nova Scotia, in 1906. Sometime shortly after, she arrived on the West Coast to join the pelagic seal hunting fleet working out of Victoria, but her career in the trade didn’t last long. After the fur seal population was nearly hunted to extinction, the United States, Great Britain (representing Canadian interests), Japan and Russia signed the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention on July 7, 1911. It provided for the preservation and protection of fur seals, and all open-water fur seal hunting was outlawed north of the thirtieth parallel. This development had both Canadian and American owners of sealing schooners looking for other endeavours in order to keep their boats working. The perfect opportunity presented itself when the Volstead Act came into effect in 1920. By 1923, Pescawha was chartered to Roy Olmstead’s Western Freighters and was carrying 1,052 cases of liquor in her holds. The schooner was officially registered in Canada to a James McKinley in Vancouver, who was probably one of Olmstead’s Canadian agents that he’d set up across the line in order to facilitate his liquor-importing ventures.

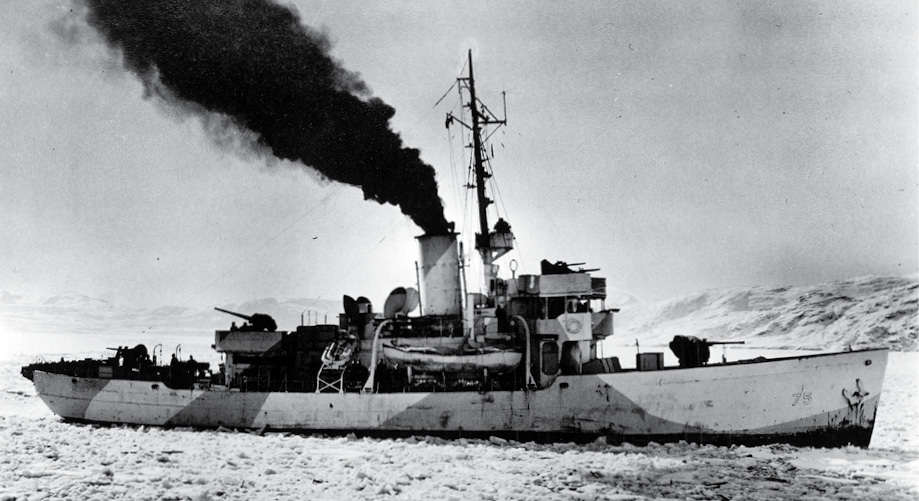

As a mother ship, Pescawha was bound for a position off the Columbia River bar when they sighted Caoba’s lifeboat and went to the rescue. While retired rum runner Hugh Garling claimed that they were outside United States waters at the time, fellow rum runner and author Fraser Miles argued otherwise. He said Pescawha was only six miles off the Washington coast at noon on February 3 when they picked up the survivors and that her captain, Robert Pamphlet, made a grievous error in judgment by not moving his boat farther offshore right away following the rescue. As a consequence, they were still well within American waters when the United States Coast Guard cutter Algonquin, which was based out of Astoria, Oregon, the port town at the mouth of the Columbia River, appeared on the scene four hours later. Algonquin (WPG-75) was 205 feet, 6 inches in length and armed with three four-inch guns, sixteen three-hundred-pound depth charges, four Colt machine guns, two Lewis machine guns, eighteen Colt .45 pistols and fifteen Springfield rifles.

The schooner Pescawha, with a number of Coast Guard men aboard, steaming up the Columbia River following her capture. Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, #154.1958.506.1.

Once Captain Pamphlet heaved to in order to transfer the rescued crew across to Algonquin, a lieutenant from the cutter was sent over and heartily commended the rum runner’s officers and crew for their quick action. A headline that appeared in the February 6, 1925, Daily Colonist summed up what happened next: “Cutter Algonquin Plays Mean Trick on Liquor Carrier” and “Shipping Men Are Up in Arms Over Method Used to Capture Pescawha – Schooner Could Have Stood Well Out to Sea Had She Not Sought to Rescue Part of Caoba’s Crew.” The situation took a turn for the worse once the lieutenant asked Captain Pamphlet for the ship’s papers. When Pamphlet objected, he and his five-man crew were put under arrest while a towline was brought over from Algonquin and Pescawha was towed into Astoria.

WPG-75 was rated as a cruising cutter, first class, by the us Coast Guard. Here she is on patrol in either the North Pacific or the Bering Sea. Once Prohibition came down, she was reassigned to Astoria, Oregon. us National Archives photo, no. 26-G-05-05-44(11).

Here, on February 5, 1925, Captain Pamphlet and his crew were brought before United States Commissioner H. K. Zimmerman, who set bail at four thousand dollars for Captain Pamphlet and one thousand dollars for each of his crew, while waiving a preliminary hearing on charges following the seizure of Pescawha as a rum runner. Captain Pamphlet responded that he was able to raise bail for himself and his crew, but that he required a few days to do it. At his request, they were all taken to Portland. The Colonist went on to say that the slightly more than one thousand dollars’ worth of whisky in the Pescawha’s cargo that had been removed to Algonquin was returned to the schooner, where it was sealed up in the hold.

Three weeks later, the Portland Telegram broke the news, “Jury Convicts Pescawha Crew. Ten Defendants Found Guilty on All Counts after Deliberation.” (Besides Pamphlet and his five-man crew, the four other defendants were the land-based agents of the operation: Jacob Woitte, Frank M. Raick, Joseph Essex and Tex Smith. These four were up for a number of charges of contravening federal law, the most serious being conspiracy to violate the Tariff Act and the liquor statute.) Captain Pamphlet wasn’t impressed with the decision. He couldn’t understand why his men were being charged, since they were only acting under orders. He pressed his point by arguing that whether it was a conspiracy to sell Jake Woitte a cargo of whisky or to take washing machines to the Fiji Islands, neither the cook nor the engineer had any say in what they were loading and where it was to be unloaded. Further, “all the men are married, have homes up in Vancouver, and have always been hard working citizens. Most of ’em are veterans of the World War. It’s going to be damn hard on them to be locked up for obeying their orders.”

It was hoped that the sentencing of Captain Pamphlet and the five crewmembers would be taken up with the British ambassador in Washington and an effort made to get a presidential pardon and a thank you for having rescued all those aboard Caoba. While nothing came of this, the citizens of Portland did present Captain Pamphlet—who they had come to hold in high regard—with a gold watch in recognition of his life-saving deed. Still, both captain and his crew were sent to prison upon sentencing. After Captain Pamphlet served out his two-year sentence at McNeil Island federal prison, he returned to Vancouver where he was to pass away two years later.

Fortune also didn’t favour his last command, Pescawha, after her confiscation by the American government. Outbound on a whaling voyage under her new American owner on February 24, 1933, and crossing the Columbia River bar, she was caught in a bad sou’wester, broke down and was driven onto the north jetty at the mouth of the river, where she was demolished. Philip Metcalfe claimed that the libelling of Prince Albert by the Commercial Pacific Cable Company and the capture of Pescawha all but ended Western Freighters, driving company director Roy Olmstead one step closer to bankruptcy by early 1925. Of course, the loss of Speedway while under charter to Western Freighters at the time didn’t help matters.

Two weeks following the seizure of Pescawha, another sensational capture took place. This time it was of the three-masted auxiliary schooner Coal Harbour, with a large cargo of liquor ostensibly destined for South American ports. She was seized near Bolinas Bay, California, about fifteen miles up the coast from San Francisco, by the US Coast Guard cutter Cahokia. At the time of her seizure, she was owned by Archie MacGillis’s Canadian-Mexican Shipping Company (which also owned the Quadra and the Malahat), but was under charter to Consolidated Exporters, which owned the cargo. Coal Harbour was 127 feet, 4 inches in length and launched in July 1881 as the lumber schooner Lottie Carson from the Hall Brothers shipyard in Port Blakely, Washington.

The San Francisco Chronicle claimed that according to waterfront reports, the “Canada Liquor Boat” was nabbed within the twelve-mile limit when she approached Tomales Bay (about twenty miles north of Bolinas Bay) to unload to the small boats of the “mosquito fleet.” The big steel tug Cahokia was 158 feet in length and like Shawnee (the Coast Guard cutter that seized the Quadra off San Francisco in October 1924), had a cruising speed of only ten knots and top speed of twelve knots. She was usually based at Eureka, California, eighty miles south of the Oregon line, but was sometimes stationed at San Francisco.

Apparently, Coal Harbour or “Gray Phantom” had been standing forty miles outside the Golden Gate for three days after filling her holds with booze in Vancouver on February 4 and, according to the Chronicle, the cutter had been keeping a close watch on the schooner as she skirted the ‘danger zone’ watching for a chance to slip in and transfer her cargo.”

Commander Malcolm F. Willoughby USCGR(T), who wrote the book Rum War at Sea back in the early 1960s, claimed that the Coast Guard’s seizure of the rum runner Coal Harbour was one of the most important in Pacific waters. San Francisco Maritime National Historial Park: B05.19,408 pl (SAFR 21374)

On the night of February 17, while Coal Harbour was attempting to unload some of her cargo southwest of the Farallon Islands, Cahokia moved in and captured the vessel and arrested its fourteen-member crew. The Coast Guard stated that the rum runner was seized following an hour’s chase and claimed that the fugitive vessel even tried to ram them in order to get away.

Once Coal Harbour was boarded and the cargo checked, a preliminary estimate by US customs officials suggested there were some ten thousand cases of whisky aboard, which were valued at market prices at more than six hundred thousand dollars, all consigned to John Douglas & Company, based in La Libertad, El Salvador. Two days following this sensational seizure, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that, “Whisky consequently shot up ten dollars a case f.o.b. in San Francisco Bay” and that “government officials were elated. They believed last night that they have dealt a death blow to the biggest and oldest of the Canadian smuggling companies—Consolidated Exporters, Ltd. The news caused panic in the bootleg market.” Chief Warrant Officer Sigvard B. Johnson, in command of Cahokia, also pointed out that there had been a sizeable rum running fleet off their coast just outside the danger zone at the time of the capture. He said that during the chase, two vessels, one a large ship capable of twenty knots, appeared at close range, surveyed the action with their searchlights and then disappeared quickly. Once the Coast Guard had Coal Harbour under tow, they were jeered and threatened by the crew of Malahat, which the cutter had actually been searching for when it seized Coal Harbour. Malahat was watching the proceedings and steamed within hailing distance while someone aboard grabbed a megaphone to shout across to Cahokia, “She was beyond the twelve-mile limit … You have no right to take her! You’re stirring up a row!” (It is likely that the Malahat avoided capture because a single Coast Guard ship was only capable of dealing with one mother ship at time.)

Captain J. M. Moore, commander of the local Coast Guard district, denied the story going around that Coal Harbour resisted seizure and the crew even attempted to scuttle their ship. (Coal Harbour was found leaking badly in the harbour, what with her being an old wood sealing schooner.) He said that the rum ship’s crew had simply refused to catch a towline tossed to them from Cahokia, which required Chief Officer C. E. Kipste and three men to run alongside her with a boat and climb aboard to secure it. While Cahokia was towing Coal Harbour through the Golden Gate, “a swarm of little fishing craft, supposedly headed for the Farallones to unload the rum ship, met them just inside the heads.” Government officials were elated with their latest capture. The Chronicle article concluded with Collector of Customs W. B. Hamilton stating that “If we haven’t gone so far as to break the rum runners’ backs, we have at least dealt them about the heaviest blows they can suffer.” And once the mother ship’s officers and crew were ashore in San Francisco, booked in the city prison and with one hundred thousand dollars in bail posted, Kenneth Gillis, assistant US district attorney, informed the press that a charge of violation of the Prohibition Act would be filed against them all. A reporter with the San Francisco Chronicle who happened to be on hand when Coal Harbour arrived into San Francisco seemed somewhat surprised to discover that “the crew of the Coal Harbour were clean-cut young Canadian seamen, far above the average type of former captured crews.”

The Coal Harbour was commanded by Captain Charles Hudson, “a grizzled British skipper of 60 years” while his brother, E. W. Hudson, was signed on as supercargo. The ship’s complement also included First Mate Eric Best, Second Mate H. Whitmore, Chief Engineer Robert Bell and Second Engineer Frank Gerdy, along with six deckhands, the cook and the mess boy. Bail for the officers was set at ten thousand dollars while those of lesser rank were required to post five thousand dollars. As for the ship’s cargo, much of it was piled on her decks in sacks, “ready for quick unloading.” Also, it was discovered that most of them contained strips of cork. It was assumed that this was done so that the mother ship could toss the sacks over the bulwarks for her customers to pick up in the event that there were high seas and they couldn’t run alongside.

According to the Chronicle, “The rum-runners asserted that liquor ship Strathcona [Stadacona] stood off the coast for weeks, supplying small boats unmolested.” The 168-foot Stadacona was originally launched as the steam yacht Columbia II in Philadelphia in 1898 and later served with the Canadian Navy in World War I as HMCS Stadacona. In 1924 she was owned by Central America Shipping Company of Vancouver but there are no records of what work she did. That same year, the Stadacona passed into the hands of Ocean Salvage Company, which was owned (at least on paper) by Joseph W. Hobbs, who converted her into a mother ship. However, it is likely that Ocean Salvage was one of Roy Olmstead’s two Canadian liquor export outfits, the second being Western Freighters, for which Hobbs was a Canadian agent. Since the company was nominally owned by Hobbs, however, the vessel kept her Canadian registry.

A few days later, the Chronicle also claimed that “the rum-chasers [Coast Guard] have followed the Prince Albert [owned by Olmstead] around in circles, but have never taken her” while she was sitting out on Rum Row. The paper went on to say that they couldn’t get the “self-appointed investigators” (the crew of Coal Harbour) to make a statement as to their intentions upon arrival into the city. The paper believed that the Canadian operators probably “suspect ‘double-crossing’ and are prepared to expose inner workings of the liquor traffic to get even.” Ships and crew working for Consolidated Exporters saw Olmstead’s Western Freighters as rivals and figured the company was trying to knock them out of the San Francisco market, especially since investors from the city held an interest in Western Freighters.

It wasn’t until December, ten months later, that the Chronicle reported that Collector of Customs William B. Hamilton directed a crew of men, under heavy surveillance by customs officers, United States deputy marshals and special agents of the Internal Revenue Bureau, to unload the 9,963 cases of various brands of Canadian and Scotch whisky from the captured boat. “The vessel had lain under seizure off Goat Island [today’s Yerba Buena Island] and the collector has been kept in a state of constant apprehension lest rum pirates seize the Coal Harbour’s cargo.” Once unloaded at Pier 19 down along the Embarcadero waterfront, the schooner was to be towed over to Government Island in the Oakland estuary “to keep company with another captured rum runner, the Quadra.” And when an unofficial recheck was made of her liquor cargo, around a thousand more cases of fancy imported liquor were found aboard than were listed in her manifest. Deputy Collector of Customs John Toland noted that, the entire cargo was of the finest “stuff,” representing twenty-five brands of Scotch and other fine liquors. “There is no question, he declared, but that the whisky has come from Europe and that its owners have evaded duty in Canada in addition to violating the Prohibition laws of this country.” It was speculated that this extra stock, estimated to be worth around forty thousand dollars, may have been taken on from another rum runner off the California coast and that perhaps Captain Hudson was planning to do a little trading on his own. Meanwhile, as the Coal Harbour was being unloaded ten months after her capture, Captain Hudson and his crew were still awaiting trial and Consolidated Exporters were looking at the possible loss of both vessel and cargo for violating the United States’ internal revenue laws.

This elegant clipper-bowed yacht was originally owned by a New York executive of the Singer Sewing Machine Company. In 1915, she was sold off and commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy as HMCS Stadacona, a depot ship. In 1919, she was transferred to the West Coast and, in 1920, she was paid off to the Minister of Marine and Fisheries as a fisheries protection vessel. Finally, following her career as a mother ship, she was sold in 1928 and went back to being a luxury yacht, the Lady Stimson, and when she was sold again, the Moonlight Maid. Leonard McCann Archives, LM2018.999.036, Vancouver Maritime Museum.

Coal Harbour being unloaded of its valuable cargo in San Francisco harbour on December 9, 1925. Coal Harbour, December 9, 1925, MOR-0768, in Ships folder, Box PxS22, San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

In a 1967–68 taped interview, Captain Charles H. Hudson recounted to Ron Burton how it was he ended up in command of the mother ship. One day, after he had made a few short trips running rum boats down at the foot of Denman Street in Vancouver’s Coal Harbour, he noticed another vessel loading liquor and offered to help. The next day, the boss, Archie MacGillis, phoned to ask why he hadn’t bothered to come down and pick up his day’s pay. Hudson replied that he just wanted to prove himself. MacGillis consequently offered him the job of running Coal Harbour. When he asked how much the pay was, and was informed four hundred a month, he promptly responded, “but if I’m going down to San Francisco for a month it’s worth six hundred dollars a month!” His demand was accepted and for the next two years he was kept occupied sailing the schooner, loaded down with over ten thousand cases of liquor, down the coast to sit off the Farallon Islands and wait for American boats to come alongside to pick up their orders. Everything was going along fine until Cahokia ran alongside them, banging on their hull, demanding to come aboard.

Captain Hudson noted that he had “an awful lot of fun with it,” running liquor down the coast with Coal Harbour. He said that they “loaded booze in Vancouver and the boat was so loaded with booze, engine room loaded with booze, house for windlass … so loaded, six or seven cases high on foredeck.” While having a ship filled to the gunnels with liquor would appear to be too much of a temptation for the crew, Hudson spoke to that issue arising on board in his interview. “First trip found crew sneakin’ booze, so after that first trip when we got back, fired most of them and employed my own men and from then on never had one scrap of trouble … I’d put a bottle out on the messroom table after supper, ‘there’s a bottle of rum there,’ and they could come in and have a hot rum. That was the only drinking they did, in three years with the boat they never touched it … it was extraordinary that you could get your men so you could trust them.”

Once Cahokia’s towline was on Coal Harbour and she was taken into San Francisco, Hudson said they only had to spend one night in jail and were let out on bail for twelve months. “It was sheer heaven, crew all staying in a nice hotel on Market Street!” Still, there was the downside to the adventure for him and his brother. “What’s mother going to say to this? Two Hudsons in jail a night … then out on bail for a year!” As soon as they were set free, and before leaving for home, he snuck back down to the ship and retrieved the logbook that had his entry indicating they were twenty-five miles offshore when captured. When they all returned to San Francisco to fight the case, he was somewhat chagrined to have to sit and watch six lawyers “being paid dollar after dollar after dollar!”

When the trial finally resumed on February 20, 1928, the US district attorney based his case primarily on the navigational fix given by Cahokia’s commanding officer in determining the location of Coal Harbour at the time of her capture. (The San Francisco Chronicle stated that, under the present procedure, the ship was figuratively a defendant before the court, rather than the men who manned it. If the jury found that the schooner was legally seized, Captain Hudson and his crew, along with fourteen others, would be entitled to a trial to determine if they actually conspired to violate the Prohibition law.)

Apparently, when the captain of the Cahokia, Chief Boatswain Mate Johnson, asked the Naval Radio Direction Finder Station for a fix by radio, he learned that it put the schooner outside the limit, which didn’t agree with where Johnson was saying she was. Later, it was discovered that Johnson subsequently altered the log entry to show the Radio Direction Finder Station’s position as agreeing with his own, which he claimed was well within the twelve-mile, one-hour sailing limit.

Federal Judge Kerrigan told the court that evidence could be submitted based on the speed of shore boats ordinarily used to make contact with the mother ships and run the liquor into shore. This ruling was used to force the defence to prove that the steam schooner Coal Harbour was beyond the one-hour sailing distance of the fast launches coming out from the beach to rendezvous with her.

Harold Faulkner and James O’Connor, the defence attorneys, continued to press their point that the ship was so far from shore that she was immune from seizure and consequently beyond the court’s jurisdiction. In his testimony that first day, Coal Harbour’s First Mate, Eric Best, told the court that the captain of the Cahokia even yelled across the water when they closed in on Coal Harbour that day, “I don’t care how far offshore you are!” The liquor ship attorneys would argue in the jury trial in February 1928 that the seizure was made forty-five miles out and that the schooner’s log dial even showed that when under tow of Cahokia, it was twenty-three miles before she was even abreast of the Farallon light. And, finally, federal attorneys were forced to admit under questioning in court that the rough log of the cutter was missing from government offices.

Captain Hudson refuted all the nonsense that came out in the trial and his indignation comes across in his 1968 interview. “What’s the deal here? We know full well our rivals up in Vancouver paid the skipper of that cutter twenty-five thousand dollars to tow us in no matter where we were … And you know damn well because you’ve got my copy of the log and that we were twenty-six miles off when they took us in.” His lawyer asked, “So what do we do?” And Hudson’s remedy? “Give them another twenty-five thousand dollars to commit an un-perjury! … And they did, and we won our case!” Hudson was fairly certain that the US Coast Guard was ordered to bring Coal Harbour in, and probably by the same party who paid the Cahokia’s bosun a bribe, in order to create financial trouble for Consolidated Exporters. He was convinced that they hoped it would cost Consolidated Exporters millions of dollars in legal fees and then they would all “throw up their hands and stop rum-running! … From what I saw during the Coal Harbour and Quadra seizure incidents, it was proof positive that the States were alive with bribery and corruption. They were saddled with a rotten law they couldn’t enforce.”

In the chapter devoted to Captain Hudson in Personality Ships of British Columbia, Ruth Greene said that First Mate Best, who was “a delightful pipe-smoking Englishman” with an impeccable English public school accent, proved an especially valuable asset in the court case. According to Hudson, it was his first voyage rum running and, fortunately for them, he knew next to nothing about the trade. As a consequence, the prosecutors weren’t able to get much out of him other than the rather baffling remark, “Are you threatening me, Sir?” Hudson also recalled that their night in jail had its lighter moments. Best, in his impeccable English, mused through puffs of pipe smoke, “Quite an experience, Sir! What!”

On March 6, Chief Boatswain Sigvard B. Johnson, master of the Cahokia, finally admitted on the witness stand that the testimony he had previously given regarding the position of Coal Harbour was false. He stepped from the stand to immediate arrest by his superior officers on a charge of perjury and was relieved of his position as commanding officer of Base 11, which was out on Government Island in San Francisco Bay at the time. After deliberating for an hour the next day, the jury declared the seizure of the ship and arrest of the crew an illegal act. Before they retired to come up with this decision, Judge Kerrigan submitted four questions to help the jury determine their verdict. Was the Coal Harbour intending to land liquor on United States soil? If so, was she intending to land it from her own decks? If not, was she instead intending to land the liquor by shore boat or fireboat? And finally, what distance could a shore boat similar to those used in such traffic cover in one hour? Of course, the answer to the first question was “yes,” the second “no,” the third “yes,” and the fourth “ten miles.” It was the answer to the third that spelled defeat for the government’s case. As it was, the defence had argued that seizure was made forty-five miles out and twenty-three miles off the Farallones. In its March 9 issue, the San Francisco Chronicle said that they learned from the defence lawyers that this particular headline-grabbing trial was unique in American jurisprudence. “It was the first time, they say, that a jury had been called to decide the question of the court’s jurisdiction. Only questions of facts are for juries. And the primary question of fact (not law) was Coal Harbour seized within or without the legal grasp of the United States offshore?”

On June 30, 1928, Federal Judge Kerrigan signed a decree releasing the ship and its $750,000 cargo of liquor. The terms of the decree gave the owners of Coal Harbour ninety days in which to check the liquor cargo—barrels of bourbon and cases of Scotch along with a thousand cases of assorted wines, including champagne—and then remove it from American territory. This was of particular interest to the local public, since it had come out during the trial that forty or fifty cases had gone missing at the time the contraband was taken from the schooner and stored in the appraiser’s building back in February 1925. Defence Attorney Harold Faulkner replied that this liquor, which had apparently evaporated, was what might be called a “social shortage.” The government retorted that rum runners might consider it such. Faulkner responded with a hypothetical question: “What would the Coast Guard consider it since there was a somewhat similar ‘social shortage’ when the [mother ship] Federalship was brought in here a year ago.”

At the same time Judge Kerrigan was signing the release for both Coal Harbour and cargo to the owners, the Attorney General’s office also agreed to forfeit their claim on Coal Harbour’s sister ship Quadra. Two and half years earlier, after Coal Harbour’s liquor cargo was unloaded on the Embarcadero waterfront, she was taken across the Bay to join the other captured mother ship, Quadra, where both were left to sit and rot away. In its explanation of the circumstances behind Judge Kerrigan’s call for her release in June 1928, the Chronicle said, “The Coal Harbour will not immediately sail from San Francisco harbour—if she ever sails—for the long anchorage is said to have made her unseaworthy.” The final, handwritten entry in the Vancouver Ship Registry for Coal Harbour recorded that “Certificate cancelled, and Registry closed this 15th day of October 1928. Vessel sold to foreigners (USA.) Advice of HBM Consul of Los Angeles, Calif. USA.”

And as for her cargo? On July 4 of that year, the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that “the 10,000 packages of liquor from the rum runner Coal Harbour were turned back to the owner by the government yesterday and will be shipped to Antwerp, Belgium, aboard the North German Lloyd liner Witram, sailing from this port July 14.”

The H. W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest stated that, after several years of lay-up in Los Angeles, Coal Harbour, now with “a peculiar bark rig,” and under her original name, Lottie Carson, went on to appear in several motion pictures, including the 1930s movies Slave Ship and Souls at Sea, as well as South of Pago Pago, which appeared in 1940. Following the entry of the United States into World War II in December 1941, she was re-rigged as a schooner and went on to operate in the Mexican lumber trade.

If one was to believe all the press coverage of the day, it would appear that the US Coast Guard was finally gaining the upper hand with its capture and seizure of a number of rum ships throughout the disaster years of 1924 and 1925, but an article that appeared in a Los Angeles newspaper in May 1925 told a different story. It said that a huge rum fleet, carrying cargos valued at several million dollars, was lying off Southern California. The following summer it was able to report that sixteen Canadian, Belgian, Panamanian and Mexican rum runners, “the greatest mobilization of liquor-laden ships in the history of Pacific rumrunning, are hovering off San Diego.” Of course, with all the risks that it entailed, the profits from liquor smuggling were enormous. In 1925, a case out on Rum Row was worth twenty-five dollars; on the beach, forty dollars; to the retail bootlegger ashore, fifty dollars; and to the consumer, seventy dollars, or six dollars a bottle. When one considers that a 1925 dollar would be around fourteen dollars in today’s money, the financial rewards were well worth the risk.