Introduction

Don’t Never Tell Nobody Nothin’ No How

Looking back, it seems that I was destined to write about West Coast rum running. My dad, Dick James, was born in the Shetland Islands to Richard Pascoe James, a Cornish tin miner, and Ruby (née Scott). Granny’s family had made a living from the sea for generations and her grandfather and father, both named Peter, supplemented their hardscrabble existence as cod fishermen and whalers by smuggling tobacco and spirits. As it was, smuggling was never considered a crime or a sin by Shetlanders who struggled to get by on the isolated Scottish archipelago off the far end of the North Sea.

William Smith, a merchant and fish curer in the port village of Sandwick, who crewed with Ruby’s grandfather on the packet boat Rising Sun in 1891, recalled that Scott Jr. (Ruby’s father), said his father didn’t really care for strong drink and so seldom got into positions that he could not extricate himself from. At the time Scott Sr. was running Rising Sun as a “Cooper,” or smuggling vessel. They would fill the hold with tobacco and spirits at ports in Holland and Germany and then run the cargo across to the Yarmouth, Hull and Grimsby fishing fleets where they carried on a brisk trade. Prior to Rising Sun, Scott Sr. ran Martha of Geestemünde with son Peter as mate. The Scotts acquired the German boat after she was caught smuggling off the Shetland Islands coast in 1886. After they pleaded guilty, master and owner were fined twenty pounds sterling or the alternative of serving thirty days’ imprisonment, while the three-man crew was fined five pounds each or twenty days in prison. Boat and cargo were subsequently seized and the boat ended up in the hands of the Scott boys.

Four generations later, the appeal of earning a living smuggling came to the fore in my own life. After graduating from Oak Bay High School in Victoria in the mid-1960s, smoking pot and hash was a recreational activity the crowd I hung out with often indulged in. We were in our late teens and early twenties, still trying to sort out how to navigate the adult world and preoccupied with how to get by or, at least, earn a half-decent income without resigning ourselves to a boring, humdrum job around town. Some who were adventurous enough headed up island to work in the woods setting chokers or landed jobs on trollers as deckhands. But living on the south end of Vancouver Island, where it’s only a few short miles across Haro Strait into United States waters and the San Juan Islands, there was another, riskier enterprise that offered the potential of a very lucrative reward. And a few of my pals were crazy enough to try it.

It only required finding a reasonably reliable boat with a good, fast engine and making a run across Haro Strait, preferably during a dark and overcast night, to pick up an order of a few pounds of “product” on the other side of the line. Of course, it was all highly illegal but that’s how economics works: the higher the risk, especially with the selling of a banned and illegal substance, the greater the potential for an exceptional return on one’s investment. The idea seemed so very straightforward when presented by a couple of my colleagues who were always pressuring me to take part in one of their sketchy money-making schemes.

Forty years later, one old friend finally opened up and divulged his secret to success. To begin with, since my crowd was mostly from long-time Victoria families, they either kept their boats at the Oak Bay Marina or trailered them down to the Cattle Point boat launch. Then on a good dark night with no moon in the sky, they would race across into Washington state waters to Deadman Bay on San Juan Island. This particular location on the chart was Vancouver Island drug runners’ preferred spot for making a pickup. First of all, this rather quiet and isolated bay lies just outside of San Juan Island’s Lime Kiln Point State Park, and Lime Kiln Lighthouse serves as an excellent navigational aid for those running across the strait from Victoria. Also, Deadman Bay is reasonably well sheltered with a nice moderately sloped beach for pulling a small boat up on. But not only that, the island’s West Side road comes almost right down to the water in the bay. Here, their Canadian partners in the venture car or truck would arrive after picking up some pot in Oregon, so-called cheap Mexican shit selling for around seventy to seventy-five dollars a pound back in those days. After the transport vehicle arrived down at Deadman Bay, the product was discharged and loaded into the boat, which then raced off across the strait into Canadian waters. Once the weed hit the streets of Victoria, the dealers were able to sell it for a hundred and twenty dollars a pound.

Another reason why Deadman Bay worked so well was that there was little in the way of law enforcement on San Juan Island in those halcyon days of the 1960s and 1970s. As my old bud pointed out, there was virtually no US Coast Guard around in those waters, and he didn’t recall there ever being any border protection service, drug enforcement or customs agents about, especially on the Haro Strait side of the island. The only police presence there at the time was the local sheriff’s office. Even so, a number of the crowd I hung out with didn’t have the sense to know when to call it quits. While many of us got into psychedelics, some took it a little too far and not only got into coke but even proceeded into far worse intoxicants like speed (methedrine) and junk (heroin) and bore the consequences. Then there were those who got busted for possession or, worse yet, running drugs into the country, and ended up with a record or even jail time. Even though many were actually quite bright and charming individuals, once they spent time behind bars they were never quite the same.

I always wondered how these jokers thought they could continue to pull off these hare-brained schemes in the first place. It all started to make sense once I became immersed in research for this book and learned about the escapades of numerous West Coast characters who turned to rum running while Prohibition south of the border made a futile attempt to dry out the American citizenry. The Noble Experiment, as it was so aptly branded, remained in effect from 1920 through 1933 and declared illegal the manufacture, sale, importation and transportation of alcohol throughout the US and, of course, the imbibing of such products. The parallels were intriguing and the stories very similar to what was happening throughout BC’s south coast waters forty to fifty years later when local government authorities and law enforcement were attempting to put a stop to the burgeoning drug trade. Indeed, although we were unaware of it at the time, “jumpin’ the line” (the border) was the commonly used phrase back in the 1920s to describe the actions of those gutsy enough to try to make surreptitious runs across Haro Strait to the San Juan Islands or even all the way down into Puget Sound. But back then, the particularly adventurous were filling their holds and packing the decks with case upon case of good Scotch, brandy and bourbon rather than high-test weed, hashish or LSD.

Probably the most surprising revelation that occurred while researching this book was that, contrary to what most of us have been led to believe, not all smuggling during the Prohibition years was marked by violence. While the criminal element was definitely involved with smuggling and bootlegging throughout the US, where hijacking and violent shootouts were the order of the day, when it was transpiring in British Columbia waters or out in international waters off the US coast, the activity was all carried out in a very civilized and politely Canadian manner. Rather than an adrenalin-filled and dangerous undertaking dominated by hoodlums, it was, on the whole, just another export shipping enterprise working out of the ports of Vancouver and Victoria and run by a number of generally charming and professional mariners and businessmen. Still, contrary to what many of these individuals may have convinced themselves and would have us believe, there was indeed the odd shootout and even one particularly gruesome murder that occurred in the Gulf Islands on the Canadian side of the line.

Overall though, the generally decent approach Canadians took to rum running during US Prohibition was very much like what we experienced in BC back in those carefree days when my old crowd was preoccupied with importing relatively harmless soft drugs and psychedelics across the line. For instance, I personally don’t recall any of my buds packing firearms; that only came about when the consumption of the hard stuff, like meth, coke and heroin, became more widespread sometime around the mid-1970s. Another surprise was how many of the respected elderly citizens of Victoria and Oak Bay were active players involved in rum running. So I wonder if jumpin’ the line has always been part of our local Vancouver Island culture—where those who became such dedicated participants in those wild and freewheeling years of the late 1960s and early seventies had somehow been socialized to pick up where some of the older residents in our community had left off.

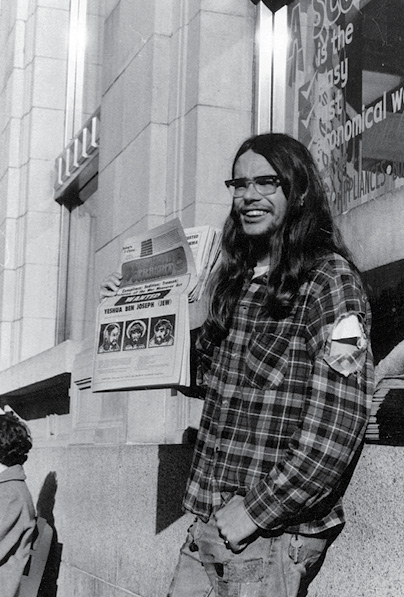

The author selling the radical Georgia Straight rag at the corner of Yates and Douglas Streets in Victoria, circa 1969. Space Pals photo, Rick “Lou Lemming” James collection.