Chapter One

Scotch Oases in a Desert of Salt Water

At the stroke of one minute past midnight, January 17, 1920, the proposed Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the National Prohibition Act, known informally as the Volstead Act, was officially declared in effect. Named for Andrew Volstead, the Republican chair of the House Judiciary Committee who managed the legislation, the act stated that from that day on, “no person shall manufacture, sell, barter, transport, export, deliver, or furnish any intoxicating liquor except as authorized by this act.” The Noble Experiment was to last fourteen years before being brought to an end in December 1933.

However, while the American government was closing tavern doors, the citizens of British Columbia chose to take a different direction that very same year. In British Columbia, a bill banning the sale of liquor, except for medicinal, scientific, sacramental and industrial purposes, was initially approved by referendum during the September 1916 provincial election, with Prohibition going into effect in September the following year. Right from the start, the attempt to prohibit the consumption of alcoholic beverages met with limited success. The legislation was not only extremely unpopular but in short order the government found it was difficult and expensive to enforce. It quickly proved a failed experiment. After only three years, a plebiscite was put to British Columbia voters (which for the first time included women) in October 1920, which read, “Which do you prefer? 1. The present Prohibition Act? 2. An act to provide for the government control and sale in sealed packages of spirituous and malt liquors?” It wasn’t any surprise when the residents of the province voted thumbs down on the existing legislation. By June the following year it was all officially over and done with, and the very unpopular legislation slipped away into the proverbial dustbin of history. Each of Canada’s nine provinces and two territories had experimented with Prohibition law but nearly all had repealed it by the late 1920s.

Still, the doors to BC’s drinking establishments weren’t exactly thrown wide open to thirsty residents looking for relief with an alcoholic beverage. Instead, what voters had approved in the referendum was a system of strict government control of the sale of alcohol with a three-man Liquor Control Board (LCB) to be set up to oversee and regulate the sale through government stores. Also, the new liquor act initially banned all public drinking unless one had a special permit issued by the LCB. This required the purchase of an annual liquor permit for five dollars and sales were limited to those twenty-one years of age and older. Additionally, BC residents weren’t able to buy liquor by the glass until beer parlours were finally opened in 1925 following an amendment to the Government Liquor Act. These establishments, with their separate men’s and ladies’ entrances, soon became popular watering holes throughout the province, where they were to retain a prominent place in BC culture as a place to relax and unwind.

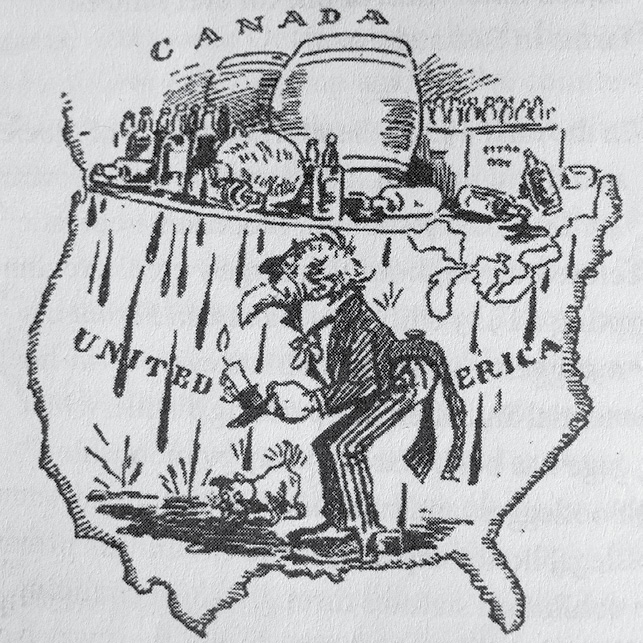

A flood of liquor from Canada across the border into the United States was already underway by 1920. While Canada’s federal government had outlawed the manufacture, transportation and sale of beverage alcohol, it could still be sold for medicinal, scientific, industrial and sacramental purposes. These provided the loopholes which bootleggers and smugglers were quick to take advantage of. “By Jing, the Old Ceiling Leaks.” Morris for the George Matthew Adams Service: The Literary Digest, 1920.

The Volstead Act was not only enacted the year British Columbia turned its back on Prohibition but also arrived in the midst of a serious postwar depression. Following the signing of the armistice in November 1918, a booming wartime economy turned stagnant and ground to a standstill. Much to the distress of soldiers returning from the Western Front, there were no jobs and they found themselves only contributing to a growing unemployment problem. As a result, many displaced workers and their families throughout British Columbia, as well as the rest of the nation, were looking for any means to get by. And some soon proved cleverer than others, especially those who happened to own anything that could float. While Prohibition had actually been in effect in the state of Washington since 1916, it was only when it was declared nationwide in 1920 that many on both sides of the border were quick to take advantage of this curious juxtaposition of Canadian and American government policies concerning alcohol. In the opinion of a large section of the public, the consumption of alcohol wasn’t really considered a crime as such, much like the recreational smoking of marijuana is viewed today. As a result, in the early years of the 1920s, bootlegging (smuggling and delivering up liquor by land) and rum running (smuggling by water) quickly developed into an extremely lucrative enterprise throughout southern British Columbia.

Once the Volstead Act went into effect, it didn’t take long before fleets of vessels, from weather-beaten old fishboats to large ocean-going steamers, began filling their holds with liquor. They would sail south from Canadian ports and sit offshore in international waters just outside the US territorial limit to deliver up their much-valued cargos to launches running out from shore. British Columbia was perfectly situated for the movement of illegal liquor by sea, particularly in local Canadian waters.

The southern tip of Vancouver Island was ideally positioned since it sticks out like a boot kicking into the exposed butt of Washington state. With a maze of islands scattered throughout the deep, sheltered waterways of the Strait of Georgia and Haro Strait, and the ports of Vancouver and Victoria only a short distance away from the American San Juan Islands, the area soon proved a veritable floating liquor marketplace where Canadian boats delivered up orders to their American counterparts in relative safely.

Still, some rum runners, especially those who custom built their own high-powered speedboats, were willing to take it a step further and reap a better monetary return by making a run under the cover of darkness to deliver up their payload into Washington state beaches. Regardless of how it was carried out, the underground trade proved extremely profitable and by 1924, it was estimated that some five million gallons of booze had been smuggled by land and sea into the US. Bootleggers and rum runners were simply taking advantage of the basic law of supply and demand.

But the scale of rum running out of Canada’s West Coast ports of Vancouver, Victoria and Prince Rupert remained relatively minor compared to that which was underway along the eastern seaboard and down in the Caribbean. While Halifax, the French islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon lying off the south coast of Newfoundland, Havana, and Nassau in the Bahamas all served as major entrepôts, some four-fifths of illegal liquor was estimated to have entered the US through the Windsor–Detroit area on the Great Lakes, according to Dave McIntosh, author of The Collectors: A History of Canadian Customs and Excise. In his detailed history of the United States Coast Guard activities during the Prohibition years, Rum War at Sea, retired commander Malcolm F. Willoughby devoted only one chapter to the liquor trade along the Pacific coast. Overall though, estimates of Canada’s share range from 60 to as much as 90 percent of the contraband market that was flooding into the US both by land and sea.

Of course, there was also a land component to the trade. Canadian vehicles often pulled right up to border crossings to transfer their loads over to American cars and trucks (often in sight of customs buildings where the officers apparently looked the other way) but the sea-based operations proved the most rewarding.

As Victoria’s Daily Colonist noted in a short article in April 1922, word had it from Bellingham-based officers of the law that “the islands are bartering grounds for ‘liquor runners’ from British Columbia and this country … The San Juan Archipelago offers an ideal field for operations.” It would appear that there were a few Canadians bold enough to venture across the line in order to garner a better return. As Washington state sheriff Al Callahan informed the reporter, “… Sucia Island [a small San Juan Island lying west of Bellingham, close to the border], the prettiest of them all, perhaps, is the clearing grounds for cargoes.” But Callahan did note that this was only of late. Heretofore, he explained, the American boats had to go into British waters to get their cargos, but now the British runners from Victoria and Vancouver were delivering up their goods on the American side and charging for their risk. (Even though most of the crew probably lived on BC’s West Coast at the time, most them were of English and Scottish background. Once the Dominion of Canada’s first transcontinental railway, the Canadian Pacific Railway, reached the nation’s Pacific coast in 1886, English and Scottish immigrants were soon flooding the province of British Columbia. Of course, the Americans were quick to identify them all as Britishers because of their accents.)

As it was, the newspaper continued, “Tales of crime often trickle in from the exchange grounds. ‘Knock overs’ are said to be frequent. Freebooters range the waters and take possession of the cargoes, not caring whether their victims are Britishers or Yankees. There is a none too friendly spirit between the rum runners.”

As it stood, Canadian rum runners were well within their rights and not breaking any laws, as long as they stayed on the Canadian side of the border where they also felt relatively safe from hijacking. Most BC boat operators who took up rum running considered themselves just ordinary businessmen who were providing a delivery service by passing over their cargos to American vessels well within Canadian waters, preferably at any number of the convenient, out-of-the-way bays and coves hidden throughout the small islands on the Canadian side of Haro Strait. These included Sidney, D’Arcy and Gooch Islands and East Point on Saturna Island. The Discovery and Chatham Islands—right across from Oak Bay’s popular Willows Beach—proved exceptionally ideal since they were only minutes away from US waters with a fast boat.

An article from the Victoria Daily Colonist, Marine & Transportation page, April 26, 1924. BC Archives newspaper microfilm files.

Philip Metcalfe explained it all well in Whispering Wires: The Tragic Tale of an American Bootlegger, his biography of Seattle bootleg kingpin Roy Olmstead. Numerous Canadian boats, some as small as 18 feet, which he claimed were capable of packing seventy-five to a hundred cases, were working for the big liquor exporters and delivering up their cargo f.o.s. (flat on the sand) to American boats out behind Discovery, Saturna or D’Arcy Islands. The trip out and back took only a few hours and an enterprising boat owner could easily make five or six trips a month and collect a profit of a thousand dollars (around fourteen thousand dollars today). In 1922, the Canadian government granted more than four hundred “deep sea” clearances to small boats engaged in the liquor trade. This fleet of fishboats, packers and tugs grew by the week and was soon recognized as the “whiskito fleet.” Even with these fabulous returns, some more adventurous types were still willing to take the chance and run their load across the line into American waters to do even better.

In April 1924, Victoria’s Daily Colonist noted that properties on a number of the islands in the busy shipping channel were in hot demand. “Mr. A. E. Craddock, of the County of Limerick, Ireland, has purchased the north end of Prevost Island” and “two other islands recently changed hands, one going to a prominent British distiller, and the other to a San Francisco capitalist, who has money invested in Pacific Coast liquor running ventures … Publicity given Smugglers’ Cove, Discovery Island [a local name] recently, has driven rum-runners to other islands in the Gulf. More than twenty of these little dots of land are credited with each being a Scotch oasis in a desert of salt water.”

One very convenient transfer point, just over four miles directly east from the village of Sidney on Vancouver Island and lying next to Gooch Island, is Rum Island, which happens to be three-quarters of a mile from the US–Canada boundary out in Haro Strait. Smugglers Nook, historically another favoured rendezvous and stash point, whether the contraband was wool from the local sheep ranches, opium or booze, was located off the southeast end of North Pender Island.

With any contraband substance, the more risk taken importing or exporting a product, the more rewarding the financial return will prove if the undertaking is pulled off successfully. The export of alcohol across the line during US Prohibition was no exception. While a quart of good Scotch only cost $3.50 in Seattle prior to Prohibition, once the Volstead Act went into effect and bootleggers were still scarce, the price soared as high as $25 a quart. By 1924, it was selling curbside from anywhere from $6 to $12 a bottle. In the early years, American rum runners were paying anywhere from $25 to $40 for a twelve-bottle case (over $300 a case in today’s currency) depending on the particular brand of Scotch, bourbon or gin delivered up by Canadian boats, which could be sold for up to $70 a case in Seattle.

The US government, of course, was annoyed when a flood of booze began pouring across the line—whether by land or sea—and put pressure on their Canadian counterparts to impose tougher laws on rum running. Still, as far as the Dominion government was concerned, it wasn’t Canada’s responsibility to enforce America’s liquor laws since the nation’s big export houses were private concerns that were licensed to ship liquor anywhere in the world. Still, on the surface, the federal government in Ottawa appeared to be somewhat willing to preserve good relations with its neighbour to the south, but it was most reluctant to forego the tax revenue generated by this particularly lucrative export trade. As far as Canadian government officials were concerned, everything was perfectly legal as long as all the customs and clearance paperwork was filled out properly. But in order to pacify their counterparts in Washington, DC, and at the same time boost government tax revenues, in the first year of the trade’s operation, Ottawa raised the fee for a liquor export licence from three thousand dollars to ten thousand dollars.

In response to the federal government placing this steep tax on all liquor export agents, and with Prohibition firmly entrenched south of the border, it didn’t take long for a number of clever liquor merchants to figure out that it might be better if they all banded together. This way the group only had to pay one ten-thousand-dollar licence fee for the whole lot of them.

As a result, Consolidated Exporters Corporation Limited came into being on August 25, 1922, with offices at 1050 Hamilton Street in downtown Vancouver. The stated object of the new company was to serve “as wholesale, import and export merchants, dealing with all classes of goods, merchandise, and wares and to buy, sell, prepare, market, handle, import, export, and deal in wines and alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages of all kinds whatsoever insofar as the law allows the same to be done.”

Among the more prominent shareholders listed among Consolidated Exporters’ twenty-eight directors in October 1923 was Samuel Bronfman, who had already made a name for himself operating hotels and liquor outlets in Canada’s prairie provinces prior to Prohibition. The Bronfman family started up their own distillery in Montreal in 1925 under the corporate banner of Distillers Corporation Limited and later acquired Joseph E. Seagram & Sons, whose Ville La Salle plant soon grew to be one of the world’s largest distilleries. Another individual who was to really benefit from joining the consortium was Henry Reifel who, along with brothers Jack and Conrad, owned Vancouver Breweries Limited. They later acquired BC Distillery up the Fraser River in New Westminster in 1924. When he was interviewed by Imbert Orchard, who taped hundreds of BC pioneers for CBC Radio in the 1960s, Vancouver lawyer Angelo Branca said that the “industry was all corralled by the Reifel company. They made millions and millions of dollars.” Although Henry Reifel was appointed one of the seventeen directors upon incorporation and also served as the secretary of Consolidated in the early years, the Reifel interests set up their own separate shipping company to handle the liquor produced by their British Columbia–based breweries and distilleries.

In order to carry on the business of wholesale and retail sales of liquor, it was noted in the Consolidated Exporters memorandum of association that they were able to “produce merchants, commission agents, manufacturers’ agents, brokers, importers, exporters, ship-owners, charterers, charterers of ships, and other vessels.” As such, this arrangement soon proved its worth, especially its sea-going arm, and by the end of the Prohibition years in late 1933, the various shareholding companies had done exceedingly well.

As Philip Metcalfe so aptly pointed out in Whispering Wires, it wasn’t long before, “like a fabulous sea monster, its head stuffed with American greenbacks, Consolidated had tentacles reaching down the coast to Mexico and Colombia, across the Isthmus of Panama to Belize and eastward all the way to the island of Cuba. In the final years of rumrunning, the company established depots in Tahiti … and China.”

Throughout the Prohibition years, a steady stream of liquor consignments arrived into Vancouver harbour from Glasgow, London and Antwerp aboard Canadian Government Merchant Marine Ltd. freighters, Harrison Direct liners and Royal Mail steam packet ships. The liquor was brought right into Ballantyne Pier in Burrard Inlet, where it was put into government security. Here the finest brands of Scotch, rye, champagne and brandy were stored in bond. (Dominion Bureau of Statistics figures revealed that between 1925 and 1929 the value of all liquor imports into Canada grew from $19,123,627 to $48,844,111.) From this bonded warehouse, case upon case of liquor was loaded quite openly aboard “mother ships,” the steamships or big ocean-going lumber schooners that sailed south to sit off the US coast in international waters out on “Rum Row.” All that was required of the owners of the cargo was that they post a bond and swear on the vessel’s clearance papers that it was destined for a Mexican, Central or South American port.

Stephen Schneider, associate professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminology at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, pointed out in Iced: The Story of Organized Crime in Canada that the underground liquor trade was driven by the most basic of economic laws: that of supply and demand. He also notes that “the Canadian conglomerates that grew fat off Prohibition were some of the first corporations to be vertically integrated, handling all aspects of their trade including production, distribution, sales, export, financing and marketing. They were also the most corrupt, unethical, and duplicitous corporations to ever operate in this country … and did not shy away from selling to dangerous criminal syndicates … They forged export documents, fraudulently listed the consigned destination of exported liquor as anywhere but the US, used counterfeit landing certificates from foreign ports, set up shell front companies, misrepresented the contents of their products, forged liquor labels, and bribed customs officials.” As explained by Captain Charles H. Hudson, a decorated World War I Royal Navy veteran and marine superintendent manager, or “shore captain,” for Consolidated Exporters in its later years: you could clear for any port in the world, but you didn’t actually have to go there.

Hudson told Ron Burton how it all worked in an interview. “So when we wanted to load, we went alongside [Ballantyne Pier] … and loaded quite openly. We had to put a big deposit down, I think it was twenty dollars a case. Say we cleared for La Libertad [Mexico] … We’d send our agent down there and he’d pay somebody off a few hundred bucks and he’d send back a release [the landing certificate] … and we presented this to customs … and all our money was returned!” Then it was only a matter of getting the clearance papers back out to the mother ships sitting out on Rum Row.

In February 1924, with liquor pouring across the line, Ottawa finally caved in to the constant pressure from Washington, DC, but only resolved the issue with a half-hearted measure. Now, it announced that it was no longer going to allow the smaller vessels in the rum fleet to clear for distant points such as Mexico or Central America, which the owners quite obviously never intended to reach. To get around this, liquor merchants and export companies changed their clearance papers for destinations along the BC coast.

In the end, these measures didn’t slow things down much at all. From then on, it was simply a matter of consigning several hundred cases of whisky to an up-coast port like Bella Coola or even Bowen Island, regardless of the fact that there was hardly anyone living out there to drink them. Meanwhile, boat and cargo steamed off in the opposite direction towards Puget Sound or farther down the American coast. “I’m sure that if the records for that period were examined, places like Bowen Island would show a per capita alcohol consumption that far exceeded human capability!” This according to Johnny Schnarr, one of the most successful West Coast rum runners, as told to his biographers, niece Marion Parker and Robert Tyrrell, in Rumrunner: The Life and Times of Johnny Schnarr.

A few months later, Washington, DC, itself made a move to curtail the ever-growing flood of liquor pouring into the country. They signed a revised liquor treaty with Great Britain which was proclaimed by President Calvin Coolidge on May 22, 1924. At that time, Great Britain still represented Canadian interests and maintained jurisdiction and control over Canada’s territorial waters.

The revised treaty extended the standard three-nautical-mile international territorial limit to twelve nautical miles or one hour’s sailing from the US coast. This was in order to make it harder for the smaller and less seaworthy craft to make the run from international waters to the beach. But most importantly, the treaty allowed for any ship sailing under the British flag and suspected of carrying liquor to be searched if it was within an hour’s steaming distance of the US coast. As it was, small, fast boats were easily outrunning Coast Guard ships to dock or land in small, out-of-the-way bays and coves or even run up a river along the California coastline where the cargo was landed and transferred to waiting automobiles or trucks.

Of course, federal officials in Washington, DC, continued to pressure their counterparts in Ottawa to restrict companies from loading liquor in Canadian ports, only to deliver it up to American vessels. Officials were well aware of the fact that they never did stop in at any Mexican, Central or South American port to unload as declared on their fake landing certificates. It wasn’t until 1930, however, that the Canadian government introduced a bill to amend the Canada Export Act requiring that all Canadian ships clearing for a foreign port loaded with liquor proceed to that port and actually discharge their cargo there. Although it was not officially passed until March of that year, rum running interests like Consolidated Exporters had already found a clever way to legally circumvent this requirement by actually delivering liquor to their stated destination. It was simply a matter of locating a friendly transshipment port with suitable warehouse facilities and, most of all, easygoing port authorities who weren’t really concerned about whether a particular cargo was actually unloaded in their port or not.

Tahiti became the destination of choice, and mother ships or their supply ships settled into a routine of sailing from Vancouver to the tropical customs-free port of Papeete, much to the delight of their crews, before crossing back over the Pacific to Mexico to continue on with their trade (in the latter years of Prohibition, Rum Row was finally situated just south of Ensenada, Mexico). The whole undertaking proved straightforward and easy to manage. Once the Canadian merchandise arrived in Tahiti, all it required was a little creative paperwork, and most likely paying off port and customs officials, and sailing back across the Pacific to Rum Row. Then once the mother ship was sitting out on Rum Row and its cargo had been delivered up, stocks were then replenished from Tahiti aboard sailing schooners ranging from the two-masted Aratapu (Peruvian) to the big three-masted Marechal Foch (Tahitian), as well as several others. The rum fleet was also kept well supplied from other customs-free ports besides Tahiti.

Regardless of Rum Row’s location or the logistics, the whole operation remained above-board, involving nothing criminal or untoward. As Hudson stressed in his interview, “We operated perfectly legally. We considered ourselves philanthropists! We supplied good liquor to poor thirsty Americans who were poisoning themselves with rotten moonshine … and brought prosperity back to the harbour of Vancouver … Many people thought of rum running as a piratical trade …” Instead, “it wasn’t anything dangerous. Simple, clean business operation from start to finish, no firing or hijacking, nobody lost or drowned or killed, good wages, paid well, a bonanza in Vancouver because Vancouver was in the dumps!” This proved especially true during the early years of Prohibition, when rum running remained mostly a trouble-free way to earn a fast dollar, especially for those who might own an old fishboat, packer or towboat with a reasonably sized hold, if not crewing aboard a mother ship. The only real threat was from hijacking. It was the Americans who took all the risk and who needed the fast hulls in order to outrun their own Coast Guard once back in US waters. Even so, the US Coast Guard was dreadfully lacking in patrol boats at the onset of Prohibition.

Still, there were also some major costs to bear that played out over the fourteen years that the Volstead Act remained in effect south of the line. Of course, throughout the United States there were particularly tragic consequences that arose from Prohibition. Right from the very start, bootlegging soon fell under the command and control of America’s very own sophisticated management entities, those of the criminal element. And as the 1920s progressed, the downside to all the high adventure and romance of running booze out of Canadian waters began to reveal itself. Even so, the tales of high adventure around local waters and down the American coast still resonate, especially following the publication of memoirs later in life by some of the characters that took advantage of Prohibition in order to earn a good dollar.