Chapter Two

Showdowns in the Strait

While rum running was generally a relatively harmless and violence-free undertaking along the West Coast, especially if carried out in Canadian waters where literally hundreds of transactions took place, there were some dramatic events involving hijacking that grabbed the headlines in the early years.

“Pirates Prey on Rum Runners” is the headline citizens of Victoria were shocked to read upon opening their Daily Times evening newspaper on January 16, 1922. It was a fascinating albeit short tale, highlighting the dangers, especially to small operators, of making surreptitious liquor smuggling runs across the border. Apparently, Charles Boyes had just returned to Vancouver minus his fast motorboat and cargo of whisky, as well as a substantial bankroll. He had been running comparatively small cargos into Puget Sound points and on this particular trip, was carrying fifty cases of liquor.

Boyes informed a reporter that he had been playing a “lone hand” but had decided the week before to take a partner and so invited “Omaha Whitey,” who was over in Victoria at the time, to join the enterprise. Upon his arrival in Vancouver, Whitey learned that Boyes was overdue from his trip. Then he received a wire from Bellingham asking him to forward funds as Boyes was in some sort of trouble and very eager to get back to Vancouver.

After he had crossed the line into Washington state waters and was cautiously looking for the agreed-upon landing place with his running lights doused, Boyes was overhauled by a larger and faster boat, also running with no lights. When the unidentified boat ran up beside him, three men jumped aboard with revolvers in hand, shouting, “You are under arrest. We are US federal officers.” They quickly set upon him to carry out a body search and relieved him of his $2,100 emergency fund, saying they were seizing the cash as evidence. (Since a 1922 US dollar would be worth close to $14.50 in 2017 dollars, Boyes was carrying around thirty grand in today’s money.) After leaving two men in charge of his boat, they forced Boyes aboard their craft and set a course for Bellingham.

Before they got there, however, they landed on a quiet beach where they shoved Boyes into an automobile. They informed him he was on his way to jail to await trial in Bellingham. But upon reaching the outskirts of the city, the car pulled over. Here the “officials” ordered Boyes out of the car and told him to beat it.

As he stood there and watched the car race away into the darkness, he quickly realized that he had been the victim of pirates. Not willing to admit he’d lost everything, Boyes made “careful inquiries” around Puget Sound to try and locate his missing boat, fully aware of the fact he couldn’t appeal for aid from American officials. Once he resigned himself to the fact that he was out of luck and had lost it all—the boat, his cargo of liquor and his bankroll—he wired for money and returned to Vancouver. Still, Boyes had got off lucky since hijacking, especially in American waters, only got more violent over the next few years as Prohibition set in. As it happened, the manufacture, distribution and imbibing of alcohol in the United States of America had been illegal almost two years to the day at the time of Boyes’s loss.

The most feared of the American hijackers were the Egger brothers, Theodore “Ted,” thirty-two years of age; twenty-nine-year-old Ariel “Happy”; and Milo “Mickey,” who was twenty-six; famous for their black-hulled speedster Alice, powered by a two-hundred-horsepower Van Blerck gasoline engine. But it wasn’t just their fast boat that made their reputation in the early 1920s. Rum runner Hugh “Red” Garling described them as the most unscrupulous, brutal, hardened criminals known throughout the Pacific Northwest during their brief career. He noted that for eighteen months between 1922 and 1924 the Egger boys brought to the Gulf Islands, San Juan Islands and Puget Sound waters “an interval of terror.” The returns for American rum runners were particularly rewarding since they were able to buy whisky from Canadian carriers for around $25 a case and then sell it in Seattle for up to $225 a case. But the Eggers decided this wasn’t quite good enough and turned to piracy in order to obtain it gratis.

One day while tied up at the float at Discovery Island, Johnny Schnarr, a Canadian who was earning a good living “jumping the line,” and his partner noticed a boat painted completely black pulling into the bay. He described the two men as rough-looking characters, both hawk-faced and raw-boned, and he didn’t like the looks of them at all. When they began asking all sorts of questions about the price of liquor but didn’t seem all that interested in buying any, Schnarr and his buddy got suspicious. Alice shadowed them for a while after Schnarr and his partner picked up their liquor and set off for Anacortes, but the evil-looking boat finally turned away and headed off in another direction looking for easier pickings. Schnarr figured his demonstration of skill shooting bottles out of the water with his Luger while waiting at the Discovery Island float probably discouraged the desperate-looking characters from bothering with them. It was only when they were back on Discovery Island a week later that they learned that they’d met up with a couple of the notorious Egger boys.

Hugh Garling claimed that the first victim of the Eggers’ cross-border piracy was Tom Avery of Vancouver in his boat Pauline. The Eggers relieved him of the 128 cases valued at $5,376 he was hauling for Great Western Wine Company.

The boys’ next attempt at hijacking was the 73-foot fish packer Emma H, which they came across anchored in Smuggler’s Cove on the inside waters of the Discovery and Chatham Islands in May 1923. The Eggers rowed over in a dinghy with automatics drawn only to be met by Captain Emery and crew armed and ready for them. Somehow, after convincing Emery that their boat was too cold and damp, they managed to talk themselves into spending the night aboard Emma H. A wary Emery agreed but posted an armed guard to keep an eye on them throughout the night. Giving up on this particular knockoff, since the Eggers were probably reluctant to shoot it out, the trio returned to Alice and headed off for nearby D’Arcy Island. Here they found another fish packer being put to good use in the trade, the 31-foot Erskine, whose cargo they were more successful in purloining at gunpoint. They ordered its captain, a fellow named Steele, to proceed at full speed across into Washington state waters to Dungeness Head, just east of Port Angeles on the Olympic Peninsula, where they beached Erskine, disabled her engine, cached half her cargo of liquor, transferred the other half to Alice and took off. Unfortunately for the Eggers, they’d chosen the wrong boat to hijack since it was running liquor for Roy Olmstead.

Emma H, a two-masted halibut schooner 73 feet in length, was soon to be recognized as “the Hulk” and put to use in a more lucrative trade—transferring liquor orders to Yankee boats out in Haro Strait. From the collection of Canadian Fishing Company.

Olmstead was a former Seattle police officer who displayed a natural talent for organization and administration when he put together a sophisticated wholesale rum running operation in Washington state. After many Seattle residents became tired of the vicious competition and chaos in the illegal liquor market in the early years of Prohibition, Olmstead encouraged some prominent local citizens to invest in an international company to operate and control a wholesale liquor enterprise, thereby bringing some sanity to the risky and illegal business. Olmstead got off to a good start by first bribing both American and Canadian customs officials so he could lay out a safe rum running route between the two countries. The first exchange point he established was D’Arcy Island just outside of Victoria, where the Eggers chose to hijack Erskine and make off with its shipment. This infuriated Olmstead. The Eggers messing with the wrong guy, one who had all the right connections, was probably a big factor that led to the American authorities finally catching up with them a year later. But, for whatever reason, the attempted holdup of Emma H and hijacking of Erskine just off the Victoria waterfront didn’t make the news in local BC papers. Perhaps the victims weren’t all that willing to share details of their unsavory operations with a reporter. (While both Johnny Schnarr and Hugh Garling gave very detailed accounts of some of the rather nasty incidents that went down in local waters years later, they always remained discreet and didn’t give away the names of their sources even though the incidents they recounted had occurred more than fifty years earlier.)

The next known at-sea stickup perpetrated by the Eggers was that of the Canadian-owned Lillums, near Hope Bay on North Pender Island in August 1923, when the Egger gang made off with sixty-three cases of liquor. Adolf Ongstad and Jack Webstad were operating the runner. Webstad had gone off to look for a guy named Thompson who they were to rendezvous with at Bedwell Harbour on South Pender Island, leaving Ongstad to stay with the boat. Sometime later, while dozing in his bunk, Ongstad was disturbed by the sound of a powerful engine close by, and when he peered through the porthole, saw Alice coming alongside. Then the cabin door was pushed open and Ongstad found himself looking down the barrels of pistols in the hands of the Egger brothers and their accomplices, ex–prize fighter P. K. Kelley and two thugs named Pfleuger and “Tiny” Palmer. Once aboard, the lines to the dock were cut, Lillums was secured alongside Alice and they headed out into Navy Channel where the liquor cargo was transferred over and Alice raced off into American waters.

It wasn’t until March 1924 that the gang was back in the Gulf Islands again. Kayak—manned by two Seattle runners, “Feathers” Martin and engineer Joe Edwards—was patiently waiting to rendezvous with the Canadian boat Hadsel, operated by Fred Davidson and his engineer, Adolf Ongstad, at Peter Cove at the south end of North Pender Island. Kayak was to take on an order of 293 cases of Scotch, which Hadsel had loaded in Vancouver and which had already been paid for. That night, while Kayak sat moored awaiting the arrival of the BC rum runners, four masked and armed men in a dinghy snuck aboard the boat and caught the two Seattle men by surprise. After Martin and Edwards were tied up, the visitors settled in for the night frying bacon and eggs, brewing coffee and generally making themselves comfortable. When Hadsel arrived just after daybreak the next morning, Mickey Egger rammed a .45 automatic in Martin’s back and told him to stick his head out of the hatchway and signal across that everything was all right and to come alongside. Once Hadsel was within hailing distance, they jumped up shouting, “Stick ’em up!” and started shooting, riddling the wheelhouse with seventeen shots. Davidson automatically reached for his Winchester but after taking a couple of shots in the shoulder and ankle, quickly surrendered and the Egger gang jumped aboard. The four desperados unceremoniously dumped the two Canadians onto Kayak and took off in Hadsel. The Eggers then ran her into a nearby bay where they transferred the liquor cargo over to their boat, Alice. Once loaded, they opened up the throttle to roar back into American waters.

San Francisco police finally arrested both Happy and Mickey on a charge of highway robbery in November 1924, while Ted was picked up sometime later in 1925 in Tacoma, and the Eggers’ reign of terror, both in Puget Sound and Canadian waters, came to an end.

But, as Johnny Schnarr pointed out, by that time the threat of violence had one side effect: all those involved in the business started packing firearms, while some were scared off completely. He said that it was getting to the point where there were just too many trying to make a fast buck running liquor in local waters and the resulting competition was bound to drive down the delivery price. Regardless of the danger posed by the likes of the Egger boys, Canadians involved in the liquor trade still remembered the early years of US Prohibition as golden ones.

Around the same time that the notorious Eggers were being hunted down in the States, two Canadians, William J. Gillis and his seventeen-year-old son, fell victim to the brutal hijacking of their 53-foot wood packer Beryl G off Sidney Island by two hard-bitten thugs. This time the rum runners not only lost all their liquor but their lives as well. Don Munday, who wrote up the tragic tale in the BC Provincial Police magazine, The Shoulder Strap, in 1940, called it “the most ghastly episode of lawlessness in British Columbia waters during the rum-running years.” He also noted that it resulted in a “relentless police effort to solve a cold-blooded killing carried out with diabolic cunning.”

Once word was out around local waters about the brutal hijacking of the Beryl G, the local rum running fraternity vowed to hunt down those responsible for the murder of Captain Gillis and his son and shoot them on sight. Leonard McCann Archives, LM2018.999.032, Vancouver Maritime Museum.

On September 17, 1924, Chris C. Waters, light keeper at Turn Point, Stuart Island, on the US side of Haro Strait, noticed a boat drifting northward past the lighthouse and figured it must have had engine troubles and broken down. Waters crossed the island to ask the husband of the postmistress to bring his gas boat around, and the two went out to see what the problem was. As they pulled alongside the drifting craft, which they now identified as Beryl G, they banged on her hull. But there was no response. Thinking they were dealing with an abandoned boat, they decided to put a line on and tow her into Stuart Island but when they came alongside they noticed bullet holes in the fo’c’sle door. Once aboard, they were shocked to discover bloodstains all over the hatch covers and along the deck, as though something heavy had been dragged over them. Up on the bow they came upon a pile of blood-soaked clothing, and inside there was even more blood all through the companionway and spread over the stove and the settee. Now fully aware that something terrible had gone down, they contacted the US Coast Guard, who quickly notified the British Columbia Provincial Police, as Beryl G was registered in Vancouver.

In a story on the incident in the October 1989 issue of Harbour & Shipping, Hugh Garling said that Beryl G, which was named after Captain Gillis’s daughter, had been used for freighting supplies to logging and mining camps up the British Columbia coast prior to becoming a packer. Don Munday, still a well-known BC mountaineer and naturalist, worked up a story on the most violent hijacking of a vessel in BC waters, which appeared in the winter 1940 edition of The Shoulder Strap. Munday wrote that besides operating her as a freight boat, Gillis was also trying to make a go of it with a small oyster cannery, but a poor season had set him back. The subsequent investigation revealed that Gillis had been approached by an agent for well-known Seattle rum runner Pete Marinoff, who was looking for a Canadian to freight liquor for him.

Gillis accepted the offer to make a fast buck and was sitting on the anchor around midnight on the east side of Sidney Island after making his fourth transfer of 110 cases from Beryl G’s cargo of 350 cases across to Pete Marinoff’s boat, M-453. (Marinoff had paid twenty-eight dollars a case.) M-453 was an ideal rum runner, a twin-screw “fast launch,” 56 feet long, powered by twin three-hundred-horsepower Sterling engines and capable of thirty knots. Conflicting reports say that Beryl G was carrying anywhere from 350 to 600 cases of liquor at the time, all loaded from “the rusty old British freighter Comet” that was sitting outside both American and Canadian territorial waters off Vancouver Island’s west coast. Marinoff sent the money out for his order of 110 cases but no money was found aboard the abandoned vessel when provincial police examined the ill-fated craft.

But all they came across were the bloodstains and bullet holes in the woodwork, along with what appeared to be signs of a struggle: all evidence suggesting that murder had been committed in the midst of a hijacking. While police authorities on both sides of the border set out to locate and capture those responsible, the local rum running fraternity also became involved. They were outraged that their lucrative trade, which was sustaining so many mariners on both sides of the border, was now being threatened by the criminal element. Victoria’s Daily Colonist reported on October 10, 1924, that in Vancouver, leading rum runners had banded together to run down the murderers of Captain Gillis and his son and vowed to shoot them on sight. Still, it was British Columbia’s very own Provincial Police force that would track down the culprits.

Vancouver Island fisherman Paul Strompkins (“a big, fat-faced Pole, a former Manitoba farmer turned fisherman,” as Don Munday described him) was caught and arrested on Vancouver Island. He’d been picked up because of his past record and Canadian customs officers confirmed that he had been smuggling beer. Also, he happened to have introduced a customs officer in Beacon Hill Park to several Americans, one being an individual named Owen Baker. After a few other clues emerged that put him under suspicion, Strompkins broke under constant grilling and promised to come clean. After careful inquiries down along the Seattle waterfront, Inspector Forbes Cruickshank, in charge of the Criminal Investigation Branch and recently assistant commissioner of the BC Police, went with two King County detectives and arrested Charley Morris. Then, after a reward of two thousand dollars was offered for each man, Owen Baker was picked up in New York, where he was working on a barge under the alias of George Nolan, while Harry Sowash was picked up in New Orleans by local detectives who recognized his photo in a magazine circulated among US police forces. All three were then extradited to British Columbia to stand trial.

At the trial, it was revealed that Strompkins had embarked the three American desperados in Cadboro Bay close to the Royal Victoria Yacht Club in his “beer boat,” Denman No. 2, to take them out to Sidney Island. (The trio probably avoided using Dolphin, the boat they’d chartered from Albert Clausen, who ran an auto repair shop in Seattle, since she was too easily recognizable as a fast hull probably used for running liquor.)

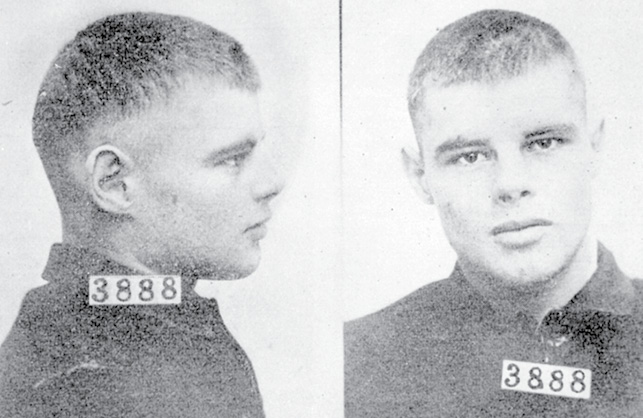

Cecil “Nobby” Clark, who served for thirty-five years in the BC Provincial Police and became the service’s unofficial historian, writing numerous articles for local papers along with a series of books on BC crime, described the three ruthless characters in one of his stories, “Hijack Route to the Hangman”: “Owen W. Baker was tall and gangly, with an Adam’s apple that moved convulsively in his scrawny throat. A lock of hair falling over his forehead gave him a folksy look that belied the savagery he later revealed. Harry “Si” Sowash was somewhat younger, and with his crewcut, broad shoulders and rugged build, he could have been taken for a university football player. In keeping with this academic impression, he read a lot and knew his way around in Greek and Roman history.” The two met in McNeil Island penitentiary down in Puget Sound. Owen “Cannonball” Baker was doing a five-year stretch for white slavery while Sowash was serving two for selling stolen airplane parts. They were both released during the heyday of rum running and were soon taking advantage of the opportunities it presented.

In early September 1924, Baker, Sowash and their new accomplice, Charley Morris, had been cruising off the west coast of Vancouver Island in Dolphin for a number of days, searching for liquor caches, when they happened to notice the Beryl G off Sooke Harbour, headed for Victoria waters. The trio soon determined that the boat was shuttling booze to the east side of Sidney Island, where her cargo was delivered up to American boats. Once Strompkins turned king’s evidence, it didn’t take long into the trial to learn the gruesome details of the murders. After dispatching father and son, the three American thugs handcuffed the two bodies together, stripped them of most of their clothes and then ripped the bodies open with a butcher’s knife so they wouldn’t float once heaved overboard. Found guilty of murder, Baker and Sowash were sentenced to hang on September 4, 1925, while Morris received a life sentence. Strompkins was also charged with murder, but since the Crown was unable to find any evidence directly linking him to the murders, he was discharged. The date of execution for Sowash and Baker was advanced and on January 14, 1926, they were both hanged in BC’s Oakalla prison.

Owen “Cannonball” Baker was described by Don Munday, who worked up a detailed story on the hijacking of the Beryl G in 1940, as “tall, dark, glib-tongued with a pasty complexion.” He said Baker also had a wife and child, whom he apparently wasn’t supporting all that well. Royal BC Museum and Archives, Image B-05758.

One wonders if perhaps it might have been Cannonball Baker who hijacked Charles Boyes back in January 1922 and made off with his boat, liquor and bankroll. (Harry Sowash wasn’t let out of prison until just a little before the Beryl G incident.) The modus operandi appears strikingly similar. According to Cecil Clark, Baker typically outfitted himself with a yachtsman’s peaked cap, a blue blazer with double rows of brass buttons, flashlight and a phony police badge. Out patrolling local Puget Sound beaches in the dead of night, he and his cohorts would sneak up and surprise the “rummies” unloading their boats by jumping up shouting, “United States customs! Stay where you are!” After the surprised rum runners took off for their vehicles, Baker “confiscated” their booze.

In the day before his execution on January 14, 1926, at Oakalla prison, Harry Sowash wrote in a letter: “A raging fire of regret, of remorse, a feeling of unfitness, a sense that I have cheated myself, torments me ... A short season of moral laxity is but the beginning of a swift, dizzy ride ... with a weary, stone path back.” Royal BC Museum and Archives, Image B-05759.

The Beryl G murders put the whole rum running trade on edge. As a consequence, the generally peaceful enterprise started to take a nasty turn for the worse. All those involved, whether directly taking part or trying to put a stop to it, started keeping a rifle or pistol well within easy reach. Now, shootouts and gunplay started becoming commonplace in southern British Columbia waters and even off the beaches inside the “Tweed Curtain” of Victoria’s plummy Oak Bay neighbourhood.

While accounts of violent encounters and hijackings by the criminal element out among the rum running fleet were grabbing headlines, US enforcement agencies weren’t shy about resorting to gunplay in order to try and put a halt to the trade in Washington state waters. Meanwhile, their counterparts in BC were also known to reach for their firearms in order to keep up the appearance that the liquor trade was all legal and above-board on their side of the line.