Chapter Three

US Coast Guard Gets Tough

On July 1, 1924, Victoria’s Daily Colonist ran a story under the sensational headline, “Big Whiskey Cargo Seized by Police,” which provided insight into how Canadians were interacting with their American brethren in local waters. “When the police launch Dorothy, a 32-foot yacht hired by the local police for use as a patrol vessel, arrived at the entrance to ‘Smuggler’s Cove,’ Chatham Island, on Thursday afternoon, its occupants were treated to a fast display of scattering.” The police launch came upon a dozen boats in the immediate vicinity and all but two turned about and made off when the launch drew near. When Dorothy entered the cove, she discovered three launches moored to the wharf. Seeing that one craft, identified as M-332, which indicated American registry, sat low in the water, the police boarded the vessel and a cargo of sixty cases of whisky, valued at $3,500, was found in her hold while the crew was nowhere in sight. A smaller craft, a Canadian boat, was found to contain a full cargo of cased beer, but as her owners had possession of all the necessary papers properly drawn, she was not molested. However, M-322 was taken into Cadboro Bay and handed over to customs officers.

The article continued that on returning to the Chatham Islands later that day, Dorothy was headed for the third vessel, a rakish-appearing craft which, from her depth in the water, probably carried a good load. “When the police boat was some distance away, one of the members of the moored boat’s crew cut the mooring rope, and despite threats to shoot from one of the officers on the Dorothy, the craft swung out to sea and in a remarkably short space of time had reached the horizon.”

Discovery and the Chatham Islands, with their quiet coves, narrow channels and close proximity to the US-Canada boundary, were an ideal rendezvous point for rum runners. Here a fellow and his wife even anchored their boat out behind Discovery Island at what became known as that island’s Smuggler’s Cove during the Prohibition years and sold beer to the Americans running across the line. Once sales began to pick up, they realized there was even better money to be made selling hard liquor. The couple then built a small lodge on one of the islands, where they offered good home-cooked meals to all those who were there waiting to pick up or deliver a load. They also built floats out into deep water so there was room to tie up right in front of the lodge.

With the rewards being so high, Canadian operators soon learned that they still had to be prepared to defend themselves since they were sitting ducks to the hardened American criminal element that wasn’t going to let any border get in their way. Those involved in trying to put a stop to the rum running weren’t prepared to admit its benefits. Only the year before, June 3, 1923, The Daily Colonist ran a front-page story under the headline, “Rum Runners Hard Pressed: Are Making Last Stand on the British Columbia–Washington Border.” In an interview in Spokane, Roy C. Lyle, Washington state federal Prohibition director, declared that a “tremendous flood” of spurious liquor (probably American moonshine) was now being offered in Seattle because rum runners were finding it more difficult to bring in liquor from Canada and that bootleggers and rum runners were making their last stand on the British Columbia–Washington border as a result of other provinces having been driven out the liquor export business. Nonetheless, whether his office was showing results or not, he hoped that laws would be amended to permit Prohibition officers to use confiscated automobiles, boats and airplanes in enforcement since, he lamented, his men were hampered by lack of equipment. But American law enforcement did eventually come into their own and could lay claim to some dramatic seizures and arrests by late 1924. And these involved vessels in the supposedly legitimate shipping and export trade operating out in international waters. As it happened, Canadian authorities were also making the odd seizure themselves.

Right beside the story on how rum runners in American waters were now “hard pressed,” the Colonist reported that, on this side of the line, law enforcement was also having some newsworthy successes. Following their efforts to break up an (unnamed) “rum-running gang which has been operating for months past with ‘brazen effrontery’ between Canadian and United States points in the Gulf, Provincial Police officers and customs authorities yesterday [Monday, June 4] made sensational seizures in the vicinity of Discovery Island near the spot where, on Saturday, they captured two Canadian launches, alleged rum runners, and two American craft.” The paper stated that great credit was given to the efforts of Provincial Constable Wilkie, Customs Officers Bittancourt and Norris, and Dominion Constable Harvey, for breaking up the ring. On Monday morning the four enforcement agents headed out in their launch, Ark, to look over the fish packer Emma H (or The Hulk, as she was better known around local waters. This was the vessel that the Eggers had unsuccessfully tried to hijack). The Emma H had apparently transferred her cargo over to Cleegone, a Canadian launch, the previous Saturday. It was seized and brought into Victoria the next day, Sunday. Once the inspection of Emma H was finished, she was left out on the spot and Constable Wilkie and the other officers continued with their investigation of neighbouring waters throughout the Chatham Islands. In a sheltered bay on Discovery Island, they came upon two power boats, one the Standard from Anacortes, the other unnamed. Two men found asleep on the Standard and one on the other vessel were caught by surprise and the crewmen were detained and brought into Victoria. And it wasn’t over yet.

The same four enforcement officers returned to Discovery Island in Ark later Monday afternoon. This time they came upon a vessel, Syren, passing booze over to two Yankee boats who, when they saw the Canadian authorities bearing down on them, made off towards the American side. And despite every effort to overhaul them, they made good their escape, with Ark having to call off the chase at the Canada-US boundary line. Syren also attempted to make a fast exit, but was overhauled and one American, a gentleman named Kerr, was arrested. Both Standard and the unnamed vessel from the morning capture were detained and brought into Victoria. Syren was brought into Victoria later that evening and tied up at the Causeway. While no liquor was found aboard Standard, she was seized, since she broken Canadian law by entering the country at a place other than a regular port of entry without the excuse of emergency to justify her action.

By late 1924 American enforcement had also achieved some successful seizures and arrests, although they were dreadfully lacking in vessels and manpower. In a Seattle news release in June 1924 it was reported that four men were seriously burned and three wounded by bullets when the coast guard cutter Arcata, out for rum smugglers, pierced the gasoline tank of their boat lying in Mutiny Bay, eighteen miles north of the city. Ignoring the fact that a quantity of Canadian liquor was found on the vessel and it was running without lights, one of the wounded protested that they were all just out on a hunting trip. He claimed that Arcata opened fire with her one-pound gun without warning and fired four or five shells, and that he was hit while standing at the wheel. This capture was quite a praiseworthy feat for the Arcata since she left much to be desired in her role. She was only 85 feet long, top heavy and unfit for the open ocean, and had a top speed of only twelve knots.

On Saturday afternoon of September 27, 1924, the crew of the 50-foot tug-turned—rum runner Ironbark were fired upon by Victoria-based customs officials as they attempted to board the vessel in Cadboro Bay to check her clearance papers. Victoria residents were astonished to read in their Monday Victoria Daily Times the sensational headline, “Escapes hail of bullets from customs men’s guns.” Apparently, the crew of the 57-foot tug Superior were working on a log boom in Cadboro Bay when they were startled by the sound of gunfire and bullets humming over their heads and promptly sought cover. Slipping and sliding over the logs of the boom, they headed as far as they could from the paths of the flying lead. As for Ironbark, she was registered to Coal Harbour Wharf and Trading Company of Vancouver and owned by Archibald “Archie” MacGillis, who had already established himself as a major player in West Coast rum running by that time.

R. Harrap, the steward at the Royal Victoria Yacht Club, was interviewed by the Times reporter about the attempted boarding. Harrap stated that about noon that Saturday, a party of men (who turned out to be customs officers) came down through the grounds of the club and quickly made their way onto the float. Assuming them to be visitors from another yacht club, he didn’t bother asking any questions. But when the strangers shoved two boats into the water, he ran down in an attempt to stop them. “Those aboard the Ironbark supposed the strangers were hijackers,” said Harrap. “The customs men, whom I did not recognize as such at the time, were armed and none of them were dressed in uniform. The Ironbark had legitimate clearance I believe … The Ironbark slipped her moorings eventually, and as the customs men got to within twenty feet of her, suddenly shot forward and twisted out into the bay, running clear of the shots of the officials,” Harrap added. In an attempt to explain their drastic actions, customs officials told the Times reporter that they did the best with the equipment they had, and they only intended to look over the launch’s clearance papers. And when she did not stop on their warnings, they opened up on her.

Ironbark was registered to Coal Harbour Wharf and Trading Company, which was owned by Archie MacGillis. He was considered one of the founding fathers of rum running working out of British Columbia waters. Leonard McCann Archives, LM2018.999.033, Vancouver Maritime Museum.

The shootout in Cadboro Bay was followed a week later by another Wild West encounter, this time with Eva B, which was disguised as a fishboat. It was owned by Seattle police officer turned rum running magnate Roy Olmstead. The capture of Eva B and its seven hundred cases of liquor by the Winamac, “a sturdy little craft, well suited for the work she was engaged,” took place at Portland Island off Sidney on October 5, 1924. As it happened, Captain Abraham Reid Bittancourt (who was from a pioneering Salt Spring Island family), was chartering the 47-foot wood launch to the customs service as a patrol boat and operating out of Ganges Harbour on Salt Spring Island when he received word from fishermen of suspicious activity out at Portland Island. Following up on the tip, Captain Bittancourt and his son Lyndell (“Len”), Winamac’s engineer, donned their customs officer uniforms, grabbed their rifles and called out to local police constable J. N. Rogers and forestry officer A. Warburton to ask if they’d care to come along for a little excitement. They did.

After making the hour-long run over to Portland Island early Sunday morning, Winamac made a point to pass well abeam of the north side of the island, so as not to raise suspicion while still allowing the captain and crew to be able to look back and spot the three vessels anchored in a bay. Once around a headland and out of sight, Captain Bittancourt turned close in towards shore and cruised back into the bay before the boats’ crews were even aware of their presence. One was a speedboat that was able to escape at some twenty-five to thirty miles an hour and get away to safety (Winamac, driven by a three-cylinder Corliss gas engine, was only good for nine knots at most), while “under a heavy fusillade of lead from the customs boat,” the two other vessels, an “innocent looking” fishboat and Eva B, made no attempt to run and their capture was inevitable.”

Originally built as a US Revenue cutter in Marine City, Michigan in 1892, the 47-foot wood vessel Winamac went on the Canadian registry in 1909. Here, a man who is probably Captain Bittancourt is leaning out the wheelhouse window as the workboat steams out of Victoria’s Inner Harbour. Drell and Morris Photographers, Ted Aussem collection.

Captain A. R. Bittancourt, pictured here with his wife and two sons, was from a pioneering Portuguese family that settled Salt Spring Island. He was freighting among the Gulf Islands with his motor launch Winamac when the boat and crew were hired by the Canadian Customs and Excise Department. The “sturdy craft” was also under orders to the fisheries and immigration departments. Salt Spring Island Archives, no. 992101004.

The Daily Times pointed out that “other customs officials state that it was one of the most adroitly made seizures ever made by local men, and all those accompanying him [Captain Bittancourt] are deserving of high praise.” Especially since “the Eva B is one of the many high-powered launches operating in the waters of the Gulf of Georgia, running liquor from the Canadian to the American side, and as the territory is wide in which these boats are known to be present, and there being thousands of hidden little nooks where they might well avoid the eyes of a half hundred Government boats, it is a feather in the caps of the men who took her.” (The “innocent looking” fishboat, which was having engine troubles, was set free since no liquor was found aboard.)

Later that day, Winamac returned to home base, Ganges Harbour, with her prize. There Winamac and the Eva B remained moored for the night with crew members retiring around midnight, leaving Constable Rogers to stand watch. The three American rum runners—Eva B’s master, Jack Rhodes; engineer Erickson; and “guest” Mr. Green (an ex-army officer who was actually the owner of the gas boat)—were taken up to the Ganges Harbour House for the night, where they were placed under guard. Around midnight, Constable Rogers noticed a strange launch slowly idling into the harbour, headed towards Winamac, apparently intent on coming alongside. He soon recognized it as the speedboat they’d surprised at Portland Island returning in an attempt to recover Eva B’s valuable cargo. Captain Bittancourt hailed the boat, giving it a warning, but still played it safe and kept his gun at the ready. But the occupants of the speedboat were just as quick to go for theirs and an exchange of bullets quickly broke out.

As Len Bittancourt recalled in 1965 to Imbert Orchard in a taped CBC Radio interview, “I thought I would get lots of sleep but then about midnight all the shooting that went on down here … I don’t know if they saw us but there was another vessel, the Three Deuces … a high powered launch and come there to hijack her [unbeknownst to them Eva B’s cargo had been transferred to the hold of Winamac] … but nobody got hit anyway. It was a little exciting here for a while; especially when you just nicely got into bed …” Encountering a stiff defence, the interloper retreated from range to open up her engine and race off down the strait.

The Three Deuces, which had reportedly broken the Lake Washington speed record at one time, was operated by Prosper Graignic, one of Roy Olmstead’s skippers, and propelled by a Liberty L-12 marine conversion—a four-hundred-horsepower V12 engine developed for the armada of fighters, bombers and observation planes built in the US during World War I. Graignic, who was described by Olmstead biographer Philip Metcalfe as “short and quiet,” was rumoured to have made almost four hundred trips for Olmstead by the spring of 1924.

Len Bittancourt explained in his interview how rum running was supposed to work—that is, if one was a Canadian citizen. Canadian boats were allowed to load a cargo and clear for a given point. “They’re not breaking the law … but [they did] break the law … when transferring it to an American vessel without supervision of a customs officer … As far as we were concerned they weren’t renegades and another thing, there was so many of them you couldn’t keep up to them! … But we did get the odd American.”

The Daily Times of October 7 reported that the morning after the Sunday night shootout in Ganges Harbour, Winamac brought the Eva B—“a fine, seaworthy craft, with a good cargo capacity”—into Victoria’s Inner Harbour. Rhodes, Erickson and Green were promptly brought up before a customs department board of inquiry and let out the following day on a $250 cash bond. Since they were unable to explain satisfactorily why they were in Canadian waters, they were turned over to the immigration department for deportation. But then there was the question of the mixed cargo of some seven hundred cases worth about four thousand dollars. (Around fifty-six thousand dollars in today’s money.)

There was some discussion following the seizure as to what was to be done with the captured alcohol. It was suggested that in the future when Provincial Police assist, all liquor be promptly destroyed on the spot, thus eliminating any fear of future attacks from hijackers. But in this case, which resulted in considerable financial benefit to the local customs department, the Provincial Police were rather annoyed since they didn’t see any of it, even though they took part and would have been willing to pay the regular customs duties.

Still, while it was the shenanigans occurring throughout the province’s southern waters just outside the large urban centres of Vancouver and Victoria that were grabbing the population’s attention, the waters off the west coast of Vancouver Island and along the entire BC coast right up to Alaska were to serve as major liquor entrepôts right up until Prohibition was brought to an end in 1933.

On October 22, 1924, a story titled “Seizure is a Mystery” in the Vancouver Sun noted that the position of the “liquor carrying boat Impala” upon her capture was somewhat baffling. (The Impala was a 47-foot, 8-inch wooden boat built in Vancouver in 1912.) It appears that Provincial Police were at a loss to understand what a liquor runner was doing out in Juan de Fuca Strait as far north as Bamfield since “the fleet has centred its operations in the Gulf of Georgia with bases on the numerous lonely islands off Victoria.” The discovery of a liquor boat off the west coast had them completely puzzled, and in particular, “where the Impala got her 483 cases of liquor and where she intended to take it are both questions which the police have been unable to answer so far.” The reporter went on to note that “the case, however, is being investigated carefully in an effort to uncover what is thought to be some new plan to outwit the Canadian Customs and the US Prohibition law. It was thought that perhaps the liquor smuggling fleet alarmed at the sudden new effort of the Canadian authorities to curb their operations may have decided to shift its base to a point far removed as practicable from the usual liquor running waters … the fact that the Fisheries Patrol Boat Givenchy was used to seize the Impala shows that all branches of the Federal Government service are cooperating in the attempt to curb the liquor fleet and its utter disregard for Canadian as well as American law.” It concluded with the note that while the Canadian authorities hadn’t decided as yet what was to be done with the Impala, “her captain and crew have told the Customs Authorities here that they are not guilty of violating any Canadian law.”

Still, it’s rather perplexing as to why Canadian customs was surprised by this development nearly four years into Prohibition, since there was already a flourishing liquor trade going on off the west coast of Vancouver Island. BC resident Richard Thompson recalled that when he was growing up, his family always wondered how it was that their grandfather never seemed to have to work. They only began piecing together the story of how their grandfather was able to retire early in life when they realized that he’d run a store at Spring Cove near Ucluelet from 1912 up until 1924. It seems that old Grandad had done rather well serving the rum running fleet in the early 1920s. Apparently, many a time boats showed up at the store’s float in the middle of the night and cleaned out all its stock.

Some accounts also have it that the proprietor of the village of Clo-oose’s store, just down the coast from Spring Cove, also provided a friendly service to the rum running fleet from her “thieves’ market” and was so successful that she was able to retire to a Vancouver hotel by the late 1920s. These particular “thieves” would have been the smaller vessels that were making runs to the mother ships out in international waters in the open Pacific off Cape Beale and Cape Flattery. Since the mother ships were required to sit out on the spot for weeks at a time, they most likely had fish packers or towboats that were delivering or picking up liquor stop in at Spring Cove and Clo-oose to replenish grub, oil and supplies. The west coast of Vancouver Island and the open waters of Juan de Fuca Strait were to remain a popular location for passing over liquor to American vessels right up until the end of Prohibition in 1933. Still, as Johnny Schnarr noted, there was a downside. By the early 1930s, there were so many American boats running out Juan de Fuca Strait to load, it drove the price down to five dollars a case. Up until that time, the Canadian boats had been getting eleven dollars a case.

Following the seizure of Impala, Victoria’s Daily Times reported on October 21, 1924, about “captured boats increasing in harbour waters”; the fleet of seized ships included Impala, Eva B and M-322 (the original account of her capture in July erroneously identified her as M-332). After noting that the Impala’s cargo was principally whisky and gin, those who inspected the freight she carried still had to decide whether she was guilty or not. Since Prohibition came to an end in British Columbia in 1920, the movement of liquor within Canadian waters was entirely legal. That is, as long as customs regulations were followed and, if the liquor was to be exported, the Canadian federal government paid its due. Otherwise Canadian officials tended to become somewhat irritated.

The customs department continued to maintain a watchful eye on rum running marine traffic. On October 14, 1925, they seized the packer Kiltuish as she arrived at the William Head quarantine station just outside Esquimalt harbour, apparently after having unloaded her liquor cargo at sea. The 87-foot, 7-inch fish packer was registered to Arctic Fur Traders Exchange Limited of Vancouver, and owned by Archie MacGillis and Frederick Rae Anderson, barrister. When customs officers inspected the vessel, they were rather annoyed to discover she had sailed for a foreign port with only coastwise clearance papers. As The Daily Colonist pointed out, regardless of the fact that steamers that were plying between Victoria or Vancouver and California were generally spoken of as being in the coastwise service, this didn’t mean that vessels could clear for California ports with coastwise papers. According to customs regulations, any port outside of Canada, whether it was down along the American west coast or in another country, was considered foreign.

After paying a four-hundred-dollar fine for the infraction, Kiltuish was released to continue on its way to Vancouver, and in 1927 joined the fleet of Consolidated Exporters, the big-time liquor export consortium working out of downtown Vancouver.

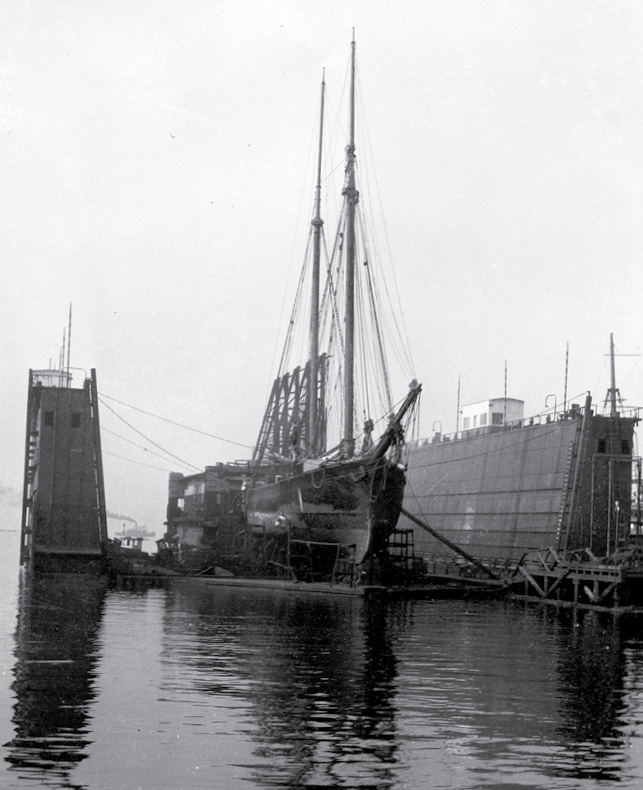

The Kiltuish was just one in the fleet of small boats and operators willing to reap handsome rewards through rum running in southern BC waters during the US Prohibition years. On January 24, 1925, it was reported on The Daily Colonist’s Marine and Transportation page that the two-masted auxiliary schooner Lira de Agua was in berth at the Ogden Point docks, loading a large consignment of liquor bound for Corinto, Nicaragua. Shortly after returning from her voyage to southern waters, the vessel was seized off the west coast of Vancouver Island by Canadian customs officers. She was alleged to have transferred one thousand cases of liquor to the Ououkinish, another two-masted auxiliary schooner, while still in Canadian waters. Because the transfer was made in Canadian waters, following her alleged delivery to a foreign country, it seemed likely that she didn’t have the required coastwise clearance paperwork aboard for doing so.

In October, later that year, the Victoria daily reported that Lira de Agua was to be confiscated by the Government and eventually sold, provided that the case was not appealed by the owners. Lira de Agua—which at one time had been used in the making of Hollywood films—was originally purchased in 1922 by R. M. Morgan and Company of Vancouver, to all intents and purposes for “coast freighting” as Mr. Morgan informed a Vancouver Sun reporter at the time. He also pointed out that he had no intention of changing her Nicaraguan registry since she was to ply up and down the coast between Vancouver and Fasceta Bay, Nicaragua. Shortly thereafter Morgan sold the schooner to Northern Freighters, which was owned by the well-known local brewery and distillery interests, the Reifel family. As for the 56-foot, 4-inch Ououkinish, a former halibut schooner, she was registered to the Atlantic & Pacific Navigation Company, another shipping subsidiary owned by the Reifel interests. The Colonist noted that the vessel was seized over on the mainland for her role in the transgression.

Also, that fall of 1925, the two-masted auxiliary schooner Chakawana, with a crew of five aboard, was seized off the west coast of Vancouver Island, this time by customs officers aboard the Royal Canadian Navy training ship and occasional fishery patrol vessel, HMCS Armentieres. The 62-foot Chakawana, which was owned by Archie MacGillis’s Coal Harbour Wharf and Trading Company, was brought in for having liquor on board that had not been loaded under customs jurisdiction, but was released on security. The cargo consisted of nine hundred cases of various liqueurs and whisky.

In April 1923, the Vancouver Sun reported that R. M. Morgan was to use Lira de Agua, a schooner that had been used in the making of Hollywood films, for coast freighting. Leonard McCann Archives, LM2018.999.034, Vancouver Maritime Museum.

In his book Slow Boat on Rum Row, Fraser Miles tells of his first voyage aboard the fish-packer-cum-rum-runner the 61-foot, 7-inch Ruth B in December 1931. They made transfers at contact points off Cape Beale but he noted that they ventured as far north as the Queen Charlotte Islands (today’s Haida Gwaii) to sit out off Alaska waters. Here they would wait for a radio call from Vancouver ordering them to release cargo to American boats. While nowhere on the scale of the smuggling that was being carried out down south, there was quite a flourishing trade working out of Prince Rupert and nearby waters. Olier Besner, one of Prince Rupert’s most colourful characters, jumped right in when the Volstead Act was enacted and set up a “fox farm” out on the Kinahan Islands just outside the entrance to Prince Rupert. For all intents and purposes, the “farm” served as a depot for exporting liquor into Alaska. In his biography, Charlie’s Tugboat Tales (written by Prince Rupert resident Bruce Wishart), Captain Charlie Currie, who was working on a pile driver nearby at the time, described how Besner ran his export terminal: “Well, they had a place you could back right in there in the dock, and a little winch and a derrick … It was quite often one of those big American seiners would come in there, back in and just load up right full of booze. It was never in boxes, all of it in sacks that would sink if they thought they were gonna get pinched … they had signs around the beach at Kinahan: Fox Farm. That was just a blind you see …” Unfortunately, Besner was being hijacked regularly and even tried sinking sacks in the ocean to evade the hijackers, but still, they posed enough of a problem that he decided to quit the business. In the end though, it seemed he came out of it all right financially. In 1928, Besner built a beautiful building on Prince Rupert’s main street in the Spanish Colonial Revival style, the Besner Block, which still stands to this day. He also owned the Besner Apartments and was a charter member of the city’s board of trade.

Overall, there were countless individuals in the rum running trade who became very adept at eluding both American and Canadian law enforcement agents, along with the criminal element, in order to earn a decent and often very lucrative living. As Hugh Garling said, “For every boat seized, the smugglers reaped $1,000 from successful sales, and for every man arrested hundreds more ignored the law.” While the local cross-border trade in illegal liquor was a dangerous business fraught with risk, there was also another method of freighting into the American market that was more benign, a daylight operation that was generally quite open and legal. Large mother ships loaded liquor from bonded warehouses and then made deep-water voyages to sit off the coast of California in international waters or in later years to anchor out just south of Ensenada, Mexico. Here, they supplied smaller freighters that delivered orders to buyers’ boats, which then assumed all the risk by having to transport the illegal cargo into out-of-the-way beaches along the American coast.