Family Dynamics:

Living in Two Worlds

“I have come to suspect that life itself may be a spiritual practice. The process of daily living seems able to refine the quality of our humanity over time. There are many people whose awakening to larger realities comes through the experiences of ordinary life, through parenting, through work, through friendship, through illness, or just in some elevator somewhere.”

—Rachael Naomi Remen

In a home where what is abnormal becomes the norm and what is normal can seem increasingly elusive, one learns not to be surprised by anything. The rules and routines in an alcoholic family are constantly in an unpredictable state of flux—that is, the same behavior that gets you applause one day gets you grounded the next. Identities, roles, and relationships can be unstable. They shift based on the moods and needs of the parent rather than the needs of the developing children or the family as a whole. CoAs live in two worlds, and the thinking, feeling, and behavior for each world can be radically different. For example, while Dad is on a binge, Mom and Lisa get so close. Mom leans on Lisa to help her with Danny, and Lisa and Mom become confidants and best buddies. Lisa shares Mom’s thoughts, worries, and interests. Lisa feels important and needed and elevated above kid status. Danny gets to run a little wild when Dad isn’t calling him on his behavior. Mom is “easier” and he gets away with more.

But when Dad sobers up, Mom and Dad get close again, and Lisa is now treated like a child. Suddenly Mom is telling her to do her homework and clean her room. And when Lisa asks Mom the same kinds of questions she asks when Dad’s drinking, Mom shuts the door and tells her to mind her own business. Danny comes to Lisa for company and she doesn’t even mind all that much; in fact, she comes to rely on his needing her—he helps to fill the now vacant space so she isn’t so lonely.

Another scenario is when Mom is drunk. She spends most of her time in her bedroom, so the kitchen—usually a part of her domain—feels suddenly empty. But available. Charlie and Betsey can do almost anything they want during the day when Dad’s at work. They have the run of the house; they pick up groceries “for Mom” and add cigarettes and beer whenever they feel like it. And they can smoke and drink in the basement because Mom never comes out of her room. And Dad spends more time at the office.

But when Mom gets sober for a week or two or three, suddenly the house feels completely different. No more beer or cigarettes, and credit card purchases are checked out.

Then there is the scenario of the functioning alcoholic, the one whose cocktail hour is sacrosanct, the one who has learned just how much drinking he or she can get away with during the week, on the weekends, and over family vacations. Or the pot smoker whose family feels like life doesn’t quite get started, or the cocaine user whose behavior is erratic and scary and changeable. Maybe Dad exercises just enough, eats just enough, and socializes just enough to ameliorate some of the negative effects of daily alcohol. He has the family well trained to not talk about how frustrated or worried they are, how Dad’s health issues are cropping up, or how his time with the family just feels sort of . . . affected. These more hidden forms of addiction can be very hard on family members. Their perception that something is off or missing is never validated, and they are left to doubt themselves, which leads to anxiety.

When a substance or compulsive behavior rules family dynamics, family gravity gets thrown off kilter: sometimes it pulls too hard and we can’t escape; sometimes it barely holds us in place. Kids learn to manoeuver in and out of their parents’ moods, which rule the atmosphere, so CoAs become parentified children—little caretakers who from a young age learn how to manage problem adults. Or they have to develop a premature “independence” before they are ready and they do not learn how to reach out and get help with their normal developmental problems. And they can feel helpless and despondent, unable to do anything that can really lead to their family getting better, happier, or safer. CoAs develop a sixth sense of when to hide, when to run, and when to hurl themselves straight into the breach and bring their parent—who is whirling out of control—back from wherever they have gone. They become little soldiers of fortune—determined, committed, and filled with zealous love—but their battleground is the home where they live, and the fortune they seek is a smile and warm touch from a depressed mother, the goodness and strength returning to their drunk father, or the magic of a quiet evening at home just being, hanging out, and doing lots of sweet, normal nothing.

CoAs who repeatedly find themselves “alone” to manage situations that they experience as difficult or confusing may learn some bad lessons, and miss learning some good ones. These lessons may include:

• Emotional hiding: They learn to hide what they are really feeling.

• Unconscious emotional defenses: They learn not to feel,

to numb out, or to split off/dissociate from pain.

• Semiconscious defenses: They learn to minimize, deny,

or intellectualize problems rather than deal with them openly and directly.

• Projection of feelings: They learn to make their pain about someone or something else, just as their parent does.

• Relational fear or mistrust: They learn that love, need,

and dependency can lead to pain.

The good lessons CoAs may not learn include:

• How to regulate their emotions by translating feelings into words and talking them out rather than acting them out.

• How to move away from feeling helpless, frightened, and overwhelmed and toward feeling re-empowered, centered, and balanced without self-medicating.

• How to work things out with another person in healthy ways so both people get to feel good again.

CoAs may also develop unusual strengths at an early age. The good lessons CoAs may learn include:

• How to manage frightening situations and keep their cool.

• How to have compassion for the suffering of others.

• How to tolerate pain and fear and continue to mush

on in spite of the pain and fear in their own lives.

• How to be self-reliant and take bold action on behalf

of themselves and others.

• How to come up with creative solutions to problems.

• How to trust their own “guts” and follow their own instincts.

• How to see the silver lining in a situation.

• How to reach out to others for help and support.

• That life can be challenging and disappointing but

still wonderful.

ACoAs can be remarkably creative and interesting people; managing unmanagability from such a young age helps them develop some serious competence at it. They know a lot about plowing through and doing what needs to be done and coming up with original and unusual strategies to get things accomplished, and they can have a pretty side-splitting sense of humor while doing it. Additionally, ACoAs who learn to forgive and trust again have a kind of acceptance about life that is inspiring and motivating. One that can lead to deep happiness and vitality.

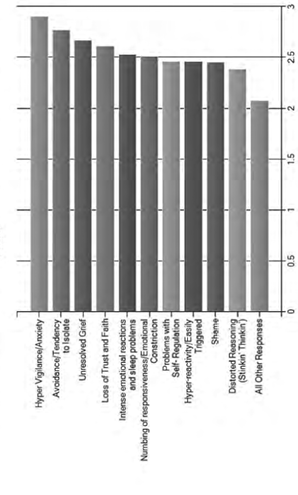

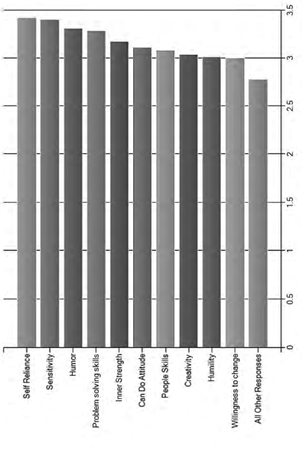

ACOA Survey: Positive and Negative

ACoA-related Qualities

Following is a graph representing the choices made in a survey of 333 self-identified ACoAs. The bars on this survey represent the top ten characteristics (both negative and positive) ACoAs identified with the most in order of identification. This survey represents a random sampling of people who elected to take it. The population was drawn from readers of my blog on Huffington Post, Recovery View, and from my own students and clients in recovery. The survey was entirely anonymous; no personal identification was recorded.