Chapter Two

The Shop

This here beef we having is like some corporate fight you’d read about in the Wall Street Journal, only this about our kind of business: rock cocaine.

—Ice

Anthony “Big Tony” Sherman is twenty-two, with a baby on the way. He’d served two years in an upstate prison for selling cocaine before coming home eight months ago. His first night back in Hempstead, he got his girlfriend pregnant.

“Doctor said it’s a boy,” Tony says. “Going to be my prince. He’ll be nothing but blessed.”

Tony is standing on the stoop of a run-down apartment building on Linden Place, which serves as the Crips’ clubhouse while doubling as the primary location from which they sell and stash crack, powder cocaine, and marijuana. He supervises the Shop—as the Crips’ main drug market is known—making sure the gang’s dealing crews throughout the area have enough coke and weed to meet the day’s demands. Shortly after sunrise, customers begin to arrive, anxious to see what kind of product the crew is slinging. All around them, students are walking to one of two schools near the Triangle: Hempstead High School and Evergreen Charter School. Most do their best to ignore the gangsters’ pitches. Others stop to cop, wanting to get lit before homeroom.

“Got that Luda!” one Crip shouts to a pair of junkies walking down the block.

“Come get that Notorious!” cries another gangster at an approaching car.

“Yeah, business going to be good today,” Tony says. “Weekend coming, so we opening a little early. Fiends be getting prepared. And I gots to get this money for the baby. Crib, diapers, clothes, all that stuff. My child going to be mad spoiled.”

The customers walk or drive up expectantly, ready to sample the Crips’ offerings. Tony’s sure the Luda crack vials and baggies will be big sellers, likely to surpass the Notorious viles and baggies as the crew’s most popular products. The night before, he’d passed out free samples to a couple of local junkies who serve as the crew’s product testers. They’d assured him the rocks had them good and lit—some of the best crack they’d ever procured in the neighborhood. They must have been telling the truth, because one of them, Charlie Bones, is among the first to walk up to the Crips shop this morning when it opens for business.

“Let me get that Luda, twenty hard,” Charlie says, ordering a $20 crack rock. “That shit’s the bomb.”

He hands over a wrinkled, yellow-tinged $20 bill to Tevin “Dice” Beckles, who’s handling tout duties for the Crips this morning. Touts promote the day’s drug selections, barking out product names and extolling their virtues to any potential customers within earshot. They also accept payment from each fiend and make sure all the cash is there.

“Damn nigga, you pee on this bill?” Dice says, holding up the $20 bill between two fingers like a dirty sock. “Shit is nasty.”

“Nah yo, that was my change at the store,” Charlie says, nodding toward the bodega up the street. “Ain’t nobody peed on it. Just old is all.”

Dice holds the bill up for closer inspection, gives it a sniff, and, seemingly satisfied it has not been pissed on, stuffs it in his pocket.

“Aight, but don’t be bringing them nasty bills over here no more,” Dice says.

Charlie, his hands beginning to tremble for want of a fix, grunts his affirmation; Dice directs him toward the side of an apartment building. Charlie waits there as Dice flashes a hand sign to Skinny Pete, a rail-thin seventeen-year-old handling runner duties today. Runners retrieve drugs from a drug crew’s hidden stash whenever an order is made and are usually the skinniest kids in their set because of all the exercise. Pete, seeing Dice’s hand sign, runs around the back of the building and returns with a baggie full of gumball-size crack rocks.

“This some high-quality raw right here,” Pete says, marveling at the product’s apparent quality.

Savant Sharpe, an eighteen-year-old aspiring rapper working as the crew’s lookout today, watches the street for any approaching cops or Bloods. Declaring the coast clear, he nods to Pete, who hands the baggie to Charlie. The fiend eyes it gratefully before sliding it into his sock and strolling off, whistling the opening notes to Marvin Gaye’s “Sexual Healing.”

This routine—with touts, runners, and lookouts all doing their part—will play itself out hundreds of times today on Long Island drug corners operated by Crips and Bloods. Thousands more crack and weed transactions will be made by the gangs’ sets across the country—part of a lucrative, wartime economic system still going strong nearly four decades after crack, a cheap, addictive form of cocaine, appeared in the United States.

“Another satisfied customer,” Tony says, watching Charlie walk off with his morning fix.

“We going to make bank of this batch,” says his deputy, Flex Butler.

Tony is the crew’s top street-level dealer and day-to-day manager. Flex, a jack-of-all-trades for the Crips, who handles everything from enforcement to package price negotiations, is ranked just below him in the gang’s hierarchy. Flex calls Tony on the phone or consults with him face-to-face in the gang’s clubhouse whenever a ruling on some pressing matter is needed. Tony, meanwhile, answers to the leader of the Hempstead Crips, a man named Tyrek Singleton. Depending on whom you ask, Tyrek is either the most ruthless, sadistic gangster in the New York metropolitan area or a gentleman hustler who runs his drug business more like Bill Gates than Scarface. “The man is a scary mothafucka,” Tony says. “And smart as hell, too.” Seeking insulation from his crew’s criminal activities, Tyrek typically stays off the streets. Tony is in constant contact with him, keeping him abreast of supply issues, daily profit margins, information about police presence in the area, and any fresh intelligence on the Bloods.

“If I hear they [the Bloods] about to make a move, any move, I tell Tyrek,” Tony says.

Tony sees himself as a businessman, partnered with Tyrek and other leaders in the Crips organization—Big Homies, as they’re known in Crips parlance—in a joint effort to recruit talent, maximize profits, and expand their customer base.

“We’re looking to market, sell, and profit off drugs the way any business would handle their product,” Tony says. “Only our product is illegal, so more precautions need to be taken. It’s all systematic and planned, all the positions and responsibilities and assignments. All of that’s part of our business strategy. It’s usually real smooth and quiet, because that’s the best environment for us to make bank. But now, we at war, man. Ain’t nothing quiet these days.”

The father-to-be often contemplates his own death, knowing it could come at any time now that full-scale armed conflict has broken out in the neighborhood. But he doesn’t worry much about the prospect of his son growing up without him.

“If I fall, my niggas going to take care of him like he’s their own. That’s how we do. We ain’t just an army. We ain’t just a business. We a family.”

Inside the “clubhouse” apartment where Tyrek, Tony, and the rest of the Crips spend much of their downtime, there are few hints that the space is a hub for crack dealing. The place is sparsely decorated, with a Notorious B.I.G. poster hanging in the living room beside a dartboard and Nerf basketball hoop. Wooden chairs and metal tables are scattered across the room for card playing and dominoes. Massive speakers and a sixty-inch plasma flat-screen television sit atop an entertainment center in the corner farthest from the door. The gangsters play a continuous stream of hip-hop on the speakers via Bluetooth setups on their smartphones, taking turns providing playlists. Rick Ross, Nas, Odd Future, Jay Z, 2Pac, Biggie, and Wu-Tang Clan are on heavy rotation. The TV is tuned to local news all day, so that the Crips can stay abreast of Hempstead’s latest shootings.

“Anybody gets shot around here, they put it on TV,” Flex says. “Nine times out of ten, we know the person. So we try and pay attention to it.”

“Sometimes, the stories be all about us,” Tony says.

There have been news reports of shootings and stabbings almost daily since the two sets began their war earlier this month. The police department’s gunfire recognition system, called ShotSpotter, registered so many gunshots in the area at one point that cops thought it might be malfunctioning. Today’s been quiet so far, but Tony believes that won’t be the case much longer.

“Sooner or later, they going to come for Dice,” Tony says.

Dice Beckles, the Crips tout, is widely thought to have shot Doc Reed, the high-ranking Bloods dealer, two weeks earlier. Tony believes a retaliatory shooting will be carried out by the Bloods at some point in the coming days, so he’s summoned several Big Homies to the clubhouse in order to talk strategy and weigh their options.

“Problem is, we don’t know when those niggas coming,” Tony tells them. “That means y’all got to be ready at all times. Do not leave home without a piece. And roll out in numbers, aight?”

The others nod. Some look no older than fifteen. Others are seventeen or eighteen and have either dropped out of high school or will before the school year is out. All wear sagging jeans with shirts from top-end designers and $200 high-tops. And each carries a blue handkerchief, a long-standing Crips tradition among the gang’s thousands of sets across the country.

“Aight,” says Dice, who’s wearing a bulletproof vest beneath his blue Yankees jersey in anticipation of a Bloods’ assassination attempt on his life. “But five-o be out there in force right now. How we handling that?”

“Just keep doing what you doing and don’t worry about the police,” Tony says. “They just making a show, peacocking and shit, but there ain’t nothing to worry about as long as you stay smart. They rolling through the hood more than usual because they expect shit to pop off at some point. But they a small-ass force, yo. Hempstead PD ain’t got the manpower to be up in our shit twenty-four/seven. And they ain’t got no undercovers they can get past us.”

By the police department’s own admission, Tony’s probably right. The force is undermanned and underfunded, the village still reeling from the Great Recession. It’s also true that the police have failed to infiltrate either the Hempstead Bloods or Crips with undercovers in the past. So as long as the gang’s members keep their mouths shut, Tony tells them, no major cases can be made.

“If you get picked up by five-o, just shut the fuck up, sit there, and wait for us to get you out,” Tony says. “Tyrek will take care of bail, lawyers, everything. You just carry that shit like a soldier.”

His address to the troops complete, Tony nods at Flex, who pulls out a garbage bag full of still-packaged burners—the hard-to-trace phones gang members often use to talk business—and dumps them onto a table.

“Everybody take one,” Flex says. “And use them shits wisely.”

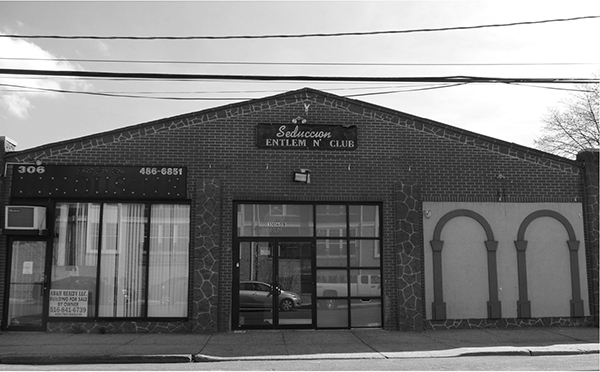

While the Crips wait on a retaliatory strike against Dice, the Bloods brain trust plots one. The leader of the local Bloods set, Michael “Ice” Williams, twenty-four, has summoned Steed Wallace, Doc Reed, Lamar Crawford, and several other members to Seduccion, a Hempstead strip club used by the gang as an occasional meeting spot.

Sipping on Hennessy at a table beside the stage, Ice tells his men they’ll exact revenge for Doc’s shooting by going after Dice, but not for another four nights.

“Today’s Friday, and the cops probably going to be beefing up patrols tonight and all weekend,” Ice says. “Come Monday, most likely they’ll scale shit back. Tuesday, they’ll be even less of them. That’s the night we ride out.”

Doc lobbies for an assignment as triggerman for the mission, since he’s familiar with Dice’s daily routine and wants to avenge his own shooting. In the Triangle, if an enemy gang member tries to kill you, the only acceptable response is to return the favor.

The now-defunct Seduccion gentleman’s club was used by the Bloods as a meeting spot for strategy sessions during the gang war.

Kevin Deutsch

“Dice usually be smoking weed on the stoop of his cousin’s house after school,” Doc says. “We could just drive past and take that nigga out real easy.”

Steed says he’s obtained a semiautomatic TEC-9 for the drive-by from a Bloods associate—someone who works for the gang but is not yet an official member—per Ice’s orders. As far as Steed knows, the gun is unregistered and untraceable. The TEC-9 has recently become the Bloods’ go-to weapon for drive-by shootings, mostly because they’re cheap and plentiful on the black market. They also hold a thirty-two-bullet cartridge, increasing the chances that at least one round will strike an intended target, however inept the triggerman.

“You ever handled a semiauto?” Steed asks Doc. “Ain’t no fucking toy.”

“Ain’t no piece I can’t handle,” Doc says.

Steed looks to Ice, who nods in approval of the plan, making it official. The Bloods leader then turns to his protégé, Lamar Crawford, whose main job these days is running the Bloods’ prostitution racket.

Ice tells Lamar that he wants him to “handle the management end” of the drive-by. “You and Doc together on this. You need another soldier or some other issue come up, let Steed know,” Ice says.

A broad-shouldered nineteen-year-old who recently graduated from Hempstead High School, Lamar is considered one of the set’s smartest, most capable members. He’d handled corner dealing, lookout, and runner duties before taking over the crew’s burgeoning prostitution business and is now being groomed to take on more responsibility. Ice has made Lamar’s professional development a personal project of sorts, gradually moving him up in the gang’s hierarchy in accordance with his annual progress in school. As a freshman, he’d been a lowly messenger. Now, a few weeks after earning a diploma, he’s been chosen to take part in an important assassination mission, which will have repercussions for months after the shots ring out.

“You ready to step up?” Ice says.

“Mos def,” says Lamar.

Once their meeting ends, the Bloods watch as several dancers gyrate onstage, inviting customers to slide bills into their G-strings. The young women focus nearly all their attention on Ice, like he’s some kind of celebrity. Around here, according to Hempstead residents and fellow gang members, he is. No gangland figure in the neighborhood, with the possible exception of Tyrek Singleton, commands more admiration or fear. Ice is thought to be one of the wealthiest, most powerful men in the community. Unlike most of the local Bloods and Crips, Ice attended college and earned a bachelor’s degree in accounting. His own education was one of the reasons he’d made a point of ushering Lamar up through the ranks as he advanced in school.

“Intelligence is important, education is important, putting your mind to good use is important,” Ice says. “That’s why I’m bringing Lamar along . . . he’s got book smarts to go with street smarts.”

Ice speaks often of authors he’s read, from Frederick Douglass and Richard Wright to Sun Tzu and Machiavelli. He’d had plenty of time to absorb the classics while serving five years in prison for selling crack. Despite having a degree, Ice’s rap sheet is as long as those of the high-school dropouts who populate most of Hempstead’s drug corners. Like many Bloods and Crips, he’d also survived a gunshot wound—a bullet to his left ankle that left him with a permanent limp.

“I ain’t no saint and I ain’t no genius, but I’ll sometimes give books to the younger niggas who show potential, talk to them about philosophy, history, everything,” Ice says. “Most of them won’t finish high school, because they like making money out here too much. I respect that, too. That’s capitalism. But I try to educate them when I can.”

Ice says his pursuit of an education in accounting stemmed from his long-running interest in business and a natural acumen for deal making. After graduation, he’d languished in a low-level job with a financial firm in New Jersey. He moved on to a similar job at a more prestigious company in Manhattan, but his bosses rarely let him do any real accounting work, instead turning him into a glorified gopher who fetched their coffee in between menial assignments.

“I believe my skin color held me back when I tried to pursue a career in accounting and finance,” Ice says. “I was not allowed to work at the level I was capable of; because I’m black, I was seen as less capable.”

Eventually, Ice was laid off. Broke and jobless, he returned to the Park Lake apartments on MLK where he’d grown up, and where his mother still lived. He quickly fell back in with his old gang, working his way up in the Bloods chain of command and eventually taking charge of the Hempstead set.

“I knew how to run a business, and this ain’t so different, really,” he says. “This here beef we having [with the Crips] is like some corporate fight you’d read about in the Wall Street Journal, only this about our kind of business: rock cocaine.”

For street dealers, there’s still no more profitable drug than crack. A user can smoke as much of it as he wants, as opposed to powder, which limits him to the amount he’s able to inhale before his nose goes numb or becomes too runny to continue. It takes a few minutes to feel the rush from powder cocaine, but crack vapor floods a user’s lungs as soon as he inhales, delivering a quick, walloping high. Crack smokers describe the feeling as more intense than an orgasm, a wave of pleasure coursing through their entire bodies. In addition to being stronger than its powder alternative, crack is far cheaper—as little as $10 for a smokable rock, compared with $30 for a gram of powder.

Of course, crack has its drawbacks for the user. The drug’s euphoric effects last only a few minutes, meaning a continuous supply is needed to keep the ride going. Even at $10 a rock, costs can add up quickly. If a user doesn’t sustain his high, he can expect a wave of depression, anxiety, and irritability to wash over him. His cure, blessedly, is always just $10 away. And as he falls into an endless cycle of addiction, his dealer—often a Bloods or Crips member—gains a customer who can’t live without his product.

“What you have here is a situation where both crews have a great product, and neither is open to being bought out,” Ice says. “What you think’s going to happen if neither side wants to give in? What happens is, things get messy. And that’s what you seeing now. A whole lot of mess.”

As the gang war carries over into February, police are seemingly powerless to stop it. Part of the blame lies in their inability to infiltrate either crew with undercover officers. Aside from developing an informant—a near-impossible task in the Triangle, with snitching punishable by death—an undercover operation is the only way the gangs’ leaders can be taken off the streets in one fell swoop.

“It’s a very difficult thing to do,” says Hempstead chief of police Michael McGowan. “They’ve been successful thus far in keeping [undercovers] out.”

The department’s failure to infiltrate the crews isn’t for lack of trying. At every house party where Bloods or Crips might be expected to congregate, police have tried to get undercovers inside. Each time, they’ve been thwarted.

“We know what cops look like, no matter what kind of gangster shit they try to dress up in,” says Lamar Crawford. “A pig’s a pig.”

Another challenge facing law enforcement is the fact that there’s no single agency with total responsibility for battling Hempstead’s gangs. The Nassau County Police Department, the county’s biggest and best-funded law enforcement agency, has its own team of veteran gang investigators. But Hempstead is technically outside their jurisdiction, so while Nassau takes the lead on homicide investigations in the village, most other cases are assigned to the smaller, lesser-funded municipal force.

“We do what we can for them,” says one Nassau detective involved in gang investigations. “But we have several dozen gangs we’re dealing with across the county. It’s a matter of priorities for us. There are only so many resources.”

Both the Bloods and Crips exploited law enforcement’s weaknesses in the years before the Triangle war, seeing just a handful of members arrested on major felony charges. As a result, once war broke out, both crews felt little need to scale back their drug enterprises or de-escalate the conflict.

“Way we see it, they ain’t shit,” Ice says, summing up his crew’s opinion of the police. “Even if they do get their shit together long enough to make a case, ain’t nobody out here going to talk to five-o or testify against any of us. That’s just the code. That’s law. That’s the way it is . . . way it always will be.”

Ice’s characterization will prove accurate two nights later, when the protracted crackle of automatic gunfire echoes through the neighborhood just after eleven p.m. One explosive burst of ammunition. Then a second and third. Fifteen to twenty shots in all. Within minutes, police cars and ambulances are screeching up Linden Avenue, sirens blaring and lights flashing.

Near the stoop of a Crips stash house, a blood-soaked, Air Jordan sneaker lay in the road. Ten feet away lay a baby-faced Crips member, “Little James” Carter, with a quarter-size hole in his forehead. His other sneaker rests beside him in a rapidly expanding pool of blood. After the medical examiner takes James’s body away, one of his fellow Crips, Savant Sharpe, picks up the pricey high-tops. Next day on the stoop, he’s wearing them.

“No shame in this game,” Savant says. “Besides, they too fresh to go in the garbage.”

The investigation into James’s murder follows a familiar pattern: Cops interview everyone in the area at the time of the killing; all claim to have seen nothing. As in most neighborhoods plagued by gang violence, the residents of Hempstead typically don’t talk to police about gang shootings for fear they’ll be the next targets. The “snitches get stitches” rule is taken seriously here, and those who break it can expect swift retribution, residents say.

“Why should I tell the cops anything?” says Donna Crawford, Lamar Crawford’s aunt, who, after losing two sons to gang violence, refuses to talk to police about any crimes perpetrated by Bloods or Crips in the Triangle. “What are they going to do for me? Witness protection? Fly me to Hawaii? Walk my son home from school every day? I don’t think so. I’ll have to live here long after they’re gone.”

Donna’s fears are shared by most people in the Triangle, who know police can’t protect them or their families forever. Despite the neighborhood’s code of silence, detectives investigating James’s murder do everything in their power to catch his killer. They interview dozens of residents and gang members, pore over hundreds of hours of surveillance footage from area businesses, and prod street units to make a half-dozen or so drug arrests along MLK and the Triangle. The sweep, they hope, will lead someone to identify James’s killer in exchange for a deal with prosecutors promising leniency.

But not one of the collared gangsters will talk.

“They think we’re stupid, but we know Miranda,” Steed says shortly after Ice posts his bail. He’d been charged with possession of cocaine, even though, he says, police found no drugs on him.

“That case is good as gone,” he tells Ice. “They was just rounding niggas up and making up charges. No chance that shit sticks. We all know our rights and asked for lawyers.”

Neither Steed nor any other gang members arrested in the wake of James’s shooting prove useful to detectives, so they pursue other avenues. One of their most promising leads is a call made by an anonymous woman to a police tip line, claiming she’d overheard a Bloods member bragging he was about to “go shoot a Crip” the night of James’s murder. The tipster even gave the plate number for a car she’d seen the man drive off in shortly before the shooting. Detectives comb through a Department of Motor Vehicles database and quickly identify the car, its registered owner, and his apartment number in a Hempstead project.

“Bingo,” says Hempstead detective Mark Delahunt when the car owner’s address pops up on his computer screen. “This has got to be our guy.”

They rush to the man’s apartment, believing they might be about to solve the case. But when they knock on the door and announce their presence, a hunchbacked old man with greasy gray hair and track marks on both arms opens it. He invites the detectives in and excuses himself to retrieve his dentures. An elderly woman emerges from a rear bedroom in her nightgown, offering the detectives coffee. After a few minutes of questioning, they determine that the old man’s longtime girlfriend—a known crack addict, upset with him for taking back his nightie-clad ex—had exacted revenge by fingering him for James’s shooting.

“Hell hath no fury like a crackhead scorned,” Delahunt says after they leave the apartment. “This town is fucking unbelievable.”

Three days later, a wake is held for Little James. His casket is ivory white and narrow, just wide enough to fit his body inside its purple velvet walls. He looks cramped in the open casket, but peaceful. A navy blue suit and oversize white dress shirt hide his chest wound. One mourner whispers that the bullet that killed him remains trapped inside his heart’s left ventricle. Some Bloods snap pictures of James’s corpse and post them on Facebook, accompanied by threats against the Crips.

James’s little brother, Horace, tries to wake him up by prying open his eyes. When that doesn’t work, he lowers his head and cries.

“Why I can’t wake you?” the boy mumbles into the coffin. “Please wake up, James.”

Tyrek doesn’t attend the funeral, believing—correctly, it turns out—that police will be in attendance and leaning on people to snitch. But the day after James is buried, Tyrek makes his way to the graveyard to pay his respects. Standing over the mound of fresh dirt, he smokes one Newport after another, whispering prayers for James’s soul.

“You a soldier, J, you a soldier,” says Tyrek. “Please, God, let him be with you.”

Tyrek looks exhausted, having slept just an hour or two since the shooting. He appears to have lost weight, too, his face gaunt and oily. He becomes defensive when asked if he feels any guilt for James’s death—whether his murder is what’s keeping him awake at night.

“I ain’t the one who put the bullet in him,” Tyrek says. “I didn’t force him to work the corner. He asked me for work, so I put him to work. He was a good kid. But he’d grown up fast, too, so he wasn’t really a kid no more, you know? He had drive . . . wanted to work, wanted to make some money so he could buy his own things and help out his mom and brothers.”

From there, Tyrek offers a broader defense of his illicit activities in Hempstead, arguing they’re the heart of the village’s economic engine.

“I hear whispers in the hood, people saying I brought war to their blocks over a couple of corners. But the truth is, ninety-nine percent of these niggas around here would be jobless and making no money if I didn’t do what I do in this community. Shit, who you think paid for church services, for the casket, for this plot right here?”

He points a finger at his own chest, tapping it emphatically.

“My money must not stink, ’cause ain’t nobody turning it down.”

After James’s murder, Bloods involved in his shooting take precautions to try and ensure they’re not arrested by cops or targeted by Crips. Doc Reed, the presumed triggerman, stays off the streets for six weeks. The police are looking to interview him, he knows, visiting his mother’s house every day to ask whether he’s turned up. So for the time being, he’s living at the apartment of a Bloods associate in Brooklyn, along with Lamar, who’d overseen the drive-by mission. Doc and Lamar insist to their host that their intended target had been Dice Beckles, the Crip believed to have shot Doc in January.

“Nobody likes to see that type of collateral damage,” Doc says of James’s death. “But he chose sides; he wasn’t there by accident. Little nigga been running with Tyrek’s crew long as I can remember. You put yourself in that position, even if you a shorty, you know you ain’t going to be immune. If you in it, you in it. Dice was the one who supposed to get hit. But he a little bitch, so he hit the deck when the shooting started. A soldier would’ve come out and met that shit head-on, instead of letting that young nigga die. Way I see it, James done fell because his own boy Dice was a fool. People on the block mad at our crew for killing the wrong Crip? Nah, that ain’t logical.”

Then Doc crystallizes the Bloods’ mentality regarding the gang war.

“They started this shit, they can end it,” he says of the Crips. “All they got to do is give up them corners in the Triangle.”