Chapter Nine

True Believers

And I’ll keep praying for these gangsters on the corners, the ones who can still be saved, until they put me in the ground.

—Marsha Ricks

The sinister plots hatched by one gang against the other don’t stop. But neither do Reverend Lyons and his prayer marchers. They return to the Triangle every Friday just before midnight, always with the goal of preventing retaliatory attacks. There are whispers the group may themselves be targeted for sticking their noses in the business of warring gangs. In fact, the risks they face seem to multiply by the week. Savant Sharpe, convinced the marchers are police informants, has promised to hunt them down and kill them if he’s proven right. Doc, believing Reverend Lyons is more sympathetic to the Crips’ plight than his own gang’s, says he’ll treat the reverend as a combatant should a gun battle break out while he’s in Bloods territory.

Still, the marchers are not dissuaded. “There might be another person shot at any time,” Lyons says one muggy Friday in August. “But we pray not.”

As they march up Linden Place, plumes of marijuana smoke drift from a dozen open windows. Dealers perched on stoops scurry up to cars or pedestrians who stop to buy crack or weed. Glassy-eyed pipeheads stumble nervously through the Triangle, drawn like moths to the glow of dealer’s smartphones.

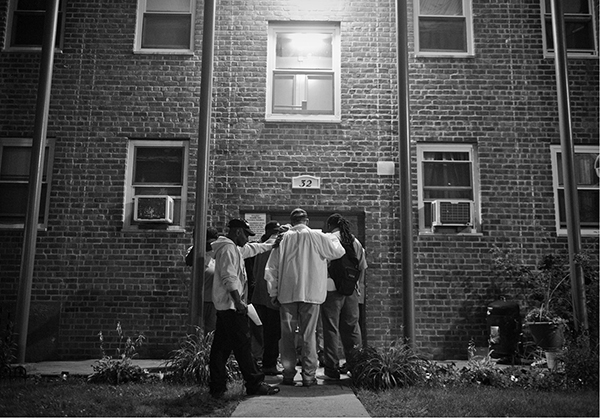

The marchers pray with local Bloods outside the Park Lake apartments, shown here. There are whispers the group may themselves be targeted for sticking their noses in the business of warring gangs. Savant Sharpe, convinced the marchers are police informants, has promised to hunt them down and kill them if he’s proven right.

Steve Pfost

The Crips slinging on the stoops are immaculately dressed, decked out in sagging designer pants, custom-made baseball jerseys, and the newest LeBrons, Air Jordans, and Dwyane Wades. Platinum chains adorn their necks. Thousand-dollar watches circle their wrists. Tony—who’s managing the main Crips shop tonight after a few weeks of staying off the street, per Tyrek’s orders—wears diamond earrings thick enough to put his newborn son through college. He’s the first of the Crips to notice Lyons coming toward their stoops and nods in the reverend’s direction.

This time, none of them wear red.

“We listened,” Lyons says.

“Appreciate that,” says Tony.

“How y’all been since last time?”

“We aight. You know how it is. Holding it down.”

“Glad to see everyone’s safe tonight,” Lyons says. “Now, you all know what brings us out here?”

“Yeah,” says Bolo, fresh off his stash-house sequester and now an official Crips soldier. “You trying to bring Jesus up in our crew.”

The Crips all laugh, as do the marchers. The older men can remember hanging with the fathers and uncles of some of these boys back in the day, drinking beers and chasing girls with them in Hempstead. Most are dead now, cut down by bullets or blades following senseless arguments over gang colors, money, women, or drugs.

The marchers join hands and pray with several Crips members outside the gang’s headquarters in the Triangle.

Steve Pfost

After a while, all the ancient beefs bleed together in the Triangle, making it hard to remember which slight cost which man his life. All that matters to the marchers now is saving this new generation of hustlers, making sure they escape the fates of their elders.

“In a way, I guess we do want to bring Jesus up in here,” says one of the marchers, Calvin Bishop. “But mostly, we just want to pray for you all to be safe and healthy, and ask God to look out for you all and your families, so that he brings you and the people you care about blessings and peace.”

“Ain’t nothing wrong with some blessings,” says Flex Butler. “Blessings always good.”

“Would you gentlemen let us pray with you for a moment, then, so that we can seek those blessings?” Lyons asks.

The gangsters ponder his request, silently calculating the potential impact of such a prayer. Would it scare off their customers? Would it be interpreted as a sign of weakness by the Bloods? Were these “old-ass” marchers—however harmless they appeared—actually working for the police, as Savant suspects?

“We’re not here to interfere,” Lyons says, trying his best to close the deal. “We just want to praise God and ask for his blessings to keep everyone safe tonight.”

There’s a long pause, punctuated by the sound of a woman crying in the distance.

“Yeah,” Tony says. “A little help from on high can’t hurt no one around here.”

“That’s the truth, son,” says Lyons.

“So let’s do it up,” Tony says, his gold teeth twinkling in the porch light.

Each marcher takes the hand of the Crip closest to him. The men circle up, bow their heads, and close their eyes. Lyons breathes in deeply, focusing, wanting badly to reach these boys tonight.

“Dear God,” he says, his voice loud and rhythmic as it carries through the Triangle. “We come to you tonight seeking your wisdom and protection. We ask that you give these young men quarter from the pain and violence and suffering on this block, and that you bless them with your everlasting goodwill and favor.”

Some of the pipeheads turn to see where the churchly pleas are coming from, wandering toward the prayer circle as Lyons continues. “You, Lord, are the truth and the way. We are here tonight to praise you, to serve you by spreading your Word, and ask you to help heal this struggling neighborhood. Lord, we ask that you look after these young men and keep them safe from harm, that you help heal all wounds in the Village of Hempstead.”

“Amen!” the marchers shout.

“We ask that you look after these young men and their families,” the reverend continues, “that you shield them from the violence and addiction and troubles that have plagued this community, that you guide them through these streets unscathed and strong.”

“Amen!”

“We ask you, Lord, to lead these young men through the darkness and into the light, where they will be safe under your watch. We ask that you carry them toward bright futures and happiness and safety—that you ease them through whatever difficulties they may encounter until they reach calmer seas. Amen.”

“Amen!”

Their prayer complete, the Crips and marchers exchange handshakes and first bumps. Others embrace. The prayer, it seems, has left them all feeling good.

“Dang, I done thought I was in church for a minute there,” Flex says. “Forgot what it’s like to be praying. Been a while.”

“Well, we’ll help you remember,” Bishop says. “A little prayer can never hurt in the Triangle.”

“Word,” Flex says.

“Be safe,” says Lyons. “We’ll keep praying for y’all.”

“Y’all stay safe, too,” Tony says. “For real. Ain’t no joke out here.”

Once the gangsters are out of earshot, Lyons deems the encounter an unqualified success.

“We’re starting to reach them,” he says. “They’re listening. That’s a big step.”

The reverend calls his gang intervention program Boots on the Ground, a military term he chose because, like the hustlers whose lives he’s trying to save, Lyons views his work as a daily battle, a war fought for the souls of young men.

“You don’t win wars by fighting from a distance; you win them by getting in close,” Lyons says as he leads his marchers toward the next drug corner. “You can pray for change in a place, but there’s something about being present in that place, and actually being an agent of the change you’re praying for, that allows you to make a greater impact. Get in close, and change is possible. At least, that’s what we hope.”

As the activists march down Linden Avenue, empty crack vials lay scattered every few feet. Baggies once packed with powder cocaine or crack rocks litter the pavement. An emaciated pipehead wearing a tattered Yankees cap walks alongside the marchers, picking up discarded baggies, holding them up toward streetlights in search of leftovers.

“Got-damn,” he says each time he finds one empty.

Calvin Bishop walks toward the pipehead, who’s so engrossed in his search for leftover crack he doesn’t notice the marchers approaching. Bishop is about to greet him when the man looks up with panic in his eyes.

“Get back!” he yells, reaching into his pocket and coming out with a kitchen knife. It’s stained with what looks like peanut butter and a smattering of jelly. Still, it’s sharp at the point—sharp enough, by the look of it, to do some damage.

“We don’t mean any harm,” Bishop says, his voice soft and steady as he looks into the pipehead’s eyes. A former crack addict himself who got clean after embracing Christianity, Bishop understands the pipehead’s fear and paranoia all too well. “We apologize for disturbing you, sir, sincerely. We were just going to ask if you might be willing to pray with us for a moment.”

The man purses his lips, eyes Bishop warily, and puts the knife back in his pocket.

“Y’all going to get yourselves killed walking round here like a bunch of got-damned Boy Scouts,” he says. “What you think, you in Disneyland or sumpin’?”

The pipehead walks off to continue his lonely quest through the Triangle, scanning the ground in search of that overlooked rock some fiend always leaves behind—a little chunk of salvation to steel him against another night in a war zone.

“Crack,” says Bishop, watching him go. “Turns them into zombies. I wish we could save them all from this kind of life, the way I was saved through the power of prayer. But there’s just too many.”

From her living room window, Marsha Ricks watches the marchers stride past. Her one-story, bungalow-style home sits at the midway point between the Bloods’ and Crips’ territories, having served as the unofficial demarcation line—“the DMZ,” as she calls it—in more peaceful days. In the past three years, five stray bullets have struck her house, she says. Still, she clings to the hope that things will get better.

“If there’s one thing I know about these young men in the gangs, it’s that they can’t shoot straight,” says Ricks, eighty-two, who has lived in Hempstead for more than sixty years. “Lord, they might as well be blind the way they aim. But you never know. The violence could stop one of these days. Things could get better.”

Because of errant gunfire, Ricks says she long ago stopped watching TV in her living room at night. That room has the most windows.

“I won’t even sit in there to do my crossword. If a bullet comes through the window or tears through the wall, I could die right there in my chair. So I watch TV and do my puzzles in the back bedroom. No windows in there. It’s much safer.”

Ricks says the neighborhood was once peaceful, back before crack steamrolled its way through Hempstead in the 1980s, coinciding with a recession. She remembers ice-cream trucks coming down her block five times a day, Girl Scout troops going door to door, selling cookies.

“When I was raising my son, this was a wonderful place. The yards were green and well-kept, trees lined the street, and there was no filth in the parks. I loved it here, and my husband and child loved it. In the 1970s, even in the early ’80s, I would let him play out in the street, ride his bicycle, or go to the park to play basketball. I didn’t worry. There were some gangs, but they didn’t go around advertising it. They kept to themselves, moved in their own little world, mostly, and we had nice lives out here. It was safe, clean. People looked out for each other.

“One day, I remember, I started to see dealers on the corners late at night, selling crack. At that time, I didn’t know what it was. But I learned real fast, because everybody started talking about it. My friends’ kids were walking around like zombies from it, or going to jail for selling it. They said crack was an epidemic, and it really was. But the police didn’t do much to stop it. In fact, they seemed to allow the dealers to run free here, so as to keep them out of the white neighborhoods and the nicer parts of Hempstead. Now, you can call that a conspiracy theory, but around here, it was just seen as fact. There was no other way to understand how it could be happening.”

One day, Ricks’s fed-up husband, Miles, went to tell off the dealers who’d turned his once-attractive street into a vial-strewn drug market. They got in the old man’s face, pulled out their guns, and scared him so badly he suffered a fatal heart attack right there in the street.

“Crack stole my husband from me, as far as I’m concerned. And in the years after he passed, it went away in other communities, but not here. You can still buy as much of it as your heart desires, right outside my house.”

Ricks says her son, a forty-six-year-old medical student in New Jersey who gave up teaching elementary school math to pursue a career in emergency medicine, is constantly urging her to move—to finally leave behind the pain she endures every time she passes the spot where her husband of forty-six years fell dead.

“But every time I think I can say yes to leaving here and going to live out near my son, I think about my memories of this house, and I say, ‘Why should I be the one who has to leave? Why don’t these killers and drug dealers and dope fiends leave instead of me?’ Now, I know that’s not likely to happen, but I’m an optimist. Always have been, and I guess I can’t change. But I remember the old days, watching kids playing out there, me and my husband sitting on the porch drinking sodas, waving to our friends driving past. I do believe my grandkids might come back and see the neighborhood like that again one day, after I’m gone. That’s one of the things I pray for—that God will take the cancer out of our neighborhood. And I’ll keep praying for these gangsters on the corners, the ones who can still be saved, until they put me in the ground.”

Long before the Bloods and Crips moved in—before the crack explosion, semiautomatic weapons, and joblessness threatened to destroy the neighborhood—Hempstead was a sleepy, idyllic little village with a seemingly bright future. It began as a meeting place for farmers and traders looking to buy goods and exchange information, a hub of commerce for nineteenth-century Long Islanders.

In the following century, a series of ambitious road-construction projects linked New York City to Long Island, allowing thousands of city residents to visit, and later, to move permanently to Hempstead. The village’s population increased more than tenfold between 1870 and 1940, from 2,316 to 20,856, according to Sarah Garland’s Gangs in Garden City. In one of the earliest examples of white flight, newcomers transformed Hempstead into a bustling modern suburb—one of the country’s first—lined with cookie-cutter homes and perfectly manicured lawns.

Long Island neighborhoods with quality housing grew rapidly in the late 1940s and ’50s, part of a national trend that saw city residents moving to the suburbs in droves following World War II. Hempstead’s rapid expansion created demand for more stores and commercial areas, which went up with astonishing speed alongside giant parking lots for customers, come to town for a day of spending.

The village continued to grow throughout the 1960s, thanks to an influx of immigrants, who’d found economic success in the city and wanted a safer, quieter place to raise their families. Hempstead became known as The Hub due to its history as a commercial center, and the opening of its own Long Island Rail Road station. It was also a retail hub with scores of shops, including the popular Abraham & Straus (A & S) department store. People traveled from all over Long Island to shop there, injecting a flood of new tax money into municipal coffers.

While white flight drove much of Long Island’s population boom, scores of minorities flocked there as well, moving to Nassau and Suffolk at more than twice the rate of whites during the 1950s, according to Garland’s account. Even as the image of Long Island as an ultrasafe, all-white, suburban utopia took root in the American imagination during the ’60s, African Americans were relocating there in huge numbers.

“It’s a part of Long Island history that isn’t often told, but there was truly a great migration of African-American families like mine in the 1950s and ’60s,” says Ricks. “We came here looking for the same things—safe streets, good schools, peace and quiet—that whites did.”

Blacks often encountered an even deeper discrimination in Long Island’s suburbs than they’d experienced in cities. With America embroiled in contentious debates over civil rights, and with racism rampant in many communities, discriminatory housing practices remained common through the 1960s and ’70s in Hempstead. Banks routinely refused home loans to blacks, and when minority families did find financing, they were often steered to predominantly black neighborhoods. Meanwhile, in mixed neighborhoods, whites couldn’t get away soon enough. They fled Hempstead for whiter communities in other parts of Nassau, Suffolk, and Queens.

As whites moved on, Hempstead’s aging bungalow-style homes and decaying apartment buildings drew black tenants hoping for their own piece of the suburban dream. They quickly became the majority. And by 1990, the village was nearly all black—a stark example of the suburban segregation already under way in suburbs of Chicago, Kansas City, Fort Lauderdale, St. Louis, West Palm Beach, and dozens of other fast-growing metropolitan areas.

It was during this period that Bloods and Crips found a home in Hempstead. Their arrival coincided with the flight of many village retailers, including A & S, who were taking a beating from malls and big-box stores. Some businesses were abandoned, while arsonists torched others in insurance scams. Crime rose, due in part to the newly arrived gangs and the crack, which became the foundation of their economy.

By the mid-1990s, Hempstead was a shell of its former self. Black families who’d moved there in search of the good life ended up living in the same slum-like conditions they’d tried to escape. Still, Ricks and many hardworking families in her neighborhood believe it can still be saved.

“Even the Triangle, I know, can be redeemed,” says Ricks.

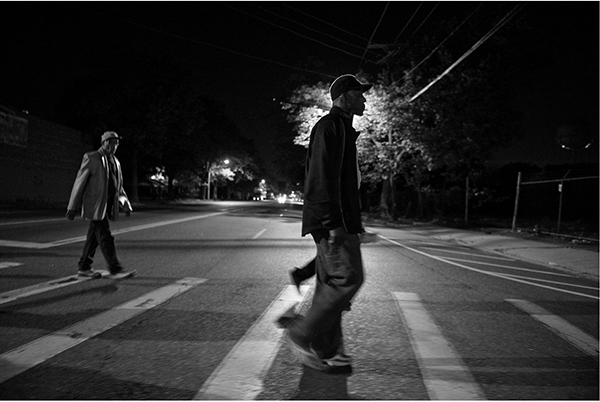

Bloods members and prayer marchers cross a street in Hempstead during the gang war. A few blocks away, the Crips are gathered in their clubhouse, plotting a drive-by.

Steve Pfost

Despite all available evidence, folks in the Triangle have always found a way to believe that better times lay ahead, she says. They believed even as more and more homes were abandoned and occupied by pipeheads and dealers. They believed even as pimps and prostitutes became neighborhood staples. They believed even as the Crips and Bloods arrived in force, set up major drug markets, and unleashed a plague of gun violence. And they believed even as the Triangle became exactly what they’d moved there to escape: a place brimming with poverty, drugs, and death, a kind of free-fire zone where a kid had as good a chance of catching a stray bullet as he did in parts of Syria or Afghanistan.

“We do believe in a better day, because good can outlast evil,” Ricks says. “That’s what some of these gangsters are. Plain old evil.”

Young men like Tyrek, Tony, Ice, and Steed represent everything the “true believers,” as Ricks calls Hempstead’s good citizens, stand against. The gangsters are among tens of thousands of Bloods and Crips living in the poorest swaths of America’s cities and suburbs, mostly uneducated, mostly parentless, raising themselves in packs off the proceeds of petty crimes that later escalate to organized trafficking and violent felonies. In a way, their fates were decided long before they put on gang colors.

“Basically, there ain’t no direction I could see going in other than joining [a gang],” says Tyrek. “It’s like, natural and shit. That’s the path you expected to take. That’s the path you need to take around here, unless you want to be rolling around by yourself and not have no back. It’s how you get a family.”

Hempstead’s true believers have long tried to change the mentality of these young men, but violence and gang activity have increased nonetheless. Gang-related arrests more than tripled between 1995 and 2001 in Nassau alone, according to Garland’s account. In the handful of predominantly minority communities stretching across central Nassau—an area known to police as “the corridor”—more than 300 people have been killed by gun violence over the past fourteen years. More than 80 of those were killed in disputes linked to Bloods or Crips sets and their assorted beefs.4

4 This information is drawn from the author’s analysis of police and court records, as well as interviews.

Much of the region’s gang violence in 2012, even in Long Island and New York City neighborhoods far from Hempstead, can be traced back to the Triangle war. In ways both seen and unseen, this single Bloods–Crips conflict has sent ripples through the region’s underworld establishment, heightening tensions among other sets, pressuring them to retaliate for shootings in Hempstead, and forcing them to lend resources to the Triangle war effort.

“The battle over turf in the Triangle and MLK is at the heart of everything,” says Delahunt. “It’s connected to many of the shootings in Freeport, Roosevelt, Uniondale, Brooklyn, Queens, Harlem . . . pretty much any neighborhood around here where the Crips and Bloods have a presence. The Triangle’s the epicenter, and it radiates out to those other communities in the corridor and out to New York City. No shooting, no drive-by happens in a vacuum. There are repercussions and different moves made in response to every one of them in different neighborhoods, involving different sets and crews.

“The gang world seems simple—he kills my boy, I kill him—but nothing’s simple. It’s a very tangled web of relationships, of beefs that sometimes go back years and involve all kinds of different gangsters, their associates, their girlfriends, their suppliers, and other hustlers. The deeper you dig, the more craziness you see. Shit, if you dig deep enough, you’ll even see the Bloods-Crips connection to the cartels.”