On 21 June 1942 Gen Erwin Rommel issued an Order of the Day to the men under his command:

Soldiers!

The great battle in the Marmarica has been crowned by your quick conquest of Tobruk.

We have taken in all over 45,000 prisoners and destroyed or captured more than 1,000 armoured fighting vehicles and nearly 400 guns. During your long hard struggle of the last four weeks, you have, through your incomparable courage and tenacity, dealt the enemy blow upon blow. Your spirit of attack has cost him the core of his field army, which was standing poised for an offensive. Above all, he has lost his powerful armour.

My special congratulations to officers and men for this superb achievement.

Soldiers of the Panzer Army Afrika!

Now for the complete destruction of the enemy. We will not rest until we have shattered the last remnants of the British Eighth Army. During the days to come, I shall call on you for one more great effort to bring us to this final goal.

ROMMEL

The Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was in Washington when he learned of the fall of Tobruk. His trip to the United States had been intended as an opportunity to build on his relationship with President Franklin D. Roosevelt; instead Churchill had to confront Britain’s gravest crisis since the black days of the Battle of Britain two years earlier. ‘Into the Middle East for three years the British Empire had poured every man, gun and tank it could spare,’ wrote the noted Australian war correspondent Alan Moorehead, who had first arrived in Cairo in June 1940. ‘Here alone the British had a front against the enemy. The loss of Egypt would precipitate a chain of misfortunes almost too disastrous to contemplate.’

But contemplate them Moorehead did, as Churchill did too. If Rommel’s Afrika Korps conquered Egypt, then Britain would lose Malta and with it control of the Mediterranean. The Suez Canal would also fall into German hands, imperilling Palestine and Syria and, in the longer term, India and the Soviet Union.

As the British quailed, Rommel pushed east, reaching Sidi Barrani by the evening of 24 June and the next day advancing to within forty miles of Mersa Matruh. On the last day of the month Rommel approached the El Alamein line, just 65 miles west of Egypt’s second city of Alexandria. The British fleet had already fled the coastal city and all officers received orders to rejoin their units immediately. Meanwhile in Cairo, recalled Moorehead, ‘the streets were jammed with cars that had evacuated from Alexandria and … the British consulate was besieged with people seeking visas to Palestine. The eastbound Palestine trains were jammed. A thin mist of smoke hung over the British embassy by the Nile and over the sprawling blocks of GHQ – huge quantities of secret documents were being burnt.’

In Cairo at this time was a young Scottish major named David Stirling. While Rommel had been overrunning Tobruk, Stirling and a handful of men from L Detachment, Special Air Service Brigade, were busy attacking aircraft and shipping in the Benghazi–Berca–Benina area, the latter being the Germans’ chief repair base for their aircraft, approximately 700 miles west of Alexandria.

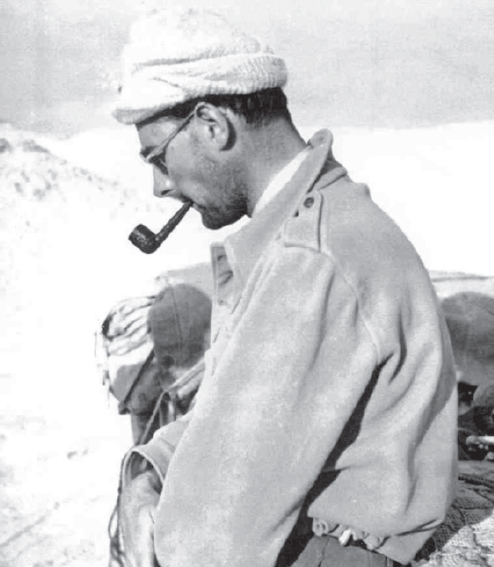

The Germans nicknamed Stirling ‘The Phantom Major’, such was his ability to ghost on to airfields, wreak havoc and then vanish without a trace.

The Afrika Korps’ arrival in the Western Desert in early 1941 made life more difficult for the British after their easy defeat of the Italian Army in 1940.

From Benina, the SAS raiders were transported in 30cwt Chevrolet trucks, driven by the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), south-east to their desert base at Siwa Oasis, arriving on 21 June to learn of the fall of Tobruk. Instructing his men to withdraw to Kabrit, the SAS training base 90 miles east of Cairo on the edge of the Great Bitter Lake, Stirling headed to the Egyptian capital to see how he could be of help.

Amid the gloom and despondency at GHQ, Stirling was able to inform his superior that in the last six months the SAS had destroyed at least 143 Axis aircraft as well as laying waste to numerous petrol bowsers, repair bases and bomb dumps. It was even rumoured that the Germans had a name for Stirling, ‘The Phantom Major’, such was his ability to ghost on to airfields, wreak havoc and then vanish without a trace.

Stirling’s arrival in Cairo coincided with the decision of Gen Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief Middle East, to sack Neil Ritchie as commander of the Eighth Army and take on the role himself. Auchinleck was planning a counter-attack against Rommel to regain the coastal region around Mersa Matruh, and with this in mind he instructed Stirling, supported by patrols of the LRDG, to concentrate his unit at Qaret Tartura on the north-western edge of the Qattara Depression. From this remote base Stirling was ordered to attack airfields and enemy lines of communication in the Fuka–Bagush area, about 55 miles west of El Alamein, as the Eighth Army went on the counter-attack to drive Rommel west.

Siwa Oasis, where the SAS and LRDG operated from.

Stirling’s second-in-command, Capt Blair ‘Paddy’ Mayne, a huge man who had played international rugby for Ireland before the war, suggested to his commander that ‘it would be useful if a jeep could be provided to transport the elements of the Special Air Service Regiment to the scene of the operations’. Stirling liked the idea and managed to procure 15 American-built Willys Bantam jeeps.

Another SAS officer, Capt Lord Jellicoe, recalled that throughout this trying time Auchinleck was ‘sanguine’ despite the close proximity of the enemy, although ‘Stirling, as force commander, did not share this optimism’.

There was good reason for this, according to Jellicoe, as the SAS had never before been motorised. ‘Four days only were available for preparations’, he wrote in his operational report of the period. ‘15 jeeps had to be prepared with special equipment and guns and twenty 3 ton lorries loaded. This meant that the drivers and maintenance crews had to work, for some times, as long as 72 hours almost without a break.’

Consequently, there was a ‘great strain imposed on personnel of SAS Regiment and LRDG’ in the first week of July as they hurried to get ready for their new phase of guerrilla warfare. Ranged against them was Rommel’s Afrika Korps, its soldiers tired but bristling with the same self-confidence as their charismatic commander.