DAVID STIRLING – THE FAILED ARTIST

Born in 1915 in central Scotland, Stirling was one of six children of Gen Archibald Stirling, a veteran of the First World War, and the Honourable Margaret Fraser, fourth daughter of the 13th Baron Lovat. The Stirlings are an ancient, aristocratic family and David enjoyed a privileged upbringing even if it did entail boarding at the austere Ampleforth College. It was there, deep in the North Yorkshire countryside, that Stirling indulged his love of the outdoors as in his vivid imagination ‘he tracked wild beasts through the fields and hedgerows’. When he went up to Cambridge in the mid-1930s, Stirling was a gangly young man of 6ft 6in intent on enjoying life to its utmost. He lasted a year at Cambridge before deciding university wasn’t for him, so he settled in Paris with the aim of becoming a painter. But Stirling lacked artistic talent, and when told by his tutor to look for another outlet for his creative energies, ‘[I] was quite shattered as I had honestly believed it was only a matter of time before I smashed the barrier’. Depressed by his failure, Stirling set his sights on scaling Mount Everest, announcing his intention to climb the Himalayan peak. He trained first in the Swiss Alps and then in the Rocky Mountains in the United States. Moving south through Colorado, tackling the ranges in Park Gore and Sawatch, 23-year-old David Stirling interrupted his horse ride south to pay a visit to Las Vegas to win some money at the gaming tables. That done, he continued on towards the Rio Grande, arriving in early September 1939, where he heard the news that Britain and Germany were once more at war.

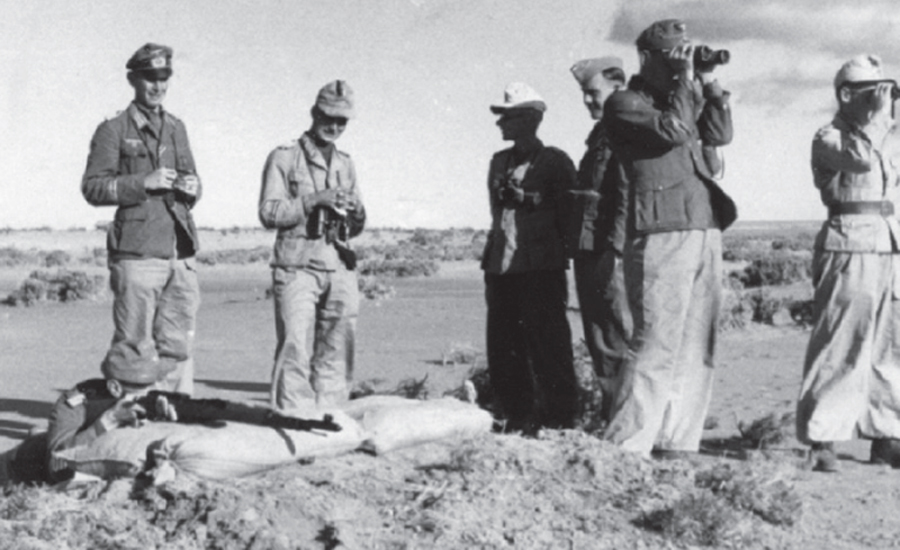

David Stirling faces the camera. The founder of the SAS rarely sported a moustache.

Stirling, a member of the Scots Guards Supplementary Reserve, returned to Britain and presented himself at the regimental depot in Pirbright. Stirling and the Guards were not a natural fit. The Bohemian side to his character did not sit well with the drill sergeants at Pirbright and on one occasion Stirling was reprimanded for his unclean rifle. ‘Stirling, it’s bloody filthy. There must be a bloody clown on the end of this rifle,’ exclaimed the sergeant. ‘Yes, sergeant,’ agreed Stirling, ‘but not at my end.’

Neither did Stirling endear himself to those senior officers whose job it was to lecture their young protégés on the art of war. Most of them, in Stirling’s view, held opinions that had altered little since the First World War, so the young officer spent increasing amounts of his time – and his money – drinking and gambling in London’s clubs. When he eventually left Pirbright he was described by his instructors as an ‘irresponsible and unremarkable soldier’.

Despite his lack of aptitude for regular soldiering, Stirling wasn’t short of belligerence and more than anything he wanted to fight the enemy. In January 1940 the 5th Battalion, the Scots Guards, were sent on a mountain warfare course in the French Alps and rumours abounded that they were going to be sent to help Finland fight the Russians. That mission never materialised and Stirling grew ever more frustrated with what had by now been dubbed ‘The Phoney War’. Then one day in the early summer of 1940 Stirling learned that volunteers were wanted for a special service force. He was accepted for the new force and posted to 8 Commando under the command of Robert Laycock. For the first time in his military career Stirling found himself among like-minded soldiers all desperate to have a crack at the Germans.