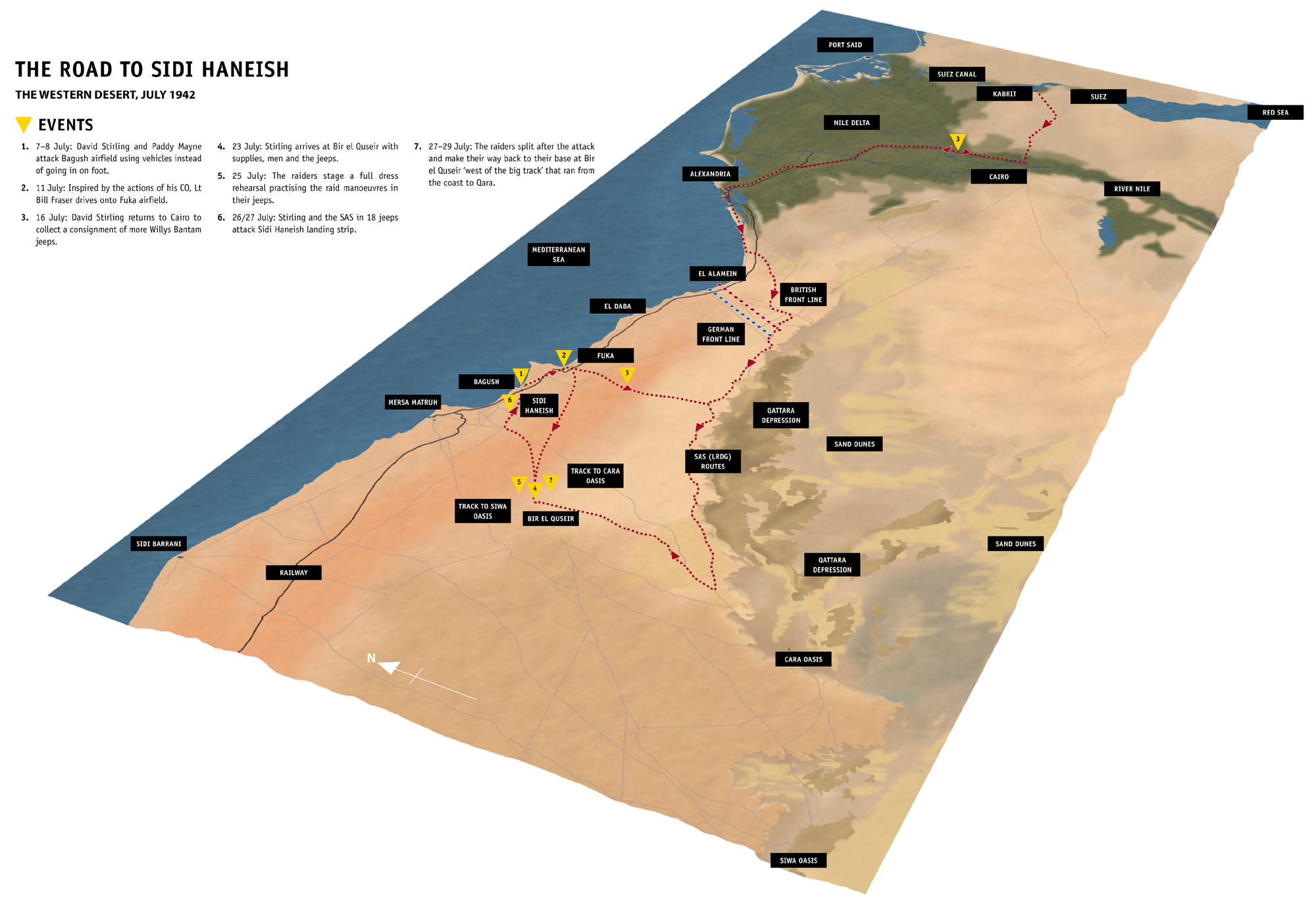

Back in Cairo Stirling presented himself at HQ Eighth Army whereupon he was issued with Operation Instruction No. 99. It stated:

Formation of a base at Qara Oasis.

You will discuss this with Lieut. Col Prendergast who will forward proposals to Eighth Army Tactical H.Q.

Priorities for Raiding.

The order of priorities is Tank Workshops, tanks, aircraft, water, petrol. You will use your own judgment in assessing the value and reliability of information, importance of target assessed in terms of numbers of tanks, aircraft, etc. and possibilities of successful attack.

Raids by other parties.

Eighth Army H.Q. will, whenever possible, keep you informed of other raiding parties operating in your area, but as these operations may have to be put on at short notice, no guarantee can be given that you will be warned in every case.

Blocking Operations.

In addition to the normal raiding tasks in para. 2 above, you will be prepared for the following operations:-

Operations at Sollum and Halfaya.

One detachment to initiate a traffic block at Sollum. This block will be maintained until a party of Royal Marines has been landed to exploit the situation and maintain the block for 48 hours. As soon as the R.M. party is in position you will hand over to them, and withdraw. You will provide a second detachment to block Halfaya and arrange to keep this block going for 48 hours if possible. The action of this detachment will be co-ordinated with the Sollum Detachment.

A party under Capt. Buck1 may collaborate with you if it is placed at your disposal by G.H.Q., M.E.

Blocking at Bagush and Gerewla.

You will prepare to initiate traffic blocks at Bagush and Gerewla. If these operations are approved instructions will be sent to you.

Intercomm.

You will arrange with Lieut. Col. Prendergast that all W/T messages sent by LRDG links reach you as soon as possible.

Members of B Squadron, SAS, plan a raid in late 1942. The officer in the middle is the noted desert explorer Wilfred Thesiger, who served briefly in the regiment.

Stirling must have read Instruction 99 with a mixture of excitement and anger. Section 2 would have put a smile on his face – the go-ahead to attack tanks and aircraft – but his heart must have sunk when he read that the SAS might be required to act as blocking troops to the Royal Marines (this idea was shelved by the GHQ’s Deputy Director of Military Intelligence because ‘handing over’ was deemed too impractical) or work with Capt Buck’s Special Interrogation Group.

Following recent events at Fuka and Bagush, Stirling was clearer than ever in his mind that a mass jeep attack would provide the SAS with a means of hitting the enemy again, both physically and mentally. As he told his biographer, Alan Hoe, nearly 50 years later: ‘It was not change for change’s sake … if we could keep them guessing and use a variety of tactics in such a manner that they never knew what was coming where, and how it was being delivered, we could sow real confusion in the rear.’

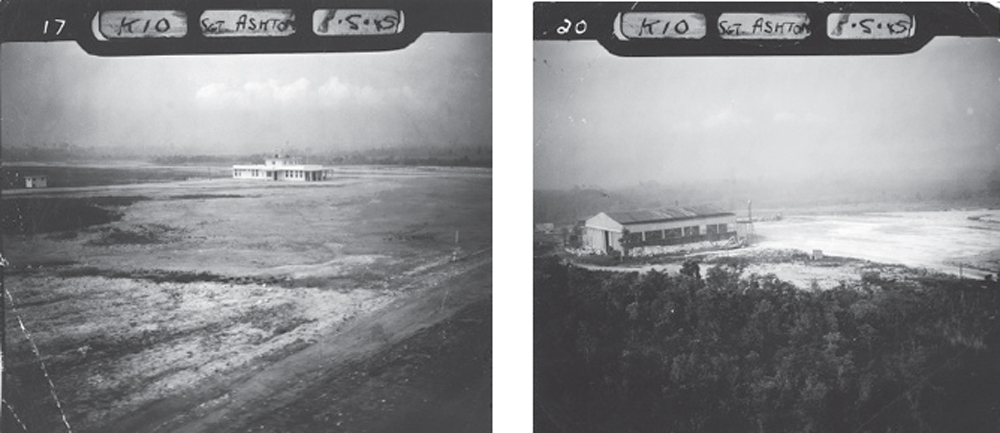

Reconnaissance photographs of an Axis desert airfield. They were used by the SAS to plan one of their many raids.

The problem was that Eighth Army HQ took a narrow view of the SAS. With Rommel just 65 miles from Alexandria it had plenty more pressing concerns in July 1942 than the feelings of Stirling. As Stirling told his biographer:

MEHQ still insisted on labelling us as saboteurs. Damn it, we were not saboteurs, we were a strategically effective force which could use sabotage as a tactic if the task called for it … the SAS was based on maximum achievement for minimum cost; who could possibly argue with that? I don’t believe that even Auchinleck, who had helped me so much, had wholly grasped the awesome potential of the SAS as a permanent unit.

Auchinleck, at least, still valued the SAS even if, as Stirling stated, his imagination failed to understand their full potential. But other staff officers in MEHQ disliked the SAS and their leader, believing that they were a renegade unit that should be absorbed by a more structured organisation such as the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

The antipathy was mutual. Stirling referred in private to junior staff officers as ‘fossilised shit’ and it was a constant battle with headquarters to get the supplies he wanted. It was Stirling’s belief that by pulling off a ‘spectacular’, such as a mass jeep raid on an enemy airfield, he would once and for all silence his enemies within MEHQ.

In order to lay the groundwork for such a raid, Stirling highlighted the advantages of using jeeps in a paper he submitted to Eighth Army Headquarters. In it he stated:

Attacks on landing ground have never before taken place when the moon was full; and the first attack at least would have the advantage of surprise.

The enemy’s tendency during periods of moonlight was to scatter aircraft over a number of landing grounds in order to minimise the effects of R.A.F bombing. They were too numerous to be adequately defended, and successful attacks would result either in a concentration of aircraft on a few well defended landing grounds, which would render them more vulnerable to bombing, or of tying up much needed troops by strengthening the defence of a large number of them.

A ‘mass attack’ would nullify the value of sentries on individual aircraft (the enemy’s normal custom) and would necessitate perimeter defence, which past experience has shown to be comparatively easy to penetrate by ‘stealth’. Thus the alternative employment of two methods of attack – either by a small party on foot reaching its objective without being observed, or by a ‘mass’ attack in vehicles – should leave the enemy hesitating between the two methods of defence. A combination of perimeter defence with sentries on individual aircraft would be the most uneconomical in men.

The psychological effect of successful attacks should increase the enemy’s nervousness about the defence of his extended lines of communication.

As Stirling careered around Cairo, gathering supplies and support, back in the desert the men he had left behind were enduring the full unforgiving force of the Libyan Desert.

On 13 July Capt Nick Wilder, the rugged and resourceful commander of the LRDG’s T Patrol – comprised of New Zealanders – wrote in the unit’s diary: ‘Major Stirling left for Cairo, leaving T Patrol and twenty paratroops behind. O.C. T Patrol put in charge (Wilder) of party. At 1800 hrs eight men from T patrol set off to watch main road and barrel route between Sidi Haneish and Fuka under corporal [Merlyn] Craw.’

Craw was a farmer from the north island of New Zealand, a tough man typical of his countrymen. For the next few days T Patrol carried out road watches on the route from Qara to Matruh, noting down all they saw of enemy transport.

The 20 soldiers of the SAS had received no orders from Stirling before he departed for Cairo other than sit and wait for his return. With their hideout at Bir el Quseir only 50 miles from the nearest Axis airfields, planes often passed overhead, so the soldiers were obliged to spend most of the day hidden ‘in the side of the long, fifty-foot high escarpment, like rabbits in a warren’. The jeeps and trucks had been concealed in the crevices of the escarpment and camouflaged with nets and scrubs.

‘We were under the continual apprehension that the enemy would discover our hideout by aircraft or by ground patrols,’ recalled Lt Carol Mather, who had joined the SAS from the Welsh Guards and Layforce. ‘There were so many tracks leading from all directions to our escarpment and running along the foot of the cliff itself that we had to take every precaution’ (Carol Mather papers, IWM). Mather and another officer, Lt Stephen Hastings, organised sentry duty atop a pimple on the escarpment. ‘From this point we could get a view of all the surrounding country,’ said Mather. ‘And we would search round and round with our glasses over the barren landscape, staring for minutes on end at dust clouds and vehicles which seemed to be making our way, only to disperse in mirages.’

Dick Holmes and Duggie Pomford joined the SAS in the late summer of 1942, later serving in the SBS.

Hastings had only recently joined L Detachment, having fought with the Scots Guards in the desert war, and he was still enjoying the contrast between his new unit and his former regiment. ‘We were a wild-looking lot,’ he recalled in his autobiography, The Drums of Memory. ‘Most wore a pair of shorts, sandals or boots with rubber soles and either bush hats or big khaki handkerchiefs over their heads like the Bedouin. We all had beards.’

Among the SAS soldiers were three French officers – Augustin Jordan, François Martin and André Zirnheld – who lived among their British comrades. The LRDG Kiwis kept themselves to themselves, burrowing into another part of the escarpment, while they rested between road watches.

The SAS envied the LRDG their tasks, wishing they had some way of breaking the monotony. Capt Malcolm Pleydell, L Detachment’s medical officer, wrote that ‘waiting is far worse than being employed on active operations’. Marooned in their desert hideout, fearful that they could be discovered by the enemy at any moment, Pleydell described their existence as ‘real anguish and bleak loneliness’. The boredom brought with it other problems – namely, water consumption. On operations soldiers often forgot their thirst in the excitement, but counting every second of every hour at Bir el Quseir they were as plagued by thirst as they were by flies.

Men sought solace in one another, palling up with their comrades to help pass the dragging, despondent hours. ‘In the early morning Steve and I would walk down … to our daytime cave near the cook-house,’ recalled Mather. ‘Here we would spend the remainder of the day. It was a long and low grotto with a floor of soft, white sand, at one end a great lip curved over, touching the ground and forming a cool enclosed space.’

Here the pair sheltered from the sun, reading one of the three paperbacks they had with them – The Virginians, Seven Pillars of Wisdom and For Whom the Bell Tolls – or engaged in conversation. One of their favourite topics was the marine fossils and shells embedded in the rock above their heads, the pair discussing how and when they got to be there.

Another soldier, Sgt Jim Almonds, one of L Detachment’s original members from 12 months earlier, one morning discovered more evidence of their hideout’s rich history. Spotting some pottery fragments among the escarpment he took them to Malcolm Pleydell. There were enough fragments to piece together a ‘beautifully symmetrical handle’ of a vase that Pleydell reckoned came from the Greek or Roman periods (Pleydell later presented the fragments to the curator of the Museum of Cairo who dated the vase to between 100 and 300 BC).

Pleydell also found plenty of marine fossils printed on the rocks of their hideout and at night, after their supper of bully beef mixed with biscuit and dried vegetables, he would lie on his back and study the stars overhead. The doctor wrote of the stars:

They were wise in their old age, wise, and probably very cynical as they watched the futile efforts of mankind. For, over two thousand years ago, they had seen the army of Cambyses march to its unknown fate.2 They had seen the Romans and Carthaginians locked in pitiless battle. They had looked down upon the Turks as they strove to hold the mastery of the desert. They had watched the childish brutality of the Italians as they tortured and drove the Senussi from one oasis to another. They had seen us warring in the desert twenty years ago, and now here we were back at it again. In a fraction of a second in the history of time, they had watched these little dramas of puny man – each, in turn, had strutted across the sandy stage and held it for a fleeting instant – and then the dust had blown over in its caressing forgetfulness, his traces had been concealed and his ways had become just a memory.

On 21 July, a week after Stirling and Mayne had left for Cairo, there was still no sign of them and the men at Bir el Quseir began to fret quietly. Lookouts posted on top of the escarpment scanned the horizon but each time a comrade called up from below if they could see something the same negative reply came back. On the afternoon of the ninth day both food and water were running low (they were now existing on a mug and a half of water a day per man), and Hastings, Mather and Pleydell started to discuss their options. Then, around 1600 hours on 23 July, they heard the sentry cry: ‘There’s vehicles in sight, sir, coming from the east!’

Grub’s up! An LRDG patrol waits for its supper at the end of the day.

Everyone scrambled to the escarpment and the officers held their field glasses to their faces and peered in the direction the sentry pointed. ‘Far away in the shimmering mirage which constituted our horizon we could see several little black dots,’ recalled Hastings. ‘Their shape kept changing; now some appeared elongated as if reflected in a bent mirror; two would merge into one and then part again. They were certainly moving.’

The question that neither Hastings nor anyone else perched on top of the escarpment knew was, were the vehicles friend or foe? The Bren gun was brought up from a cave and the soldiers cocked their weapons. ‘The minutes ticked by,’ said Hastings, ‘and then suddenly they emerged from the mirage, quite close and recognizable – jeeps and several 30cwt trucks. It was the column from Cairo.’

Capt Nick Wilder marked the event with a laconic entry in the LRDG diary: ‘23/7: Major Stirling returned from Cairo.’

Stirling was at the head of a 20-strong column of jeeps, ‘all of them bristling with Vickers K guns’, while the 30cwt trucks mentioned by Hastings were weighed down with supplies. A week earlier, at the request of Stirling, Capt Ken Lazarus of the LRDG had set out from Cairo with four trucks from the unit’s Heavy Section. Crossing the Qattara Depression, they deposited the supplies as arranged near the former hideout at Qaret Tartura. Stirling’s convoy had then collected them en route to the new base. The supplies included 1,500 gallons of petrol, 30 gallons M.220 oil, 30 gallons C.600 oil, 300 hand grenades, 5,000 incendiary bullets and an unspecified quantity of tea, sugar and powdered milk.

The LRDG Heavy Section, some of whom are seen here, were responsible for bringing supplies from Cairo to the SAS desert bases.

Welcome as the LRDG supplies were, the 20 or so bearded, burnt and famished men at Bir el Quseir were far more delighted to receive the supplies harvested by Stirling in Cairo. These included ‘tobacco, rum, new pipes, Turkish Delight and a pint jar of Eau de Cologne’. The return of Stirling was just the tonic the men needed. Hastings reminisced that ‘fresh fires flickered up that evening in the failing light … three brews of tea with rum and cigarettes afterwards.’

There were now about 50 men in total at the hideout and after supper Stirling gathered his officers around him. First they toasted his return with a wee drop of whisky, then Stirling got down to business. One item on the agenda was the introduction of some new faces, men who had come up from Cairo at the invitation of Stirling. Carol Mather remembered:

Sandy Scratchley, Chris Bailey and David Russell had come up with the new party, also another RAF officer to replace David Rawnsley. His name was Pike and he was an Australian who had just come off flying duties to help us in being supplied by the air. He was young, well-built and good looking. He had charm and great enthusiasm, and he was intrigued by everything about us – our beards, our jeeps and the way we lived and worked … Chris Bailey had transferred from the Cyprus company of the 4th Hussars and had spent over a year at Eighth Army HQ. Before the war he had kept an inn on Cyprus, which was renowned for its kitchen.

David Russell had recently arrived in Egypt with a Scots Guard draft. He was a wild and independent character, who enjoyed everything he did, who demanded complete obedience from soldiers, but who didn’t necessarily give it to his superiors – in this way he wasn’t popular with everybody.

Paddy Mayne, far right, and a group of SAS soldiers relax between raids.

Stirling also introduced the unit’s new navigator, Sgt Mike Sadler, formerly of the Rhodesian patrol of the LRDG, a man whose directional savvy had prompted Stirling to prise him from one special forces unit to drop into another. ‘I think Stirling got the jeeps first but hadn’t the means to navigate so that’s when he talent spotted me, if that’s the word, having seen me on early ops with the LRDG,’ recalls Sadler.

As the navigator for the Rhodesian patrol, Sadler had guided Paddy Mayne to Tamet airfield in December 1941 and subsequently worked with the SAS on other raids behind enemy lines. ‘Stirling had a very good social manner and also had a compelling personality,’ says Sadler. ‘He could talk you into anything, but he didn’t have to do much talking… He managed to make one feel you were the only person who could possibly do it, that kind of effect, but I also slightly felt he was thinking of something else at the same time.’

Even though Sadler had got Mayne to Tamet six months earlier, he knew less about the Irishman than he did Stirling. Nonetheless, he had seen enough of Mayne to know that ‘Paddy felt his true vocation in war; he was well suited to war and he enjoyed it … I don’t think he fancied the idea of being shot more than anyone else but he had a very good control of himself.’ As for comparing and contrasting the two men, Sadler said:

I always felt that the great difference between him and Paddy on an op was that Paddy was focused on the operation and knew everything that everybody was doing and where they were. David tended to be thinking ahead; next time we’ll need some other equipment and we could do it differently. I navigated him on a road we did up on a coast road somewhere, can’t remember where exactly, but we ran into a German laager that we shot up and pulled down some telegraph poles. There was a bit of fire from the Germans but once we got out of range of that he said ‘oh you drive now, Mike’ (at that stage I had been doing the machine gunning as well as the navigating) and he got into the other seat and curled up asleep. I was left with the task of finding the way back but he was rather like that. He was the strategic fellow, he had the ideas and was always thinking of improvements to make. (Author interview, 2003)

But the main topic of discussion that night was the mass jeep raid that had been fermenting in Stirling’s mind for the past ten days. Malcolm Pleydell recalled that Stirling explained first why the change in tactic was needed before outlining his plan. Using jeeps they would rely ‘on the sheer weight of firepower to overcome any defence that the enemy guards might muster’, their ‘machine-guns firing in tight concentration as the cars drove this way and that across the aerodrome’.

As for the target, Stirling unfurled his map and pointed to Sidi Haneish, a hitherto unmolested airfield approximately 30 miles east-south-east of Mersa Matruh and around 50 miles north of their hideout. Also known as Landing Grounds 12/13, it was regularly used by Axis aircraft and, in the words of Jim Almonds, ‘just begging’ to be hit.

Some of the SAS in the summer of 1942. The unit’s medical officer, Malcolm Pleydell, is standing second from the right in the middle.

Born in February 1920 in London, Mike Sadler grew up in the south-west of England and went to prep school in Cirencester. One of his teachers enthralled the young Sadler with ‘great stories about Africa and the tigers’ and shortly after his 17th birthday he emigrated to Rhodesia to become a farmer. On the outbreak of war, Sadler joined a Rhodesian artillery battery but differences of opinion with his commanding officer – and the tedium of his existence – made him look elsewhere for excitement. A chance encounter with some members of the Rhodesian patrol of the LRDG while on leave in Cairo led Sadler to join the unit in the autumn of 1941. After a little over six months’ service with the LRDG, Sadler was headhunted by Stirling and he remained with the SAS until the end of the war, rising to the rank of Captain. He received his commission from Stirling in unusual circumstances. ‘When we were in Cairo he said, “I want you to be an officer, go and buy some pips.” So I went down one of the bazaars and bought some.’ A few weeks later Sadler accompanied Stirling as he harried the retreating Germans into Tunisia. To add to the excitement, their unit was probably the first from the Eighth Army to link up with the First Army, which was advancing east after the landings in November in Morocco and Algeria as part of Operation Torch.

Unfortunately Stirling’s patrol was detected by the Germans and everyone except Sadler, Johnny Cooper and a French soldier called Freddie Taxis were captured. ‘For the next three days and four nights we walked from east to west with great salt lakes to one side,’ says Sadler of their escape. ‘Fortunately I knew the lay of the land and how to navigate but it was still pretty rugged going. We managed to replenish the goatskin [water bottle] with some brackish water from a well and we had a few dates for food to keep us going but that was it.’

Finally, they reached Free French lines at Tozeur in south-west Tunisia, where they were warmly welcomed. But that all changed when they were handed over to the Americans and driven the 200km to Tebessa under suspicion of being Fifth Columnists. ‘We were followed by a jeep load of guards in case we made a break for it, and also a jeep load of pressmen,’ recalled Sadler. ‘Then when they had checked up on us we were issued with US Lieutenant uniforms and we were OK after that … there was a bit of a fuss made about the fact we were the Eighth Army meeting the First Army. My local paper in Gloucestershire had an article headed ‘Sheepscombe Man in Desert Odyssey’. I think we were the first, unofficially, to get through and make the link.’

Mike Sadler, pictured here at the wheel of a jeep in France, August 1944, was a brilliant navigator who guided the SAS to Sidi Haneish.

The following day, 24 July, was one of theory. Stirling had the men assembled and explained in minute detail how the raid would unfold. Eighteen jeeps would participate in the attack, travelling to the target under cover of darkness on the 26th. As they approached Sidi Haneish from the south they would form a line abreast and ‘on a signal from him they would open up with a spectacular display of tracer bullets to silence the defences and give an impression of great strength’. With the enemy numbed by SAS firepower, Stirling explained that he would then fire two green Very lights, the signal for the jeeps to adopt a new formation; his jeep would be the tip of the attack with two more vehicles either side. Then on each flank would be a column of seven jeeps, spaced five yards apart, the guns of the left-hand column firing outwards and likewise the weapons of the right-hand column. The three vehicles that joined the ‘square’ would ‘move between the two rows of planes, with the guns of the three leading jeeps firing ahead at the defences’. Each jeep was armed with four Vickers K machine guns each with a rate of fire of nearly 1,200 rounds a minute; a twin Vickers on a steel upright in the front passenger seat and another twin Vickers at the right-hand side in the rear.

The 18th jeep, containing Mike Sadler, would not take part in the attack but instead would drive to the south-east corner of the airfield ready to pick up men in the event of jeeps being incapacitated for any reason.

Meanwhile, Capt Nick Wilder’s LRDG patrol, having set off with the SAS raiding party, would break off, and engage any defences west of Sidi Haneish while the attack was launched as a diversion. They would then ‘beat up any transport or enemy concentrations to the north west of the LG [Landing Ground].’

Stirling used a stick to draw the formation in the sand and then informed the men that the following night, 25 July, they would hold a full dress rehearsal to allow everyone to familiarize themselves with their role in the raid. After all, he said, ‘it was like learning a dance routine’.

Until then, concluded Stirling, they would drive half a mile or so from the escarpment and practise their formation until he was happy each driver knew what he had to do. ‘First attempts were muddled,’ admitted Stephen Hastings. ‘But eventually distances and drill were more or less perfected and the idea of the jeep charge became reality.’

Everyone found the dress rehearsal an almost surreal experience, driving around the desert, hundreds of miles inside enemy territory. ‘The rehearsal was one of the more bizarre moments of the war for me,’ recalled Johnny Cooper, ‘firing thousands of rounds deep behind enemy lines in preparation for a raid the following night.’

Pleydell would not be going on the raid, instead remaining at the hideout ready to treat the wounded on their return, but as a consolation Paddy Mayne allowed him to sit in his jeep during the practice. Squeezing between Mayne and the front gunner, with the rear gunner taking up most of the room behind, Pleydell had practically the best seat in the house for the dress rehearsal, which was conducted a few miles from their hideout.

‘David [Stirling] was in the centre of the front row, while we were out on the right flank of the square,’ recalled Pleydell. ‘At the given command we moved off across the scrub-scattered plain, little dark shadows lurching and bumping, with the drivers trying hard to maintain their correct position.’

The drivers discovered that keeping close formation at night was infinitely more challenging then during the day. Suddenly Stirling fired the first of his Very lights, said Pleydell, ‘throwing us all into a garishly green electrical sort of relief’. That was the signal for the gunners to join the fray. ‘Our magazines contained a mixture of incendiary, ball and armour piercing and tracer bullets,’ wrote Carol Mather. ‘We practised forming into line abreast and line astern, firing on the green Very signal from David’s jeep and following exactly in the tracks of the leaders. Every gun fired outwards and as I was driving and at the end of the left hand column, my front gun fired across my face and my rear gun behind my head so it was important to sit very still and not to lean backwards or forwards.’

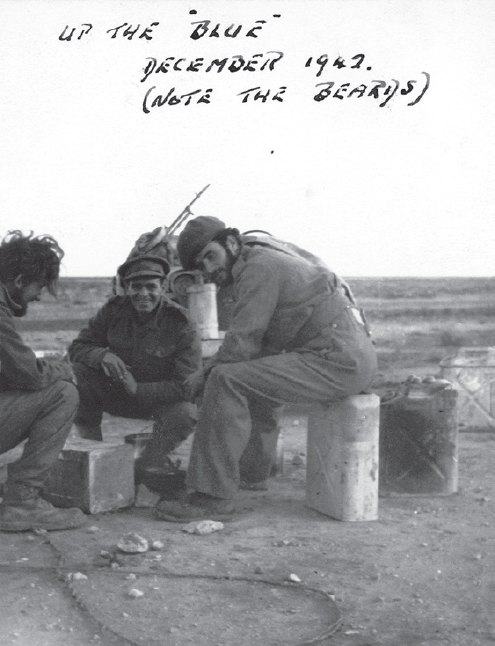

‘Up the Blue’ was the SAS slang for desert operations. Here three men take a break in December 1942.

Pleydell was almost overwhelmed by the violence of the four Vickers K machine guns in Mayne’s jeep, which shook ‘with each shuddering burst’. The noise was deafening and the men laughed at the sight of the pyrotechnics so deep behind the enemy lines. ‘We had a run-in of about 50 miles to Sidi Haneish and it was perfectly safe,’ reflected Sadler of the practice. ‘Really, the chances of anyone being within 20 or 30 miles of us was very remote.’

When Stirling was satisfied each jeep could change position and direction without a problem, he called an end to the rehearsal. On their return to the escarpment Pleydell was privy to Paddy Mayne’s understated style of leadership.

‘What direction are we driving in?’ he suddenly said, turning to the front gunner.

The man stared at the stars, trying to figure out which star was which. At length he replied:

‘North-east, I should say, sir.’

‘Ha!’ exclaimed Mayne. ‘You wouldn’t get far if you had to walk back.’

Changing gear, Mayne cast a sideways glance at his gunner and said quietly: ‘Mind you’re certain of your direction by tomorrow night.’

Pleydell fell asleep that night to the sound of George Jellicoe and Sandy Scratchley (a jockey before the war, described by a contemporary as ‘a famous hurdle race amateur jockey, the best of his time, a man of great common sense’) laughing as they reflected on the dress rehearsal.

The next morning the men were up early, wrapped up warm against the cold and relieved that for the time being at least they were not plagued by the flies that arrived with the midday sun.

Mather likened the activity on the morning of 26 July to:

the gold mining scene from the Seven Dwarves. There was much hammering and singing as new wheels and tyres were fitted, the Vickers guns were stripped and cleaned, magazines loaded, engines taken down and explosives made up. At one end two 4 gallon petrol cans containing bully stew were simmering over a large fire, at the other end David [Stirling] poring over maps and figures. Paddy [Mayne] fast asleep and unrecognisable entwined under a large mosquito net with his head under one jeep and his feet under another. George [Jellicoe] with a great tin of acid drops in front of him calmly working out the impossible problem of how much stuff we would want and how much we had got.

Men were pleased to be busy; it meant that thoughts of the raid were kept in the back of their minds. Nonetheless, recalled Johnny Cooper: ‘I think everyone felt a little bit of fear. But it was more eager anticipation – no one liked hanging around – and we had a desire to get on with it. We checked and rechecked our guns, the jeeps, and loaded the drums in the right order – one tracer, one armour-piercing and one incendiary.’

Mike Sadler, meanwhile, made sure of the route on the map. For him there would not be the stress of driving on to the airfield to shoot up the aircraft; rather he faced anxiety of a different kind. ‘There was a certain amount of pressure [as navigator] because there was always the worry you wouldn’t pull it off,’ he said. ‘There was somehow a lot of pressure on that one [Sidi Haneish] because it was a big party and it had a lot of key folk on it.’

Since he had arrived from Cairo a few days earlier, Sadler had got to know some of his new comrades better, besides Stirling and Mayne. Jellicoe he called ‘a great man’, Pleydell ‘a good doctor’ and David Russell ‘wild and self-confident … mad but a nice chap’. As for his fellow NCOs, Sadler took an instant shine to the inseparable pair of Johnny Cooper and Reg Seekings, both sergeants. ‘Reg and Johnny came from very different backgrounds,’ recalled Sadler. ‘Johnny was better educated and he was a “warrior”; he always wanted to be a soldier. You could sit down and have a chat with Reg but he was a slightly buttoned-up sort of chap.’

Some of the SAS Originals, including Reg Seekings (front) and Johnny Cooper (far right), both of whom took part in the Sidi Haneish raid.

Seekings, who thought Sadler looked like a ‘university professor’, was a hard man who had already won the Distinguished Conduct Medal in the desert campaign. The citation describes how ‘This NCO has taken part in 10 raids. He has himself destroyed over 15 aircraft and by virtue of his accuracy with a tommy-gun at night, and through a complete disregard for his personal safety, has killed at least 10 of the enemy.’

Born in the Cambridgeshire Fens in 1920, Seekings, along with Sgt Maj Pat Riley, were the only men in the regiment that Paddy Mayne knew to leave well alone, even when drunk. ‘I never had any trouble with him [Mayne] when drinking, nor [did] Pat Riley, because we weren’t worried about his size and we both had the confidence we could deal with him,’ reflected Seekings, a brilliant amateur boxer before the war. ‘And Paddy respected us for that so there was no problem.’

Sadler was right in his description of Seekings as ‘buttoned-up’. Like Mayne, Seekings was socially awkward, partly because of his rural upbringing and partly because of his accent. ‘The first time I went to London the Cockneys laughed at me because I talked slowly, like Fenmen,’ said Seekings. ‘But I said “Yeah, maybe, but we think a lot and if there’s something we don’t understand do you know what we do, and he said no and I said we hit it, and we hit it bloody hard, so watch it, mate”.’

Nonetheless, despite his gruff exterior, underneath Seekings was shrewd and perceptive, and surprisingly sympathetic to those less ruthless than himself. ‘Battle and fighting more or less face to face can be a bloody terrifying prospect for some people,’ he said. ‘I was good at it and I suppose to a certain extent I enjoyed it but it’s not everyone’s cup of tea. At one time yes I enjoyed the killing. I used to fret if a job was cancelled and I enjoyed the adrenaline rush. I was scared but I would have gone into action every day if I could.’

Johnny Cooper was the social opposite of Seekings, a man at ease in all company and a hit with the ladies who fell for his looks, wit and charm. The youngest soldier among the Originals, Cooper celebrated his 20th birthday in June 1942 and was known to Stirling as ‘Young Cooper’. Brought up in a middle-class family in Leicestershire, Cooper was an excellent sportsman and an enthusiastic actor (in a Wyggeston Grammar School play he had played Robin Hood to another boy’s Maid Marian – the ‘boy’ being a young Richard Attenborough), but he was also a skilled soldier, a former Scots Guardsman who had endured the debacle of Layforce.

He and Seekings may have had contrasting personalities but they hit it off from the moment they joined the SAS in the summer of 1941, even if Seekings did sometimes have to endure the more exuberant side of his friend during nights out in Cairo. ‘I did have a habit of singing once I’d had a few beers, I couldn’t help it,’ recalled Cooper. ‘Poor old Reg was very tolerant, although before we’d go out he’d often ask me not to start singing. But I think perhaps he secretly liked hearing me sing!’

1 Capt Herbert Buck MC, erstwhile of the Punjab Regiment, commanded the Special Interrogation Group, a unit consisting largely of German Jews who had fled Palestine.

2 Legend has it that Cambyses, son of Cyrus the Great, despatched 50,000 soldiers from Thebes to destroy the oracle at the Temple of Amun at Siwa in 525 BC. But during its march the Persian Army was swallowed up by a huge sandstorm. As no trace has ever been found of the army it is in all probability nothing more than a myth.