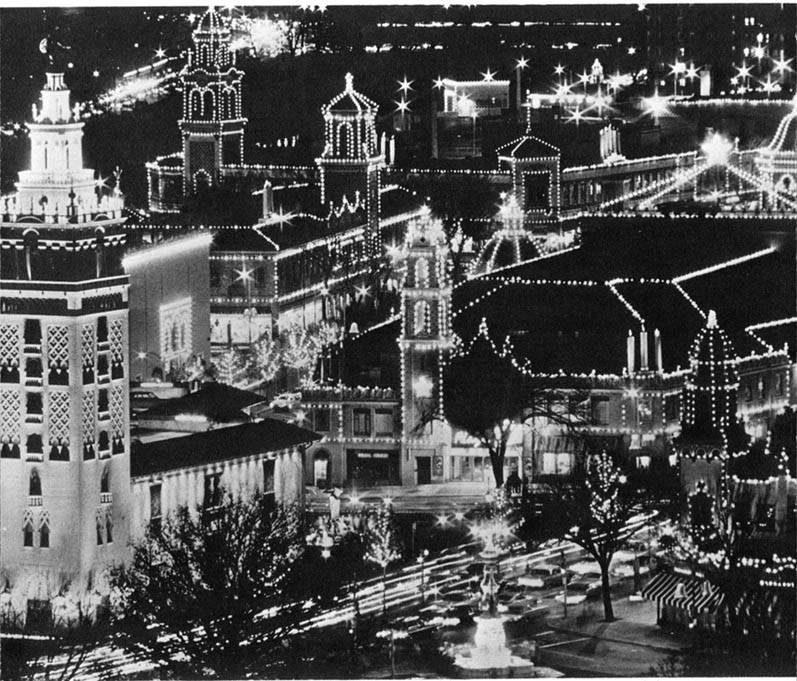

Courtesy of the Kansas City Chamber of Commerce

Christmas spectacular at Kansas City’s Country Club Plaza

Kansas City: Seville on the Missouri

There are at least two kinds of anonymous (or at least unpublicized) wealth—the kind that is perfectly happy with its anonymity, and the kind that isn’t, that would do anything to see itself better advertised. There is a lot of the latter variety in Kansas City.

First, Kansas City tells you, you must go to the bluff. Beyond the bluff, the land rises and falls in a series of hills and valleys which, by their ordinariness, give the bluff emphasis. Great importance is attached to this bluff. If, it is argued, the Missouri River had not encountered the bluff at this particular point in its course, the river would doubtless have continued southward, along a more or less straight path into the Gulf of Mexico. But the river met the bluff and was diverted by it and bent eastward. Its eastward thrust continues for some two hundred miles until the Missouri joins the Mississippi at St. Louis. This, if one continues to pursue this hypothesis, may have had a profound effect upon the course of American history. If the river had continued straight south and into the Gulf, if it had not been turned in a new direction by the sturdy bluff that leaps out of the plains, the North American continent might easily have remained a land divided into three parts by two great rivers, and under three flags—the British, the French, and the Spanish. This rationale might sound farfetched to some. But it does not to the citizens of Kansas City, which rises, straight and tall and proud, from the summit of this bluff. Parents take their children for Sunday picnics on the bluff where there is a sweeping view of unparalleled splendor. The river does seem to hesitate, irked to find this mighty obstacle thwarting it; then, resigned, it turns and presses on another way. The view from the bluff offers a kind of reassurance that Kansas City stands and has always stood—and firmly—at a point pivotal to the course of men’s affairs. As one man puts it, “We may not be fashionable, but goddamn it, we’re meaningful!”

The ideal, if impractical, way to approach Kansas City is on foot. A visitor who misses the experience of encountering the city in this fashion runs the risk of missing the point. To those willing to come as pedestrians across the apparently limitless miles of dusty plains that border the city on all sides, the city presents itself gradually, climbing out of the level horizon as a cluster of slender towers that cling together and pierce the sky like exclamation points, a strangely developing mirage of power and promise in the middle of the desert. The size and the strength and, at the same time, the elegance of Kansas City’s splendid skyline offer one of the city’s first surprises. To the arriving motorist, this is simply a more rapidly emerging phenomenon, and quite enough to pull the motorist’s eyes off the road. Newcomers have arrived here breathtaken. The view of Kansas City from across the plains has been compared, without tongue in cheek, to that of the spires of Chartres Cathedral as they lift from the flat farmlands of central France. And yet, how can Kansas City bear such a romantic comparison? After all, this is Kansas City, Missouri, symbol of the homely and the cornball, unfashionable in the extreme. Its founding fathers wanted to name it Possum Trot, and very nearly did. Kansas City is, isn’t it, the original cow town, home of the square, the lummox, the nasal-voiced booster and Babbitt, the graft-rich politician, the stockyard and the slaughterhouse? New York magazine once ran an advertisement asserting that readers would enjoy the publication “even if you live in Kansas City.” It was supposed to be a joke. Kansas City is a joke city, and all the Kansas City jokes are tired ones. No one, it is commonly assumed, would go to Kansas City unless he had to. And yet some surprisingly fresh breezes blow across the bluff.

“People are always so terribly surprised to find that Kansas City is a beautiful city, and that we have bright and attractive people here who have beautiful things,” says Mrs. Kenneth Spencer, a Kansas City grande dame, the widow of one of its leading industrialists (the Spencer Chemical Company, among other interests) and one of the leading supporters of local philanthropies, art, and culture. Mrs. Spencer is herself the possessor of quite a few of the beautiful things in Kansas City, including a vast duplex apartment filled with a museum-quality collection of eighteenth-century French and English antique furniture, Oriental rugs, Chinese porcelains, and a cabochon-cut emerald very nearly as big as the Ritz. “People from other places act as though they feel sorry for me, as though I had to live in Kansas City,” Mrs. Spencer says. “Obviously I don’t have to live in Kansas City. I live here because I simply love it!” Kansas City, so much maligned, evokes this kind of passionate love from among its citizens who defend their city—and defend it, and remind all who will listen, again and again, that Kansas City simply is not what it is so often made out to be. “Don’t you think my house is pretty?” asks Mrs. Spencer. “Don’t you think my view is pretty?” Her view is of a green and leafy park. “Why should I live in Paris when I have all this?”

The reasons why Kansas City is so often maligned and misunderstood are subtle and complicated, but one of them is simple: the rival city of St. Louis to the east. “The typical image of a Kansas City man is a guy chewing on a corncob pipe,” says one Kansas City man. “In St. Louis, they’re pictured riding to the hounds. Damn it, we ride to the hounds here too.” Another Kansas Citian asked at a Chamber of Commerce meeting not long ago, “How does St. Louis get away with calling itself ‘The Gateway to the West’? St. Louis is not the Gateway to the West. Kansas City is the Gateway to the West. We were always the most important junction in the western movement, and St. Louis never was. We were where the covered wagons provisioned for their journeys, and then we became a great rail center. Now, with TWA based here, we’re the great air center. St. Louis has just arbitrarily put up that Gateway Arch, just to have itself a tourist attraction. And it’s just as arbitrarily decided to call itself ‘The Gateway to the West.’ Gentlemen, we have got to do something to fight back.”

St. Louis and Kansas City see eye to eye on almost nothing. St. Louis, the older of the two cities (“but only slightly older,” one is immediately reminded when this touchy point comes up, since there is a mere thirty-year difference between the dates of the two cities’ charters) has, partly from being on the easterly side of the state, managed to convey a more East Coast impression of seemliness, cultivation, and tone. There is also a touch of Old South charm radiated by “old St. Louis,” and St. Louis society is frequently included among the perfumed upper circles of such social capitals as Philadelphia, Charleston, Savannah, and New Orleans. An edition of the Social Register is published for St. Louis. None is for Kansas City. There is even something distinctly different in the sound of the names of the two cities—St. Louis, soft and sibilant; Kansas City, rawboned, rough-and-tumble.

At the same time, Kansas City’s special character, and its special character problems, have much to do with several dynamic and strong-willed men who have successively left their personal stamps upon the city over the years. One of these was William Rockhill Nelson, the owner and publisher of the Kansas City Star. Mr. Nelson was something of a despot, with decidedly paternalistic notions, and, among other innovations, installed his Star employees in neat, old-English-style stone houses hard by his own mansion so that everyone on the paper could live “as one big happy family.” It worked, at least for a while, and though the houses have passed out of the Star’s control, they still stand and are highly regarded as residences. Nelson had grandiose ideas for Kansas City, and it was under his aegis that a German engineer and city planner named George Kessler was imported to create a master design for the city before it was too late. It was Kessler who saw a way to make brilliant use of the many natural valleys that ribboned the city; they would contain parks and broad tree-lined boulevards, and residential areas would be placed on the hills above, overlooking greenery. Thanks to Kessler’s planning genius, and the staunch backing of William Rockhill Nelson, Kansas Citians now enjoy more than fifty parks and over a hundred miles of inner-city boulevards and parkways. André Maurois once wrote, “Who in Europe, or in America for that matter, knows Kansas City is one of the loveliest cities on earth?” The man to thank for this is Mr. Nelson. When he died, he left a substantial trust for the establishment of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, which has become the city’s major art museum with a smallish but important permanent collection. Rather typically, Nelson left no funds for the maintenance of his gift, on the theory that if Kansas City citizens wanted a worthwhile museum they had better work for it. Today, fund-raising parties and benefits for the ever-needy Nelson Gallery have provided Kansas City social climbers with their most rewarding avenue.

Kansas City was supposed to expand to the northeast. Instead, it has done just the opposite, and the costliest and most fashionable districts are now on the southwest side of the city—many of them, including the high-priced Mission Hills area, across the state line in Johnson County, Kansas. This situation, with many of the choicest taxpayers living in another state, has created a knotty problem for the Missouri-based city government, and was the doing of another high-powered and individualistic man, Mr. J. C. Nichols. Nichols came to Kansas City in the early nineteen-hundreds and bought the first few of what were to become thousands of Nichols-owned areas, most of them on the southwest side of town. It was he who developed the Mission Hills and Country Club districts where, today, all the richest people live in big sprawling houses, along twisting roads and lanes laid out by Nichols interests. In his developments, Nichols was fond of using fountains, statues, huge stone planters and ornamental sculpture. And the profusion of these Mediterranean touches in Kansas City is another of this Middle Western city’s great surprises.

But Nichols’s masterwork was the creation of Country Club Plaza, and it did indeed represent a totally new concept in American architecture and commerce. It was nothing other than the first suburban shopping center in the world and, begun in 1920, it was foresightedly designed for the automobile age. Extensive parking space was planned for rooftops and within and beneath buildings. Today, the Country Club Plaza sprawls across forty southwestern acres and contains branches of all the best shops and restaurants, as well as professional offices. Because Mr. Nichols admired the Moorish style of southern Spain, he designed his shopping center with bell towers, minarets, courtyards, more fountains, more statuary, a scale replica of Seville’s Giralda Tower, and one fountain that is an exact copy of the Seville Light. In the years since, as a result of all this, Seville has been adopted as Kansas City’s “sister city,” a designation that technically doesn’t mean much other than to give city-proud Kansas Citians still another reason to crow, “Who needs Paris? Who needs Europe?” At Christmastime, the Country Club Plaza is decorated with thousands upon thousands of sparkling lights, and incoming planes on clear nights traditionally dip from side to side above the Plaza to let their passengers view the spectacle.

Not everyone in Kansas City admires the Country Club Plaza’s style of architecture, and many people point out, with some justification, that the Spanish style is not really appropriate to a river city in the American Middle West. Missouri is not, after all, California, and though the state did have a brief Spanish regime this left no lasting impression on the place or people. Particularly disparaging of the Plaza are those connected with the Kansas City Art Institute and School of Design, and those with the various museums. Craig Craven, a young member of the Nelson Gallery staff, describes the Country Club Plaza as “the capitol of kitsch.” When an outdoor art show was presented there, Craven denounced it as “open-air kitsch.” On the other hand, there is no question that the Country Club Plaza has become a successful real estate venture, and that it is continuing to become more so. Miller Nichols, J. C. Nichols’s son who now heads the giant company, has announced that the Plaza will before long contain a three-hundred-and-fifty-room hotel. Without question, it will be built in a style that would look right at home in Andalusia.

During the nineteen-twenties and -thirties, one of the most enthusiastic supporters of Mr. Nichols’s building projects, and of the lavish use of concrete in highways (to say nothing of in fountains, statues, and ornamental urns) was Kansas City’s notorious political boss, Thomas J. (“Big Tom”) Pendergast, and his Pendergast Cement Company. Until the Pendergast machine’s inglorious end in 1938—when more than two hundred and fifty people were indicted on charges of voting frauds, and the corruption of the Pendergast regime lay dismally exposed with the Big Boss himself sentenced to prison for tax evasion—developers like Nichols received Pendergast’s full co-operation, which was of important help. But, of course, “Nobody” in Kansas City talks about that now.

Also of significant help to the builders and developers of Kansas City have been various members of the Kemper banking family. The Pendergasts were hardly among Kansas City’s “right people,” but the Kempers very definitely are, and they have been for some time. When you think banking in Kansas City, you think Kemper. The first Kemper, William T., arrived here in 1893, with his wife, the former Charlotte Crosby, a lady of inherited means who was also a shrewd businesswoman. Charlotte Kemper made cautious loans of money from a tin strongbox which she kept under her bed. It was she and her husband who loaned J. C. Nichols the money to buy his first ten acres of land. The Kempers may have been a bit rough about the edges in the old days, but they have since acquired all the patina needed for entrance into the loftiest social circles, and they are said to consider themselves the grandest people in Kansas City.

To say that the Kempers have Kansas City banking pretty well sewn up would be putting it mildly. The Kempers own both the first and third largest banks in town: the City National Bank & Trust Company and the Commerce Trust Company. The second largest bank is thereby totally eclipsed by Kempers. Kempers also own or control some twenty-one smaller banks in Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, and Oklahoma. They also own a great many blocks of downtown Kansas City real estate and, through their other investments, the Kemper name decorates the lists of boards of directors of very nearly every important industry in town, plus such national firms as Owens-Corning Fiberglas and the Missouri Pacific Railroad. The Kempers of Kansas City are all very rich, but the family should not be regarded as a monolithic money structure. The Commerce Trust and the City National Bank are in fierce competition with each other, and the two brothers who for many years headed them—the late James M. Kemper of the former bank, and R. Crosby Kemper of the latter—were on such poor terms with each other that they rarely spoke. There have been other intrafamily ruckuses among the Kempers. When the young Crosby Kemper, Jrs., embarked on the building of a large and costly modern home, of a design so extreme in its use of glass and brick pylons that conservative Kansas Citians were horrified, many of the couple’s relatives were critical and told them so. The storm grew to such proportions that the Kempers were angrily divorced before the house was finished. When the house was done, however, the pair patched things up and remarried each other.

“Boss” Pendergast was in favor of concrete streets and fountains, but of not much else that could be considered interesting or important, or even lasting. During the long two decades of his reign much of Kansas City life—particularly its cultural life—slid into a slough of apathy and inactivity. World War II came soon after Pendergast’s collapse, and so it has only been in the past twenty-odd years that Kansas City has been trying to pull itself back up to a level where it will have as much to offer culturally as other cities of half a million population or over. This has not been an easy task, because Kansas City businessmen, in whom strong traces of the free-for-all spirit of the Old Frontier still seem to linger, have always been frankly more interested in making money than in giving it away—particularly to something called “culture” which some men equate with downright sissy. The culture drive has received the endorsement of the faculty of the Art Institute and those connected with the museums—the so-called “artistic community”—but since some of these people have longish hair it is easy for a more conventional part of the community to dismiss them all as hippies or limp-wrists.

Several of the younger generation of Kansas City’s older families have, however, been earnestly backing the cause of Art. As a result, the arts here have been becoming increasingly respectable and have even made their way into the society columns. Young Mrs. Irvine O. Hockaday, Jr., works as a volunteer at the Nelson Gallery, young Mrs. Patrick Graham toils on behalf of the opera, and young Mrs. Albert Lea is into anything that will benefit the Kansas City Philharmonic and so on. There are a number of wealthy young collectors who have set about with determination to prove that, as far as art is concerned, everything is very much up to date in Kansas City. One couple has a collection including works by Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Roy Lichtenstein. Mrs. Thomas McGreevy and her broker husband have focused their attention on op, or psychedelic art, and all the pieces in their otherwise traditional Kansas City house either glow, blink, flash, or emit unearthly sounds. Mrs. McGreevy, a former actress, has gone so far as to appear in an underground Kansas City film—and in the nude. Actually, she insists, it was a flesh-colored body stocking, but when her banker father-in-law saw the movie he was so shocked by what went on in it that he had the footage suppressed.

Another group of younger people has established the Performing Arts Foundation, dedicated to bringing better theater to Kansas City. The group includes the ubiquitous Mrs. McGreevy, Mrs. Crosby Kemper, Jr., and David Stickelber, a witty bachelor who lives in an elegant apartment with upholstered walls and Oriental rugs everywhere, even in the kitchen because “it keeps the help happy.” The Stickelber family fortune comes from the manufacturing of a bread-slicing machine—“It’s the only kind there is, you can’t slice bread without it,” as the scion of the company says. Eyebrows went up in Kansas City when Maria Callas came to stay with David Stickelber “to forget” during the period when she was being replaced in the affections of Aristotle Onassis by Mrs. Jacqueline Kennedy. “Maria insisted on my creating the illusion that time was passing rapidly,” Mr. Stickelber explains. “So each day I would go into her bedroom and say, ‘This is December. Tomorrow it will be January. Thursday will be Valentine’s Day’—and so on.”

The bright young crowd in Kansas City speak often—and often bitterly—of their parents’ generation which they feel, with some justification, is not doing what it might to support the arts in Kansas City. It is the older generation, of course, that still manages to hold most of the purse strings. The young group is particularly resentful of such people as the senior R. Crosby Kempers, who, it is felt, with their great wealth could have done much more for the city than they have and who, with the generally conservative banking policies they represent, have actually exerted a negative influence on the city’s cultural life.

Still, for a number of years Mrs. Kemper senior headed the Jewel Ball, a debutante affair that benefits both the Nelson Art Gallery and the Kansas City Philharmonic. In fact, Mrs. Kemper founded the Jewel Ball—or so she says. The senior Mrs. Hockaday also says that she founded the Jewel Ball, and neither woman will give the other credit. What appears to have happened is that Mrs. Hockaday had the idea of having a ball, and Mrs. Kemper added the debutantes. In any case, it is still Kansas City’s most important debutante affair—indeed, the only one that counts.

“The Kempers are worth millions and millions of dollars,” says Molly McGreevy, “and so is Miller Nichols. Wouldn’t you think people like that could spare just a few hundred thousand for the Performing Arts Foundation?” So far, the answer appears to be no.

Then there are rich Kansas Citians like Mr. Joyce C. Hall, the man who created Hallmark and guided it to where it is, one of the wealthiest corporations in the world. No one knows how rich Mr. Hall is because he is a reticent type and Hallmark is still a family-owned company, with its earnings a closely guarded family secret, but his holdings are said to be vast indeed. The Halls, who aren’t particularly social, have contributed only minimal amounts to the city’s cultural institutions, and the Kansas City Museum of History and Science was happy to receive, last year, a check for twenty-five hundred dollars from Mr. Hall. Meanwhile, the Nelson Gallery does somewhat better, and recently reported Mr. Hall’s gift of fifty thousand dollars. Though the greeting card business might seem to align itself with art, the Halls at the moment are much more interested in a development called Crown Center (the Crown being from Hallmark’s trademark), an eighty-five-acre urban renewal effort in downtown Kansas City encompassing nearly all the land between the old Union Station and the Hallmark headquarters, an area of real estate roughly two-thirds the size of Chicago’s Loop. Crown Center has been designed to contain shops, apartments and office buildings, a new hotel, underground garages, and acres of parks and greenbelts. When completed, an estimated two hundred million dollars of Hallmark money will have been spent.

The older generation of Kansas City’s rich continues, with a few exceptions, to do what it has always done. There are the hospitals to support. There is the Westport Garden Club to enjoy—probably the city’s hardest-to-join club since no more than fifty women may belong at any one time. There is the River Club, a downtown eating club high on the bluff overlooking the river—also considered exclusive—which the men enjoy for lunch and couples enjoy for dinner. There is the Kansas City Country Club. There are, in other words, the traditional pleasures and pastimes of moneyed Middle Americans who have “settled in” to middle-sized cities. These families regard such eccentricities as the young McGreevys’ blinking and beeping collection of art as harmless phases which the young will one day certainly outgrow.

And, in the meantime, Kansas City—as those in the young crowd are so painfully aware—lags a long way behind its rival city to the east when it comes to culture. Compared to what St. Louis can offer, Kansas City’s History and Science Museum is, at best, a third-rate institution, though its energetic young director, Robert I. Johnson, is determined to do something about this situation. The Nelson Gallery has one of the three—the others are in Boston and Washington—finest collections of Oriental art in the country. But in other categories its collection is definitely a skimpy one. The most famous alumnus of the Kansas City Art Institute was the late Walt Disney. “Culturally, Kansas City has got to be given a shot in the arm,” David Stickelber says. And the money to do it with is so maddeningly, frustratingly there. Mrs. Crosby Kemper, Jr., who ought to know, says, “This is a tough town in which to get people—the people who really have it—to put two nickels back to back.”

Some Kansas Citians explain their situation by pointing out that Kansas City has never had a major rich-family benefactor—the way, for instance, Pittsburgh had Mellons, Wilmington had du Ponts, Detroit had Fords, and New York had Rockefellers. On the other hand, many people see it as a city with any number of potential big benefactors, each one too shy—if not too stingy—to make the first big step.

There is still another explanation. Years ago, St. Louis recognized the cultural wellsprings that could be tapped—and the purse strings that could be loosened—by turning to its large and well-heeled Jewish population. For many years, St. Louis has been inviting prominent Jews onto the boards of its museums and opera and philharmonic orchestra, and has made healthy use of the traditional Jewish interest in the arts and learning. Kansas City, perhaps for reasons of snobbery or ignorance going back to the rawboned frontier days, failed to tap this rich source. As a result, Kansas City’s Jews withdrew into their own tight circle, with their own clubs and philanthropies and institutions. Recently, however, Kansas City became aware of what it was missing and losing, and a definite effort is now being made to draw Jews into the general community. The names of wealthy Jewish families—the Morton Soslands, the Paul Uhlmanns, the Aaron Levitts—now decorate the important boards and committees. Now Jewish girls are being taken into the Junior League and are presented at the Jewel Ball. A few of the old barriers remain, of course. There are no Jewish members of the Kansas City Country Club. Jews have their own, the Oakwood Country Club.

There is another breed of rich man in Kansas City who may be having a lot to do with shaping the city’s future—the new-made millionaire. An example of this sort is Ewing M. Kauffman, whose Marion Laboratories, Inc., grew from where, some twenty years ago, Mr. Kauffman was mixing pills and cures and lixiviums in his own basement by the light of a sixty-watt bulb. Today it is a company worth about two hundred million dollars, and Mr. Kauffman himself says he is worth another hundred million. The Kauffman magic formula, according to the man who invented it, is profit-sharing. He operates a generous plan by which his employees are made to feel a part of the company they work for, and a part of its success. Kauffman boasts that at least twenty of his top men now have profit-sharing accounts in the millions. “My receptionist downstairs is worth half a million,” he says. “I just retired a maintenance man who had a quarter of a million. Look at these people—happy, happy, happy!” And, as Mr. Kauffman gesticulates in their direction, his employees smile, and smile, and smile. Part two of the Kauffman formula is that you must work as hard for Kauffman as Kauffman works for Kauffman (often fifteen or sixteen hours a day), or out you go—with your profit-sharing account no more than a memory.

Ewing Marion Kauffman, who says, “I wanted to be Kauffman of Marion Laboratories, not Kauffman of Kauffman Laboratories, there’s an important difference” (though business rivals hint darkly that he simply invented “Marion” as his middle name) is a man so totally lacking in modesty that his huge self-esteem more or less passes for charm. When he entertains, he urges his guests to make after-dinner speeches extolling Ewing Kauffman. After each tribute, he applauds approvingly. He lives in a huge brick fortress on a hill that prominently displays itself to the street below, and from his house he flies two big flags from two big flag poles, the American because he is proud to be an American, and the Canadian, because he is proud of his blondely beautiful and Canadian-born wife. His house is full of delights, including an Olympic-size swimming pool, a sauna and a steam bath, a pipe organ, a ballroom, and a fountain electronically geared to splash to the accompaniment of music and colored lights. “I’m just learning to use my wealth,” he admits. “Now we give two hundred and fifty thousand dollars to charity every year.” One of his most recent big outlays, however, was to purchase the Kansas City Royals, a baseball team, because “my wife wanted them.”

There are, as they say in Kansas City, not many people around like Ewing Kauffman. At the same time, there are too few people in Kansas City like Mrs. Kenneth Spencer, whose husband died several years ago. In 1966, Mrs. Spencer wrote out a check for $2,125,000 to build a graduate research laboratory at the University of Kansas, her husband’s alma mater. She continues to make sizable gifts to a long list of philanthropies. The Spencers had no children, and so one day Kansas City will doubtless benefit importantly from Mrs. Spencer’s fortune.

Not long ago a group of young Kansas City businessmen sat at lunch at the Kansas City Club, the downtown eating club for men. The group included Jerry Jurden, vice president of ISC Industries, a securities outfit; George Kroh, a real estate developer, Bob Johnson of the History and Science Museum, Gordon Lenci, headmaster of the Barstow School, one of several private day schools in the city, and Irvine Hockaday, Jr., a young lawyer. No one at the table was over forty, and most were not more than thirty-five. And, as it almost inevitably does, the subject came up of what was wrong with Kansas City’s “image.”

“Kansas City had a lot of things going for it around the turn of the century,” one man said. “The Armours were here with their meat business, Fred Harvey’s headquarters were here, all the major truck lines came through here, and of course there was the river port. But look what’s happened to Dallas, compared with what’s happened to us! Compared with us, why should a city like Dallas even exist? Yet Dallas is known as the Big D, and everybody laughs at Kansas City.”

“We’ve got to overcome apathy,” George Kroh said. “We’ve still got a lot here. We’ve got cattle, oil, industry, a broad economic base—clean air, and no ghettoes. Of course there’s not much glamour in being Mr. Clean. We’ve got the Mission Hunt, the Polo Club—and still we’re thought of as a bunch of hicks in a nowhere cow town.”

“One thing Kansas City is not—it’s not provincial,” Bob Johnson said. “I found that out when I moved here from Chicago. This is a very aware city. The people here know what’s going on in the world.”

“That,” another man pointed out humorously, “is because of our location. We’ve got no ocean, no lakes, no mountains to go to—we’ve got to get out of Kansas City to find all that.”

As for culture, the young men agreed that Kansas City has always been more oriented toward sports. “Still, you see a lot of people going to the theater now that you used to see at the ball games”—and there was general agreement that Big Tom Pendergast’s influence on the city’s cultural life had been disastrous. “And now,” George Kroh said, “there’s so damn much infighting going on among the various art groups. The Lyric Opera is fighting the Philharmonic, and the Performing Arts Foundation is fighting the Kempers, and all the different museum groups are fighting each other. We need some sort of unifying force.” At the same time, it was pointed out, an exhibition of art owned by Kansas City collectors, held at the Nelson Gallery, had drawn some three hundred works from a hundred and ten different collections, with tastes ranging from Gainsborough to de Kooning and Warhol. And, someone else added, “I’d say that at least ninety per cent of those collectors were people under forty.”

Irvine Hockaday, who is active in city politics, nodded emphatically and said, “Yes, this is a beautiful city, a great place to live. The only thing wrong with Kansas City is what Mayor Davis said. Did you hear what Mayor Davis said? He said, ‘All this town needs is a few more funerals.’”

Senator Wherry, in a broadside against the Red Chinese, once said, “We will lift Shanghai up, up, up to Kansas City if it takes us a century!” So much for Senator Wherry, and so much for Shanghai. As for Kansas City, funerals are, alas, inevitable, and we shall see how high Kansas City climbs.