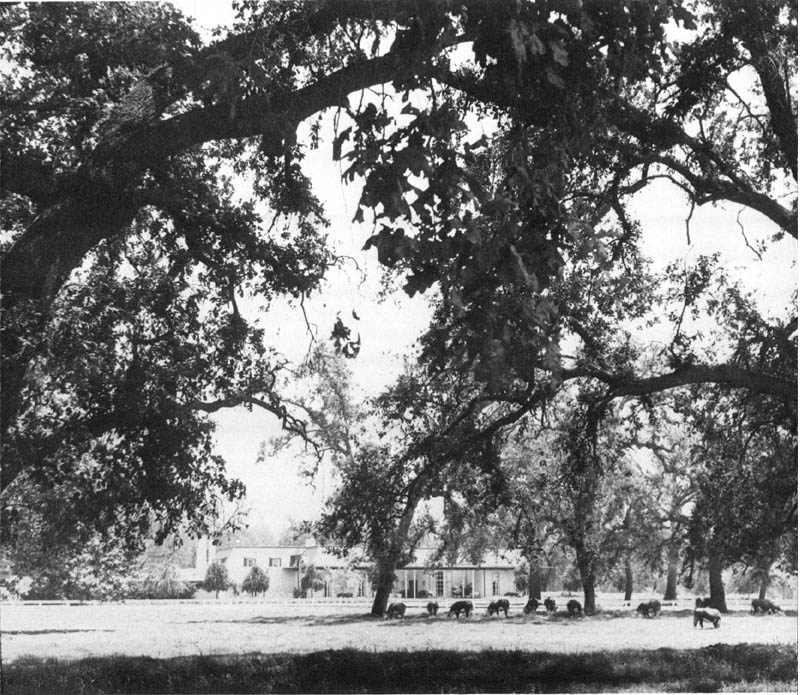

Courtesy of the Fresno County and City Chamber of Commerce

Luxury and livestock in California’s Central Valley

California’s Central Valley: “Water, Wealth, Contentment, Health”

Colusa, California, is not provincial either. Nor are Bakersfield, Fresno, Modesto, Stockton, Lodi, Sacramento, Chico, or Redding, to name a few other Central Valley places. And yet, like Kansas City, they are disparaged and made the butt of all the jokes. The lyric of a recent hit song runs, “Oh, Lord, stuck in Lodi again!” Not long ago, Herb Caen, the San Francisco columnist and chronicler, led off a column with “Lodi’s leading playboy (and that’s funny right there) …” And in a review of Fat City, a novel by Leonard Gardner, a news magazine wrote, “The place is Stockton, California, a city filled with a litter of lost people, most of whom pile on urine-smelling buses each morning and head for the onion, peach, or walnut fields for a killing day on skinny wages.” In fiction, Colusa has fared no better.

Broadway producers say that if a reference to Canarsie gets a laugh in a New York show, the California road company can get an identical laugh by substituting “Modesto,” or “Visalia,” or “Yuba City.” In fact, any Valley town will do.

The Central Valley of California contains some of the lushest agricultural land in the world, and the Valley’s towns and cities are the homes of some of California’s—and the country’s—wealthiest families, who lead lives of quite splendid luxury. A “litter of lost people”? That would hardly apply to the Weber family of Stockton, founders of the city, who own vast ranches of peaches and tomatoes, or to Mrs. Tillie Lewis of the same city, another tomato tycoon, who made an enormous fortune when her canneries developed a way to take sugar out of canned fruits and juices, or to Mr. Peter Cook of Rio Vista, said to be “so rich that he doesn’t lease out his gas wells—he drills them himself.” Then there are people like the Alex Browns, so rich that they found it more practical to open their own bank than to bother with ordinary commercial accounts, and the McClatchys, owners of the Valley’s largest newspaper and radio-TV chain for four generations.

In Modesto, there are the Gallos, largest wine producers in the world, and further south there are hugely wealthy families such as the Giffens of Fresno. Russell Giffen, from an office furnished with eighteenth-century antiques, directs a ranching operation with acreage in the hundreds of thousands (so many hundreds of thousands that he is not quite sure just how much land he owns), raising cotton, barley, wheat, safflower, alfalfa seed, melons, tomatoes, and a good deal else. Urine-smelling buses indeed! Central California garages practically overflow with air-conditioned Cadillacs and Rolls-Royces. The men who drive the big harvesters for Martin Wilmarth—who harvests, along with other produce, twelve hundred acres of rice in Colusa—sit in comfort in air-conditioned cabs. Another Valley farmer has a fleet of custom-made Cadillac pickup trucks, also air-conditioned, said to be the only vehicles of their sort in the world. At the same time, California’s Central Valley, though it is the largest single region in the state, where over two hundred products are grown—products which become ten per cent of what America eats—the area has remained the one part of the state which hardly anyone outside it knows; which few outsiders see or visit, and which fewer understand.

Even Mrs. Ronald Reagan speaks without enthusiasm of her current address in Sacramento, the state capital and the Valley’s largest city. “Thank heavens we can escape to Beverly Hills on the weekends!” Nancy Reagan says, adding that she has to go to Beverly Hills at least once a week to get her hair done. “No one in Sacramento can do hair,” she sweepingly asserts. Like most people from Los Angeles and San Francisco, Nancy Reagan had never spent much time in the Valley and had never set foot in Sacramento until her husband was elected governor. When she did, she was horrified by what she found and has been complaining bitterly ever since, to anyone who will listen, about the house where she was expected to live.

The California governor’s mansion, a turreted affair of Victorian gingerbread built in 1878 and painted a glittering wedding-cake white, was immediately unacceptable. “There are seven fireplaces, none of which can be lit,” Mrs. Reagan has said. “The house is on a corner facing two gas stations and a motel, and it backs up on the American Legion Hall where I swear there are vile orgies every night. The house was condemned fifteen years ago. I said to Ronnie, I can’t let my children live there!” Upon seeing it, Mrs. Reagan immediately refused to occupy the mansion, and the Governor indulged “Mommy”—as he calls her—and rented a house in the suburbs of the city. Since then, Nancy Reagan says that she has been “too busy” to get to know any of her Valley neighbors. She made one trip to the Sacramento branch of I. Magnin & Company, California’s favorite fashion store, and found its contents inferior to those in the stores in Beverly Hills and San Francisco, where she still prefers to shop. “Here, everything is scaled down for these Valley farm women,” she says.

These, needless to say, would be nothing short of fighting words to the women of the Central Valley who, among other things, are among Mrs. Reagan’s husband’s staunchest supporters. A great many Valley families are older-established than families in San Francisco and Los Angeles, and these consider themselves among the oldest of California’s Old Guard. The first families of the Valley were here long before gold was discovered in the tailrace of Sutter’s Mill, near Sacramento, and these families descend from men and women who crossed the Sierras on foot, before the days of the covered-wagon trains. And yet, as they are most acutely aware, young women from the Central Valley are not invited to join the debutante parties in San Francisco and Los Angeles, and Valley men languish far longer on the waiting lists of San Francisco’s select clubs such as the Bohemian and the Pacific Union. “It’s because of our cow-town image,” they say with resignation, and they suffer from an inferiority complex even more severe than their counterparts in Kansas City.

Geographically, San Francisco and Los Angeles people have always treated the Valley as something to be endured, a place to be got through. You have to get through Bakersfield and Visalia in order to get from Los Angeles to Yosemite Park. From San Francisco, it was necessary to get through Sacramento in order to get to Lake Tahoe or Squaw Valley—until the new freeway managed to speed the motorist over the rooftops of Sacramento without its really being visible. The old Route 99 that used to take you up and down the length of the Valley had, to be sure, a perverse way of leading the motorist through the most woebegone sections of each Valley town it encountered, and there was, as a result, no encouragement to turn off the main highway and explore. After a trip through or across the big Valley it was easy to leave it with the impression that it was little more than a flat—very flat—expanse of fields and orchards, punctuated by glum skid rows and trailer camps. Now, in a sense, the freeway system has made it worse. You can traverse the Valley without even knowing it’s there.

And yet it is. Over the round, dry, coastal mountains that shelter San Francisco, through such a pass as the Altamont, and then down into the Valley, you know, when you encounter it, that you are in a somehow special place. There is a special smell, which changes with the seasons, from the smell of loamy earth to the perfume of blossoms and unfolding leaves to the drying of eucalyptus bark at the end of summer. Each harvest has its smell—sweet and winy grapes, dusty tomatoes. There is also a special hazy paleness to Valley sunlight and, in winter, special ghostly fogs and mists that rise from marshes and canals and river beds. There is also a special language here. Ask for directions, for example, and you might be told: “Head up about a mile past Harris’s piece till you pass a prune orchard on your right and some apricots on your left. Then take your next right, which will put you up onto the levee, then go along the slough till you hit a grove of wild wormwood trees.…”

The Central Valley of California is actually a pair of valleys placed end to end, created by two rivers—the Sacramento, which flows south out of the Sierras, and the San Joaquin, which flows north. The two rivers merge in a fan-shaped delta east of San Francisco, and then empty to form San Francisco Bay. Like Kansas City’s famous bluff, the much-advertised beauty of San Francisco Bay would not exist if it had not been created by the convergence of the Valley rivers which, of course, spill out at the end of their journey through the Golden Gate. The topography of the double valley, which is, on a relief map, as though a great scoop had been drawn down through the center of the state, is responsible for the Valley’s special climate. Moist air from the Pacific is turned back by the coastal range of mountains and, on the eastern side, the towering Sierras collect westward-moving weather in the form of rain or snow. Thus the Valley remains hot and dry throughout most of the year, and it “never” rains from April to October. At least it’s not supposed to rain during these months.

From the earliest days of California settlement, men struggled with the problems, and the promises, which this particular climate offered. During the long summers the rivers shrank to a trickle or dried up altogether, and the Valley became a desert. In spring, when the snows in the mountains melted, the rivers overflowed and the Valley became an inland swamp. You can tell which are the oldest of the Valley houses because they are built on high foundations, well above the ground, and are approached by long flights of steps, a reminder of the threat of high water that existed only a few years ago. Obviously, what the Central Valley needed was a way to store the spring floods and to distribute this water during the dry summer growing season, and from the first sandbagged levees along the Sacramento River and the digging of the first canals, ditches, and sloughs, this battle with water has been the Central Valley’s major effort. In fact, the story of the Valley, and its economic success, has been written in water.

One of the first to recognize the Valley’s potential in a large way was a man called Henry Miller (no kin to the novelist of the same name who also lives in California). Henry Miller remains, in some ways, a figure of mystery. His real name was Heinrich Alfred Kreiser. He was the son of a German (or perhaps Austrian) butcher. He came to the United States in 1847 at the age of nineteen, and when he heard of Sutter’s gold he decided to head for California. When he went to pick up his steamer ticket to Panama he noticed that, for some reason, his ticket had been made out in the name of Henry Miller. This, at least, is what he claimed. Did he come upon the ticket dishonestly? In any case, the ticket was stamped “Non-Transferable,” and so the young man, who spoke little English, decided that it was wisest to pretend to be Henry Miller rather than risk losing the ticket. He kept the name until he died.

In California, he worked for a while as a dishwasher and then as a sausage peddler, and it was as a sausage man that he first entered the Central Valley and was struck with its possibilities. He was a quiet, reclusive young man, and as far as is known had no formal engineering training. Yet he began, in his spare time, to design levees and intricate irrigation systems. He also began to buy land which was considered worthless and which he could therefore buy dirt-cheap. Henry Miller—who, in his later years, developed grandiose ideas about his capacities and took to comparing himself with King Solomon—may have been a genius. He was certainly a clever salesman, and perhaps he was a scoundrel. In the days of feverish railroad-building and the speculation in land that was central to the allure of railroads, Miller was able to persuade various fledgling railroad companies to lay their tracks along certain routes. Then, when tracks were ready to be laid, Miller would discover a “better” route. The first route would then be abandoned, and its roadbed would become—by default—a ready-made levee for Miller’s expanding irrigation system. Once, buying a parcel of land from a Spanish owner, Miller agreed to accept “as much land as a boat can circle in a day” in return for the price he offered. He then strapped a canoe to his wagon, set off at a fast clip across the countryside, and, by nightfall, had claimed a considerably larger portion than if his journey had been by water.

At the height of his career, Henry Miller and his partner, Charles Lux, another ex-butcher, owned over half a million acres of Valley land, on which a million head of cattle grazed. Miller and Lux were America’s first cattle kings, and it was once claimed that whatever California real estate Henry Miller didn’t own the Southern Pacific Railroad did. Miller liked to boast that he could ride from Mexico to the Oregon Border, on horseback, and never be required to sleep on land that was not his own. He was also responsible for the law of riparian rights, which provided that anyone owning land along a river can use the river’s water. This gave Miller complete control of all the water in the San Joaquin Valley, a considerable resource. Today, Henry Miller’s heirs and others who have inherited shares of the Miller-Lux holdings, are immensely rich. Henry Miller died in 1916, and the beneficiaries, direct and indirect, of his enterprises include such far-flung people as Mrs. William Wallace Mein, Jr., of San Francisco, who is Henry Miller’s great-granddaughter, and Mr. Wilmarth S. Lewis of Farmington, Connecticut, the celebrated Walpole scholar, biographer, and collector of Walpoleiana.

Henry Miller pointed the way toward what could be done with water in terms of Central Valley agriculture. Since then, water has been at the heart of every Valley triumph, and every controversy. Feelings about water can be joyful; several years ago, when a new canal was opened carrying water from the Shasta Dam in the north into previously unirrigated southern areas, a bright indigo dye was thrown into the water at the source and, as the blued water made its way into each Valley settlement along the course of the new canal, the populace turned out and there were civic celebrations, speeches, parades, cheering, and all-night dancing in the streets.

Feelings about water can also run hard, stirring bitterness and resentment. In the southernmost part of the Central Valley, many people are angry about a plan to lift water out of the Delta and carry it, through a mountain tunnel, into Los Angeles, where it is badly needed because of that city’s rapid growth. What right does Los Angeles have to “our” water? the northerners ask. A bit of graffiti in a Valley men’s room reads, “Please flush after using. Los Angeles needs this water.”

In the years since the pioneering Henry Miller, water has been chained behind a series of high dams and directed through hundreds of miles of canals and pumping stations, tunnels, reservoirs, and power systems. The Operations Control Center of this operation, in Sacramento, resembles the interior of a futuristic space ship, complete with wall-sized maps, flashing lights, computerized controls, all coordinating the release and flow of water throughout the Central Valley Project. The Control Center not only regulates the amounts of water that flow out, and where these gallonages go, but also the kinds of water—for drinking, for irrigation, or for industrial use—that are needed in any given part of the state of California at any given time. From here, the levels of rivers are controlled to keep barges afloat, to keep salt water from encroaching on peach orchards, to keep water temperatures at the proper levels to promote the spawning and the growth of fish. The Center is an operation of mind-boggling proportions, and it is getting bigger all the time. New dams are being built “that make Aswan look like just another PG&E project,” according to one Valley engineer. The Folsom Dam, west of Sacramento, already dwarfs the Aswan. The drawing boards teem with others.

With all these dams, and all the water they store, there has been a certain nervousness about what might happen in the case of a serious earthquake, and when, several years ago, there was an extended earthquake scare, a number of people hurried to higher ground, because if all the dams in California did break open at once, the entire Valley would certainly become a very damp place in which to live. In the meantime, the irrigation that the big dams provide has turned the Valley floor, in the spring, into a sea of billowing pink, white, blue, and orange blooms. And when they contemplate the wealth of agriculture that the Central Valley water system provides, Valley people are understandably resentful of city folk in San Francisco and Los Angeles who poke fun at Valley farmers. “Where would they be if it weren’t for us?” one woman asks. That the Governor’s wife feels she must go to Beverly Hills to get her hair done strikes Valley people as less an insult than a joke.

One way to grasp the special feeling of the California Central Valley is to begin in the south, in Bakersfield, a city which once belonged almost entirely to Henry Miller. Bakersfield is to the Valley what the bluff is to Kansas City, but the comparison cannot be stretched too far. Bakersfield is cotton, and Bakersfield is oil. Cotton has given Bakersfield a sense of permanence; cotton money, that is, is older money, rooted in the soil. Oil money gives Bakersfield a sense of transience, of come-and-go, because oil money is new money, based on a black substance that is always puddling up from beneath the substrata of the earth, and oil brings with it drillers and refiners and promoters and speculators, all of whom seem to have flown into Bakersfield from somewhere else. Today, virtually every oil company of any size has an office in Bakersfield, and it is hard to spend more than an hour in Bakersfield without a sense of the throbbing of pumps, refineries, and compressor plants that make gasoline out of natural gas, and of course a concurrent sense of oil-smelling money.

Money is a favorite topic of conversation in Bakersfield—who made how much, and when, and why, and who, because of failure to be in the right place at the right time, failed to make money. The Tevises and the Millers, for example, represent a long-standing money feud. Like Henry Miller, the Tevis family were also big landowners in these parts (though on a somewhat lesser scale) and, in the 1930s, the Tevises found themselves land-poor. Miller, at that point, had succeeded in diversifying his interests. In order to recoup their fortunes, the Tevis family interests formed something called the Kern County Land Company, and shares were sold to the public—thereby departing from Tevis family control. Lo and behold, not long afterward, a bonanza in oil was discovered beneath Kern County Land Company acreage. Kern County Land Company shareholders found themselves rich overnight, and at least one man—Mr. C. Ray Robinson, the lawyer who had handled the Land Company’s affairs—made himself a million dollars in legal fees alone, not counting what the jump in value of his stock netted him. Tevises moaned and gnashed their teeth but, alas, there was really nothing they could do; a fortune had slipped through their fingers. At one point, the Tevis mansion in Bakersfield had a private golf course, and the Tevises had actually entertained foreign royalty in their home. The big house had to be sold, and for a while it was used as the clubhouse for the Stockdale Country Club. Today, the site belongs to a San Franciscan named George Nickel, a Henry Miller heir—and a cousin of Mrs. William Wallace Mein—and none of the Miller-Lux heirs today feels the slightest guilt about gloating over the fact that Millers still outweigh the Tevises.

Moving north up the wide Valley, the next important town is Fresno. To many people, Fresno is more typically a Valley town than Bakersfield because it is solidly agricultural—vigorous, masculine, where cowboys wear their hats in the fanciest bars, yet a town with an elegant downtown shopping mall, reclaimed from a former slum, that has become a model for city planners everywhere, and a number of sleek new high-rise buildings. Fresno is at the geographic center of the state, and Fresno County is the richest agricultural county in the United States—as very few Fresnoisans will forget to remind you. The irrigated land around Fresno produces a great variety of crops, and it is here that the psychology of the California farmer is seen at its best. He is tough, pessimistic, politically conservative, fiercely independent. If there is one thing a Valley rancher resents it is “folks from outside trying to tell us what to do.” The folks from outside are usually from the federal government, and at the heart of the continuous grumbling about the Central Valley irrigation project, and what kind of water will go where from which dam, is the fact that it is a U.S. Department of the Interior project—representing damned outsiders from Washington.

Stewart Udall—though long departed from his post as Secretary of the Interior—is still a dirty name in these parts, and a kind word for ex-Labor Secretary Willard Wirtz not long ago landed a man in a Valley rancher’s heated pool—where he was discovered floating face down. Wirtz did away with the bracero program, which ranchers—now that it is no more—speak of in retrospect as though it once provided something like a second Eden. The braceros were Mexicans brought into California during peak-picking seasons to perform “stoop labor,” the gathering of low-growing fruits and vegetables. “Why, the braceros were the greatest boost to the Mexican economy there ever was!” one rancher insisted not long ago. “The Mexicans who came up here loved the work, and they were wonderful workers. A good picker could make anywhere from sixty-five hundred dollars to ten thousand dollars a season! They came out here and said we should put heaters in the bunkhouses—heaters! A Mexican’s not used to a heater! They said, ‘Why aren’t you feeding them meat? Why aren’t you feeding them eggs?’ My Lord, don’t those damn fools in Washington know that a Mexican eats tortillas and beans?”

Valley ranchers admit that they may have used the wrong public relations tactic when Secretary Wirtz came out to California several years ago to look over the conditions in which the Mexican laborers worked and lived. The ranchers, hoping to woo Mr. Wirtz to their point of view, put on a big party for him, and that turned out to be a mistake. Wirtz was a teetotaler, or at least he rather frostily refused the many stiff drinks urged upon him, and Valley ranchers pride themselves on their capacity for alcohol. Wirtz also made a point of not eating a bite of the elaborate barbecue that was spread before him. He went back to Washington and canceled the bracero program.

Another Valley rancher said not long ago: “The national farm program has been conducted as a relief program for the South. Farm legislation on a national scale has been controlled by the South and the Midwest. California keeps getting the short end of the stick. The chairmen of both the House and the Senate agricultural committees are Southerners. Meanwhile, we’re caught here in a cost-price squeeze. Our taxes go higher, labor costs go up, but our customers have concentrated their buying power. There used to be, for example, hundreds of canneries for the cling-peach people to go to. Now there are nineteen or twenty. Those of us who sell direct to markets—well, there used to be thousands of little ones to shop from. Now there are just a few big super-chains. So it’s harder for the farmer to fight for his price.”

Adding to their woes, the farmers have lost control of the California Assembly and state Senate. The large landholders used to have great power in both, but under the one-man-one-vote system, their voice is much less effective. Now, though the Valley ranchers remain resolutely Republican, the Valley counties usually go Democratic.

And, needless to say, Valley ranchers had few kind words to say for Mr. Cesar Chavez and his striking table-grape pickers, whose headquarters were in Delano, some seventy-five miles south of Fresno. “We weren’t about to have some labor organizer tell us what to do,” one rancher says. “Why, California pays the number one farm wage in the country, and the grape pickers are paid the best! Why couldn’t he pick on states that were behind?” Mrs. William Harkey, the wife of a wealthy peach rancher in the little town of Gridley, says, “Of course I bought grapes all through that whole darned thing. I didn’t buy them to eat, of course, because they’re terribly fattening, but I fed them to my pet raccoon.” Of Senator Edward M. Kennedy’s support of the table-grape boycott, the slightly sick Valley joke quickly became, “Confucius say, ‘Man who boycott grapes should not play in Martha’s Vineyard.’”

Valley ranchers are endlessly gloomy about their labor problems, and some insist that there can be no solutions. “The only people making money here are the developers,” one rancher claims. “They’re buying land at three thousand dollars an acre and selling it for housing at three thousand dollars a lot. Twenty-five years from now, this whole Valley will be nothing but houses, and all our fruits and vegetables will be coming from Africa.” Still, despite the cities’ sprawl, California’s harvested acreage continues to increase. Another rancher says, “When they took away the braceros, they forced us to use the winos. Those decent hard-working Mexicans have been replaced by the dregs of society.” It is true, during the harvest seasons, that trucks gathering up winos from the slums and backwaters of Valley towns for work in the fields make the image of “urine-smelling buses” an apt one. At the same time, the labor shortage has forced the farmers to increase the mechanization of their farms. More and more, computers are feeding cattle and machines are shaking peaches out of trees, replacing human hands. This has meant that, though the California farmer may not have been able to raise his prices by much, and though his machines are expensive, they have enabled him to increase his yields enormously. California farmland grows increasingly valuable. The average California farm, of 617 acres, is today worth $325,000. The national average is 389 acres—worth only $69,000. It seems likely that California farmers will continue to be able to afford their air-conditioned cars, their heated pools, their private planes, and their wives’ seasonal forays into I. Magnin’s, for some time to come.

One of the most difficult things, perhaps, for a Valley farmer to understand is why the average laborer is unwilling to work as hard as he, the farmer, does. During the harvest season, the farmer rolls up his sleeves and goes into the fields where he will work for fifteen or twenty hours a day, seven days a week. His wife, meanwhile, will put her Magnin’s dresses aside and put on dungarees to work as a weighing master, while the rancher’s sons and daughters are stooping and picking in the hot sun, side by side the winos. Why—the ranchers ask—aren’t farm laborers happy to do the same?

The economic rule of the Valley is: the cheaper the water, the higher the value of the land. In the northern part of the Valley, where water is much more plentiful and thus cheaper, a farmer can operate quite profitably on a smaller acreage. The northern Valley is blessed with a larger river, the Sacramento, with more rainfall, and with the precious boon of a vast underground lake, called Lake Lassen, which makes irrigation possible through the use of wells. This means that the northern part of the Valley, from Sacramento north, is also the prettiest part. There are more and bigger trees, and there is a leafy shade in the northern towns that is not possible in the hotter, dryer south. Modesto—with its welcoming archway proclaiming, as one enters the town, “WATER, WEALTH, CONTENTMENT, HEALTH—MODESTO”—is a town of peach orchards and vineyards. Stockton and Sacramento concentrate on tomatoes. Further north, in Colusa and Chico, there is an emphasis on almonds and walnuts, whose larger and deeper root systems require a larger water supply.

When water first came to these towns, in some cases as recently as a generation ago, schoolchildren turned out in their Sunday best to plant seedlings of trees along the streets and highways, and today these have become tall stands of eucalyptus, sycamore, live oak, and pistachio trees (these turn a brilliant red in autumn). Sacramento is a particularly leafy city, with trees along both sides of most of the older streets, trees whose branches meet to form a solid canopy overhead, and a large central park, where the state capitol stands and where thousands of camellias burst into violent bloom in early spring.

Chico is another green place, and many of its streets are appropriately named after trees. At the heart of Chico is an extraordinary twenty-four-hundred-acre natural park where the original wilderness of the early Valley is carefully preserved. The park was donated by General John Bidwell, who founded the city. “He was mixed up with Sutter and all the rest,” one local resident explains, “and his wife was big on Christianizing the Indians.” Bidwell Park was the setting of the original Robin Hood film, with Errol Flynn, because its thickly clustered live oaks, festooned with grapevines, were considered the closest thing to Sherwood Forest. Hidden in Bidwell Park are two natural lakes and what Chico used to boast was “the World’s Largest Oak.” In 1963, the World’s Largest Oak was split by a lightning bolt, and so now the Chamber of Commerce of Chico advertises that it has “Half of the World’s Largest Oak.” Chico’s tree-lined Esplanade, with its handsome houses, provides one of the prettiest city entrances in America.

The northern Valley is full of surprises. “Down River” from Sacramento lies the rich and beautiful Delta region. Roads here wind narrowly along the tops of levees, across bridges, over sloughs and waterways that cross and split around islands in an endlessly complicated pattern. Boats have been known to lose themselves for days in these waters. Big, prosperous-looking farms, with handsome Victorian farmhouses, lie below the levees. (The roadways here are frequently at the level of a house’s second-story windows, for many of these houses stand on land that has been reclaimed from the riverbed and is actually lower than the water table.) Each farm has its dock and pier where crops can be loaded into river barges. One gets the feeling that these farms have been operating in much the same fashion for at least a century, which turns out to be just the case. One suddenly crosses a bridge and a sign proclaims, “Locke—pop. 1002, elev. 13 ft.” Locke is a Chinatown, a community of Chinese that was first established here when the railroads were being built and that has chosen to remain here. Above its Chinese lettering, one of Locke’s shops proclaims itself to be a “Bakery and Lunch Parlor.” Another sign exhorts, “DRINK! LIQUORS!” Down below the levee is an eating establishment of unprepossessing appearance but of great local celebrity called Al the Wop’s. Al the Wop’s is famous for its steak sandwiches and French fries.

North of Sacramento is the pretty river town of Colusa. Not long ago, Colusa celebrated the one hundredth anniversary of its incorporation, and visitors at this event were taken on tours of California’s second oldest court house (1861), and the Will S. Green mansion (1868). Will S. Green founded Colusa and is venerated as this part of the Valley’s “Father of Irrigation,” since it was he who first surveyed the Grand Central Canal in 1860. Colusa also has a mini-mountain range all its own, the Sutter Buttes, which spring up surprisingly from the otherwise flat Valley floor to jagged peaks of over two thousand feet. With typical Valley pride and fondness for superlatives, the Sutter Buttes are promoted as “the World’s Smallest Mountain Range.”

It used to be that the Central Valley floor had a panoramic view of the snow-capped Sierras to the east and the lower coastal range of mountains to the west. Wherever you went in the Valley, the old-timers say, the mountains hung on two horizons. Today, they rarely show themselves, and this is the price the Valley has had to pay for irrigation. The air is no longer as dry as it was, and a misty haze nearly always obscures the mountains. Irrigation has also subtly changed Valley weather. It used, literally, never to rain in summer, but in recent years there have been sudden flash summer storms. These can be disastrous to certain crops. Peaches, for example, if hit by rain must be harvested within exactly seventy-two hours. Otherwise, brown spots appear, the peaches will not pass inspection, and an entire year’s crop —and income—will be lost. This happened to the peach ranchers of Modesto in 1969. Now, in addition to labor and Washington, the farmers bemoan the uncertainty of the weather—which, ironically, their own irrigation brought them.

Continuing north, one begins to encounter around the town of Corning, low, rolling hills. Then, through Red Bluff and Redding—lumber towns—one enters the high hills and pines, and the Valley is over. The Sacramento River, wide and sleepy as it spreads across the Delta, is a racing torrent here, a mountain stream. Climbing still higher, along a winding road with an Alpine feel to its bends, one comes to the Shasta Dam, from which the Sacramento River now issues through giant penstocks. At Shasta Dam, the visitor is barraged with statistics—how many thousands of kilowatts the dam generates (enough to light half the world), how many miles of recreational lake-shore the dam created, how many billions of gallons the man-made lake can store (enough to cover the entire state of California to the depth of one inch). On the horizon stands the white and symmetrical silhouette of Mount Shasta, whose seasonally melting snows help fill up the enormous lake.

Meanwhile, back in the state capital, young C. K. McClatchy is the fourth generation of his family to operate the “Bee” chain of Valley newspapers. There are Bees in Sacramento, Fresno, and Modesto, and Mr. McClatchy’s wealthy maiden aunt, Miss Eleanor McClatchy, heads up McClatchy Enterprises, which includes radio and television stations. (A fifth generation of McClatchys is waiting eagerly in the wings.) C. K. McClatchy, typical of Valley men, has a special feeling about the place and what it means. “There is a sense, here,” McClatchy says, “of the continuation of history—of the Gold Rush, of the opening up of the West, of the growth of California from the earliest pioneer days to where it is now the most populous state in the union. And you get a sense here of how history has moved—swept, been carried, into the present, and how the present has maintained the integrity of the past. The Valley has kept up with its history like no other place I know of. Just go and stand on the rim of Shasta Dam”—called “the Keystone of the Central Valley Project”—“and see the thing that is the source of so much that has happened to the Valley and beyond it, and you’ll see what I mean, why I find this Valley, plain and flat and conservative as it is, one of the most thrilling places to be alive in that I know.”

And so this is one of the right places, too. Who needs Paris here, either?