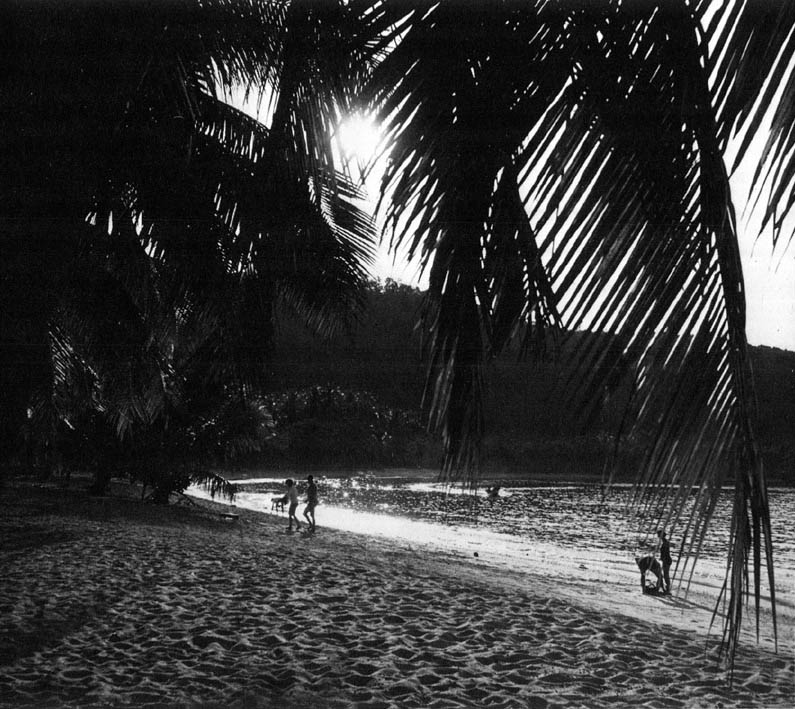

Photo by Dick Davis, Photo Researchers, Inc.

The beach at Zihuatenejo

Mexico: In Search of What Acapulco Used to Be

Travelers have become as restless and changeful of their ways as resorts and small suburban towns—endlessly searching out new and just right places. The new breed of new rich, thirsting to find itself in the new social scheme of things, keeps looking for new oases of pleasure and peace.

And so, when American travelers say that a resort is ruined, they mean that it has been improved. Conveniences—such as the mixed blessing of air conditioning—have been installed. When Americans say that a resort is ruined, they mean that its prices have risen to equal those of other resorts. On both these counts, Acapulco certainly qualifies for the ruined, or at least considerably damaged, label, and so for several years the search has been on for the perfect little beach resort that is “just like what Acapulco used to be”—cheap, inconvenient, somewhat squalid, but with miles of white sand and turquoise ocean, where palm leaves click in sunny breezes, and where fat fish leap onto the line.

Excited reports have come back from this or that little-jewel port—reports which announce that this is it; this is what Acapulco was. All these reports have had the heavy support of local chambers of commerce, needless to say. And, needless to say, they have been contradictory, confusing.

The west coast of Mexico is favored (or afflicted, depending on your point of view) with a particular topography along nearly its entire length: stern and abrupt ranges of the Sierra Madre Occidental rise steeply from the ocean’s edge, leaving the towns and villages of the coast cut off from the interior. Such roads as exist frequently turn into surging rivers in the rainy season, and a number of places are accessible only from the sea or by air. (This was once true of Acapulco, before a superhighway made it an easy drive from Mexico City.) The same terrain is repeated along the skinny peninsula of Baja California. Indeed, the mountains of Baja are so brave, rock-strewn, and arid—spiky with cactus, wild with jaguar, deer and bright parrots—that most of the peninsula is still an unpopulated wilderness. There are stretches where Baja California is scarcely more than thirty miles across, and yet those thirty miles from ocean to gulf are next to impossible to travel by land. Las Cruces, a hamlet in Baja, is in one of these remote regions. Though only forty miles from La Paz, Baja’s capital city, Las Cruces does not appear on most maps of Mexico and, making use of a bumpy landing strip, can only be reached by privately chartered plane.

Las Cruces got its name, according to the local legend, when Cortes first sailed into the Gulf of California in 1535 and put ashore in the tiny harbor—before sailing north to discover the larger, more protected harbor at La Paz. Upon landing, there was a skirmish with the Indians, and three of Cortes’s men were killed. Years later, three stone crosses—one larger than the others, possibly to indicate that one was an officer and the others enlisted men—were found lying on their sides in the undergrowth. These crosses, one is told, were carried to the top of a hill overlooking the harbor and erected there, though they hardly look to be over four hundred years old.

In the late 1940s, a dashing young Mexican named Abelardo Rodríguez—whose wife, the former Lucille Bremer, once danced in a film opposite Fred Astaire—came to Las Cruces and decided to build a hotel there. (Sr. Rodríguez’s father had been president of Mexico, then governor of Baja California, and had, in the process, collected considerable wealth and Baja real estate.) Serving as his own architect and interior decorator, Rodríguez built a low, sprawling building in the villa style with wide terraces, airy loggias, fountains, a swimming pool, tennis courts, a trapshooting range, and a putting green. The rooms—there are only twenty—have stone fireplaces, and all face the sea and the harsh profile of the deserted island of Cerralvo, twenty miles offshore, which seems to hang in the sky. The mood here is of quiet elegance. In the bathrooms, fresh cakes of Guerlain soap are placed daily (though the chilling sight of a scorpion scrambling up the wall reminds one that one is, after all, in the tropics); all fruits and vegetables are flown in from Los Angeles. Still, the place is remote. The hotel has a radio that can reach La Paz, but there is no telephone or telegraph service (a gasoline-driven generator provides electricity) and, when one is a guest there, one literally cannot be reached.

Rodríguez also built himself a large house at Las Cruces and, because there was none in the area, he built a handsome church (a priest flies in every other week to say Mass). Then, flushed with the success of his first resort, he went on to build two others—Palmilla, some distance to the south near the little town of San José del Cabo, and the Hacienda Cabo San Lucas, practically on the top of the peninsula. (At each of these places he also built churches, and Rodríguez today sees a symbolic connection between his three churches and the three original crosses at Las Cruces, and with the Trinity, and now says that having built his churches, he no longer worries about getting into heaven.) From a business standpoint, however, the two new hotels—both larger than Las Cruces—put Rodríguez into serious competition with himself. Guests were abandoning Las Cruces for the other places, and Rodríguez hit upon the idea of turning Las Cruces into a private club, “for members only,” which charged annual dues—a gimmick, needless to say, to insure Las Cruces a fixed income. Rodríguez dressed up his membership list with a number of movie stars, including Bing Crosby, who built a villa of his own and spends several months a year there, fishing and snorkeling, and Bob Hope, who has never been there at all.

The new status of Las Cruces as a club has had an off-putting effect upon prospective guests. Some people have got the notion that Las Cruces is now some sort of private estate belonging to Bing Crosby, and others, afraid of being turned away, no longer try to stay there. Their fears are unfounded. While it is “up to the discretion of the manager” whether or not a nonmember may stay at Las Cruces, the place is, after all, in business to make money; if rooms are available, the manager never says no. Also, though membership is “frozen” at a hundred and eighty members, there are plenty of vacancies. Dues are two hundred and forty dollars a year, and they entitle a member to stay at Las Cruces for ten days a year free of charge.

On the other hand, Americans who suffer from either the There’s-Nothing-to-Do or the There’s-No-Place-to-Go syndrome, should be discouraged from visiting Las Cruces. There is no place to go. Of the two kinds of fishermen—those who are serious fishermen and those whose wives think they are serious fishermen—Las Cruces is for the former. Some of the richest waters in the world lie offshore, teeming with sail-fish, marlin, albacore, roosterfish, and dorado.

At regular intervals, pods of whales swim into the gulf to mate, and manta rays the size of grand pianos flip their preposterous bodies in the air. But night life is nonexistent. There is excitement, of sorts—a bitter feud between Crosby and Desi Arnaz, another member (Crosby, they say, wants Arnaz expelled from the club), is always worth a few minutes’ gossip and speculation. Las Cruces is popular with men who fly their own planes because that remote landing strip is an excellent means for getting illegal goods from the United States into Mexico (the planes unload quickly at Las Cruces, then fly on to La Paz to complete their flight plans), and the clandestine flights arriving and departing are fine fodder for conversation. (Materials brought in this way—such as firearms for hunting trips—are generally for their owners’ use, and so the Mexican government, aware of the practice, looks the other way.) But the greatest asset of the place, for those who fancy it, is the isolation, that splendid quiet.

Outside the hotel door, not long ago, a local wren had built a nest in a hanging lantern and was attending to three hatchlings there. She thoroughly disapproved of the occupancy of the nearby room which she clearly regarded as her own. Each time the guest forgot her busy presence and let his screen door slam shut, she registered her displeasure by flying at his face, making provoked noises. One evening two guests sat on the terrace near her nest playing a quiet—very quiet—game of dominoes. Once they shuffled their dominoes too noisily, once more incurring one of her testy demonstrations. That quick-tempered little bird could symbolize how very, very hushed the life at Las Cruces is supposed to be.

Mazatlán—almost directly across the Gulf of California on the Mexican mainland—is something else again. The changes that have taken place in Mazatlán in recent years are awesome. The old harbor, which used to remind many people of a smaller Rio de Janeiro, has been decorated with advertising billboards; the water of the bay has achieved an evil color and, as the city has grown, something that looks and acts very much like smog hangs stubbornly in the air. Tourism—and Mazatlán’s reputation as a sport-fishing capital—has done this. The downtown section of the city has undergone a sad decay and, meanwhile, along the beach to the north of town a gaudy “strip” of hotels, motels, and “boatlets”—not unreminiscent of Las Vegas—threads its neon-flashing way. The “piano bar” is a device that is apparently much favored in Mazatlán, and each new hotel announces its piano bar in tones more strident than the last. In Mazatlán, too, it is possible to see, with great clarity, how very Americanized much of tourist Mexico is becoming. That new language which some have called “Spanglish” is widely in evidence; ask a question in Spanish, and you are answered in English, and vice versa. Prices for articles in shops are now quoted simultaneously in pesos and in dollars, which never used to be the case, and in all the restaurants the food—lamb chops in brown gravy, ham with pineapple slices—has become determinedly “American.” Where tortillas used to be served with meals, hard rolls are now offered. When asked for tortillas recently, the waiter looked dismayed, and the fiery salsa picante—sauce of green and red chilis—has disappeared from the table in favor of American catsup. At the same time, one observes Mexicans being served appetizing-looking dishes and suspects that the natives may be eating far better than the tourists who gaze glumly at their pallid potatoes.

Meanwhile, though Mazatlán itself may lack charm, there does exist a charming way of getting—and leaving—there, if one is not rushed and can take the time. A ferry makes leisurely and regular crossings between Mazatlán and La Paz, taking overnight to cross the Gulf of California. On a night that is clear and full of stars, with a sea crowded with phosphorescents—and followed by leaping porpoises all the way—this is a lovely trip. The boat leaves Mazatlán on Tuesday and Saturday nights, arriving in La Paz the following morning. From La Paz, sailings are Thursday and Sunday nights. The boat, owned by Balsa Hotels (who operate the sumptuous Presidente Hotel chain in Mexico), offers two classes of passage, and first class is luxurious—all staterooms with private bath—and the dining room and bar are so appealing that many passengers stay right there all the way across the Gulf, never visiting their staterooms at all.

Puerto Vallarta—as the crow flies, some two hundred miles south of Mazatlán—is another resort widely said to be “ruined.” It was the “new Acapulco” of ten years ago and, since then, has achieved international fame as the location used for the film Night of the Iguana, and as the place where none other than Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor have bought a house. If, however, Vallarta has been ruined, it has been ruined in a delightful way. It has grown, but it has grown—so far, at least—in an orderly fashion. The architecture has been kept simple and provincial, in keeping with the red-tile-roof feeling of the place. Though there is a new Hilton hotel, as well as a Presidente, there are still none of the monolithic, high-rise buildings that have marred the horizon of Acapulco. A new “Gold Coast”—a stretch of big, sprawling houses (built for costs of a hundred and fifty thousand dollars and up)—has been carved out of what, four years ago, was virgin jungle, but this development blends pleasantly into the landscape. There is a new road running south to the fishing village (and pretty beach) of Mismaloya, which, mountainside, has now become overgrown and softened with natural green. Signs of growth are everywhere, and everyone is building—demonstrating the Mexican builders’ ingenuity when it comes to tacking new rooms, even whole apartments, on to existing structures; where there was one house, now there are four or five. The foresighted Rosita Hotel, still only three stories high, has four floor-buttons in its elevator. The bar of the Oceano Hotel, the “in” meeting place at the cocktail hour, is a-rustle with unfolding blueprints and architects’ sketches. Suddenly, all the taxis in Vallarta are a citified yellow, and what the other day was a native cantina is now a discotheque (“A-Go-Go”) with psychedelic light and air conditioning. The old man who used to sell fresh peanuts on foot now rides about in a motorized cart. Big Greyhound buses lumber into town, and jets from Los Angeles land at the airport. And, though prices have climbed somewhat, Puerto Vallarta is still a tourist bargain. A room in a good hotel can be got for as little as eight to ten dollars a night, which is in pleasant contrast to Acapulco, where forty-five dollars a night is no surprise.

A great and continuing drawing card for Puerto Vallarta has been the possibility of the Burtons’ presence there. “They’re due in any day now—perhaps tomorrow,” one hears, almost daily. The rumor that the Burtons are due in momentarily has been responsible for any number of two-week vacations being extended to four or six, and every day or so, with predictable regularity, the false news that the pair have, in fact, arrived spreads up and down the beach. Actually, Mr. and Mrs. Burton visit Puerto Vallarta only rarely. Still, their big white stucco house, the Casa Kimberly (named after a brand of Mexican gin) remains a major tourist attraction.

Meanwhile, despite its rapid growth and a certain amount of commercialism that has crept in—to the distress of old Vallarta’s fans—Vallarta remains a cozy resort. Las Muertas beach is still the town’s communications center—there are no telephones—and all information is exchanged, plans are made, and invitations are issued from here. An hour’s speedboat ride away lies Yelapa, a grass-shack settlement, populated with colorful escapees from Greenwich Village and Haight-Ashbury, that offers a splendid white sand beach beyond which lies a freshwater lagoon, fed by a cascading river. And Vallarta continues to offer a number of small, intimate cafés and restaurants where everybody, very quickly, gets to know everybody else. One of the pleasantest of these is called Chez Elena. It requires a stiff climb up a steep hill to get to, but offers such delicious specialties as cactus and tortilla soup and other culinary inventions of the proprietress, a half-Mexican-half-American woman named Elena Cortes. Doña Elena, as she is called, is every bit as extraordinary as the food she prepares. A plump and forthright lady with salty opinions on nearly everything, and no shyness about expressing them, she sees to it that all her guests immediately get acquainted with one another, and then she regales them with stories—all of them hilarious, many of them ribald—of her own unusual past. “Her restaurant is a Happening,” someone has said, and that is as good a description of it as any. Drinks at Chez are free with dinner—a nice touch. And if the hostess takes a particular fancy to you, she may treat you to a dollop of a special aphrodisiac liqueur she keeps handy. The label on the bottle advertises that it “gives you that volcano feeling.” It does, too. No, Vallarta has not become another Acapulco yet—not quite.

Manzanillo, further down the coast, is too busy being a bustling commercial seaport to make any concessions to tourism whatever (the opposite of Vallarta, where almost everything seems designed to please the tourist), and its pretty harbor is marred by large oil-storage tanks, and not long ago, a rusty tanker spewed black smoke over the city night and day. Beyond the harbor lies the extensive Zona de Tolerancia (or “Zone of Tolerance”), as Manzanillo quaintly calls its red-light district, and when the ships come in, this is a very busy part of town. A number of miles outside town, two resorts—Las Hadas and La Playa de Santiago—have been built, and these have both found favor with Americans. These are, however, very American places which, if they didn’t happen to be in Mexico, could just as well be found on a sunny beach in Florida. Both are very self-contained places, dozens of miles physically—and many more emotionally—from any city. “It’s a place to come and relax and do nothing,” said a Las Hadas guest. “Go out in the evening? There just isn’t any place to go.”

One man’s paradise is another man’s anathema, but if one were asked to pick a favorite small, still-unspoiled beach resort in all of Mexico, one might choose Zihuatenejo, the little town whose name cannot be pronounced without sounding something like a sneeze. Zihuatenejo is nothing at all like what Acapulco used to be, either—nor could it ever become another Acapulco. It lacks Acapulco’s scale—that great bay, for instance (the best natural harbor in Mexico), the array of rocky hills, and the violent rocks of the Quebrada where the famous divers leap into the sea. Zihuatenejo’s landscape is subtler, more delicate and rounded. The beach is there, a sweeping arc of sand brushed by a gentle surf—and so is a degree of isolation. There are no telephones in Zihuatenejo and, though it is physically no farther from Mexico City than Acapulco is, there is no direct road—nor, one is assured, will there ever be one. (The city fathers of Zihuatenejo have tempered their cupidity with reason, and have decided to take advantage of the town’s remoteness.) One flight a day enters Zihuatenejo from Mexico City, and one flight a day returns—making use of a horrific airstrip which seems to be composed of jagged boulders. (The head of the airlines office in Zihuatenejo explained recently that because of the strip’s terrain he cannot let planes land or take off with a full-weight load of passengers. Once, however, when an unusually large number of people had to leave on the same morning, he did, against his better judgment, sell every seat on the plane. “I went to the beach with a bottle of rum and my pistol,” he said. “I drank the rum and waited for the plane to make it into the air. If that plane had crashed, I was going to shoot myself”—a noble gesture and very Mexican macho, if cold comfort to the passengers.

In Zihuatenejo, too, there is some place to go. One can go across the bay—by waving for a passing boat and persuading its driver to take you—to a little beach settlement called Los Gatos, where several small restaurants serve oysters, lobster, and clams pulled fresh from the ocean. (The restaurants are in friendly competition with one another, and if one restaurant doesn’t have the dish you happen to want, your waiter will run down the beach to another restaurant to find it for you.) After lunch at Los Gatos, there is swimming and snorkeling in the still-water beach—created, according to the local tale, by a Zapotec king for his favorite mistress; he built a barrier reef of huge rocks beyond the beach to give her a gentle pool to swim in. (One believes this story more readily than the one about the crosses at Las Cruces.) Also, in the town of Zihuatenejo itself there are several good restaurants, cafés and cantinas—and a handful of little shops.

There are a number of good hotels—intimate (none of them is large) rather than luxurious—tucked against the mountainside, overlooking the bay, in a natural garden of cactus, Judas flower, hibiscus, bougainvillea, and jacaranda trees, with large green parrots, which are quite tame, fluttering about. In return for reasonable rates, the hotels offer reasonably good food, service and conveniences. In one hotel, however, there was a plumbing novelty. Though the hotel had both hot and cold water, on one side of the corridor there was cold water only, and on the other side there was nothing but hot. The mischief—a crossing of pipes—was committed long ago, and has resisted correction since it is buried no one knows where under the tile and masonry. The irony was that the more expensive rooms, facing the sea, had guests complaining of icy showers; the less costly rooms, in the back, had an embarrassment of hot water—too hot, in fact, to shower in at all.

But it is not for plumbing perfection that one seeks out a place such as Zihuatenejo. It is, in fact, for the opposite—for a sense, real or imagined, of the undiscovered, the unexploited, the “untouristy.” And this, of course, is the quality which those who have found Zihuatenejo consider most precious and are trying hardest to protect. “I literally refuse to tell people where I go in winter,” one woman says. “Not even our dearest friends know about this place.” “I just couldn’t bear to see this place ruined,” another said, “another Acapulco. I’m just afraid that if people find out about this it will be simply overrun!” Well, for the time being, it can’t be. With only those few small hotels—and that airstrip—there is just no way for an overrunning throng of tourists to get there, and no place for them to stay. There are no Sun Valley condominiums, as yet.

Zihuatenejo offers a sense of the primitive, along with certain amenities, but for the intrepid tourist who insists on the elemental, with only the barest of comforts provided, two other small towns on Mexico’s west coast ought also to be mentioned. They are Puerto Escondido and Puerto Angel, both in the state of Oaxaca, about halfway between Acapulco and the Guatemala border. Though the map indicates a road from Oaxaca City into each port, these roads are also for the intrepid; the trepid are hereby warned. (Local car-rental agencies will not rent you a car if they suspect you plan to drive to either of these places.) In both Puerto Escondido and Puerto Angel (the latter is a slightly larger town), there are fishing boats for hire—fishing and the beaches are the towns’ main attractions—but there are no hotels as such. There are, however, small posadas which are actually little more than rooming houses. Advance reservations at these hostelries are next to impossible to get (Puerto Angel installed its first electric lights only a year or so ago), and the best advice for an arriving visitor comes from a Mexican: “Whenever you arrive in a new town in Mexico, and are looking for help to find a place to stay, just go to the main zocalo in the center of town, and sit on a bench there. Pretty soon, within half an hour or so, someone will come along who will be able to help you.” Like so many odd facts about this smiling, improbable country, this one turns out to be absolutely true.

From the west coast of Mexico one can fly east to Cozumel and Isla Mujeres, two of Mexico’s Caribbean islands that are promoted as still “unruined.” Cozumel, the larger of the two, is where Jackie Kennedy Onassis has stayed, and this gives one an immediate idea of the decorous gentility of the place, quite a different mood from that of Puerto Vallarta (a raunchy mood set by Elizabeth Taylor). Everyone is very dressy in Cozumel. Men wear jackets and ties at dinner, and the women, in pearls and cashmere sweaters from Peck and Peck, sit about conversing in low, cultivated voices over bloody marys. The hotels—there are several, all large, modern, and expensive—are marbled, air-conditioned, and antiseptic. The east coast also lacks the landscape of the west coast—all those plunging mountains—and is flat for almost its entire length. On the other hand, the water of the Caribbean is calmer, bluer, and clearer—with excellent snorkeling and skin-diving. From Cozumel, too, there are side trips into the Yucatán wilderness. There are the cenotes, curious geological features of the area—wide, circular wells, often so symmetrical that they look man-made, which suddenly open up in the jungle floor, and which contain deep, sunken pools of black water. A cenote was first an underground cavern, or dome, formed by water erosion of the limestone which forms most of Yucatán’s substructure. Eventually, after enough erosion, the top of the dome collapses, leaving a mysterious-looking round hole. The Mayans believed that these eerie holes were sacred to the rain god, and when he seemed to need appeasing, virgins were dropped into the cenotes until rain came. Also, a few air miles down the coast and across the Yucatán Channel from Cozumel, the ruins of the ancient Mayan city of Tulum can be visited. The tombs, temples, and pyramids here are interesting because they are among the few remaining in Mexico that have not been restored. They lie untouched, just as they have lain for hundreds of years, high on a bluff overlooking the sea with the green and steamy jungle pressing around them.

At Cozumel, too, the conversation tends to run to how long it will be before this is “another Acapulco,” and “ruined.” Everyone has his favorite estimate—two years, three years, and so on. Heads shake and tongues cluck as prices inch higher. There has been a small exodus of sorts from Cozumel to Isla Mujeres, a twenty-minute plane ride to the north. But Isla Mujeres (which means “Island of the Women”; Cortés, they say, landed there and found only women on it, but no explanation for their presence there) is merely a smaller version of Cozumel, and so a number have returned—taking comfort, perhaps, in the fact that an island favored by Mrs. Onassis cannot—not this season at least—be completely vulgarized.

But in the meantime, where is the Acapulco that was? Perhaps the curious combination of elements that is responsible for what is present-day Acapulco cannot exist anywhere else—the combination of the beaches, that magnificent bay, the sheltering mountains, the soft, warm, still, moist air that has made Acapulco from the time tourists first started going there a particularly—there’s no other word for it—a particularly sexy place. That has always been Acapulco’s special quality—brown-skinned young men and women half-naked in a pool that has underwater bar stools, couples embracing each other on the sand, clinging to each other on the dance floor. Acapulco is like a large, very classy bordello, with the atmosphere of sex so thick you could cut it with a butter knife and spread it, like caviar, on canapés. Sex and personal indulgence—a place where, you are sulkily told, Merle Oberon—the town’s leading hostess, as everyone in the world must know by now—has a dressing room bigger than her husband’s bedroom, and where somebody else has perfumed water in all the toilet bowls. It is the hot, damp air that helps do it—air trapped and pocketed by the green encircling mountains and floating steamily from heated swimming pools and saxophones.

But there is something else that may be what Acapulco was. It is a great stretch of beach that lies about sixty miles to the north of Acapulco, just south of the little town of Petatlán. The mountains come to a thundering point here, then cascade down. The Pacific comes thundering in, dashes against rocks, then subsides against miles of sand. Flying fish flash against the sky. It is a long climb down the rocks from the road to the beach, but worth it. The place is called Playa del Calvario—perhaps because the promontory of rock that addresses the beach reminded someone of Calvary. In any case, in the amphitheater between the sea and the outlying arms of rock there is the same warm, moist, sexy air. There is no town here, no buildings—nothing. But perhaps some such lovely, lickerish Eden as this was what Acapulco was before anyone came there—anyone at all.