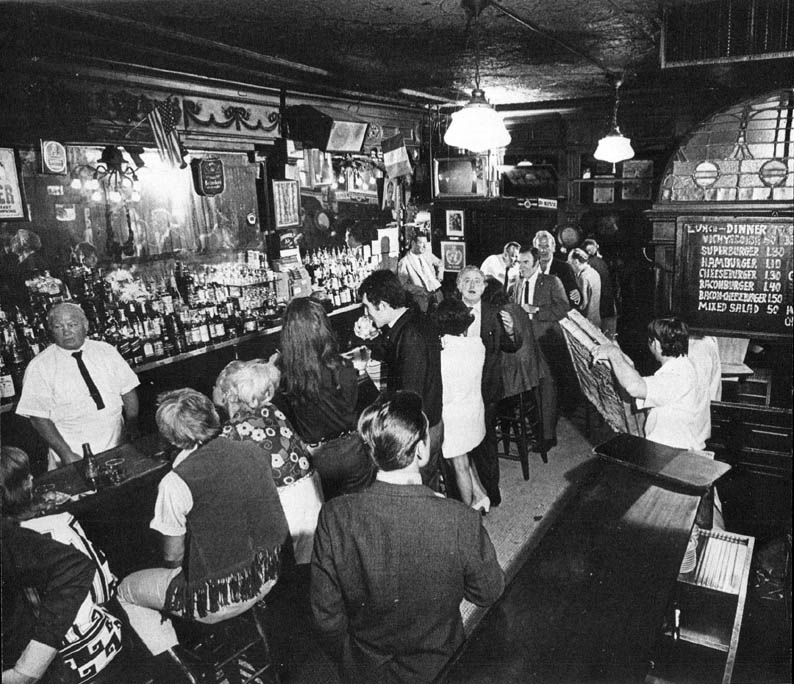

Photo by the New York Times. Courtesy of P. J. Clarke’s

A quiet night at P.J.’s

New York, N.Y. 10022: Indestructible P.J.’s

Meanwhile, in thoroughly spoiled New York City, as everyone knows, it is no longer chic to be elegant. The wrong places of yesteryear are becoming the right ones of today. That is, anything that is not somewhat disreputable is presumed to be somehow impertinent, and this supposedly accounts for the decline of, among other things, New York’s “pretty” restaurants—the closing of the Colony, Le Chauveron, the sudden abysmal emptiness of the Four Seasons, the rapid fall from grace of Raffles. Consider, on the other hand, the saloon at the corner of Fifty-fifth and Third which has just completed the most successful year in its eighty-year history, and is a happy gold mine for all concerned. “This place,” confides the slender young man with the over-the-ears hair to his blond ladyfriend in the knitted skullcap, “is perhaps the place in New York. You won’t find anything like this in Altoona. Down there, that guy in the blue sweater is what’s-his-name of the New York Knicks.”

What’s-his-name of the Knicks, seated in display position at the corner of the bar, is surrounded by kids, many of whom cannot be of legal drinking age but who are drinking beer nonetheless. He displays the easy grace and confidence of a star among fans, grinning at the kids’ questions and shrugging off their “oh, wows.” What’s-his-name is not a regular, but drops in occasionally because he’s sure to be recognized. Down at the other end of the bar, near the garbage cans, sit two regulars, a pair of ladies whose favorite topic of conversation is New York under Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia. Tonight, they are discussing what has happened to the subway fare since La Guardia’s day. The regulars sit at this somewhat less appetizing end because there is a better chance of seats here. It is five o’clock, and the place is filling up again after the brief post-luncheon slump. Outside, the city is a mixture of rain and unsatisfactory air, and the Third Avenue bus stop on the corner is disgorging passengers headed for the swinging doors with the cut-glass panes. Inside, against mirrored walls that are not only flyspecked but in desperate need of resilvering, the decor consists largely of signs which warn against the danger of overcrowding, the management’s lack of responsibility for lost articles, the fact that minors will not be served, that tax is included in the price of each drink, that gentlemen without escorts might think twice before coming here to meet other gentlemen without escorts. Over the bar hangs a sign that says, “BEER—THE BREAKFAST OF CHAMPIONS.” A vase of plastic lilacs blooms among the bottles. “This is really New York,” says over-the-ears-hair solemnly.

He may be right. As the hour approaches six, the noise level reaches din proportions, with Joan Baez contributing lustily from the jukebox. Rocky Graziano—a regular—has just arrived with Jake Javits, and is moving along the bar greeting friends with “Hi, guy!” (They call him “the Thespian” here.) At one of the corner tables, Bobby Short is showing off his new fur-lined overcoat. “Something gorgeous happens when I put this on—watch!” he burbles, putting on the coat and briefly parading the gorgeousness. A blond young woman enters carrying an ocelot on a leash. The place frowns on pets, but the young woman explains prettily, “He’s just like a little putty-tat,” and is allowed to stay. What at first appears to be a tiny child has just pushed through the cut-glass door, but it is quickly clear that she is a midget with a five-year-old’s body and a rather pretty fortyish face. She is apparently known here, for a chivalrous male patron hoists her by the armpits onto a bar stool, a position she could not achieve unaided.

But the clientele is not composed just of oddities and celebrities and put-ons. There are also intense young men in J. Press suits with skinny briefcases, silver ID bracelets and gold wedding bands, waiting for wives or girl friends and discussing parking places. Hairy, bearded types in denim jackets and beads and boots glare truculently at one another and talk sporadically of Film. A very pretty airline stewardess wearing a diamond wedding band flanked by sapphire guards is explaining to three very interested young men the availability of free passes to exotic ports on her carrier. She seems to suggest that these passes could be theirs for the asking. Behind a counter in the corner, a short-order cook is setting up his grill for hamburgers, lining up his bags of buns, bottles of catsup, and plates of onion slices in neat rows. Behind the bar, the two bartenders are shouting jovial obscenities to one another as they work, epithets accompanied by appropriately indelicate gestures. Two off-duty patrolmen are in earnest conversation (this is, after all, an Irish bar, and the Irish have always had the Police Department in the family), interrupted by a drunk who keeps tugging at their sleeves, trying to tell them something. The drunk speaks in syllables, but the syllables do not form words in any recognizable language. (“There’s a medical term for that,” one of the bartenders explains to a customer. “Brendan Behan used to get that way in here after he’d had a few.”) The policemen shuffle their feet in the sawdust on the floor, in embarrassment or perhaps to keep warm; this saloon, perhaps because it encourages the consumption of alcohol, is drafty and underheated. Through it all, via another swinging door, there is a frank and unlimited view of the men’s room that opens, closes, and opens up again. To anyone who giggles over this circumstance—or who, heaven forbid, protests—the bartender’s reply is “Them that’s proud never complains!” It is, in other words, a typical evening at P. J. Clarke’s, the pub where the primary rule is never be surprised at anything.

There are one or two other rules—unwritten, of course. For example, one is not supposed to enter P.J.’s expecting such a queer reward as solitude, or even privacy. P.J.’s is a determinedly social saloon, and anyone standing at the bar is expected to engage in lively conversation with whomever he is standing next to. Nontalkers are frowned upon, sometimes even asked to leave. Not long ago an uninitiated customer had the poor taste to bring out a paperback book and start to read it at the bar. The bartender’s reaction was swift and decisive. “If you’re going to read,” he announced, “go on down to Tim Costello’s. That’s where all the goddamned intellectuals hang out!”

At the same time, P. J. Clarke’s customers are expected to take the unexpected in their stride. One is not supposed to react to the sight of the famous blue eyes of Paul Newman across the room, or to Mr. and Mrs. Aristotle S. Onassis dining quietly at a corner table. Arlene Francis and Martin Gabel are regular customers, as are Artie Shaw, John Huston, and Mayor John Lindsay. Nor was anyone particularly surprised to read, among the 1971 findings of the Knapp Commission, that P. J. Clarke’s was the payoff spot where two men—one of them a police officer—negotiated the price that would allow a lady with the unlikely name of Xaviera Hollander to continue operating one of the neighborhood’s glossier brothels (specializing in kinky sex) free of police harassment. (Mrs. Hollander’s price for peace, according to tapes from the bugged P.J.’s bar, was twenty-one hundred dollars in three installments.) This was regarded as simply another aspect of P.J.’s raffish charm. “They always did get a lot of gamblers and racketeers and crooks up there,” sniffs Fred Percudani, bartender at the rival Tim Costello’s down the street. “Here, we attract more of an executive-type crowd.”

P. J. Clarke’s is possibly the only saloon in town where the jukebox offers the latest hit by Melanie as well as “Paper Moon” as selections. (Tim Costello’s provides discreet radio music from WPAT.) When, for reasons that have never been quite clear, a definitely non-executive type named Lawrence Tierney found his head involved with one of Clarke’s old-fashioned ceiling fans, nobody thought a thing about it, not even Mr. Tierney, who not only announced that he would not sue anybody for the lacerations incurred in the encounter, but apologized, and offered to have the fan repaired. When, after a particularly bibulous evening, a well-dressed young couple lay down on the dining room floor and went to sleep, no one paid them any heed except for Eddie Fay, one of Clarke’s ex-wrestler bouncers, who gently tried to coax the pair back to consciousness with cups of strong coffee. About a year ago, two men wanted by the FBI on narcotics charges were arrested while relaxing at P. J. Clarke’s. A few months later, Clarke’s became the first Third Avenue saloon to be the subject of a snooty New Yorker cover. And through all these varied goings-on P. J. Clarke’s customers rejoiced in the knowledge that their favorite watering hole has achieved something of the status of a New York monument, that it will now in all likelihood remain at the corner of Third and Fifty-fifth for as long as the Statue of Liberty remains in New York Harbor. As the sole holdout in the block otherwise occupied by a new forty-five-story Tishman tower, Clarke’s is a nineteenth-century anachronism, a dowdy oasis in a street of tall steel and glass. Clearly, shabbiness is not only chic but offers a kind of passport to immortality.

The success and survival of P. J. Clarke’s make, as the Irish say, a tale to tell, and from the beginning involved an uncommon combination of fiscal wizardry and Old World witchcraft. Patrick Joseph Clarke was a dead ringer for Admiral Bull Halsey, and his conversation consisted mostly of grunts. Apprenticed in the old country, he was a strict saloonkeeper and when he opened his place in 1892 there was no nonsense allowed. Woe betided the waiter who failed to put his tips in the kitty, or the bartender who tippled from Paddy Clarke’s stock. It was he who established the anti-intellectual cast of P. J. Clarke’s. Some said this was simply because his chief rival, Tim Costello, courted the writers and artists—Hemingway, Thurber, Steinbeck, Robert Ruark, and John McNulty. “Pansies and willie-boys!” Paddy Clarke called them, and that was that. A bachelor, he was pious and churchgoing, and also strongly superstitious. During Prohibition (“It’s like a bad cold, it will go away,” he used to say) he was once badly beaten by thugs, and his relatives began urging him to write a will. But Paddy Clarke was convinced that if he wrote a will he would surely die the next day. And so, with his fingers still crossed against the morrow, he died intestate in 1948.

It was this single fact, ironically enough, that set the course of Clarke’s saloon toward becoming an unofficial city landmark. (A spokesman for the Landmarks Commission has said that Clarke’s architecture is not sufficiently distinguished to warrant making it an official landmark, as though Clarke’s customers could possibly care.) Because when Paddy Clarke died with neither direct heirs nor a will, all his relatives—brothers, sisters, nieces, nephews, both here and abroad—fell to wrangling over who should receive which share of Paddy Clarke’s estate, the most important part of which was the building with the bar downstairs and three floors of cold-water flats above. Visions of wealth and the easy life danced in the eyes of all the relatives, particularly those back home in County Longford where exaggerated reports of Paddy’s wealth had filtered. But when the relatives could not agree—and there is bad feeling between a number of Clarkes today over the matter—the court ordered that the building be sold. Thus it was acquired in 1949 for thirty-three thousand dollars by a young man named Daniel H. Lavezzo who, with his father, had been running a business importing Italian antiques, but who had also made a profitable sideline out of dabbling in real estate properties, particularly those in somewhat rundown neighborhoods.

From the beginning, Dan Lavezzo admits that he had no consuming interest in being a saloonkeeper. But he was interested in making money and so, since he was now running a saloon, he decided to run a profitable one. Clarke’s had already acquired a reputation as a popular spot for society and show folk, in a day when debutantes and Park Avenue blades considered it fun to go “slumming” in the slightly dangerous shadows of the old Third Avenue El. Two movies—The Lost Weekend and Portrait of Jennie—had used Clarke’s, or a reproduction of it, as settings. And it had become increasingly a place where out-of-towners headed when they wanted the feeling of rubbing shoulders with the greats of Manhattan, even though, in most cases, the out-of-towners just rubbed shoulders with one another. Because it was also a popular bar with the police force, Clarke’s customers also enjoyed the feeling that they were rubbing shoulders with men whose exciting task it was to deal with crime. The occasional presence of a lady no better than she should be was merely titillating, particularly when she was balanced with a diamond-encrusted Hope Hampton or a Barbara Hutton. Lavezzo determined to change as little of this ambiance and clientele as possible, and went about the task of preserving Clarke’s special Irish flavor with a fine Italian hand.

He installed Charlie Clarke—P.J.’s favorite nephew—as his general manager. Charlie, who had been born in one of the flats upstairs, and who had been a popular waiter and bartender for his uncle, gave the place a valuable aura of family continuity that kept the old trade from straying elsewhere. When Glennon’s Bar & Grill, competition from across the street, was forced to close by a landlord who wanted to sell the building, Dan Lavezzo hired Jimmy Glennon, the popular bartender, and brought him—and his customers—over. (For years, Glennon has been writing a book: How to Be an Irish Mother.)

By the mid-1950s the El was down, and Third Avenue had begun its renaissance as a street of glittery skyscrapers. Advertising agencies and publishers and film companies abandoned Madison and moved to Third, bringing with them new customers for P. J. Clarke’s. In 1955, Dan Lavezzo bought three small two-story rooming houses behind Clarke’s on Fifty-fifth Street, broke through into them, and added the back dining room, which, because it was darker, cozier, and slightly less noisy than up front in the bar, quickly became the most “exclusive” dining area.

Lavezzo had been living in Greenwich, but when the State of Connecticut gobbled up his property to make way for the New England Thruway he needed, for tax reasons, to spend the money realized from the sale of the Greenwich house on another residence. At the time, the flats in the two top floors above Clarke’s had been condemned, and so Lavezzo decided to throw these tiny flats together into two large apartments, one to a floor. The third floor thus became bachelor quarters for Dan Lavezzo, who is divorced, and the top floor became an elegant pad for Michael Butler, the millionaire sportsman and producer (Hair and Lenny). The second floor, meanwhile, housed the Lavezzo antique business, which was taking increasingly less time than the real estate and restaurant business. This was the state of affairs when the Tishman Realty and Construction Company, which has been responsible for some of the city’s more monolithic structures, announced plans to build 919 Third Avenue, which was to occupy the entire east side blockfront between Fifty-fifth and Fifty-sixth streets, including P. J. Clarke’s. The interests of the Tishman brothers and Daniel H. Lavezzo were about to collide.

Robert Tishman, who heads the construction company, has a reputation of driving a hard bargain. “He is one tough cookie to deal with,” says Lavezzo, with more than a touch of respect in his voice. So, though on a smaller scale, is Danny Lavezzo. “He is a very sophisticated trader,” say the Tishmans. Lavezzo, a compact, wary-eyed man in his early fifties, has the air of a man not easily persuaded to do anything he doesn’t want to do. Though he has been known to consume as many as fifty beers a night at P.J.’s—“I never drink the hard stuff on the job”—Dan Lavezzo is known as a hard man to catch off guard. He was not at all anxious to sell his building to the Tishmans, nor to lose the one-to-two-million-dollar-a-year business which his building was then providing. “There’s a lot of superstition in this business,” Lavezzo says, “and most guys who run a successful joint believe that it’s bad luck to move. If things are going good, you don’t even fire a busboy—much less go to a new address.” Clarke’s to be Clarke’s, had to be at the northwest corner of Fifty-fifth and Third.

Dan Lavezzo also owned a building in the middle of the block that the Tishmans wanted and which, because of its central position, was even more pivotal to their plan. This gave Lavezzo the upper hand. And so, after a battle of nearly two years’ duration, during which negotiations broke down several times, Lavezzo and the Tishmans reached an agreement. Lavezzo would sell both Clarke’s and the second building to the Tishmans. The mid-block building would be razed to make room for the tower, but Clarke’s would be permitted to stand untouched and, as a guarantee, Dan Lavezzo was given a ninety-nine-year lease on the property as part of his price. In the deal, a figure of somewhere in the neighborhood of one million dollars went to Lavezzo for the air rights above his store—or not a bad appreciation on his original thirty-three-thousand-dollar investment. Other restaurateurs in the city turn positively glassy-eyed with jealous admiration of Lavezzo and his feat. “The monumental chutzpah of the man!” cries Vincent Sardi. Lavezzo, typically, just shrugs it off. “Air rights? Air rights?” he asks innocently. “I don’t remember anybody talking to me about air rights.” “He’s putting you on!” snorts Jerry Speyer, a Tishman vice president and Robert Tishman’s son-in-law. “He knows goddamn well what he got for the air rights.” Also as part of the deal, because of a complicated zoning conflict between commercial and residential properties, the top two floors of Clarke’s had to be lopped off, forcing both Messrs. Lavezzo and Butler to find new apartments elsewhere.

It was not the first time that an old-shoe neighborhood bar had had a modern tower built around it. Hurley’s, for example, has been contained within the Rockefeller Center complex, and just down the street on Third Avenue, Joe & Rose’s Restaurant is presently being encased in a huge new office building. But, because the architects at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill felt that Clarke’s was something of a special place, they designed a handsome courtyard around it, to set it off a bit, and then placed 919 Third Avenue several yards behind the regular building line to even further set it off. The Tishmans offered to lease part of this new plaza to Lavezzo for an outdoor café, but Lavezzo turned them down. The Tishmans are still somewhat disgruntled about that. After all, what realtor likes to see some of his property untenanted? But Dan Lavezzo thinks little of outdoor cafés in New York. “You get dust and soot in your potatoes,” he says, “and some bum can spit at you or try to panhandle you, or make a remark. Listen, if I was up on Fifth Avenue with a view of the Park, that would be something else. But I’m on Third with a view of the back door of the Post Office.” Michael’s Pub—in a new location in the Tishmans’ building—has set out umbrellas and tables and chairs in front of its share of the new plaza. Lavezzo doesn’t think they add much. “Clarke’s has always been an indoor sort of place,” he says. “People come here to get away from the streets and the traffic and the crummy people.” Lavezzo is prouder of the hospitable new bike rack that he has set up behind his saloon, and of the handsome new row of globe lights along his outside wall. The other night, while customers stood in line for tables at P.J.’s, Michael’s Pub next door was achingly empty, its bartender engrossed in the Racing Form.

In Paddy Clarke’s day, Irish bars like his along Third Avenue served free meals, usually a thick soup or a stew, with their drinks, but Dan Lavezzo brought in a simple but reasonably varied menu of dishes for which the best adjective would be honest. What was formerly the free lunch counter next to the bar is now set up to serve what Clarke’s regulars agree are some of the best hamburgers and chili in town, and the food in the dining room is—considering the tiny kitchen from which it emerges—very good indeed. Chalked on a blackboard, the bill of fare includes such items as steak Diane, meatballs with chili, and zucchini Benedict, which means with hollandaise sauce. Not long ago, Dan Lavezzo was tickled to receive, from a friend returning from France, a menu from a fashionable Paris restaurant which listed “spinach salad à la P. J. Clarke’s”—a salad of tossed spinach greens and fresh white mushrooms—and he is still proud of the fact that in 1966 Craig Claiborne of the New York Times gave his restaurant a rating of three stars. (“Not bad for a corner saloon,” he says.) There is also an extensive and reasonably priced wine list. Dinner for two, with drinks, can be had for under ten dollars.

There are other Lavezzo touches—such as the fact that virtually the only advertising he has ever done has been to print the name of the place on matchbooks and sugar cubes. (As a favor to his friend George Plimpton, Lavezzo runs an ad in the Paris Review consisting only of P.J.’s telephone number.) Also, his is one of the few remaining bars in New York that still serve real ice cubes in the drinks, and not the slivered machine-made wafers that have melted almost before the drink reaches the table. Then there are the huge, old-fashioned porcelain stanchions in what is the town’s most public men’s room—nicknamed “the Cathedral” because it is surmounted by a vaulted Tiffany glass ceiling—into each of which is placed, each evening, a block of icehouse ice. One customer, apparently unused to such amenities, emerged from the Cathedral not long ago carrying one of these blocks of ice and asked the bartender for “some Scotch for this rock.” Then there is Dan Lavezzo’s standard of service, which he likes to be prompt, polite, but informal and unfussy. To help achieve this he pays his waiters, who work in white shirtsleeves and aprons, on the scale of bartenders.

Dan Lavezzo is distrustful of publicity, and such as P. J. Clarke’s has had has been self-generated, with no assistance from its proprietor. He reacted “with resignation” to the printed reports from the Knapp Commission hearing about Clarke’s being a police payoff station. “What the hell can you do?” he asks wearily. “Everything goes on at a bar.” And why, he wonders, did the D.A.’s office wait until the two men it wanted had wandered into P. J. Clarke’s for a drink before making their arrests? The officers, it turned out, had been following the pair for weeks. Was there a touch of press-agentry in the federal agents’ decision to make their big move in a famous and conspicuous place? And Lavezzo is cynical about the press itself. “If something bad happens here, the papers are always sure to spell your name right,” he says. But if the Daily News runs a picture of Ari and Jackie Onassis coming out of here, the caption will say they’re leaving ‘a Third Avenue saloon.’”

Too much publicity of any kind, Lavezzo feels, can be bad for a place like his, particularly in a city like New York where things go out of fashion almost before they’re in. “Look at the places that were big a few years back,” he says, “the places that were all over the papers like the Peppermint Lounge, Arthur, Le Club, Hippopotamus—they’re all dead or half dead now. Look at Elaine’s. Nobody gets more publicity than she does these days. She’s got friends feeding items about her into the columns every night. But the trouble is she’s attracting all the sorts of people she didn’t want to have. And I’ve heard reports of rude treatment and bad service. There used to be a place up the street called Stella’s. Stella’s was the in place for a while, and Stella used to insult the women and grope the men. She got away with it for a while because people thought it was cute. But she closed up and moved to Florida a long time ago. If I were Elaine, I’d be very careful.”

Getting and keeping the right kind of clientele is, one gathers, something like performing a tightrope act. “I don’t want this to become a singles joint, like Maxwell’s Plum or those places up on Second,” Lavezzo says. Single girls in New York have long been aware that P. J. Clarke’s is not a promising hunting ground for men. Two pretty young magazine editors who had stopped by Clarke’s for beers during the evening rush hour were told, somewhat abruptly, by the bartender, “Look, if you two girls just came in to get out of the rain, don’t take up room at the bar.” And when, several years ago, Clarke’s began to get a reputation as a rendezvous for the gay crowd, Dan Lavezzo put up a sign saying that men unescorted by ladies can only be served at the far end of the bar. This sign hangs face to the wall on most “normal” evenings, but can be flipped around so as to state its business should the occasion demand. Lavezzo says, “We don’t want people to have too good a time here. We don’t want people singing or banging on the table, or getting too noisy or getting into fights. I have my two bouncers, Eddie and Mark, to take care of that sort of thing. The trouble is, you can’t rough people up the way you used to—if you do, they’ll sue. What we want is to keep this a nice, friendly place where people can eat and drink in a relaxed, homey atmosphere.”

For the most part, Lavezzo gets his wish, though there are occasional bad moments. There is one man, the bane of Third Avenue saloonkeepers, who goes from bar to bar trying to engage the customers in arguments. He will argue, it seems, about almost anything. When he appears, and becomes too belligerent, he is gently but firmly ejected from Clarke’s. Also—and members of the Women’s Liberation Front should take note—Clarke’s bartenders insist that they have much more trouble with disorderly women than they do with men. “A drunk woman is impossible,” Lavezzo says, “and you really have to be careful throwing them out.” For some reason, there is a curious witching hour in bars like Clarke’s. It occurs around 10 P.M., and is the moment when trouble starts. No one knows quite why, but bartenders heave a sigh of relief when ten-thirty comes, knowing that if a saloon can make it peacefully through that moment it will probably make it through the night.

And Lavezzo must be doing something right, because Clarke’s is nearly always thronged with people from the time it opens at ten in the morning until three or four the next, when it closes, seven days a week. If there are any complaints they are of crowds at the bar and long lines waiting for tables in the dining room. Business has never been better, and Dan Lavezzo admits, “Now that we’re stuck out here like a sore thumb, people notice us who never did before. It’s the best advertising we could have.” He has been gradually phasing out his upstairs antiques business, and would like to open another dining room on the second floor. The new dining room would be, according to Lavezzo, “a little more elegant, maybe, but still P. J. Clarke’s, still the nineteenth-century feeling. I’d have no trouble filling it.” His plan, however, has presently run afoul of his new landlords, the Tishmans. To accomplish it, Lavezzo feels that he would have to expand his kitchen facilities in the basement, including some space that belongs to the Tishman tower. Because of an existing contract with another restaurant owner in the building, the Tishmans say they cannot legally rent Lavezzo the space. At the moment, matters are at a standstill.

Paddy Clarke was a great lover of animals, and in his day, there was always a dog, or sometimes two, around P. J. Clarke’s. (Even today, dogs have a better chance of getting into Clarke’s than ocelots.) One of Paddy’s dogs was a habitual wanderer, and became well known around the East Side—so well known that cab drivers, spotting him on his rounds, would pick him up and drive him home to Clarke’s, always certain that they would be paid their fare. Another dog, patently female, was named Bobo Rockefeller, after a favorite Clarke’s customer. All these dogs were known and loved by Clarke’s regulars, but the old-timers agree that there was never a dog quite like the one Paddy Clarke named Jessie. Jessie, according to Paddy, was a “Mexican fox terrier,” but whatever she was she was an extraordinary person. If you gave Jessie a nickel she would trot across the street to Bernard’s drugstore and buy a chocolate bar. She would return to Clarke’s with the chocolate bar and nudge you to unwrap it for her. If you gave her a quarter, she would go in the other direction to a meat market, and there she would purchase a bag of dog scraps. Paddy Clarke used to insist that at the end of the day she collected his bar receipts and helped him check them against the chits. She was the official screener of Clarke’s customers. If Jessie growled when you came through the door, you could not be served.

When Jessie died, Paddy Clarke had Jessie stuffed and placed in a position of honor, on a shelf just above the entrance to the ladies’ room. Only slightly the worse for time and dust and smoke and a few moths, she is still there, as immortal as Clarke’s itself, a mascot and a symbol. She still wears a savvy expression, keeping a beady eye on things. Isn’t it pleasant to think, in this age of instant self-destruct mechanisms, that thanks to Danny Lavezzo’s ninety-nine-year lease, Jessie will still be there in the year 2066, by which time there will surely be saloons on the moon. So will P. J. Clarke’s still be there, indestructibly dowdy, triumphantly tacky. If Patrick Joseph Clarke had made a will, the way everybody had wanted him to, who knows what might have happened to his bar and grill? As it is, it would seem that only an act of God could remove P. J. Clarke’s from the corner of Fifty-fifth and Third. And God, in most cases, was on Paddy Clarke’s side.