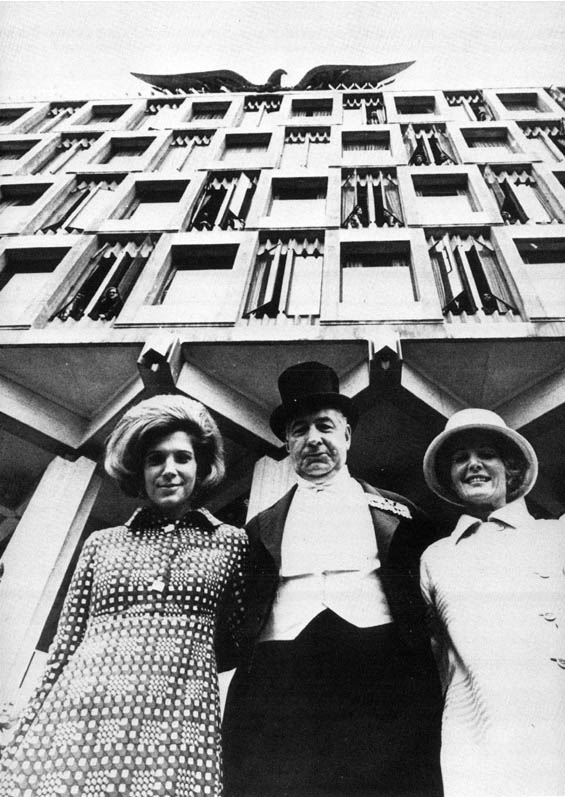

United Press International Photo

The Annenbergs at peace with the Embassy eagle. (Mrs. Annenberg’s

daughter, Mrs. Wallis Weingarten, at left)

London: His Excellency, the Ambassador

Eero Saarinen, in an institutional mood, designed the United States Embassy which occupies the entire western flank of London’s Grosvenor Square. “Occupies” is the right word. The huge structure, of glittery Portland stone and glass, is certainly out of harmony with its neighbors, all stately Georgian mansions of mellowed brick, and the British, who relish nothing more than criticizing American taste, have made the building the subject of attack ever since its completion in 1960. Vulgar Americans have been taken to task for “spoiling” London’s loveliest square, and the Embassy façade has been likened to everything from a recumbent air conditioner to the grille of a giant Edsel.

A feature of the design is an enormous eagle, as big as a World War I biplane, which perches on the roof and which seems about to sweep down on all the pigeons in the park (who, with pigeon-like perversity, ignore the threat and line up along the eagle’s broad wingspan). And, to the British critics, this monster bird represents American aggression from 1776 to our present involvement in Vietnam. Thus it was when Walter H. Annenberg, the Philadelphia communications tycoon newly appointed United States ambassador to Great Britain by President Nixon, announced, in all innocence, that one of the first things he intended to do in office was take the eagle down.

His gesture, obviously, was meant as one of goodwill to the British critics. What ensued, however, was the first of a series of tempests in English teapots, large and small, that have made Ambassador Annenberg the most controversial and most criticized ambassador to Britain since Joseph P. Kennedy. Once more a rich man seemed not to know how to do it.

Immediately, art and architectural groups flew to the defense of the building, the eagle, and the ghost of the late Mr. Saarinen. The eagle, they pointed out, was an integral part of the building’s total concept, had been commissioned and approved by Saarinen himself, and could be stripped off the top of the building only at great aesthetic peril. The eagle’s sculptor, Theodore Roszak of New York, cried out that any attempt to tamper with his eagle would be a violation of the First Amendment by denying an artist his freedom of expression. Various congressmen, meanwhile, pointed out that Mr. Annenberg had grossly overstepped his authority. It is not up to an ambassador to make architectural decisions about public buildings, including embassies, which are the property of American taxpayers. Senators who had been opposed to the Annenberg appointment to begin with muttered darkly that he would be lucky if he got to choose the color of the carpet in his office, much less tear down eagles. Senator Karl Mundt, in an attempt to make light of the matter, announced that he would agree to the removal of the eagle if, in return, the Queen would take down the pair of lions that guard the entrance to the British Embassy in Washington. Finally, admitting that he had spoken unwisely, or at least naïvely, Mr. Annenberg announced that he and the eagle had arrived at “a firm and friendly understanding,” and that “the eagle speaks no ill of the Ambassador, and the Ambassador speaks no ill of the eagle.”

For years, it has been standard American political practice to appoint wealthy men to prestigious diplomatic posts in glamorous European capitals. These appointments are given out, as everybody in the world realizes, as rewards for generous political contributions. London’s American Embassy is one of the right places where a rich contributor to a winning presidential candidate can expect to find himself. It has been a long time since such men as Benjamin Franklin, the first Minister Plenipotentiary from the American States to France, have been expected to have real diplomatic training and the power to negotiate important treaties, sign world-shaping documents, or even remove mighty eagles from their perches. Today, with such men as Mr. Henry Kissinger roaming the world on vital and secret missions, the role of American ambassador has shrunk to that of a social functionary with little more to do than make friends and shake hands and smile for photographers. Clearly, to President Nixon, Walter Annenberg was one of the right men for one of these socially and politically right posts. Then why did he seem, all at once, so inexcusably wrong?

It was probably Ambassador Annenberg’s naïveté and newness at his job that caused his subsequent embarrassments and predicaments, and that were responsible for the fact that during the first six months of his tenure he was the unhappy recipient of a perfectly terrible press, particularly in Britain. He had never claimed to have any great diplomatic experience and, for a while, to newspaper readers and television viewers, this seemed almost painfully apparent. As he was getting his feet wet as our ambassador to the Court of St. James’s, he kept putting his foot in it, again and again.

To begin with, there was the episode of his presenting his credentials to the Queen, an event which was immortalized on television film. What happened was that the Queen asked him, “Are you living in the Embassy?” The Ambassador’s longwinded reply was, “We are in the Embassy residence, subject of course to some of the discomfiture as a result of the need for elements of refurbishing and rehabilitation.” Ambassador Annenberg had no sooner uttered these words than the British press leapt upon them with wild little squeals of joy, sticking little pins into the ambassadorial syntax. The British, who have always felt that no one speaks the English language properly but a Briton, and certainly not an American, went to great lengths to point out that the noun form of refurbish is refurbishment, not refurbishing, and that rehabilitate means to restore to health. Had the Embassy residence been ailing? If not, Mr. Annenberg’s answer contained a pathetic fallacy. Did it all matter? To the British, apparently, it did, and for a while it seemed as though these would become the twenty-six most quoted—and misquoted—words in London.

No one, meanwhile, troubled to point out that the Queen had asked a particularly vacuous question, and might herself have been called guilty at least of having her facts wrong. “Are you living in the Embassy?” The Embassy in London is an office building and closes at 6 P.M. It contains no living facilities. The Embassy residence, a huge mansion originally built by Barbara Hutton for the second of her many husbands, is miles away in Regent’s Park, and was being refurbished—as Ambassador Annenberg was attempting to explain to Her Majesty.

Then there was the weighty matter of whether or not Mr. Annenberg’s daughter, Wallis (Mrs. Seth Weingarten of California), accompanied her father to the presentation ceremony. A reporter from the mass-circulation Sunday Express wrote that she did go along, and treated it as a gaffe of the first water, since for members of an ambassador’s family to accompany him on this mission is something “never done” in Britain. Immediately, everybody denied that Mrs. Weingarten had done more than wave goodbye to her father from the Embassy steps when he went to see the Queen. Ambassador Annenberg denied it (“Ridiculous!” he said), Mrs. Weingarten denied it, and Buckingham Palace denied it. Whether the Sunday Express made an honest error or maliciously made up the story, no one knows.

Ambassador Annenberg seems to share the Nixonian habit of over-explaining (“Let me make this absolutely clear”), a habit which can make each clarification of the issue at hand seem even cloudier. Thus, each time the story of Mrs. Weingarten tagging along to meet the Queen was denied, and the more her actual whereabouts during the ceremony were explained, the more the story spread and the more people began thinking that she did, even though she most emphatically did not.

Instead of letting his remarks to the Queen die a natural death in the press, Ambassador Annenberg has kept on issuing new explanations of why he made them, thus keeping the long sentence alive—to the delectation of reporters. “You must remember I had never met Her Majesty before,” he said. “I had never been inside the environment of Buckingham, and you must realize the impact of a thousand years of history. You must remember along with that I’m an inexperienced diplomat. I’m basically a businessman. So if you add all that together, all together in white tie and tails with your letters of credence, and the letters of recall of your predecessor, what could have had a greater impact on somebody, a neophyte in the arena. I’d never in my life experienced anything like it. I responded in formal terms to a formal occasion. Was I so wrong? I don’t reckon so.”

And Leonore Annenberg, his pretty blonde wife, added, “I think, and most of the people who remember it think, my husband carried off a difficult situation extremely well. And yet this remark keeps haunting us. It’s so unfair.”

What Ambassador Annenberg did not explain is that as a youth he suffered from a crippling stammer. It is only as a result of years of work, determination, and professional help that he is able to speak at all. He taught himself to speak by the arduous method used by, among other stammerers, the late W. Somerset Maugham. He composes his sentences—literally “writes” them—in his head before putting them into words. This is why his utterances so often have a stilted ring. The stammer still catches up with him at times, and his lips work to form words. The letter w is particularly difficult for him, and it is part of his training, not pomposity, that causes him to refer to himself using his full name—as he does when he asks, “Why do they write such things about Walter H. Annenberg?” Television cameras, as they do many people, cause him to freeze. Because of the stammer he will not conduct press conferences. Also, he has suffered all his life from partial hearing. Conversation—particularly the banal sort of social chitchat which is practically the only sort one hears in British Court circles (“Are you living in the Embassy?”) is an ordeal for him—and so meeting the Queen in front of a battery of cameras was, as no one knows better than his wife knows, a difficult situation carried off well.

But it was overexplaining again that got both Ambassador and Mrs. Annenberg involved in still another brouhaha with the press about, of all things, finger bowls. Someone quoted Ambassador Annenberg as saying that the former occupants of the residence, the David K. E. Bruces, “didn’t even” have finger bowls. The comment would hardly have created more than a bitchy column’s morning giggle if the Annenbergs hadn’t risen to the bait with another explanation. “My husband,” Mrs. Annenberg announced, “was merely observing to a few friends that certain dishes were used on certain occasions and casually observed that Mr. and Mrs. Bruce did not appear to have the proper finger bowls when we took up residence. Really! Does it matter?”

Well, now. The answer to her question might have been “No, it doesn’t,” if Ambassador Annenberg had not come forward with this explanation of his wife’s explanation. “We were merely intrigued,” he said, “at the British custom of serving finger bowls only after artichokes, asparagus, or fruit—rather than the American custom of serving them after every meal, which makes less sense.” “Those wretched finger bowls!” his wife cries. Quite clearly Mrs. Annenberg has been even more disturbed and dismayed by the hostile British press than her husband—and he has been disturbed and dismayed considerably.

What, then, is “wrong” with the Annenbergs as far as the British are concerned? Why have they seemed such a bitter pill for the British—particularly the perfumed circles of British upper-crust and diplomatic society—to swallow?

Walter H. Annenberg, at sixty-four, is stockily built with ruddy good looks, silvering hair, a hearty, meaty manner and a big handshake. Outwardly, he is an eager, friendly Saint Bernard of a man, but there is a steely glint in his eye that promises he would be a tough person to cross. His wife, by contrast, is coolly poised and looks very much like the actress Joan Fontaine. “When we heard Walter had been named ambassador, we all thought that it should have been Lee,” one of Annenberg’s sisters says. Leonore Annenberg’s diplomatic skills have been tested by the fact that when she married her husband—the only son out of a family of eight children—she acquired seven sisters-in-law. All the Annenbergs are extremely rich, and the family fortune is one of the largest in the world. The Annenbergs are so rich that none of them can say with any accuracy just how much they are worth, since the size of the fortune, depending on fluctuations in the stock market, the art market, real estate, and so on, rises and falls by tens of millions of dollars from day to day. “Let me just say that it is vast,” says Mrs. Leo Simon, one of Ambassador Annenberg’s sisters.

All the Annenbergs enjoy living on a grand scale, and a passion for building and decorating huge houses and apartments amounts to a family obsession. One sister, Mrs. Joseph Hazen, recently bought the twenty-seventh floor of New York’s Hotel Pierre—over the telephone. Someone told her she would like it, and so she bought it. Another, Mrs. Simon, has redecorated the large Fifth Avenue duplex that formerly belonged to Joan Crawford. All the Annenbergs have multiple addresses, with houses in New York, Westchester, Palm Beach, and Beverly Hills. Walter Annenberg has an estate on the Philadelphia Main Line and another, much larger, called Sunnylands, in the desert near Palm Springs, California. Sunnylands has, among other things, its own golf course with, according to the owner, “only nine holes, but the course is laid out in such a way that a total of twenty-seven holes can be played.” There are eight golf carts with blue and white hoods, thirteen man-made lakes and a swimming pool that cascades down on various levels, like a natural stream, and a giant beaucarnia tree—the largest tropical tree that grows—imported from Mexico via Los Angeles. Sunnylands requires a staff of forty-five to run it, and to make sure that his golf course would always have water, Walter Annenberg bought the local water company. The place has guesthouses, equipment houses, and a main house with a fountain copied from the fountain at the Museum of Natural History in Mexico City. The entrance to the house is a room with a high vaulted ceiling through which sunlight pours down into a reflecting pool. Beside the pool, Rodin’s Eve is placed. All the rooms of the house are placed so they view the beaucarnia tree. There is a sculpture garden, a cactus garden, two hothouses—one just for orchids—and Lee Annenberg’s private garden, just off her bedroom suite, is a simple affair: a circle of white chrysanthemums enclosed in a square of Japanese pebbles set in grout, the whole enclosed in a holly hedge. Gardeners make sure that Mrs. Annenberg’s chrysanthemums are always fresh. Visitors to Sunnylands go on picnics with insulated hot and cold picnic baskets, and are driven about in a Mini-Mok, a housewarming present from Frank Sinatra. The list of pleasures available at Sunnylands goes on and on.

The source of all this was a Prussian immigrant named Moses L. Annenberg who came to Chicago at the age of seven, and whose first paying job was as a messenger for Western Union. Moe Annenberg also sold newspapers on the street, swept out livery stables and, before he was eighteen, worked as a bartender in a saloon on Chicago’s tough South Side. In 1900, a brash, rich young man named William Randolph Hearst came to Chicago. Moe Annenberg’s older brother, Max, went to work for Hearst and his new paper, the American, and Max hired Moe. These were the days of the great Midwest newspaper circulation wars, and presently Moe Annenberg was proving himself to be a genius at promoting circulation. Mr. Hearst, seeing this, put Moe Annenberg in charge of his operations in Milwaukee.

Though Moe Annenberg certainly possessed a flair for selling newspaper subscriptions, Walter Annenberg likes to recall that his father’s “first important money” was made as a result of an idea suggested by Walter’s mother. Looking around for a new circulation gimmick, Moe Annenberg asked his wife, “What is the one thing you’re always running out of?” Oddly enough, her answer was teaspoons. Thus the “State Teaspoon” promotion was launched whereby a housewife, for coupons clipped from six daily papers and one Sunday—plus twenty-five cents—received a sterling silver teaspoon embossed with the seal of one of the forty-eight states. Naturally, every woman wanted a full set. Under an arrangement with the International Silver Company, Annenberg sold millions of spoons, and millions of copies of the Milwaukee News. Walter Annenberg remembers sitting with his seven sisters on weekends, wrapping spoons. It is curious that a fortune begun in teaspoons should wind up in a flurry over finger bowls. From then on, Moe Annenberg was into taxicab companies, electric automobiles, restaurants, bowling alleys, grocery stores—into the Racing Form, which he bought for four hundred thousand dollars cash wrapped in old newspaper, into the Philadelphia Inquirer, then the Morning Telegraph, and on into the foundation of what today is the massive Triangle Publications, Inc., which owns radio and television stations and publishes, among other things, Seventeen magazine and the fantastically successful TV Guide—all still completely family-owned.

By the 1920s it was time for the Annenbergs to buy the George M. Cohan estate on Long Island for a million dollars, a place in the Poconos, a villa in Miami next door to the Firestones, and a ranch in Wyoming that covered eighteen miles, with a fabulous trout stream and a house that had curtains made of yellow calfskin embroidered with turquoise beadwork, handmade by the Indians. Two Annenberg family sales made news within weeks of each other—Walter’s sale of his Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News for $55,000,000, and his sister Harriet Ames’s sale of one of her big diamonds that she had grown tired of, for an undisclosed price. The gem, which weighs 69.42 carats, went on display at Cartier’s, where it drew record crowds and was sold to Richard Burton for his wife for $1,050,000. At the time, it was rumored that “the Annenbergs must be going broke.” Nothing could be further from the fact.

At the same time, the cost of all this wealth has been great in terms of human suffering. As occasionally happens in great dynastic families—one thinks of the Kennedys, or the Greek House of Atreus—it is as though the Fates demanded that great men be somehow punished for their greatness. The most shattering blow of all, of course, was Moe Annenberg’s indictment, in 1939, for income tax evasion, and his subsequent prison sentence. When released, in June 1942, he was a broken man and died a few months later. Few children loved their father more than Annenberg’s son and seven daughters. “We worshipped him,” Aye Annenberg Simon says. (She was her father’s “A Number One Girl,” he used to say, which earned her her nickname.) “We thought him all-powerful. During electric storms, when there’d be a flash of lightning, he’d say, ‘Now I’ll push the thunder button,’ and of course the thunder would come. We thought he was God.” The Annenbergs continue to insist that their father’s tragedy was the result of no wrongdoing. There may have been discrepancies in his accounts, they say, but after all he was by then the head of over ninety corporations; for tax advice, he relied on a battery of lawyers and accountants, some of whom may have been unreliable. Certainly, his children say, he did not prepare his own income tax returns, nor did he set about deliberately to cheat the government. Moe Annenberg had entered the New Deal era as a Roosevelt supporter, but when Roosevelt attempted his Supreme Court—packing plan, Annenberg withdrew his support and attacked Roosevelt in a series of editorials. Roosevelt accused Annenberg of being a “traitor,” but Annenberg persisted with the editorials. The word went out from Washington to “get Annenberg”; then came the tax indictment. Their father, his children believe, was simply the victim of a particular political era, just as Eugene Debs, the Rosenbergs, Alger Hiss, and Dr. Spock have been the scapegoats of theirs. What happened to their father in 1939, their lawyers have told them, could not happen in 1972.

The pattern of tragedy has continued. Walter Annenberg’s only son, considered brilliant, was a suicide, and Annenberg was so staggered by this blow that news of it was withheld for a week, as though he could not bring himself to believe that it had happened. One of his nieces was also a suicide, and another died tragically of cancer. A nephew, Robert Friede, was involved in a drug-manslaughter scandal several years ago for which he served a prison sentence. All Walter Annenberg’s sisters except one—a widow—have had divorces, and Walter’s own first marriage was a particularly unhappy one. The Fates at times must have seemed relentless.

And yet it is absolutely certain that His Excellency Walter H. Annenberg, United States Ambassador to the Court of St. James’s, would not be the man he is or where he is if it had not been for the grim day in 1939 when he heard the verdict passed down against his father. Walter was thirty-one at the time. Up to then, he had been a shy, withdrawn young man living in his father’s shadow. Suddenly he was head of the house, responsible for his mother and the seven sisters, older and younger. Ever since, he has worked diligently to enrich his family—as he certainly has done, to the point where, barring the most unusual circumstances, Annenberg heirs will be wealthy for many generations to come—and has worked even more doggedly to vindicate his father, to clear and elevate his father’s name. Engraved in gold on a wooden plaque, prominently displayed in all his offices wherever he goes, are the words:

CAUSE MY WORKS ON EARTH TO REFLECT

HONOR ON MY FATHER’S MEMORY

This has been the single most important, most consuming, mission in Walter Annenberg’s life. He may not always have succeeded, but he cannot be faulted for not trying. Sitting behind his big desk at the Embassy in London, he said, “Tragedy will either destroy you or inspire you, and I continue to have many inspirations to reflect credit on my father. In fact, I feel sorry for people who do not have great incentives in their lives. Great incentives can be sobering and inspiring.” Walter Annenberg is a man who lives by mottoes; in fact, he has his favorite quotations typed up and printed on mimeographed sheets so he can carry them with him and refer to them for inspiration. Some of the ones he finds most comforting and reassuring are: “Today, well lived, makes every yesterday a dream of happiness and every tomorrow a vision of hope”—William Osler; “Our main business is not to do what lies dimly at a distance, but to do what lies clearly at hand”—Thomas Carlyle; “The high places occupied by those who are genuinely repentant cannot be reached even by the righteous”—the Talmud. His favorite is this, from an unknown source: “There is no misfortune but to bear it nobly is good fortune.”

Annenberg says, “For every advantage a citizen has, he has a corresponding responsibility. Having had more than my share of personal success, I have felt my obligation particularly strongly. All my life I have endeavored to be a constructive citizen.” He has endeavored to be constructive through philanthropy, and heads three charitable foundations, one named in his father’s memory. He has given the Annenberg School of Communications to the University of Pennsylvania, and the Annenberg Library and Masters’ House to the Peddie School, the latter given in honor of the masters who taught him as a student there. He has also toiled for the Philadelphia Art Museum and, in the process, has assembled an imposing collection of nineteenth- and twentieth-century paintings which he has been generous in lending to galleries and museums. He has striven to have the Annenberg name linked with philanthropy and public service, and clearly he feels that his ambassadorial post is just another way he can “reflect honor” on his father’s memory.

But is he the right man for the job? Or is he, as his harshest critics say, actually hurting U.S.-British relations with his ineptitude and lack of experience? Of course, much of the criticism of the Annenberg appointment started in America and preceded his arrival in London. It was pointed out that he knew little of Britain, except as an occasional tourist, and that his biggest newspaper, the Inquirer—since sold—didn’t even employ a foreign correspondent. Much was made of the fact that two Annenberg publications were racing papers, “a service that supplied bookies with racing results.” This, of course, is rather like calling the Wall Street Journal “a service for illegal manipulators and shady speculators,” because Annenberg’s Morning Telegraph, after all, is the official newspaper of the Thoroughbred Racing Association and of the National Association of State Racing Commissioners. It lists among its subscribers none other than Queen Elizabeth II, who knows more about horses than about ambassadors’ addresses. Needless to say, at the time of the appointment, Moe Annenberg’s tax troubles were taken out and dusted off.

Leading the criticism in America was the New York Times—now known in the Annenberg family as “The goddamned New York Times.” In a sharply worded editorial, the Times took President Nixon to task for “returning now to the unhappy practice of parcelling out key embassies to major campaign contributors” and said that Kennedy and Johnson had “scrapped” this tradition. Today, Walter Annenberg carries the Times editorial, slightly dogeared, in his date-book, and appears to have it committed to memory—the way actresses sometimes memorize bad notices. He takes it out, brandishes it, pounds the desk as his gorge—and voice—rises. “I made no political contributions!” he cries. “I have not one nickel. This is an editorial based on falsity. This is a textbook example of yellow journalism!” He also claims that at least two ambassadorial appointments of which he has personal knowledge—Matt McCloskey as envoy to Ireland, under Kennedy, and Frederick Mann, to Barbados, under Johnson—were both the result of money contributions. He knows this, Ambassador Annenberg says, because both President Kennedy and President Johnson telephoned him and told him so at the time.

On this rather important point—whether or not Walter Annenberg gave money to the Nixon campaign—it is hard to get a definite answer. Back in New York, John B. Oakes, the Times’s editorial director, expressed astonishment that Annenberg had accused the Times of lying, and said, “Why, it’s been part of my general knowledge that Annenberg has been a big contributor,” which seems a somewhat flimsy basis for an editorial claiming this to be a fact. Since the appointment, the Times has continued to needle Annenberg, once commenting that a room in the Embassy where a reception was being held “looked like a place where people gulp down a quick, cheap lunch.” With the British press continuing to be hostile or mocking or both, there were signs, by the fall of 1969, that the Annenbergs were visibly wearying of the attack and that Annenberg might indeed offer his resignation by mid-1970. Later, though, the British press became kinder, led by the Evening Standard, which commented that “Mr. Annenberg has impressed independent observers by his sincerity and determination. Perhaps the critics will relent a little when they get to know him better.” Even the New York Times has adopted a gentler tone.

Socially, the Annenbergs still have problems. In this, it is a question of the Annenberg style. No two men could be more unlike than Walter Annenberg and his predecessor, David Bruce. Bruce was elegant, urbane, soft-spoken, polished—a trained diplomat of many years’ experience. Annenberg is bluff, tough, forthright and—in some of his overexplanations—incautious. To the mannered world of social London he seems—well, coarse. The Annenbergs have never been exactly shy about admitting how rich they are and, to social London, talking about one’s money is something “not done.” When asked how much the Annenberg collection of paintings was worth, the Ambassador replied, “Priceless.” When asked if it was true that he was personally spending over four hundred thousand pounds of his own money on “refurbishing and rehabilitation” of the residence in Regent’s Park, he exclaimed, “It’ll be closer to five hundred thousand pounds!” Social London tittered, and Queen magazine noted that the Annenbergs’ decorator was William Haines, “a former star of silent screen, who appeared in ‘The Fast Life,’ ‘Tell It to the Marines,’ and ‘Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford,’” adding that the new ambassador possessed an honorary doctorate of laws degree from Dropsie College. In yet another interview, the Ambassador was asked whether he could be photographed on an exercise slab where he works out for ten minutes each morning. “I do that without any clothes on!” he roared. “May I tell you that as a representative of the President, I’ve got to consider the dignity of my office.” Tee-hee, went smart London.

The ambassadorship to the Court of St. James’s has become a social post, and was certainly used that way by the very social David Bruces. The job is not one that is considered “politically sensitive.” Though it is the most prestigious post an American can occupy, it is also—from the standpoint of politics and American diplomatic goals—one of the least important. What does the American ambassador in London need to do besides go to parties? There are signs, however, that Walter Annenberg may see his role as a somewhat broader one than the purely social one it can easily be. “Our overriding goal,” he said, “should be to contribute to the Anglo-American relationship and to show in tangible and visible ways to the British people the depth of our common interest.” He intends, he claims, to extend himself deeper into British life than that part of it populated by dukes and duchesses. He has instituted a series of lunches with both business and labor leaders, and recently enjoyed a miners’ gala in Durham. He is also eager to prove himself a working ambassador. In a recent 77-day work period, he made 45 official calls, received 189 callers, went to 35 lunches, 24 receptions, 53 dinners and 16 excursions, including the miners’ gala.

David Bruce is a very English American, and Walter Annenberg is a very American American. He champions traditional American values—motherhood, virtue, President Eisenhower. His house in California has an “Eisenhower room,” with nothing in it but photos and mementoes of his late friend and golfing companion. He also has a “Mother’s room,” in memory of his mother, with a pale pink carpet—his mother’s favorite color. Her portrait, in soft pastels, dominates his private study now in the house in Regent’s Park. He calls Mrs. Annenberg “Mother.” He dislikes swearing, hippies, student activists, Democrats, and he and his wife take turns at writing a long and chatty weekly newsletter, headed “Dear Family,” that goes out to all his sisters and other relatives.

Jocelyn Stevens, publisher of the Evening Standard, is not only an influential Briton, but also a very dashing young man about London, with all proper social credentials. “It’s really gotten to be very bad,” he says. “You’re invited to a party, and your hostess will say, ‘I’m afraid we’re having the Annenbergs.’ On the other hand, do the bitches matter? Do they count, in the long run? I tend to suppose that, once their house is finished and they throw a few good parties, people will come around.”

It’s true. All the costly refurbishing had held the Annenbergs back, because they had been unable to entertain. Now that William Haines’s ministrations are complete and the great paintings are hung on the walls, the doors at Regent’s Park are open, music is playing and wine is flowing. Certainly in Philadelphia no one ever complained about an Annenberg party, where, needless to say, few expenses were ever spared.

And Walter Annenberg is a tough, determined man, and one gets the impression that he will not let social London get him down. Still, at times, he displays a certain nervousness, small signs that he is under a strain. Not long ago, speeding across London in his long limousine, on his way to pay an official call upon the Rumanian ambassador, his car drew up to the curb. The chauffeur hopped out and opened the door for Ambassador Annenberg. Suddenly, in an anxious voice, he asked, “Are you sure this is the place?”

“Yes, sir, this is it. Number one Belgrave Square.”

The Ambassador seemed unconvinced. “Are you positive?” he asked, touching his chauffeur’s sleeve. “Are you sure I’m where I’m supposed to be?”