19 October – 3 November 2011

Shirley: Oh bugger! It’s 4.15 am. The bloody alarm didn’t go off. The cab will be here in 15 minutes. Now the mad rush is on.

•

We were bitten by the overland travel bug back in 2003 when we took a year off work, the middle-aged version of the gap year, and rode our BMW 1150 motorcycle from London home to Australia through Europe, the Middle East and Asia. It was a dream fulfilled and that should have been the end of it, but there’s so much more of the world to ride.

This morning we’re flying to Chile. Our motorcycle left a couple of months ago by sea. We’ll meet it in Chile and begin a massive ride from the bottom of the world to the top. Brian has hankered to ride the world from south to north ever since we got home from Europe in 2004. This is our big chance to fulfil another dream. From Santiago we’ll head south to the southernmost point of South America. We’ll have to abandon the bike when we get on a ship to Antarctica that should take us to the Antarctic Circle. Then we’ll ride north to the Arctic Circle and beyond to Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, the northern most point of the Americas. Circle to Circle — that’s the plan.

For the past few weeks we’ve been on a merry-go-round of farewell dinners and drinks. Last night we reflected on how different our lives will be now we’ve retired: Brian after 36 years as a policeman and I’ve virtually closed down my 20-year-old media business. We’re about to embark on the trip of a lifetime, hitting the road again, this time on a BMW R1200 GS Adventure. (The 1150 GS was written off when Brian and a 4WD had an altercation on a dirt track in the Victorian high country. The bike came off second best. It was a write-off. Luckily, Brian was okay)

We’re not sure when we’ll come home, but probably sometime in early 2013. After Alaska we’ll see where the road takes us. This is all part of our desire to live a life with few regrets.

Brian: Packing is always a big deal on a motorcycle trip and it’s even trickier for us because we haven’t seen the bike for a couple of months. We have to guess how much room we have for our clothes, accessories and the bike spares. This never ends well.

Sleeping in when we have a plane to catch isn’t a good start. We finish the final packing in 15 minutes, squeezing in Shirl’s bathroom/make-up bag. It’s huge. Has she lost her touch? I think she’ll have to pack better once we get the bike. I don’t seem to remember this being such a big issue last time, or maybe I’ve pushed that out of my mind. Hair seems to be the main thing — a product for this, a product for that. Spare me, it’s not that important. Then again, I’m bald.

Our luggage consists of two huge bags — one full of clothes and bits and pieces, the other full of bike riding gear, boots, jackets and pants; our hand luggage is in the tank bag and a soft bag that will mount on the top box; Shirl’s big handbag with books and essentials for the flight to Chile; and two helmets. We struggle into the airport and, with some relief, check our luggage all the way through to Santiago.

•

Things are going very well until I bite into a hard mint offered by a friendly airline staffer. I promptly break off part of a tooth. Great! We’re not even on the plane. This isn’t a good start. It’s not down to the nerve but I’m so pissed off.

•

Several hours into the flight the captain announces our arrival over the coast of South America just as the morning sun is on the Andes and the rugged beauty of snow-capped mountains, stunning valleys and inaccessible, barren terrain is breathtaking. This is the land we’ll be exploring.

We have a couple of months to get from Santiago to Ushuaia in southern Argentina for the trip to Antarctica. It seems like a long time but there’s so much we want to see on the way. There are the amazing passes through the Andes, the lakes, the glaciers and the national parks. We could take a cruise through the Chilean fjords but that would be cheating. It’s a motorcycle trip and we’ll ride the roads, no matter how challenging they turn out to be. If we can ride through the Middle East and Asia, we can ride through the Americas — we hope. We’ve done as much preparation as we can. Now we need to get moving.

Shirley: We don’t expect the bike to arrive for a week so we’ve booked a holiday at the beach, a couple of hours from Santiago. We need to recharge the batteries after the last few hectic months winding up our working lives. We need to be at the top of our game for this ride.

Our Spanish isn’t too good so we get help to ring the freight company and check on the arrival of the bike. It’s not good news. It should be here on November 3. Bugger! We’ll just enjoy our week at the beach and then sort out where to go for the next few days.

Every day we spend waiting for the bike takes a day off the time we’ve got to get to Ushuaia. It might mean missing out on some things, but we’ll worry about that when we’re on the road. There’s no point in getting stressed because there’s nothing we can do about it. We’re now officially at a loose end. It’s a very strange feeling to be on a motorcycle trip without a motorcycle.

We fill in time travelling around the Chilean coast in a hire car. The locals make the most of their beaches, swimming, sunbaking and playing soccer in the sand. We love the wide beaches, but take note of their tsunami escape routes.

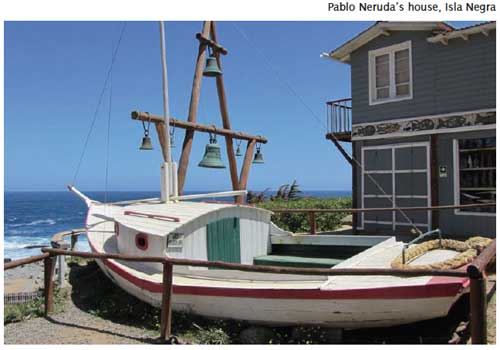

South of Valparaiso is Isla Negra, the house of Chile’s Nobel Laureate and favourite poet, Pablo Neruda. He was a prolific collector and his house on the Pacific Ocean is now a museum. His eclectic collection includes bowsprits hanging from the ceiling, ships in bottles, insects in glass cases, ornaments, masks and his personal pipe collection. We have to do a tour to see inside the house and the only one on offer is in Spanish. I’m surprised at how much I understand and horrified at how much I don’t.

We head to Valparaiso to check out where the bike will arrive. The centre of town is old, rundown and, in some ways, intimidating. Everyone has warned us to be careful of our belongings here. It’s a port town, they say, with trouble around every corner.

I spot the Melbourne Café on the main square, Plaza Sotomayor, and we find a little piece of home. Daniel, Daphne and Jorge have all spent time in Melbourne and share our love of the city. They have a warning for us about the bureaucracy we will have to get through to get the bike and offer to help where they can.

Brian: Valparaiso has a seedy feel to it but it also has a funky side. Shirl worries too much!

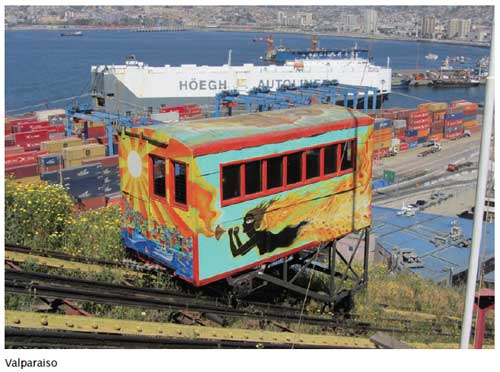

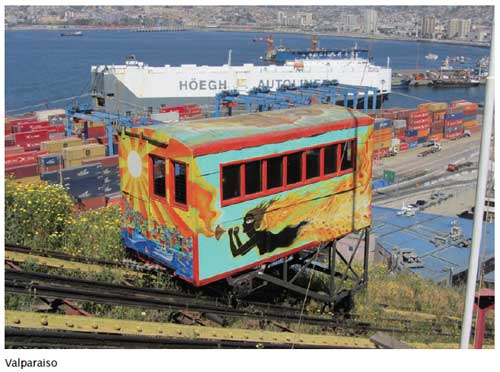

We take the ascensor trolley car to the hill high above the town. We look down on the wharf at the thousands of containers and the ships waiting to come into port. Somewhere out there is our motorcycle, we hope.

I really need to get my tooth fixed. It’s more annoying than painful. My tongue is constantly catching on the rough edge and I’m always aware of it. So, armed with a little Spanish and the phrase book, we head out to find the local dentist. The tourist information office directs us to the 18th September building (named to honour an important date in the Chilean independence process) but this seems to be a place to pay medical bills. The security guard draws a little map directing us around the corner to the dental clinic.

Now the problem is making ourselves understood. The receptionist doesn’t speak any English but she gets the message. After 10 minutes the young female dentist comes out, puts her hand on my shoulder and asks, ’Are you in pain?’ She is lovely. A quick and painless jab, lots of drilling to take out an old filling and she and her assistant reconstruct half a tooth in no time flat. The dental work complete, she warns me to have it checked out after the trip and I will probably need to have an x-ray to make sure all is okay. I hope it will last until we get home, at least a year from now. As I get up out of the chair she wishes me well and gives me a kiss. You don’t get service like that back home. Certainly our dentist, Stuart Cran, is a good looking man but I don’t want him to kiss me!

•

We enjoy the beaches, the towns and the food in Chile, but our minds are elsewhere. We just want to get the bike and get on the road. The trip has been two years in the planning and this waiting is killing us. After a week the shipping agent sends the paperwork for the bike to our hotel. We’re now one step closer to starting our journey. The upside to this time on our hands is the discovery of the Chileans’ drink of choice — the pisco sour. One is delicious; two are calming; three are too many.

It’s prohibitively expensive to comprehensively insure a motorcycle when you’re on a trip like this, but everyone we talk to says it’s compulsory to have third party insurance to cover the other people if we’re unfortunate enough to have a crash. Jorge and Daniel at the Melbourne Café have made a few calls and they can’t find anyone who’ll sell it to us because we’re on a foreign registered bike. After several frustrating hours with a local insurance salesman in the beachside town of Vina del Mar, a phrase book and a Chilean biker friend on the other end of the phone in Santiago acting as an interpreter, we still can’t buy the insurance. It’s like a scene from Catch 22. We decide to just take the risk.

•

Shirley: We’ve been in Chile for two weeks and at last we get the call we’ve been waiting for. Our freight agent, Anna Maria at ILS, rings to let us know the bike’s here. It arrived on board the Monte Pascoal, which hit Chilean shores on the 31st and has just been offloaded. The good news is we can arrange to collect it after 3.30 pm this afternoon. The bad news is the freight yard closes at 5.30 pm.

We arrange for a car and driver to take us from the hotel in Vina del Mar to Valparaiso. The eternal optimists, we put on our bike gear and take the helmets — just in case the customs process is easy.

Brian: Armed with the paperwork from the freight company and our Carnet de Passage (a document issued by the Automobile Association of Australia that proves the motorcycle is owned and registered in Australia and will be returning there) we head out with our driver, Sergio.

At the port at Valparaiso I walk confidently into an office that looks official. I know I’ve made a blue the second I walk in. Instead of pen pushers and a flurry of freight agents I find men in uniform, armed with machineguns. This is more than a little startling. I’ve stumbled into a Chilean naval base office. I ask them in Spanish even worse than Shirl’s where aduana (customs) is but after plenty of smiles they point towards the other side of the plaza.

Now we’re in the right office, a very pleasant man takes our papers and wanders into the back offices. Freight agents armed with paperwork come and go but the man with ours hasn’t reappeared. Time ticks by and Shirl goes out twice to tell Sergio to wait a little longer. With the phrase book and a bit of charades she makes him understand. He seems happy enough.

When our agent finally reappears it seems that he’s been making a few calls to help us out. It’s obvious we are foreign and perhaps a little out of our depth. He indicates the carnet is no use here and that we need to get a document signed by the importing company. He’s written down the address and the name of the person we need to see. He couldn’t be more helpful.

Even with our bad Spanish Sergio understands what’s going on. He drives us a few blocks to 1215 Bianca Calle. We head up to the 11th floor and wander down a dark corridor to an office where the man is expecting us. In two minutes we have the document we need, verification that we’ve paid the shipping company’s bill. (Actually, we haven’t, but Anna Maria must trust us.)

We hope this is the end of the paperwork, but it’s not. The next stage is written on the note from the customs officer. Before they’ll issue the permit to bring the bike into Chile we need proof that the bike is actually here. This means getting a piece of paper from the freight company. The only difficulty is that the freight yard is 15 kilometres away from the port.

Shirley: Back in Australia we were told we’d require a Carnet de Passage to temporarily import the bike into Chile. Ah, but no. Instead we need all these pieces of paper signed and stamped. Okay, smile, walk away, swear under your breath and get into it. We have firm rules when we travel — always smile at the man who can stamp your passport at the border, and the one with the AK 47. This is one of those occasions.

Brian: It’s getting too late to pick the bike up but we bite the bullet and ask Sergio to drive us out to the container depot anyway. The more we get done today the quicker the final stages will be tomorrow.

Sergio is proving to be a great asset. He can’t find the depot, but rings them on his mobile and gets directions. Right on 5.30 pm, their knock-off time, we roll into a modern holding yard full of workmen, cranes, semi-trailers and security guards. It’s unnerving and Shirl is getting edgy. We ask for the directore and are directed to a very modern office where Shirl asks the receptionist in her best Spanish, ‘Habla Inglés por favor?’

‘Yes, I do,’ is the instant reply from the lovely Andrea and Shirl just about falls into her arms with relief. Andrea grabs our paperwork, including the hand written notes from the customs guy and shakes her head, ‘Welcome to the world’s biggest bureaucracy. It is crazy! Don’t worry. We’ll sort it.’

Andrea immediately gets on the phone, chasing paperwork and writing out directions. She asks if our driver speaks Spanish. Well, he does. The problem for us is that he doesn’t speak English. So Andrea gives Sergio a briefing about where we have to go tomorrow and what we’ll have to do. Once we have the permit we’ll be able to get the bike — no problems.

Shirley: It’s been a long day and we feel we’ve earned a drink — pisco sours all round. This afternoon we met a taxi driver who probably thought he was lucky to get a 10,000 pesos (about US $20) job from Vina del Mar to Valparaiso. He has driven us around for more than three hours and waited patiently while we tried to work our way through the paper maze that is the Chilean bureaucracy. Despite the fact he doesn’t speak more than a few words of English and our Spanish is rubbish, Sergio is part of Team Rix and will pick us up at 8.30 in the morning.

Brian: Sergio is waiting outside the hotel at 8.30 on the dot. He seems as excited as us and ready for business. He has his instructions from Andrea and takes us straight to the office that will issue the permit. He comes into the office with us, holding his mobile phone and Andrea’s phone number at the ready. He has taken on the team leader role and speaks to the officials on our behalf, to get things going.

The office is very olde worlde with wood panelling and frosted glass windows. There’s a hum of people working and the clack of manual typewriters. There are no computers and printers here. We feel like we’ve walked back in time.

The officials take the paperwork we got yesterday and again completely ignore the carnet. The forms are filled out the old fashioned way — by typewriter. And the man completing the paperwork is typing the old fashioned way — with two fingers. You certainly need to be patient.

The teenager, who seems to be the junior assistant, scurries away with the paperwork to get it photocopied. When he gets back copies are pinned together and put in a tray for filing. After about half an hour of waiting and answering the odd question, we have the all-important Titulo de Admision Temporal de Vehiculos.

We jump into Sergio’s car and head back to the freight yard. Sergio doesn’t want to leave us until he is sure we are able to collect the bike. Once we are with Andrea and wearing the all important high-visibility vests and hard hats he wishes us good luck with our journey and gets in his little taxi. Who needs a freight agent when you have a good-hearted driver like our new best friend, Sergio?

We walk down the yellow brick road, literally, following the yellow paving from the office to the freight warehouse. Huge cranes are picking up shipping containers and shifting them here and there. Andrea insists that we must keep our hard hats on even though she admits they won’t do much good if a container drops!

We’re introduced to the manager of the warehouse and he sends a forklift down to pick up our bike. I can feel the butterflies in my stomach and look at Shirl. She’s tense. We don’t know what condition the bike is in, it’s been at sea for such a long time.

Shirley: So close, but we can’t get our hands on the bike until the onsite customs officials sign the paperwork. And finally we have it. The bike is sitting on its pallet — safe and sound. Unfortunately we can’t put it back together in the shade of the warehouse, and it’s forklifted out to an area in the blazing sun.

Brian: The sooner we put everything back as it should be the sooner we can get out of the searing heat. I decide to do everything I can with the bike still strapped on the crate and then I’ll ride it off — if it starts, of course.

We take our time to make sure we get things back where they should be, with no left over bolts, screws or washers. The racks that hold on the luggage are reattached. The handlebars lifted to the correct level and the screen refitted. I make good use of Shirl’s smaller hands to get behind the windscreen and start the self-locking screws.

I tossed and turned all night thinking about what to do if didn’t start. I decided we could fork it onto the back of a truck and take it somewhere to get a battery, and I remembered seeing a motorcycle shop near the freight yard. But now it’s the moment of reckoning. I connect up the battery, turn on the bike and let it cycle through its start-up procedure. I press the button and after a few coughs and splutters the big red beast fires into life. You bloody beauty!

By now we’ve an audience of truck drivers. I snick into first gear and, with a front tyre with precious little air in it, I ride it off the crate. The back wheel breaks a few bits of wood on the way and I have to pull up as soon as I clear the pallet to avoid running into a shipping container, but we finally have our bike on terra firma.

All the emergency lights are flashing on the dashboard — low fuel and low air in the tyres — so I use our portable compressor to get the tyres up to a rideable level and we head for a petrol station.

Our adventure is about to begin. There are 48,234 kilometres on the clock. There’ll be another 20,000 or 30,000 kilometres on the clock by the time we get to Alaska.