1 – 14 April 2012

Brian: The immigration officer at Panama City airport doesn’t ask when or how we’re leaving the country. There’s no question about a ticket out of the country. All that stress and aggravation in Bogota was for nothing.

Rather than the third degree, they give us a free emergency medical treatment card covering our first 30 days in Panama. It’s a nice touch, giving us a number where we can get medical help and advice in English.

•

We’ve battled plenty of borders with our very average Spanish. When Rae, our taxi driver who speaks English, offers to help us through the customs process for a few extra dollars we readily agree. It turns out to be money well spent.

The airport freight area is a jumble of small buildings and warehouses with no signs. Without Rae’s help it would have taken ages to find the customs and freight offices, let alone get the paperwork done. The bike is brought out and I try to start it. It won’t kick over. I can’t believe the battery is flat after just a couple of days. There’s no option but to try and push start it. I get a run up on the driveway and the bloody thing overbalances. Next thing I know it’s lying on its side and Shirl is running towards me, panicking.

The bike is fine and I’m fine, but a little mystified. I didn’t need to disconnect the battery for the flight. Then it dawns on me. I put the kill switch on when I lodged it at Bogota. It’s something I rarely do. How embarrassing. A flick of the switch and it starts first time and we’re on our way to the petrol station. Just as we leave the airport the sky turns black and down comes the rain — a typical tropical downpour. No point in stopping to put the wets on as we’re soaked to the skin in a couple of minutes. It’s not so bad, we dry off pretty quickly riding in the warm air.

On the way back to the hotel the bike begins to run rough, like it’s about to stall. I can’t work out what’s wrong with it. I stop at a Honda dealer who can’t help, but he tells us where to find the local BMW dealer. They can’t help now but will be able to in the morning. I nurse the bike back to the hotel, convinced we have a major problem that’s going to cost a fortune to repair.

•

Shirl’s keen to organise a refund on the airlines tickets we had to buy to get out of Columbia. The airline is very helpful, up to a point. They’ll rush the refund through for us in three months. I can’t imagine how long it’d take if they didn’t rush it through!

Shirley: It’s a black day. I’d planned to talk to our friends Ian, Sylvia and Phil this morning. They’re meeting us in Texas in a month and we want to make some final plans. I can’t wait to see them.

Instead of a happy conversation it’s a sad one. Phil gives us the devastating news that her wonderful dog, Gypsy had to be put down this morning. Gypsy is like one of our family — she spends so much time with us when Phil is working. We both cry while we talk to Ian and Phil. This is the worst news.

I cry on the bike on the way to BMW. I cry at BMW. I cry while we have breakfast — bloody hell, I feel so miserable and such a long way from home. I know Brian feels it too, but he does ask that I stop crying in public — people will think he’s been beating me. I’ll try.

The good news is that the bike is running badly because one of the spark plugs has worked loose. Instead of a massive bill it cost us just $13.91. This is probably the cheapest bill we’ll ever get from BMW.

Another good turn of events is the insurance for the bike. A local dealer can organise it for $15 for one week.

We both need a fillip after the sad news about Gypsy so we treat ourselves to a sushi dinner with a good bottle of wine. It’s way over budget, but what the hell, it’s scrumptious. We do feel a little better when we head off to bed.

•

Panama City is fascinating with old and new side by side. You can see the US influence from their years meddling in the country’s politics and the construction of the Panama Canal in the steel and glass highrise developments. The old city, Casco Viejo, has its own charm with its dilapidated and boarded up buildings and historic mansions being restored to their former glory. Over decades the area became a slum that’s now being gentrified. There’re still plenty of incredibly rundown places that obviously offer cheap housing. What will happen to those families when all the buildings are renovated?

We’re both taken with the old churches, particularly the Church of San Jose with its golden altar. In the 17th century, to protect the altar from the pirate Henry Morgan, the priest painted it black. He told Morgan it was a fake because other pirates had already stolen the golden one. Legend has it the priest even wangled money out of Morgan to replace it. Smart man!

The biggest tourist attraction is the Panama Canal. They say 14,000 ships pass through the Miraflores Locks each year, but we don’t see one. Pity, it must be quite a sight and an incredibly tight fit. Our timing isn’t good here. We also miss out on a boat trip on the canal because they only run on Saturdays and we have to be on the road by then. Texas is calling.

•

Over the years we’ve found the Horizons Unlimited website invaluable for information on borders, road conditions and the like. We’ve also met quite a few interesting travellers through this forum. One of them is Steve Barnett, a US expat now living in Panama City, who in his middle age enjoys the laidback attitude of Central America over the hurly burly of the US.

Heading out to meet him we overhear a young girl asking a man checking into our hotel if he would like some company in his room. Steve tells us that the hotel is renowned for the number of prostitutes working out of it. The girls are brazen and the hotel staff seem to turn a blind eye, and may even encourage it.

Steve looks more like a businessman than a biker. He’s travelled a lot through Central America and has some good advice about the roads. He’s on his way to Alaska in a few months so we may well meet him on the road.

Brian: It’s Easter Thursday and we overnight in David City on our way to Costa Rica. Panama is a very religious country and they don’t sell alcohol over Easter, something we’re not used to. Our hostel clearly caters for thirsty international visitors and has a fridge stocked with cold beers and soft drinks for a $1 a bottle. After a hot, muggy day on the road from Panama City a cold beer hits the spot.

Across the road is a small restaurant, tucked at the back of a family home. They serve the tastiest fish dish with banana fritters for dessert. Throw in a couple of cokes and it sets us back just $7.20 for two.

A cab arrives at the hostel and a young girl hobbles in on crutches followed by her mum, carrying her bags. She broke her hip when she fell off a roof. It seems she’d been partying with some locals and they drugged her. She’s lost several days. We feel for her mum, who’s flown in from England and is trying to convince her to come home with her. The girl is determined not to go home, but wants to continue backpacking — crutches and all.

It’s a scary story but I’m a little sceptical, particularly when she tells me she fell three storeys onto a roadway. But then, maybe I’m still naturally suspicious after all those years as a copper. I ask her a few questions and she becomes very evasive. She’s keen to get talking to others and leaves us talking to her mum.

•

We’re heading to San Jose in Costa Rica and all I can hear in my helmet headphones is Shirl singing Do you know the way to San Jose? Her singing will definitely drive me crazy before we get to San Jose. She doesn’t know all the words, just the opening verse and is singing it over and over and over again. The intercom system is voice activated and I can’t turn it off. It’s going to be a long day.

The border crossing is slow. There are a couple of buses ahead of us and only one man checking the passports. We have to buy a sticker for our passports for $1 each and no-one can explain why. The customs office is closed and it takes a little while to find someone to stamp the bike’s papers so we can leave Panama. We haven’t even begun to try and get into Costa Rica yet.

On the other side of no man’s land there are signs requesting yellow fever certificates and a ticket out of the country. Shirl has a copy of the now cancelled flights so that might do but in the end it’s not needed. The officials don’t ask for any paperwork other than our passports. In a matter of minutes we have our visas.

We’re glad we’ve got our yellow fever certificates, to prove we’ve been given the vaccination. We’ve heard horror stories of travellers being forced to get the vaccination when they arrive at the border. The story goes they use the same needle and keep the serum in a jar under the counter. It might be apocryphal, but we don’t want to test it!

For the customs approval we need the SOAT insurance and photocopies of our visa and the insurance papers. Opposite the customs office is a small building where a man is selling the insurance and the photo copies. He knows exactly what we need and it doesn’t take long to get it sorted. Despite being relatively straightforward this border crossing has taken nearly three hours — our longest to date.

Because we’re time poor we’re just riding through Costa Rica with an overnighter in San Jose. We’ve checked out the guidebooks and the maps and have worked out a tight schedule to get us to the US in a month that allows us to see some of the sights of Central America. The best thing about getting to our hotel is Shirl stops singing.

It’s Good Friday and our hotel doesn’t sell alcohol but we can buy meat. This is very different to home where Good Friday is traditionally a meat free day.

•

Shirl’s mood has been up and down a bit lately. The sad news from home about Gypsy has been a bit tough for her. As we ride to the border I resolve to take the load off her today, as much as I can.

A tout offers to help us through the Costa Rican border but I decline. Leaving the country is usually pretty straightforward. Finding the customs office is a bit tricky, even with the help of local police. Walking backwards and forwards in more than 35°C heat is debilitating. Shirl waits in the shade, lost in her own world.

I pass some poor bugger with his VW Kombi van parked in the no man’s land on the edge of the border with a ‘for sale’ sign. It seems like an odd place to try and sell a car.

A Canadian ex-pat whose wife is running a café outside the immigration office tells me the Nicaraguan border formalities can be tricky, so I do take up the offer of help from Charlie, the well-dressed tout who says he’s the government representative there to help with English speaking tourists. He exudes confidence and in impeccable English explains his payment is ‘just what you want to tip me’.

There are plenty of things to do and pay for to get through this border: first, fill out the customs cards; pay $3 to have the bike fumigated with some lethal spray to kill any rogue mosquitoes that may have the temerity to cross the border with us; pay $1 for a loose stamp to go into each passport; pay $12 for each visa; another $12 for the compulsory insurance; $5 to the tourism authority; and, finally, a free stamp from the police.

After a customs officer gives the bike a cursory inspection, a woman in another office types something into the computer; another police officer stamps another piece of paper. It’s all stapled together and we’re free to go. Thanks Charlie. You earned your $10 tip.

Shirley: We skirt the western side of Lago de Nicaragua with its smoking volcano. Every five kilometres there are police roadblocks but they just wave us through. As we move towards Granada the roads become choked with utilities overloaded with people heading home after a day at the lake. No safety rules here. I lose count at 15 in one.

We may be in a rush but Granada and Leon in Nicaragua are on our ‘not to be missed’ list. Granada is a colonial city that’s been restored to its previous grandeur. The main square is ringed by wonderful buildings, and huge mango trees grow in the main plaza, making it a top spot to beat the midday heat. Small kiosks sell cold drinks while kids dash about and artisans sell pottery and jewellery. It’s alive with people, horses and buggies, food vendors and church goers making their way to the grand cathedral. Inside the congregation is singing a hymn — When the Saints Go Marching In. It sounds fantastic in Spanish.

Our hotel, the Blue Dolphin, is a little way out of town, away from the crowds. It’s run by 77-year-old US ex-pat Carl and his Nicaraguan wife, Carolina, and her father. We join Carl and his ex-Marine buddy Larry for a poolside drink. The conversation is interesting to say the least. Larry tells us all about President Obama being a Muslim who wasn’t born in the US. His solution to the world’s problems is bombing Iran off the face of the earth. It’s madness. I have to leave the table, just in case I say something we’ll all regret.

There are warnings in the guidebooks about Granada. They say it’s a dangerous town where street robberies are common. Exploring the side streets around the main plaza we bump into Carl, sipping coffee with some friends outside a small gallery come café. We stop to chat, and after introductions Carl advises that when we walk around Brian should walk behind me so if a bag snatcher tries anything he can react. It seems like good advice.

•

The wear and tear of daily use is starting to show on our gear. One of our pannier bags has split on a couple of seams and the zipper has broken in the tank bank. Both are now being held together with gaffer tape. (Note to all travellers: never leave home without gaffer tape and cable ties, the modern day equivalent of eight-gauge fencing wire. They can resolve many problems on the road).

Carolina takes us to her dressmaker, but he can’t fix them. He suggests the boot repairer. Set up on the side of the road in the heart of the busy market, the boot repair shop has a sturdy sewing machine and one of the men is doing some fine hand stitching. For the equivalent of less than $20 we get both fixed and it only takes an hour. Try that at home.

•

Las Isletas, the 350 islands that dot Lago de Nicaragua are homes to wealthy businessmen and local fishermen who eke out a living with their nets. Over the 18th century fort on Isla San Pablo we see the distinctive black and red flag of the Sandinista for the first time and it won’t be the last. Named after the freedom fighter and rebel leader Augusto Sandino, the Sandinistas run the government in Nicaragua again. Augusto is a hero here. The president, Daniel Ortega, might not be popular overseas but the locals seem to love him.

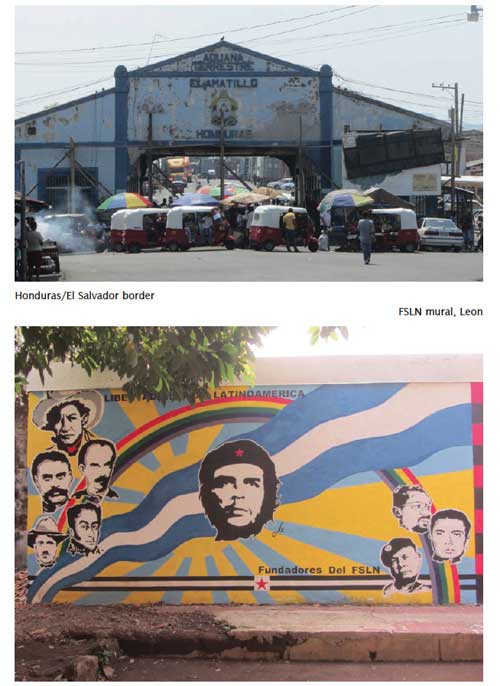

Brian: In Leon, Nicaragua’s second largest city, there’s a fascinating museum commemorating the heroes of the war against the Contras. It’s based in the FSLN (Sandinista National Liberation Front) headquarters from the 1970s. The colonial building would have once been a showcase of wealth and opulence. Today, you can still see the bullet holes in the stonework exterior that’s emblazoned with portraits of revolutionary leaders including Ché and Fidel Castro.

You can’t tour the museum without a guide. Ours displays a passion for the stories of revolution that only someone who has lived through it can. He takes great pride is showing us a photo of himself as a 14-year-old boy before he was wounded in a running gun battle in the street outside this building. He shows us the bullet scars on his back, so proud that he nearly died for his country. The adage ‘one man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist’ comes to mind.

Leon’s far more political than Granada. Throughout the town huge murals depicting the revolution adorn just about every major wall, even the ones surrounding a concrete basketball court where young people are playing. The town is decked out in black and red. Slogans supporting Daniel Ortega are everywhere. You can buy a red and black soccer jumper with Ortega’s name and the number 11 for his 2011 election victory at every second stall around the main square.

The square is the hub of the town. Opposite the museum is the cathedral, the largest in Central America. Its facade towers over the square. On these hot summer nights, people stroll around the square in the cool night air. El Sesto, overlooking the cathedral is the perfect place to enjoy some good food and watch the world go by.

•

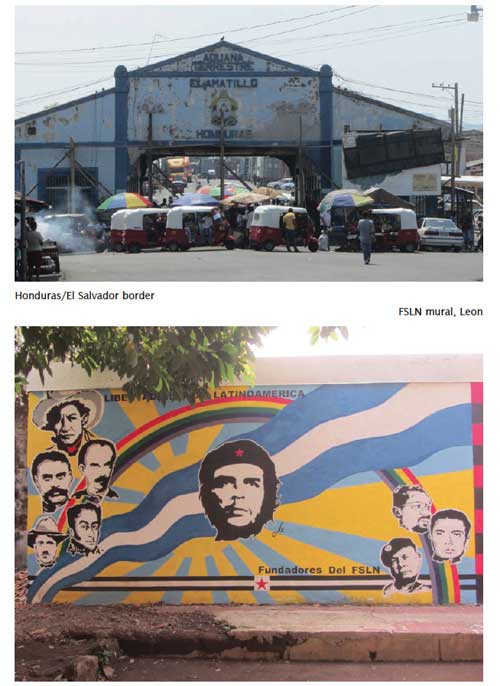

Another day, another border crossing. After soaking up the history of Leon we’re moving to Honduras. We have to pay $2 each to leave Nicaragua. Now that’s a first!

We ride into Honduras and the first person to come up to us is an English speaking fixer who wants $10 to help us through the border. These constant border crossings are becoming wearing, so we go for the soft option and take the fixer.

Again we find ourselves making many small donations to the local economy. Immigration costs $6 but the office won’t give us any change from $10. Customs want $6 each but accept $10 rather than $12. The money goes straight into his bottom drawer. There aren’t any receipts on offer.

We get some of the local lempira, but not much. We don’t want to get stuck with it as it only has souvenir value outside of the country and is hard to exchange for any other currency.

Honduras is another overnight stop, like Costa Rica. We avoid the cities and ride the Pan American Highway along the coast to the village of San Lorenzo and look for the so-called ‘best hotel in town’. It’s run by a local woman and her American husband who sits in a room near the hotel gate and watches the world go by from his bed. He’s clearly very ill.

The locals say it’s dangerous to be outside the hotel compound at night. That’s okay. The hotel restaurant has good, cheap food and a cool breeze coming off the Pacific. We’re happy to stay in.

•

One night in Honduras, now we cross into El Salvador. The fixers are everywhere. One young man offers to help us through the Honduras side for just $3. This turns out to be $10 because he has to pay his friends. $10 isn’t much for us but it’s a lot for them. This notion helps us feel better about constantly putting our hands in our pockets. Shirl manages to exchange our lempira for US dollars and we feel pretty good about this border.

Then we hit El Salvador.

I come out of the immigration office to find Shirl giving one of the officials the rounds of the kitchen. She’s incensed. There’s a starving dog that barely has the strength to eat the food she has bought him at the border café. The immigration official admits the dog lives at the border yet they don’t feed him. Shirl doesn’t hold back. She tells him it’s a disgrace and he should be ashamed. ‘One day you will arrive at work and find the dog dead,’ she tells him.

She’s obviously had a gut full of the way the animals are neglected. I agree with her, but I’m quietly glad we’ve already passed through the immigration process before she launches her attack.

When we get to the customs area Juan, the fixer, comes in very handy. It’s tucked away in a small office behind a loading dock. A semi-trailer is being searched and hundreds of parcels of toilet paper are being unloaded.

A fat policeman waddles into the customs area and gives Juan a nod. Juan says the policeman expects me to pay him $40 to ‘make the paperwork go quickly’. Juan claims the police can hold us up at the border as long as they like.

My blood boils. I’m not happy. I know corruption is a way of life here and successive governments have done nothing to stamp it out. It’s now ingrained in the culture but enough is enough. Juan will probably get a sling from the copper as well as the money he expects me to pay him. I tell Juan I’ll pay him $10 rather than the $6 he asked for and that’s all. The fat copper gets nothing. He’s not happy but can see I’m not budging. Bad luck.

The paperwork doesn’t take hours and we get through without paying the bribe to the police officer. We’re right to go, but not the truck driver. He’s still waiting for all of his toilet paper to be reloaded. He tells Shirl he’s prepared to wait rather than pay the police. Good luck to him!

Shirley: On the Pacific Coast at La Libertad we find the Pacific Sunrise Hotel, overlooking the ocean with a wonderful pool. It’s been hot and we’ve been rushing along so it’s time to take a day off the bike and do nothing. This is just the place.

A day by the pool sipping cool drinks, snoozing in the sun and watching the sunset into the Pacific is a real tonic.

•

Brian is over the moon about the bike’s fuel consumption. We’ve done 600 kilometres on this tank and the computer says we can go another 200. We’ve crossed most of Nicaragua, all of Honduras and most of El Salvador on one tank.

Next stop — Guatemala.