12 October – 5 December 2012

Brian: Öhlins has organised for the replacement shocker to be fitted at Kais Suspension, a family business that specialises in Öhlins shockers for race bikes, in Manchester. It doesn’t take long for them to fit the new one, a later model of the one that snapped in British Columbia so many months ago. They even clean the one that’s come off the bike and organise to ship it home for us. Service with a smile — thanks Öhlins.

We’re spending a couple of days with our friend Liz and her husband Jed in Manchester. We met Liz through our good buddy Phil in Australia a couple of years ago. She’s gregarious and loves a laugh. We hit it off immediately. Liz welcomes us with champagne and that sets the tone of our time together, wining and dining our way through the northern city.

Even though Liz is bored to sobs by soccer she takes us to the Manchester United home ground. It’s actually an interesting tour of the change rooms, premium seats, manager’s box and the hallowed turf. You can look at, but can’t touch, the turf, it’s so precious. You can buy literally anything in Manchester United colours in the shop. For once Shirl has no interest in spending money. It had to happen.

Shirley: It’s doctor time again. We took six months worth of medication with us from Australia, topped that up in Texas and now it’s time to check out the National Health system. We presume we’ll be covered because we’re Australian citizens travelling on Australian passports; after all, Australia is still part of the Commonwealth.

Not so. Reciprocal rights only apply to holders of EU passports. The Commonwealth doesn’t count for much anymore. We don’t even have our own queue at the airport.

We pay £65 (about $110) to go to the doctor and for our scripts, then another £60 (about $95) for six months’ worth of drugs. This includes the malarial medication we’ll need in Africa and a top-up of our broad-based antibiotics that we keep for emergencies. It’s still cheaper than Australia. And the good news is that Brian’s blood pressure is perfect.

It’s been a great couple of days but we need to get on the road and Brian needs to track down the ferry from Turkey to Egypt.

On our way to London we pick up some spares for the audio system in our helmets and new pannier bagliners. The months on the road are taking their toll, with the old ones ripping at the seams.

•

Back in 2003, at the start of our ride, we met Trent and Jacqui Whitta at the Horizons Unlimited meeting in England. These young, friendly Kiwis have been living in the UK for more than a decade, apart from the couple of years they packed everything up, got on their bikes and rode home to New Zealand. It wasn’t long before they flew back to London where the work opportunities were so much better. It was a chance meeting at Horizons Unlimited but it’s grown into a firm friendship even though, yet again, there’s an age difference of about 15 years. They’ve visited us in Australia and we’ve stayed with them here in London a few times over the last 10 years.

Since we last saw them, Trent and Jacqui have adopted four-year-old Summer and six-year-old Martin, and we’re excited about getting to meet them. These kids haven’t had the best start in life and Jacqui and Trent have so much to offer.

Our timing couldn’t be better. Trent’s picked the kids up from school and Jacqui is walking down the street when we arrive. The kids are amazing. They’ve been told all about us, but the thing that they’re most interested in is the bike, especially Martin, who’s bike mad.

The years since we last met just fade away as we talk and talk and then talk a bit more.

Brian: When the kids leave for school and Jacqui and Trent for work I hit the computer. I’m now in two minds about this next ride. Reading other travellers’ blogs and the Horizons Unlimited webpage it seems that getting a motorcycle through Egyptian customs can be tricky, to say the least. It has to be registered in Egypt but that’s the easy part. From what I can find out there are palms to be greased at every turn and even that doesn’t mean an easy transition from freight item to on the road.

Shirl and I have discussed all the options. One is flying the bike from London to Cairo. The physical act of flying the bike isn’t a deterrent, but the bureaucracy and bribes at the other end are. Not being with the bike has got to pose more problems than being with it on a ferry, and the ferries from Italy are definitely not running.

The ‘ride across North Africa’ option is too difficult because of the new regime in Libya. Dictators certainly make getting across difficult countries a lot easier. (Just joking.)

The other option is the ferry from Turkey. We could dash across Europe in a few weeks to get to Turkey but why would we bother? After a year on the road that doesn’t seem at all appealing. And there’s the question of weather. We’ll need to get over mountains and winter is around the corner.

And from what I’ve been reading there’s no guarantee that ferry will be running anyway. There seem to be problems with its schedule too.

•

Jacqui’s brother, Peter, comes around for dinner. We met Peter at the same Horizons meeting. This tall, thin biker is very relaxed about life. Back in 2004 he travelled across the world to work with a bike tour company in Goa, India. We stayed with Pete there and he’s stayed with us in Melbourne. It’s an amazing night, like we’ve always known the trio and see them every day — not every couple of years.

Shirley: Our second camera has given up the ghost. Luckily, the son of a good friend of ours in Melbourne, Kim, is working for Canon UK and organises the latest model of our little camera. Even though it’s compact and idiot proof it’s got a fantastic zoom which is just what we’ll need when we go on safari in Africa — if we ever work out how to get there.

•

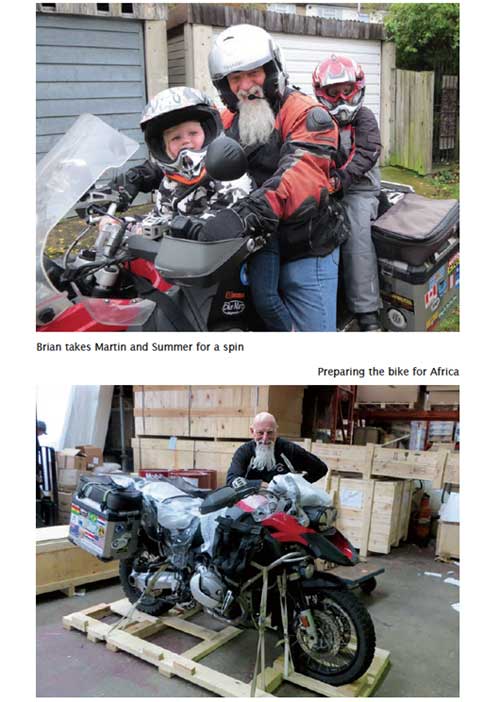

On Sunday morning Brian takes Martin and Summer for a little ride on our bike, starting in the laneway at the back of the house. Summer gets on the tank and Martin on the back. They both have good bike helmets and boots and just love it. Summer can only go around the block and not on the streets. When it’s time to get off she cries because she isn’t big enough to be on the bike on the road. She says it just isn’t fair. It must be hard being four.

Brian: It’s decision time. The final straw is reading that the ferry from Turkey to Egypt is involved in a financial dispute and it’s not clear when it will begin running again. I’ve heard that some travellers had cleared customs and were in the holding yard at the terminal when the news came through and are stuck there.

No ferry from Italy; doubtful ferry from Turkey. To fly is certainly possible but the bike might be held up in red tape. A transit visa through Libya would only give us three days to get across the country and we’d need a Libyan guide, which would mean paying for him and his car.

If it was the start of our trip I’d probably bluster my way through, but it’s not. We’ve been on the road for a year and I’m missing my extended family, especially my boys, their wives and the five grandchildren.

We’ll fly the bike to Johannesburg and explore southern Africa before heading home. That’s giving us the best of both worlds — safari without the stress.

Shirley: I know Brian is bitterly disappointed and I’m surprised by my own feelings. While riding through Africa was something I was concerned about, I’m upset we won’t get to Egypt. Before my sister, Fran, died from cancer in 1996 we’d planned to visit Egypt together with our husbands. It was one of the ‘if onlys’ in her life. She didn’t get to see the pyramids. It’s something I’ve always vowed to do and now I’m worried that we won’t see them either. Brian promises to take me to visit the pyramids one day, to fulfil Fran’s dream.

Brian: We’re going riding now while we sort out getting the bike from the UK to South Africa. We head south to Winchester to visit Ollie, who we met in Alaska. Then it’s the coast of Cornwall. It’s getting cold already but we’re going to make the most of it.

I’ve been checking out places to visit in this part of England and found Tintagel, where the legend of King Arthur was born. The roads for the last 16 kilometres are so narrow and enclosed I have to take extra care going around blind corners. Stone walls are only centimetres from the road. There’s no run off so I hang wide on every turn. I think the GPS has finally lost the plot as we track onto narrower and narrower roads and lanes.

The ruins of Tintagel Castle, perched on the windswept headland, look down on the town which I discover is the home of the Cornish pasty, one of my favourite snack foods. Shirl’s had her fill of Tex Mex in the US now it’s time for my tastebuds. There’s a shop on every corner selling these tasty little pastry parcels. I want to check them all out before I decide where to make my purchase.

While we’re wandering Shirl spies a photo of Martin Clunes as ‘Doc Martin’ in a shop window. Surely this isn’t the fictitious town of Portwenn from the Doc Martin television fame? She’s filled with enthusiasm, tracking down the facts.

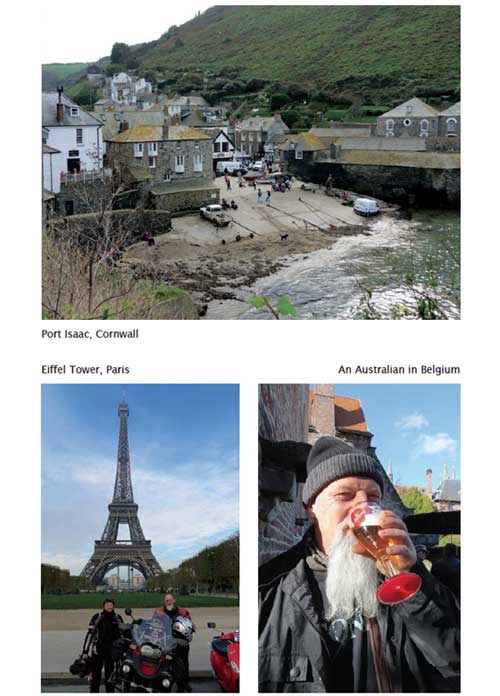

Port Isaac’s the town and it’s only about 15 kilometres down the coast. There’s no stopping her now. The Cornish pasty has to wait.

Shirley: I love Doc Martin. Riding into Port Isaac it’s obvious I’m not the only one. Brian rides down a narrow street towards the water and we can only just squeeze through the crowds of pedestrians. I’m not sure if the road is open to traffic, but that doesn’t deter Brian.

I’m rapt. There’s the school where Louisa works and across the bay is Doc Martin’s home and the surgery.

There’s certainly nowhere to park so we ride back through the crowds and find a car park on the edge of the cliff. Walking to town we pass a coffee shop that has posters of Martin Clunes in the window and sells exorbitantly priced tea towels bearing his image.

Past the ‘school’, which is actually a restaurant, we get to ‘Mrs Tishell’s pharmacy’, which is an ice cream and lolly shop. The owners are proud of their part in the series and boast that the television crew takes over their shop and the residence for the duration of the filming. They even appear as extras in the doctor’s surgery. We’re also let in on a secret. They can sell souvenirs with a line drawing of the ‘Doc’ but not with a photo of Martin Clunes. The reason why? Only the coffee shop at the top of town has paid for the rights to use Martin’s image.

Now we better get back to Tintagel so Brian can get that Cornish pasty.

Brian: It’s taking some organising but it looks like we’ll be able to fly the bike from London Heathrow to Johannesburg. The only drama, as far as I’m concerned, is the need for the bike to be in a crate rather than roll on/roll off like the flight to get here from Canada. I’ll fight that battle, but now we’re heading to Europe for a few of weeks.

Getting there is simple. We take the train. We’re held back until all the cars and buses are on the Channel Tunnel train. On board we put the bike on the side stand, leave it in first gear and park the nose into the side of the carriage. Thirty-five minutes later we’re in Calais. Shirl fills in the time reading the French phrasebook.

It’s bloody cold in Calais — just 5°C and there’s snow on the side of the road. This reinforces our decision not to make the dash to Turkey. It’s too late in the season.

We’re on our way to visit friends in Frankfurt. We take the scenic route through Bruges and Maastricht, made famous by André Rieu. They’re both rather beautiful towns, filled with history and fine buildings.

The rain is pelting down when we get to the junction of the Moselle and Rhine Rivers at Koblenz. It’s so cold my fingers are freezing even with the heated handgrips on. Next stop is St Goar, a picturesque 16th century town on the banks of the Rhine.

Overnight a message comes through from my old mate Brett; his dad, Roger, passed away after a long illness. Brett and I grew up together and Roger was a huge influence on me. Brett was there for me when my dad died and was one of the pallbearers at his funeral. It makes me feel so far from home, not being there for Brett. Sad days.

Shirley: We first met Tonya Stevens in the early 1990s through the Fitzroy Football Club when she was barely out of her teens, a dedicated young woman with a passion for the ill-fated football club and workers’ rights through her job in the trade union movement. Now she’s glamorous, very much the European sophisticate, working as a tour guide of her adopted home in Frankfurt. Her husband, former Victorian politician André Haermeyer, has retired from politics and seems to be thriving on life in the country of his birth.

They arrived in Frankfurt with their most prized possessions, Munchy and Paris, two very spoilt Australian cats. Their apartment is bright and airy with two balconies, one covered in wire mesh, making it a safe outdoor area for the cats.

We enjoy Andre and Tonya’s company from the minute we walk in the door. They couldn’t be better hosts. We’re treated to the local speciality, apfelwein served in a bembel, and traditional küchen (cake) served with champagne rather than coffee. Of course, we sample sausage in bread rolls. And for a special treat we go to the Mozart Café where the milkshakes have real chocolate mixed with the milk and the hot chocolate has a dash of chocolate liqueur.

Tonya’s love of this city is obvious when we take her tour. Recognised as a financial centre, so many visitors just pass through Frankfurt’s airport on their way to other cities. They don’t know what they’re missing. While much of the city was destroyed during the war much has been rebuilt because the people of Frankfurt were keen to preserve their literary and intellectual standing in the world.

I’m moved by the city’s symbolic memorial to the night the Nazi students burnt the books, empty bookshelves set under an opaque paver in the city square. The lives of the 120,000 Jews who were removed from the city are remembered in a wall around the old Jewish Cemetery. The city is certainly keen to repent for the sins of the past. Among those remembered are Anne Frank, her sister, mother and father.

Tonya introduces us to her favourite fruiterer at the local market. He helped when she was learning German, teaching her the names of fruits, vegetables and herbs.

Brian: We jump on a train to spend the day in Heidelberg. It’s a wonderful city that wasn’t bombed during the war because the weather was bad on the day of the planned raid. The city did lose its bridges, but they were blown up by the Germans to prevent the allied advance. There are wonderful views of the city and the river from the Schloss.

For dinner we go to the Red Ox, one of the oldest pubs in town. Built in 1703, the student pub has thousands of names carved on the tables and walls over the centuries.

•

It’s our last night together. We’re sitting around the dinner table, after enjoying a spectacular Sicilian lamb stew cooked by André, when he produces his iPod. For the next few hours we listen to our favourite Australian tracks from the 60s, 70s and 80s. What a night! The four of us all miss home tonight.

•

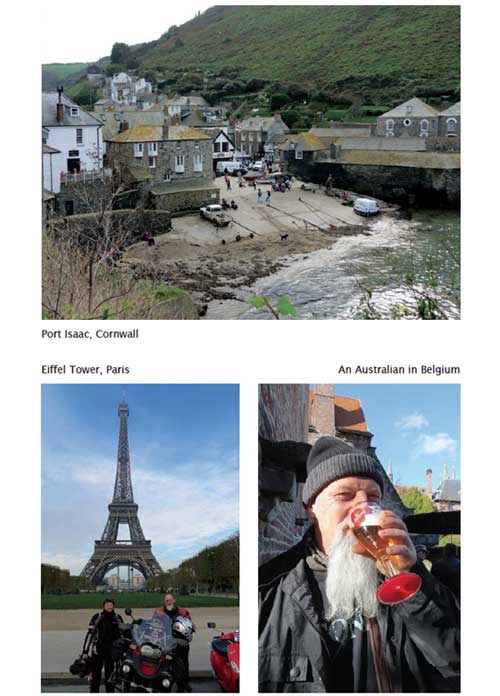

Gay Paree! Paris is one of our favourite European cities, yet we’ve never been here on a bike. The one thing I want to do is ride along the Champs Elysees and around the Arc de Triomphe. It’s special to ride past Notre Dame, the Eiffel Tower, the museums and the Seine.

We cross Shirl’s favourite bridge, the Alexander III, go between the Grand and Petite Palaces and we’re in the manic traffic heading up the Champs Elysees. It’s slow going until I take the bit between the teeth and do what all the Parisian scooter and bike riders do — split the traffic, ride on the wrong side of the road and ignore pedestrians! No one seems to care.

Some riders are smoking cigarettes, others cigars and one is puffing on a pipe, as they negotiate the crazy traffic.

At a pedestrian crossing, a scooter coming the other way is on the middle white line and so am I. He indicates for me to go first. It’s all very polite. I notice he has a beard like mine, only his is plaited. Hmm — there’s a thought.

When we get to the roundabout at the Arc de Triomphe Shirl fends off the cars, giving motorists who make a bit of space for us to get through a wave.

It’s manic and crazy and there’re no rules, but it’s fantastic.

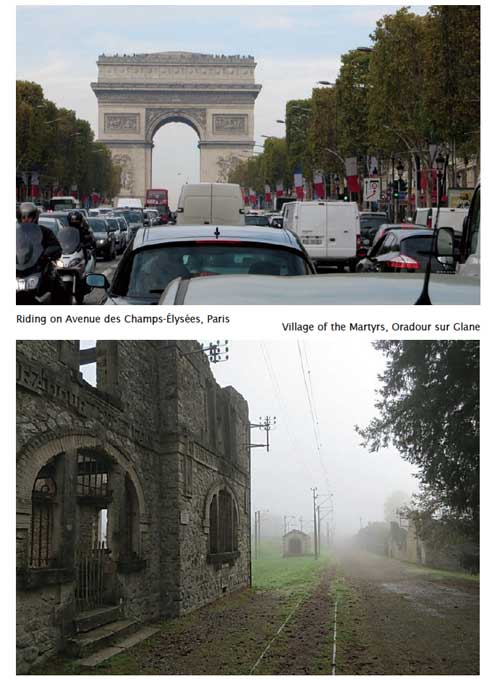

Shirley: We’re in Limoges and Brian’s not keen on a visit to the porcelain factory. Flicking through the brochures at our hotel I find reference to the Village of the Martyrs — Oradour-sur-Glane.

On June 10, 1944 a tragedy occurred here, so harrowing President De Gaulle declared the town would never be rebuilt on this spot because, ‘The memory must be kept alive, for a similar calamity must never occur again.’

On that day more than 600 men, women and children were massacred by the Waffen-SS before they set fire to every building in the town. Only a handful of people survived.

A thick fog has descended on Oradour-sur-Glane. It’s only 1°C and the ice warning on the bike is flashing.

You can’t see the old town from the road and enter it via a pathway from the museum that leads to the main street. The fog adds to the chilling atmosphere. More than 300 buildings were razed — the entire town. Today it’s a ghost town. The remaining stonewalls are blackened by fire. Where there were once windows there are now just holes, opening into what were once homes and businesses. Twisted metal bicycles, prams, beds, tables, ovens, pans and sewing machines litter the shells of buildings.

Cars were left where they were parked when the town burned, now slowly eroding with time. The town doctor’s car is still parked where he left it to make a house call. We walk past the garage, school, hotel, cafés, the butcher shop and the hairdresser. The town is just as it was when the Nazis drove away the day after their dirty work.

The only sound is the crunching of our bike boots on the pathways and streets. We’re both deeply moved, particularly by the items recovered from the town and now on display in a memorial — the ink wells from the schools, toys, reading glasses, pocket watches and a toy pedal car.

Inside the shell of what was once the town’s church it’s easy to imagine the women who were rounded up and trapped inside as it was set alight.

What makes this tragedy even more devastating is there were French, Vichy French, among the troops.

Man’s inhumanity to man …

Brian: The bitter cold and persistent fog make me realise we made the right decision not to head to Turkey. Instead we go south to Spain for some better weather. Our first stop is a café in a little town just over the border. There are photos of motorcycle racing champion Carlos Checa on the walls. In broken Spanish I find out he has a villa nearby and often drops in for lunch, but not today.

The sun breaks through late in the morning and it turns into one of those magic days on the road. The sun’s shining; the road is twisty with very little traffic. We hit the edge of the Pyrenees.

There are plenty of tunnels through the mountains — two kilometres, four kilometres and five kilometres cutting down our journey time. It’s not cheap, though — the longest costs €11 (over $16.00) — and we spend more on tolls than fuel today.

Barcelona is a troubled city. Workers are revolting against the banks that are foreclosing on mortgages at a time when people are struggling to pay their bills because of the austerity measures introduced following the Global Financial Crisis. Unemployment is running at 26 per cent and people are being evicted from their homes. There’s been mass violence on the streets in cities around Spain.

A national general strike has been called and our hotel advises we stay inside today. Imagine saying that to a retired policeman and a journalist who cut her teeth on police rounds. Despite the warnings we venture out. We did something similar in Esfahan, Iran on ‘Down with America day’ so why not here? The demonstrators on that day weren’t concerned that foreigners, even western foreigners, were watching their anti-US protest.

We’re sure it’ll be the same here, today. Packs of demonstrators are walking the streets, going from bank to bank, chanting, blowing whistles and occasionally letting off massive fireworks. Some are banging pots and pans together. We feel their sense of despair, anger and frustration.

Apart from the fireworks, the crowd isn’t violent, but there’s a huge police presence on the streets. Brawler vans, police in riot gear and wearing balaclavas look pretty confronting, but the crowd don’t seem to care. And the police aren’t fussed when I take photos of them.

There’s an upside to the demonstrations. No public transport and no business activity means we can take in the splendour of architect Antoni Gaudi’s buildings without being jostled or run over.

His most imposing work is the Sagrada Familia, the futuristic basilica commenced in 1882 and still not completed. Towering arches, modern stained glass reflecting a myriad of colours across the huge interior, an exterior adorned with gargoyles, animals and flowers all meld into a fascinating building.

I sit for a while and reflect on loved ones, particularly my dad and Roger our neighbour all those years on the next fruit block. It’s inevitable that we’ll die, but for me it’s what you do with your life, what you experience and what you leave behind that are important. Life is for living, that’s why we’re on this adventure.

In the evening the streets are deserted and so is the Flamenco theatre. There are only four of us in the audience. It seems everyone thought the show would be cancelled because of the strike. The performers outnumber the audience two to one. It must be demoralising for them to perform this most sensual dance to a handful of people. No matter how loud we shout, the olés sound very hollow.

•

The road south reminds me of the tiny town on the Murray River where I was born, Merbein — the rich, red soil, orange trees with lush verdant foliage and huge, ripe fruit. The Spaniards are obviously keen on alternate energy. We pass massive banks of solar panels that seem to power factories and there are huge wind farms. It all makes sense — using the natural resources.

We take a break at Oliva by the sea to visit the family of a drinking buddy of Brian’s. Kevin’s daughters, Clare and Amanda, make us feel very welcome in their bar which is filled with ex-pats watching European football. After a couple of days at the beach we’re ready to hit the road again.

Shirley: Surfing the net I see a photo of the Zaragoza Basilica del Pilar and convince Brian this is as good a way as any to head back to France at the end of our brief European sojourn. We avoid the main roads and their exorbitant tolls and enjoy the ride through the small villages much more.

The Basilica del Pilar is an amazing building with domes, towers and tiled rooves built right on the Ebro River. It’s getting dark and the Basilica’s unique roofline is etched against the night sky. It’s as wonderful as it is unique.

Across the road is a little café in a palatial room with cast plaster ceilings and enormous mirrors. I order a hot chocolate expecting a chocolate flavoured milk drink. Instead I get a cup of hot, thick sauce, that’s just melted chocolate. It’s tasty and sweet and sickly all at the same time. One is enough for a lifetime.

The harsh financial situation in Spain is very evident here. There are beggars everywhere, but they’re not wasters or druggies — they’re families, young couples with their pet dogs, old men, young men. These are desperate times. Brian gives to a man with a photo of his children. We’d like to do more, but we can’t help everyone.

Despite this Zaragoza has a good vibe. An old lady on a walking stick comes up as we’re loading the bike. She has one message for us — you only have one life to live so live it. It’s pretty much our ethos.

Zaragoza now ranks among our favourite cities in Europe along with Paris, Barcelona and Bruges. Despite the biting cold on the bike it’s been well worth the effort to come down here.

Brian: Back in France the weather is getting more like winter. There’s just one more place before we head to Calais and the train to England. Caen.

The Memorial of Caen is a museum that explores World War II, and not just from the Normandy landings. It looks at how the war began and how it played out for the people of Europe, especially the French. It begins with the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918, follows the financial problems of the restructuring of Germany and the emergence of Hitler and Mussolini. We read with horror about the treatment of the Jews, gypsies, intellectuals and all those interred and murdered. It also deals with the Vichy French and how they turned against their own people and even participated in wiping out members of their population as they did at Oradour-sur-Glane.

By the time we leave it’s dark and our bike is the only vehicle left in the car park. I have to use the light of the GPS to unlock the helmets.

It’s Sunday and most of the restaurants are closed but there’s an old English double-decker bus across from the hotel. It’s a pizza restaurant with seating upstairs and a takeaway window. The downstairs section has been converted into a kitchen. With a piccolo of red wine we head upstairs. The safety-crats haven’t arrived here yet. I can’t imagine you getting a permit to have a restaurant without an escape route above a kitchen cooking with gas. It’s a firetrap. Safe or not, the restaurant is very groovy and the pizzas are remarkably good.

Caen isn’t famous for just its unusual pizza restaurant and museum. William the Conqueror lived here and made it his power base. The Men’s Abbey, Women’s Abbey and cathedral are impressive.

On the way to Calais I ride along the beaches made famous by the World War II allied landings. It’s cold and blowy — very different to the weather in June when the D Day landings took place.

The museum gave us an insight into the dilemma faced by the allies. Because the Germans had many major communication points in this area it was brutally bombed. It must have been very hard on the innocent bystanders — the locals.

Now we need to organise the bike to fly to South Africa. The freight company is insisting on the bike being crated, which is a bloody nuisance. To have one built is going to cost £300 (about $520.00) so I ring West End BMW where they just throw out the crates when new bikes arrive from Germany. They’ll save one for us, if a GS arrives. But it’s a big IF.

Shirley: The forecast for England is bleak so we’re pleasantly surprised when it’s bloody cold but dry as we ride out of the train at Dover.

The bike needs another service and the rear drive seal is weeping. It needs to be replaced — again. It’s an interesting ride to BMW. Brian’s so used to riding on the right hand side of the road we end up on that side a couple of times. He corrects before we get into any trouble.

There’s been no GS delivered so there’s no crate, but they have a base for another model that should be OK. This will mean strapping the bike onto the base, like a pallet, rather than completely crating it. I panic, saying they’ll refuse to carry the bike if it’s not crated. Brian’s not concerned. We’ll strap it on the base and see what they say.

To get the base to the freight yard we need to hire a truck. The costs are mounting. After months in North America we’re used to customer service, a concept that seems to have disappeared in many parts of England.

Take Europe Car for example. When we ring their customer service number it has an automated response telling us what numbers to press. It doesn’t matter what we press we always end up in the corporate area where they can’t or won’t transfer us to someone who can help. We walk to the nearest depot while the bike’s being serviced and the man at the customer service desk couldn’t be less helpful. They don’t have any vans and even if they did we couldn’t leave the bike in their yard while we use the van. Right.

The next morning Brian hits the phones and organises a truck from a smaller company not far from Jacqui and Trent’s. It’s freezing this morning, literally, so it’s good to crank up the heater in the truck.

With the crate base in the back we head to Heathrow airport and the freight terminal. They’re expecting us and they’re expecting a crate. In the end, the manager says it’s up to us if we want to take the risk. We have no choice.

We pass a bookshop and I cajole Brian to let me buy a Southern Africa guidebook. We used eBooks in Canada and the US and I didn’t like them. I promise I’ll fit it in my pannier, but he doesn’t look convinced. I’ll make it fit.

Brian: The bike’s prepared for its flight, strapped onto the crate base and bubble wrapped. Every extremity is covered in the plastic to protect it as best we can. We still haven’t seen the paperwork but have been told it will be okay. The dangerous goods certificate is here, so that’s a start. The workers at the freight terminal tell us to lock the panniers and assure us all will be well, the bike will be in South Africa the same day as us.

It all seems to be going smoothly until the agent rings to tell us he needs the bike keys so the panniers can be inspected by Customs. Oh great. We need to organise a courier to collect the key and take it to the agent’s office. We’ll get it back when we arrive at the airport tomorrow.

It really seems like the left hand doesn’t know what the right hand is doing. Imagine if the bike was in a crate? How would they inspect it then?

•

It’s snowing, the first snow of the season.

It’s time to leave after about 6,500 kilometres around Europe. We’ve ridden 70,704 kilometres through 25 countries.