Corporal Samuel Fuller in Sicily during World War II, flanked by a pack mule and a young boy. Mules and children pop up in almost every Fuller combat film. Chrisam Films, Inc.

A man eyes a woman on the subway. She returns his gaze. Two other men watch. A pocketbook is picked.

An outlaw shoots his best friend in the back, then proposes to his girlfriend.

A woman furiously beats the camera with her bag to the sound of wailing saxophones. Her wig falls off. She is bald.

An African-American pulls a white pillowcase over his head and cries, “America for Americans!”

A woman’s face cracks like a broken mirror, shattered by a gunshot.

A young solider pumps round after round into a Nazi hiding in a concentration camp oven.

A newspaper editor pummels a man against the base of a Benjamin Franklin statue.

A sergeant shoots a prisoner of war, then yells at him, “If you die, I’ll kill you!”

With their startling subject matter and emphasis on conflict, contradiction, and kineticism, Samuel Fuller’s films are designed to hit you—hard. His stated goal was to “grab audiences by the balls!” By upending expectations, disregarding conventional norms, and combining realism with sensationalism, violence with humor, and intricate long takes with rapid-fire editing, Fuller created films that produce a direct emotional impact on the viewer. He wanted to unsettle the assumptions of audiences, to surprise them, to instruct as well as to entertain, always striving to reveal the truth of a given situation. His are daring and stimulating films, and they have inspired fascination in generations of fans.

As the recurring narrative and stylistic tendencies in Fuller’s films are so readily apparent, his work has repeatedly been the subject of auteur study. In the late 1950s in France, the young lions at Cahiers du Cinéma discovered in Fuller a prime example of the delightfully aggressive nose-thumbing they celebrated in Hollywood’s genre pictures and began to describe his aesthetic as primitive. When structuralism inflected auteur criticism in Britain and the United States a decade later, a collection of essays edited by David Will and Peter Wollen for the 1969 Edinburgh Film Festival, as well as monographs by Phil Hardy in 1970 and Nicholas Garnham in 1971, refocused attention on the motifs, themes, and dichotomies in Fuller’s narratives, elevating his stature as one of the preeminent cinematic critics of American society.1

This book aims to rethink earlier portraits of Fuller by examining his films in the context of the practices and pressures of the industry in which he primarily worked: Hollywood. In doing so, I am following in the footsteps of scholars such as Paul Kerr, Justin Wyatt, Lutz Bacher, and others who have demonstrated the necessity of considering auteurship in relation to economic, industrial, and institutional determinants.2 I draw on in-depth formal analysis as well as previously untapped primary sources, including script, production, payroll, legal, and regulatory files; trade and popular publications; and interviews. This book focuses on Fuller’s directorial work in film, and as such necessarily neglects much of his vast written output for page and screen, as well as his television efforts. A particular emphasis is placed on understanding the narrative structure and visual style of Fuller’s films, as these topics have previously received little systematic analysis.

As a writer, director, and frequently, producer, Fuller had multiple means of creative influence over his films, a situation that was highly unusual for directors of his era, particularly those operating—as he often did—in the low-budget arena. Though he labored in a wide range of production circumstances for more than forty years, Fuller’s many-layered involvement in his films contributes to the distinctiveness of vision exhibited by the totality of his work. Within the history of American cinema, Fuller is the model of the idiosyncratic director, one whose films frequently push the boundaries of classicism, genre, and taste. His work contains the potential to reveal the contemporary limits of what is considered socially and aesthetically acceptable to present onscreen.

Fuller did not direct in a vacuum, however, and his filmmaking was molded by competing influences whose nature and weight varied over time. Fuller began his directorial career in the late 1940s during a transitional period in the American film industry marked by the decline of the studio system and the rise of independent production. The changes in Fuller’s working conditions and degree of production control allow for an examination of how economic, industrial, and institutional forces impact a director’s aesthetic tendencies. The recognition that multiple causal determinants shape the nature of Fuller’s work is crucial to explaining its variation in form and relation to classical conventions and production trends. Such an approach acknowledges the director as a conscious craftsperson engaged in formal decision making while constrained by rival concerns, providing an alternative to conceiving of authorship strictly according to the director’s biography, psychology, or choice of recurring motifs.

The length of Fuller’s career also enables an assessment of the opportunities and challenges facing directors in the decades following the 1948 Paramount antitrust decision, which prompted the major studios to cut payrolls and move toward financing and distributing independent productions. Rather than drawing all of their cast and crew, equipment, and other resources from a single studio, producers now assembled the means of production on a film-by-film basis, each time creating a distinct “package.”3 Fuller provides a case study of the impact of the shift to the package-unit system on a director’s films and career, revealing that operating as an independent producer or freelance talent—rather than as a director under contract to a studio—could both aid and frustrate creative expression and professional development. In particular, Fuller’s case complicates the promise of artistic freedom associated with incorporation as an independent producer while offering a corrective to popular conceptions of studio-director relations as obstructive to individuality and innovation. While the details of Fuller’s case are specific to him, the choices he faced when navigating the changing industrial landscape in Hollywood were shared by fellow directors emanating from the world of low-budget B movies. Industrial determinants can partially account for the fates of Anthony Mann, Budd Boetticher, Joseph H. Lewis, Phil Karlson, Andre de Toth, and Jacques Tourneur—gifted filmmakers who, like Fuller, struggled to maintain their careers by the 1960s.

Like cultists everywhere, Fuller followers tend to seize on those elements in his films and his biography that most excite and use them to proselytize the cause. So Fuller becomes a filmmaker ahead of his time; one who makes movies that reek of headline-blaring tabloids; who transforms every picture into a war picture; who is a primitive, an outsider, a maverick. There is some truth in these characterizations, but as a newspaperman would say, they don’t tell you the whole story. A close examination of Fuller’s body of work reveals greater variety and complexity than is generally acknowledged. My goal in this book is to account for the total Fuller: those films and portions of his career that match his legendary persona, as well as those that do not. While Fuller’s primary artistic impulses remained consistent throughout his professional life, the manner and means through which he expressed them differed over time. The following discussion of Fuller’s biographical legend, his aesthetic interests, and his working methods lays the foundation for a long-overdue analysis of his rich and influential legacy.

The Fuller Biographical Legend

Over the years, publicists, critics, and Fuller himself have shaped the details of his life and his career into a biographical legend, a persona that has influenced how his films are generally understood.4 At the heart of the Fuller biographical legend is Fuller’s own colorful personal history. Fuller began directing films only after successive stints as a journalist, solider, and screenwriter, and his real-life adventures clearly shaped his worldview and his work. As publicists and critics wrote about Fuller’s action-packed life and films, his legend took on a wistful, nostalgic quality; to many of today’s writers he is an icon of lost authenticity, a reminder of an era when American moviemakers learned about storytelling on the streets rather than in film school. Fuller’s biographical legend is further defined by his reputation as a “primitive” filmmaker and a maverick who worked outside of Hollywood studios, characterizations that gained popularity during the 1950s and 1960s and have been widely repeated ever since. The Fuller biographical legend foregrounds important aspects of his story but is only the beginning of our journey toward understanding his films.

Fuller’s first career was as a crime reporter in New York City, where he haunted the streets for the New York Evening Graphic, the town’s most sensational tabloid. In the midst of the Depression, he quit the paper and headed west, writing his way across the country until he landed a job covering the waterfront for the San Diego Sun. Fuller’s journalism provided the foundation for three pulp novels he wrote during the late 1930s and enabled him to begin collaborating on film scripts and submitting story ideas to Hollywood studios. From his years as a newspaperman Fuller learned the value of a punchy lead and the importance of speaking the truth. He frequently cited this period as providing significant fodder for his screenplays, and from the late 1950s to the present, critics have highlighted the tabloid flavor of his films.5

In December 1941, while writing a new novel, The Dark Page, Fuller enlisted in the army. At age thirty, he left behind journalism and Hollywood for World War II. Fuller served with the Twenty-sixth and Sixteenth Intrantry Regiments, First Infantry Division in North Africa and Europe, landing on Omaha Beach on D-day and participating in the liberation of the Falkenau concentration camp in Czechoslovakia. Fuller kept a diary during the war and incorporated many of his infantry experiences into the screenplays of his combat films, culminating in his autobiographical triumph The Big Red One (1980). Fuller’s years as a soldier fueled his subsequent reputation as an action-oriented director who made authentic, real-life movies. Fuller suggested the impact of his war years on his cinematic worldview during his cameo appearance in Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le fou (1965): “Film is like a battleground: Love. Hate. Action. Violence. In a word, emotion.”

Corporal Samuel Fuller in Sicily during World War II, flanked by a pack mule and a young boy. Mules and children pop up in almost every Fuller combat film. Chrisam Films, Inc.

The years Fuller spent in Hollywood immediately after the war taught him the importance of acquiring production control over his own stories. The screen rights to The Dark Page had been purchased by Howard Hawks; Hawks later sold the rights to the newspaper murder mystery, which Phil Karlson eventually directed as Scandal Sheet (1952). Three different studios then hired Fuller to write original scripts, all of which exhibited the hard-boiled sensationalism characteristic of his later films and none of which were produced. Despite concerns regarding the controversial nature of his stories, Fuller remained in demand as a screenwriter, even resisting a contract offer from MGM in the hope that he might be able to direct his scripts the way he wanted. Finally, in 1948, Fuller received a phone call from Robert Lippert, a West Coast exhibitor and independent producer, who offered him the opportunity to helm his own feature.

Over the next sixteen years, Samuel Fuller made seventeen films, operating both as a contract director and as an independent producer, much like fellow action experts Robert Aldrich and Anthony Mann. He wrote and directed three low-budget films for Lippert Productions, eventually receiving producer status and significant production autonomy: I Shot Jesse James (1949), a psychological western; The Baron of Arizona (1950), based on the true story of a nineteenth-century forger; and The Steel Helmet (1951), the first Korean War picture released in the United States. The astounding critical and commercial success of The Steel Helmet catapulted Fuller to the attention of the major studios as a hot new director of action genres.

The creative energy of production head Darryl Zanuck drew Fuller to Twentieth Century–Fox, where he signed an option contract as a director and screenwriter. Fuller wrote the original script for Fixed Bayonets (1951), his second Korean War picture, but shared screenwriting credit on his subsequent directorial efforts at the studio: Pickup on South Street (1953), a gritty espionage and crime thriller; Hell and High Water (1954), a submarine adventure; and House of Bamboo (1955), a cops-and-robbers picture set in Tokyo. While on leave from Fox, Fuller produced, wrote, directed, and completely self-financed Park Row (1952), a sentimental yet raucous view of the newspaper business in late-nineteenth-century New York City. Though he mounted an extensive promotional campaign, the picture flopped.

In 1956, after Fuller parted ways with Fox, he established Globe Enterprises, an independent production company, and initiated a series of financing and distribution deals with RKO, Fox, and Columbia. In addition to two failed television pilots, Fuller wrote, directed, and produced six films under the Globe banner: Run of the Arrow (1957), China Gate (1957), Forty Guns (1957), Verboten! (1959), The Crimson Kimono (1959), and Underworld, U.S.A. (1961). Following the collapse of Globe, Fuller worked as a freelance director on the World War II combat picture Merrill’s Marauders (1962); he subsequently wrote and directed two adult exploitation films for Allied Artists, Shock Corridor (1963) and The Naked Kiss (1964), neither of which produced sizable domestic returns. In 1965, Fuller left Hollywood for Paris to write and direct a science-fiction adaptation of Aristophanes’s Lysistrata, but the film never got off the ground. Unable to acquire financing for independent production in the United States and finding freelance directing work only on television, Fuller increasingly immersed himself in his writing.

Although he wrote countless scripts and treatments over the next twenty years, Fuller directed only six subsequent films and disowned one of them: Shark! (1969, from which he removed his name after losing control of the editing), Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street (1972), The Big Red One, White Dog (1982), Thieves After Dark (1984), and Street of No Return (1989). Ironically, his production decline was accompanied by his critical ascension, and young directors such as Wim Wenders and the Kaurismäki brothers kept him busy throughout the 1970s and 1980s with acting jobs in their movies. Even as Fuller struggled to find financing and distribution for his films, his difficulties only further clinched his reputation as a rebel, one too challenging to be embraced by Hollywood studios. After a debilitating stroke, Fuller died in 1997 at age eighty-five.

While Fuller’s biography has played a dominant role in critical assessments of his work, early characterizations of him as an artistic primitive and a Hollywood outsider have also proven a resilient part of his biographical legend. Critics in the 1950s and 1960s associated the seemingly untutored visual quality and emotional authenticity apparent in several of Fuller’s films with a primitive approach to filmmaking, a notion that in one form or another dominates discussions of his work to this day. In addition, beginning in the 1960s, newspaper profiles highlighted Fuller’s struggles as a low-budget independent producer and developed his reputation as a maverick. Through repetition over time, the labels of “primitive” and “indie maverick” have become the primary touchstones for critical discussions of Fuller.

Critics who draw on the concept of the primitive to describe Fuller’s style typically aim to valorize his often nonclassical aesthetic. According to one definition, a “primitive” artwork that appears instinctive and immediate rather than carefully constructed according to classical rules acquires an aura of primal emotion, sincerity, and originality.6 It is precisely this notion of simplicity and spontaneity as more emotionally compelling than the normative style of classical cinema that many critics respond to in Fuller’s work. In a 1959 Cahiers du Cinéma article, Luc Moullet initiated the critical association of Fuller with the term by describing him as an “intelligent primitive.” Fuller’s ignorance of film school conventions and reliance on his own instincts, Moullet argued, enable him to produce a vision of life more spontaneous and real than rule-bound classical cinema.7 In later years, film critics following in Moullet’s footsteps—such as Andrew Sarris, Manny Farber, and Jean-Pierre Coursodon—continued to use “primitive” and the concepts associated with it to describe Fuller’s movies.8 For these critics, Fuller’s stylistic unpredictability is a characteristic worth celebrating and is what links him to primitives in other art forms.

In a related argument, J. Hoberman more recently considered Fuller as a pioneer “abstract sensationalist,” one of several twentieth-century American artists versed in the trashy aesthetic of the tabloids. Hoberman describes the abstract sensationalist as a typically untrained artist who produces sensational work for a mass audience. In particular, he focuses on how abstract sensationalists embrace the tabloid aesthetic of “shock, raw sensation and immediate impact, a prole expression of violent contrasts and blunt, ‘vulgar’ stylization.”9 In championing Fuller as a rough-edged producer of urban, low art, Hoberman highlights the same aesthetic traits seized on by those who have labeled the director a primitive.

However they appropriate or alter the meaning of the term, critics who evoke the primitive to describe Fuller and his work participate in a critical tradition that values an artist’s rejection of classical norms. The longstanding association of the primitive with the instinctual, however, can unfairly characterize artists who produce primitive work as acting without conscious thought or training. As Paul Klee noted, “If my works sometimes produce a primitive impression, this ‘primitiveness’ is explained by my discipline, which consists of reducing everything to a few steps. It is no more than economy; that is the ultimate professional awareness, which is to say the opposite of real primitiveness.”10 In distinguishing between the impression that is created by the final work and the thought that goes into an artist’s working process, Klee rightly cautions against confusing the appearance of simplicity in an artwork with a lack of intention. This caution is particularly appropriate when considering a medium such as film, which requires the coordination of masses of people, equipment, and money. Simply because an artist creates a stripped-down, anticlassical, emotionally raw work does not imply that he or she is working from instinct alone. As subsequent sections of this introduction illustrate, Fuller’s impulses often challenged classical conventions and produced an appearance of spontaneity, yet his working methods and artistic strategies were quite deliberate. Casting Fuller as a primitive simply does not do justice to the complexity and contradictions evident within his work.

In addition to the “primitive” nature of his films, Fuller’s reputation as an independent filmmaker who thrived in the fast-and-loose world of B movies is central to his legendary persona. Fuller’s maverick image arose in the press right as his career stalled in the mid-1960s and has been perpetuated widely ever since. The first in-depth profile of Fuller, a 1965 New York Times Magazine piece titled “Low Budget Movies with POW!” describes his typical film as being shot in ten days on $200,000. Fuller himself is portrayed as a “filmic fireball,” “dedicated to depicting, at rather small cost and in vivid visual terms, the abnormalities of the world around him.”11 This article cemented Fuller’s reputation in the American press as an outsider filmmaker who voluntarily embraced the world of B movies in order to work in opposition to mainstream Hollywood. By the time British and American auteur critics discovered Fuller in the 1960s—as French critics had a decade before—the terms by which his career would be discussed were already in place: he was the primary author of his films, his movies had low budgets, and he worked independent of the grip of Hollywood’s commercial talons.12 These characteristics positioned Fuller as “a role model for maverick filmmakers,” a romantic example of what personal vision and self-sacrifice could achieve.13 The difficulties Fuller faced in getting projects off the ground in his later years only further solidified his outsider persona.

As with the description of Fuller’s work as primitive, his status as a B-movie maverick contains some elements of truth: he often shot on a low budget, and he did have primary creative control over many of his films. Nevertheless, in order to romanticize Fuller’s outsider status, this portrait overlooks the varied production conditions under which he worked and downplays his frequent reliance on Hollywood studios even when he was an independent producer. Throughout his career, Fuller championed the distinctiveness of the auteur voice and struggled to direct his own scripts his own way. In this sense, he was a maverick. But he also recognized that some of the best production circumstances he enjoyed in his five-decade-long career occurred not when he was an independent but while he was working in the studio system.

The dominant aspects of Fuller’s biographical legend have only brought us so far. His years as a journalist, a footsoldier, and a struggling director provide us with a lens through which to view his work, but it is hardly an exhaustive lens. Biography limits us to considering how his life impacted his movies while neglecting other forces that influenced his aesthetic, such as classical norms, industrial trends, and market conditions. The focus on Fuller’s willingness to break classical realist conventions in the criticism of those who describe him as a primitive offers a useful contribution to the study of his films; however, the short articles that dominate this critical strain never explore in a systematic fashion how Fuller’s aesthetic manifests itself through narrative and stylistic choices in individual pictures. Finally, when critics describe Fuller as an independent maverick, their tendency is to portray the studios and their executives as villainous watchdogs who inhibit his creative freedom. This simplistic approach to industry relations fails to consider the variety of needs that bind directors to studios and distributors, as well as the ways these relationships can enable as much as constrain the creativity of directors.

Considering Fuller’s work as a reflection of competing influences enables us to understand more fully the complexities of his films and his evolving strategies as a director. As his career progresses, classical and genre norms, production circumstances, censorship, and industrial conditions shape Fuller’s films to varying degrees, resulting in a body of work that utilizes a range of techniques to express defined artistic interests. Exploring Fuller’s aesthetic vision in the context of his contemporary industrial conditions highlights the most significant aspects of his biographical legend while qualifying and contextualizing longstanding assumptions about his career. A survey of the relationship between Fuller’s narrative and stylistic goals and his working methods further clarifies how he attempted to translate his particular worldview onto the screen.

Fuller as Storyteller

Fuller passionately believed “the story is God,”14 and he fought to film his yarns with minimum interference his entire career. His status as a screenwriter enabled him not only to shoot his own scripts but also to rewrite the work of others, offering him a higher degree of control during preproduction than that enjoyed by many directors of his midlevel stature. Fuller’s screenplays reveal a unique authorial sensibility, one that combines an interest in history and realism with a desire to entertain in an often sensational fashion. In a 1992 self-penned article, “Film Fiction: More Factual Than Facts,” Fuller offers an analysis of the Mervyn LeRoy film I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang (1932) to illustrate how the fictional presentation of an event can appear more “true” than reality: “The more we are Muni [Paul Muni, the actor playing the protagonist], the more the fiction of brutality in the movie becomes factual. Why? Because we are hit with hammer-blows of emotion.”15 These “hammer-blows of emotion” are what Fuller sought to create in his films, crafting his scripts to convey a hard-hitting form of truth through scenes that shock and startle the viewer. This storytelling strategy took hold in Fuller during his career in journalism, was manifested in his films through their narrative content and structure, and was shaped by his screenwriting process.

Fuller himself has confirmed—as several critics suggest—that the tabloid aesthetic and “illustrated lectures” featured in his films are rooted in his years spent in the newspaper business.16 Although Fuller began hawking newspapers on sidewalks in junior high and worked in journalism through the 1930s, his stint as a young crime reporter at the New York Evening Graphic arguably had the greatest impact on his brand of storytelling. A cross between the New York Post and the National Enquirer, the Graphic mixed an impassioned defense of the common man with tawdry stories of sex and violence. There, Fuller learned the art of “creative exaggeration” and the power of a compelling lead, two storytelling techniques that characterize his self-written films.17 As a journalist on the crime beat, Fuller witnessed and then wrote about murderers’ confessions, suicides, executions, and race riots. “Every newspaperman has such a Hellbox to draw from,” he later wrote. “Every newspaperman is a potential filmmaker. All he or she has to do is transfer real emotion to reel emotion and sprinkle with imagination.”18 Fuller’s journalistic career thus provided him not only with strong copy that he could transform into screenplays, but also with an approach to storytelling that de-emphasized exposition and analysis in favor of blunt “truth” and bold-faced, revelatory thrills.

Samuel Fuller in his office while working on Park Row, flanked by statues of Charles Guttenberg (left) and Benjamin Franklin (right) that appear in the film. Ever the newspaperman, Fuller wears a reporter’s visor. Chrisam Films, Inc.

The desire to stretch beyond fact-based reporting led Fuller to begin writing novels and screenplays, yet he retained a tabloid approach to truth-telling throughout his career. His first books published in the 1930s—Burn, Baby, Burn!, the story of a pregnant woman on death row; Test Tube Baby, on artificial insemination; and Make Up and Kiss, an exposé of the cosmetics industry—reveal the topicality and dark humor that infuse the more outrageous of Fuller’s later films. When he began writing screenplays, his goal was “to use the screen as a newspaper.”19 His interest lay in “truthful revelation,” in dramatizing “anything that’s informative and always entertaining.”20 Most significantly, he believed film to be an unrivaled medium in its ability to educate as well as entertain:

One day the greatest educational medium will be the film. Millions of children will watch a moment in history told through drama so gripping that dates of events will become dates of exciting moments, instead of numbers to crowd their reluctant minds…. There is no art medium that can accomplish this and reach as many people as the art of film.21

Such quotes have led some critics to suggest that Fuller’s scripts reveal a definite ideological agenda.22 To be sure, Fuller does not balk at revealing the failings of American society, and his films repeatedly engage race and gender in a frank and uncompromising manner rare for their times. Yet Fuller’s contradictory narratives defy coherent political analysis, leading him to be described in the press as everything from a liberal to a fascist to an anarchist. While he may intend to educate, the “creative exaggeration” Fuller employs in the storytelling process results in films that agitate the viewer, physically, intellectually, and emotionally, rather than offering a clear political position.

Fuller’s storytelling goal is to arouse emotion, and his screenplays combine hard-boiled characters, ironic contradictions, excessive conflict, and a selective embrace of classical and generic conventions in order to shake the viewer up. Fuller called his characters “gutter people,” outcasts who lived by their own code in a shadowy world he found more inherently dramatic than that occupied by clean-cut, well-behaved Americans.23 In their own lingo, they are “retreads,” “doggies,” “cannons,” “grifters,” “wetnoses,” “ichibons,” and “bon bons.” Typically criminals (I Shot Jesse James, The Baron of Arizona, Pickup on South Street, Underworld, U.S.A., The Naked Kiss, Shark!, Thieves After Dark), misfits (The Steel Helmet, Fixed Bayonets, Hell and High Water, Run of the Arrow, The Big Red One, Street of No Return), or obsessives (Park Row, Forty Guns, Shock Corridor, White Dog), Fuller’s protagonists lie, cheat, steal, betray, or kill in order to achieve their desires. For them, the ultimate triumph is merely survival. While Fuller draws from stock “underworld” types—thieves, prostitutes, cops, and reporters—he uses them to reveal the bitter ironies of life. He shows us an American footsoldier shooting a POW, a pickpocket laughing at patriotism, politicians in bed with criminals, children learning to become terrorists—the veneer of polite society and civilization stripped away to expose the shocking truth.

Fuller’s narratives place his protagonists in extreme situations fraught with conflict and contradiction in order to produce “emotional violence.” Fuller’s favorite example of an emotionally violent film was David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945), a bittersweet romance about two people who fall in love but are married to others:

Now when you have a married man and a married woman, they’re gonna cheat. They’re all scared, scared, scared. But these two won’t even touch hands on a bed; they’ve never kissed. The guilt! They’re guilty, and they haven’t done a damn thing—but in a way they have. And the violence is against themselves. That’s better than any barroom stuff.24

At first, this may seem a strange example for Fuller to embrace, given the vast tonal and stylistic differences between his pictures and the comparatively restrained Brief Encounter. Yet what Fuller responds to in this film is the inner conflict of the two protagonists: they want to respect their marriages, but they also want each other. Fuller equates emotional violence with the severe psychological turmoil that results from an individual having two opposing desires that cannot both be satisfactorily fulfilled. This is the sort of narrative situation that most frequently confronts his protagonists, from I Shot Jesse James’s John Ford, who believes he has to kill his friend in order to marry his girl, to The Naked Kiss’s Kathy, who desperately wants to marry the town millionaire and lead a clean life but discovers that the millionaire is a sexual predator and clean living is dirtier than she thought. Fuller’s embrace of paradox often results in irony, a bitter recognition of truth’s complexity.

Fuller’s interest in creating intensified narrative situations in his screenplays often overrides the powerful influence of classical conventions. Classical Hollywood narratives tend to feature tightly woven chains of cause and effect; each scene leads directly into the next, with no additional scenes that are extraneous to the dominant narrative action.25 These norms help to ensure consistency, coherence, and verisimilitude within screenplays—qualities Fuller was often willing to sacrifice in order to achieve heightened conflict. Fuller’s original scripts sport looser, more episodic structures designed to contrast the rhythms and tones of scenes and to unsettle audience assumptions. Action may arise quickly—and with little apparent motivation—and be followed by another unexpected event. The narratives of some of his movies, such as Park Row, Forty Guns, Shock Corridor, Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street, The Big Red One, and Street of No Return, even appear overstuffed, as if Fuller thought of too many great plot points and simply decided to keep them all. Sharply contrasting action, sudden shifts in tone, surprising plot developments, and multiple lines of conflict all contribute to creating intensified narrative situations in Fuller’s films, even as they often undercut viewer expectations of clear causal links, consistent character psychology, and careful plot motivation. It is telling that film trade publications described the vast majority of Fuller’s pre-1970s pictures as melodramas, applying a longstanding definition that associated the term with thrilling, action-packed stories.26 This trend is a potent reminder that Fuller’s work is a variant of a cinematic tradition that extends back to the serials of the silent era, in which coincidental, implausible, and often confusing narratives function to create heightened emotion and sensationalism.27

While reference to genre conventions helps to motivate many of Fuller’s narratives, his films just as often challenge our generic expectations. With a few exceptions, Fuller’s movies participate in the war, crime, and western genres—standard territory for low-budget action films.28 Genre films contain highly conventionalized protagonists, settings, situations, themes, and iconography; while variations on each element occur, their repetition over the course of a genre’s development shapes viewer expectations regarding what is “appropriate” for the genre. Although Fuller’s genre films often employ conventional character types and situations, they tend to twist some genre elements and completely ignore others, even while relying on genre to motivate unexplained action. Rather than using genre to explore a defined cultural conflict—in the western, for example, the way of the gun vs. the rule of law—Fuller selectively invokes generic elements in his films as a foundation for his own narrative interests. Fuller’s preferences for brutish characters and heightened conflict lend themselves easily to some genres, such as crime and war; his westerns and social problem pictures, however, are less conventional and often contain narrative structures and plot elements not usually found within the given genre. After Fuller started his own production company in the late 1950s, his use of excessive sex and violence further warped his genre narratives, and several of his subsequent films are primarily structured around sensational set pieces (Shock Corridor, The Naked Kiss, White Dog, and Street of No Return). Genre conventions thus provide a convenient structure on which Fuller can build his own ideas; some structures are strengthened by his fresh approach, while others buckle under the weight of his distinct worldview.

Fuller’s preproduction drawing of the character Short Round from The Steel Helmet. Chrisam Films, Inc.

Fuller’s writing process enabled him to visualize the development of his screenplays and to orchestrate narrative elements for maximum emotional impact. His scriptwriting involved copious research and detailed planning. An early profile of Fuller written at the beginning of his tenure at Twentieth Century–Fox describes how he initially developed a story by drawing pictures of characters, locations, and key action before sitting down at a typewriter.29 Later interviews suggest this process could also be contemporaneous with the actual writing of the screenplay but confirm Fuller’s tendency to cast actors according to his character sketches. He also produced drawings of sets that functioned as blueprints for the art department and drafted upwards of seventy-five drawings detailing how scenes should be shot.30 Fuller’s penchant for visualizing his stories as he was writing them harkens back to his years in journalism, when he often picked up extra cash from drawing cartoons; more significant, however, is how this process underscores his tendency to think in pictures, to imagine how a story can be told through visually arresting images.

When working on several scripts at a time, Fuller also used a system that enabled him to keep track of the narrative structure of each project on a blackboard. The blackboard for each script contained a chart of the film’s plot, with white chalk indicating exposition, yellow chalk for the introduction of a character, blue chalk for romantic scenes, and red chalk for action and violence.31

If I can end the first act with one or two red lines, the second act with two or three red lines, and the third act with four or five red lines, I am going uphill. So I can get a pretty good idea of the balance of the violence and of the romance or anything I want on that board.32

While Fuller admits he did not use the blackboard to map out every script, profiles and interviews suggest he continued to strive for a high degree of preparation and careful plotting of scripts in order to develop contrasting emotion and accelerating action. As Fuller’s screenwriting process favored heightening dramatic conflict and varying the tones of scenes over producing a tight, three-act, causal narrative, it is little wonder that the norms of verisimilitude, clarity, and coherence embraced by classical Hollywood filmmaking are not always apparent in his movies.

Samuel Fuller considered himself first and foremost a storyteller, and the way he told stories on film reflected how his narrative preferences were filtered through cinematic conventions and industrial pressures. While his early scripts produced by Lippert and Twentieth Century–Fox reveal closer adherence to classical and generic norms, Fuller’s move into independent moviemaking in the late 1950s enabled him to film scripts that had previously been rejected as too unconventional. In the process of establishing his identity as an independent and targeting an adult audience, Fuller’s stories became increasingly sensational, topical, and sometimes less than tasteful. Throughout his career, his narratives put to work the lessons he learned from his years in journalism and demonstrate a willingness to flaunt custom and propriety in order to create challenging, startling viewing experiences. At their best, his narratives are exercises in arousal, a surprising blend of brutality, humor, and pathos. The shocking thrills contained in Fuller’s scripts are amplified onscreen by his production methods. A review of his visual style provides a helpful introduction to the strategies he used to bring his punchy yarns to two-fisted life.

Movement and Conflict

During the studio era, Hollywood operated according to a mode of production that encouraged speed, efficiency, and original approaches to classical conventions. Fuller’s early track record of shooting fast, spending little, and delivering genre hits made him an attractive find for Darryl Zanuck and the other studio executives who courted him in the early 1950s, but Fuller never fully embraced the “invisible” style of directors like George Cukor and Howard Hawks that dominated Hollywood in the studio era. According to the Fuller legend, the characteristics that constitute classicism—balance, order, and unity—should not even be included in a sentence bearing the name of Samuel Fuller. While Fuller’s films do frequently appear unbalanced, incongruous, and disunified, they are not so all of the time. In fact, Fuller was entirely capable of adhering to classical norms, and many of his films, particularly those produced by Twentieth Century–Fox, contain scenes that are models of conventional staging and editing. Any argument concerning Fuller’s visual style must acknowledge the complete range of its expression, taking into account both the traditional and the weird, what worked within the studio system and what changed without.

Although Fuller’s films may often appear haphazard or unstructured, their visual style is less the result of negligence, instinct, or limited production resources than of a number of conscious strategies designed to maximize the visceral impact of the viewing experience. Fuller’s work is shaped by his tendency to shoot long takes as the primary foundation of scenes; to juxtapose long-take scenes with those reliant on montage; and to develop kineticism, sharp contrasts in tone and style, rhythmic and graphic editing patterns, and stylistic “weirdness.” Fuller’s dominant stylistic strategies complement and support each other, distinguishing his films from those made by directors who worked with similar resources in like genres. While not all of these characteristics are contained within every Fuller film, and they are manifested through different techniques in different films, even the most classically constructed of Fuller’s pictures contain at least two of these general strategies. In conjunction with the narrative, these tactics are designed to startle the audience and produce the “hammer-blows of emotion” that Fuller so desired.

Few production and postproduction records survive for Fuller’s films, yet interviews with him and his crew members, as well as the films themselves, provide some indication of how Fuller’s working methods contributed to the creation of visceral effects. While his production periods were often quite short, Fuller made time for rehearsal before shooting even on his low-budget pictures, suggesting that the intense planning he put into preproduction carried over onto the set.33 What most distinguished Fuller’s approach to filmmaking were his ideas concerning how a scene should be shot. Classical Hollywood filmmaking typically strives to maintain continuity in space, time, and action in an effort to communicate the narrative clearly and efficiently. A conventional scene might begin with a wide master shot to establish the space, then cut in to a medium shot or two-shot that isolates significant action, then subsequently cut into close-ups or shot–reverse shot patterns that highlight character reactions and emotions, and finally cut back out to a medium or wide shot to re-establish the space as a new line of narrative action is initiated. This type of editing pattern, often described as analytical editing, presents the totality of the space and then breaks it into parts, firmly directing the viewer’s gaze to ensure clear and efficient exposition of the narrative.34 In order to provide coverage for a scene—or enough camera angles and compositions for editors to choose from—a director customarily films the complete scene once in the establishing master shot, then shoots sections of the scene again from closer angles and shot scales. While Fuller embraced the concept of a master shot, the general lack of analytical editing and coverage in most of his films, particularly those made outside of Twentieth Century–Fox, suggests that for him, the master shot functions less as an opportunity to establish the space than as the very foundation of the scene. Rather than acting as a jumping-off point for shot–reverse shot or point-of-view shot patterns, the master often becomes the dominant shot for scenes in Fuller’s films, intercut with only a few quick close-ups or cutaways.

Fuller’s tendency to favor the master shot was rooted less in a desire for economy than in a desire to exploit the tension produced by the technical requirements of a long take. “I don’t like to shoot a scene from a close angle, medium, long shot, and then take it into the editor and see if we can do anything with it,” he said. “I want to see the excitement on the set, while we’re shooting.”35 Joseph Biroc, Fuller’s director of photography on Run of the Arrow, China Gate, Forty Guns, and Verboten! also pointed out that by forcing the actors to perform a scene in one extended take, Fuller was able to capitalize on their nervous energy, as well as on unexpected reactions or bits of business. “Sam felt—and he was right—that the longer you make the shot, the better the people can act it out, the more real it all seems, instead of making it in small pieces—cut, cut, cut, the way it is usually done.”36 As the master-shot long take requires cast and crew to focus their attention and be “in” the scene for a longer period of time, it increases the potential for unexpected interactions between actors that might speak to the narrative within the scene.

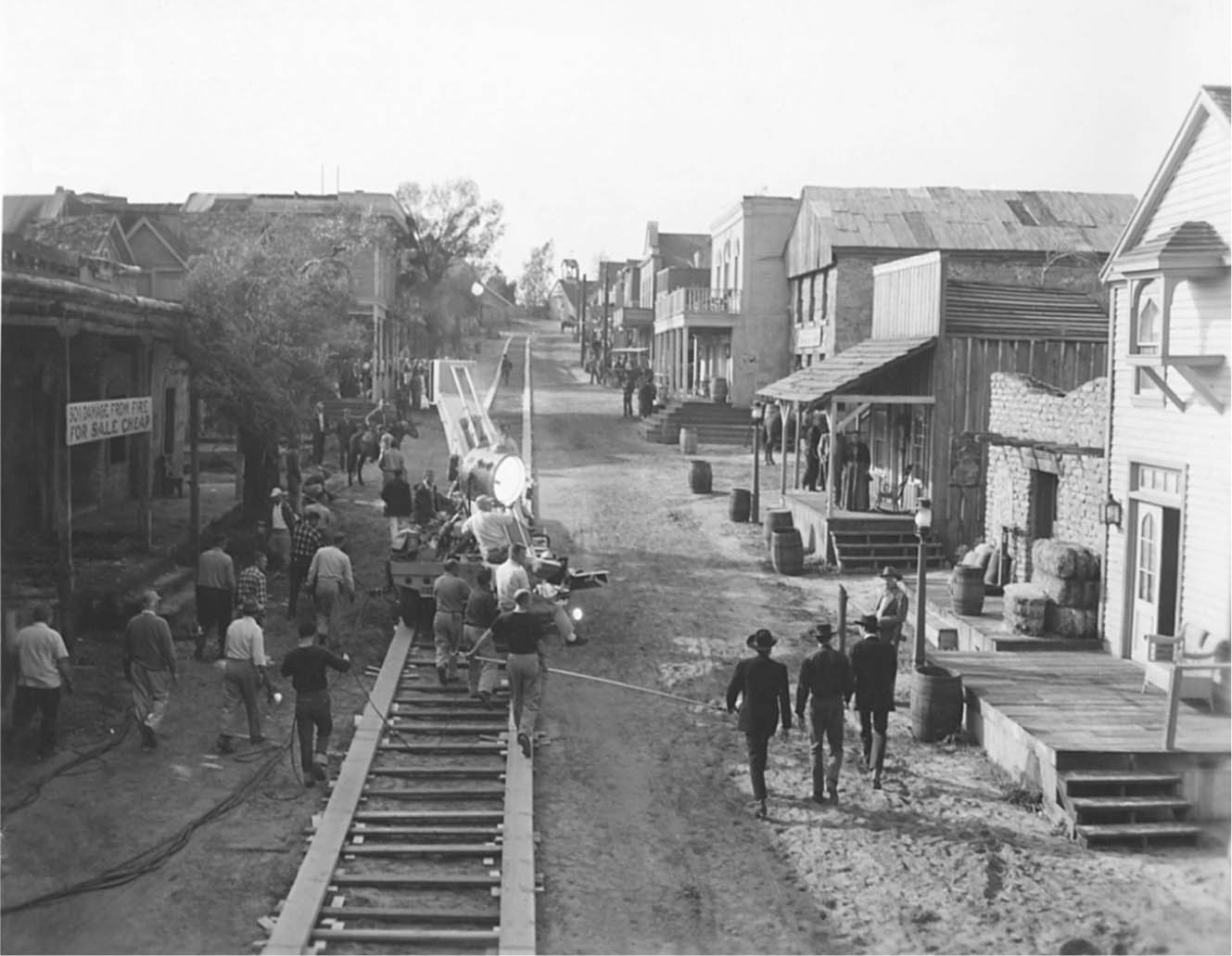

Fuller laid extraordinarily long tracks during the production of Forty Guns—the length of Twentieth Century–Fox’s back lot—in order to film the characters of Griff, Wes, and Chico walking down Main Street in one continuous shot. Extended tracking during master-shot long takes is part of Fuller’s stylistic signature. Chrisam Films, Inc.

When combined with his tendency to shoot only one or two takes for each shot, Fuller’s preference for the master-shot long take often resulted in a lack of coverage for scenes that troubled his editors and challenged their ability to “fix” continuity breaks. Yet these “mistakes” appear to have concerned Fuller little, as they often contribute to his preferred stylistic strategies. Gene Fowler, Jr., Fuller’s editor on Run of the Arrow, China Gate, and Forty Guns, explained:

Sam is a guy who shoots very long scenes, no cuts, and usually shoots just one take. So if anything turned out to be wrong with the take you were screwed.… If an actor would flub a line in the middle of a take it presented quite a problem for me because you had nothing to cut away to.37

An advantage to shooting a scene from multiple angles and shot scales is that adequate coverage enables the editor to use a different shot of the same action if there is a problem with dialogue, acting, lighting, sound, cinematography, etc. However, if no other shot of the action exists, the editor must either leave the error in the shot or create an unconventional way to mask the error. Fowler and Fuller’s other editors thus frequently resorted to cutaways to contiguous but irrelevant spaces or alternate takes of the same master shot to cover technical problems. While these solutions might effectively mask the mistake, they can glaringly violate the continuity of the diegetic world—the world of the film’s story.

Fuller’s editors also used close-ups and optical process shots to create visual variety in scenes recorded primarily in one long take with little or no camera movement. Static long takes could significantly slow the pace of a scene and offer fewer means of directing the viewer’s attention to important narrative information. One strategy seen over and over again in Fuller’s films is the use of the close-up and optically processed blow-up or zoom to vary the scale of the image and emphasize significant emotional moments. Gene Fowler, Jr., explained in an interview how he worked with Twentieth Century–Fox’s optical department to produce a zoom that looked like a dolly in postproduction in order that he might have the freedom to move into a close-up and back out to a long shot during extended single takes in China Gate.38 Optical process shots are also used in I Shot Jesse James, Park Row, Run of the Arrow, The Crimson Kimono, Underworld, U.S.A., and Verboten! While optically processed close-ups and zooms draw attention to themselves due to a slight increase in the grain of the image, they enabled Fuller and his editors to stretch the expressive boundaries of the master-shot long take in the absence of character blocking and camera movement.

Fuller’s preference for shooting master-shot long takes rather than complete coverage was not unique in postwar Hollywood filmmaking. The films of directors such as Vincente Minnelli and Otto Preminger typically display much greater average shot lengths than those of Fuller, as they contain more scenes shot in one long take and a generally more uniform use of the long take throughout. Fuller, on the other hand, only produced two pictures with average shot lengths in excess of the era’s norm: Park Row and House of Bamboo.39 While Fuller often uses the master shot as the foundation of a scene, the editing strategies discussed above, as well as the juxtaposition of long takes with heavily edited scenes, tend to reduce the average shot length of his films. What makes Fuller’s interest in shooting with little coverage and few takes notable is how it contributes to his dominant stylistic strategies. Long takes with rapid camera movement heighten the kineticism of scenes; when juxtaposed with a montage sequence, long takes can produce startling shifts in tone; and master shots intercut with close-ups, optical process shots, or extraneous footage can disorient the viewer.

In addition to staging scenes around long-take master shots, Fuller also builds more heavily edited sequences around quick takes of medium shots and close-ups. Fuller’s montage-based scenes typically employ constructive editing. Instead of cutting into a detail from a wide master shot as is common in analytical editing, constructive editing eliminates establishing shots and suggests space through the juxtaposition of images. Movement and screen direction connect action from one shot to the next. The viewer then constructs the entire action mentally by uniting the parts of the action seen in separate shots. Fuller frequently draws on constructive editing to suggest spatial relations through eyeline matches—when the shot of a character’s glance is juxtaposed with a shot of the object that is being seen—as in the openings of I Shot Jesse James and Pickup on South Street. He also utilizes constructive editing for more explosive purposes, repeating a series of compositions multiple times to create a percussive rhythm.

One memorable example of constructive editing in Underworld, U.S.A. illustrates how this technique contributes to Fuller’s desired emotional effects. Gus, an assassin, has been ordered to kill the daughter of a crime witness, so he runs the girl over with his car while she is out riding her bike. The scene is organized through ellipses, as medium shots of the girl’s head and shoulders on the bike, Gus’s head and shoulders in the car, the girl’s legs and bike wheel, and Gus’s car wheel are intercut ever more rapidly to suggest her pursuit. Increasingly tighter shots of the girl’s mother in the window watching her daughter’s race for life occasionally interrupt the chase, until the mother screams and closes her eyes. The last shot shows the girl sprawled on the concrete with her mangled bike beside her, the victim of a moment of impact the viewer is led to imagine but never actually sees. The rhythm and pacing of the editing in the scene, as well as the need for viewers to link the shots together mentally, heighten our visceral response and multiply our horror.

One of the most distinctive aspects of Fuller’s aesthetic signature is his propensity for “weirdness.” This was actually a technical term for him. As he tells Jim Jarmusch in the documentary Tigrero: A Film That Was Never Made (1994), any time his cameraman or assistant director came across a “W” in the margin of the script, he knew to ask Fuller what to do. The “W” stood for weirdness: an aggressive disregard for classical conventions governing the presentation of space, time, and movement. Weirdness creeps into Fuller’s pictures beginning in the Globe era and escalates from there, appearing most frequently—but not exclusively—during subjective sequences. Even relatively stylistically tame sequences can be defined as weird if narrative and stylistic logic fly out the window. Explosions of weirdness are one of the defining aspects of what makes a film a Fuller.

Frame enlargements of the final shots from a murder sequence in Underworld, U.S.A. joined together via constructive editing. Constructive editing relies on the viewer to piece together the spatial relationships between each shot. This technique was often used by Fuller to involve the viewer in acts of extreme violence.

Because the visceral effects Fuller sought could be realized in a swift and inexpensive manner—as they relied on a minimum of camera setups and necessitated only the most basic production design—his stylistic preferences were not entirely out of step with the efficiency championed by the classical system. By adapting his interest in conflict and kineticism to the available resources and production circumstances of each film, Fuller could produce original storytelling in an expedient manner, thereby helping to make his stylistically unusual films more acceptable to the studios and major distributors. Nevertheless, his willingness to draw attention to stylistic choices in a manner not widely embraced in Hollywood made Fuller’s visual style somewhat problematic, especially when exercised in less action-oriented genres that do not inherently strive to shake up the viewer. The varied expression of Fuller’s stylistic preferences reflects his journey into and out of big-budget studio productions in the mid-1950s, his heightened creative control after becoming an independent producer, his progression toward increasing sensationalism, and the eclectic experimentation of his final films.

All too often critics highlight the rough, occasionally crude construction of Fuller’s work and its various excesses without fully considering the range of his aesthetic choices and their intended effect on the viewer. Luc Moullet’s attitude toward Fuller typifies that of many who consider him a “primitive” genius: “Perhaps no other director has ever gone so far in the art of throwing a film together. Whatever the extent of his negligence, one cannot but be fascinated by the spontaneity it brings with it.”40 Yet as we have seen, Fuller was hardly one to “throw a film together.” His working process was detailed and deliberate, and he was consistently disposed toward narrative and stylistic strategies that aroused and provoked the viewer. The following chapters describe how production conditions, studio and regulatory oversight, and market trends shape the articulation of Fuller’s artistic impulses, beginning with his early years at the low-budget studio Lippert Productions. While his first two pictures flirt with unconventional narrative and stylistic choices, in-depth analysis of The Steel Helmet reveals the blossoming of Fuller’s personal aesthetic and its roots in movement and conflict.