CHAPTER FOUR

The Freelance Years, 1961–1964

After the collapse of Globe Enterprises, Fuller continued the rest of his career as a writer/director for hire. Rather than making a new financing and distribution deal himself or a slate of films as an independent producer, Fuller now primarily relied on other producers to come to him with an offer for financing. Given the spotty box-office returns of his last few films for Globe, such an offer could be perceived by a producer as a risk, unless the project particularly suited Fuller’s talents or was developed so inexpensively that little risk was involved. At the same time, Fuller was selective about joining projects already in development, while he had little ability to pick and choose producers for his own original scripts. Combined with the continued decline of the programmer, the net result for Fuller was a production slow-down.

Although Merrill’s Marauders, Fuller’s first gig as a freelance director, returned him to the world of big-budget action films he experienced at Twentieth Century–Fox, for the rest of the decade he scraped together work in television and in very low-budget filmmaking. After finishing Merrill’s Marauders in 1962, he wrote and directed an episode of the popular television western The Virginian and directed an hour-long story about a troubleshooter for the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare that aired on The Dick Powell Show. The following year he made a deal with Fromkess & Firks Productions, Inc. to write, direct, and produce two pictures to be distributed by Allied Artists, negotiating an advance plus a third of the net profits of each film.1 Leon Fromkess, a former vice president of Samuel Goldwyn Productions, included the two films as part of a five-picture contract he and Sam Firks signed in November 1962 with Allied.2 Founded in 1946 as a subsidiary of Monogram to handle the production and distribution of higher-budget films, by the early 1960s Allied Artists relied largely on independent producers for its often inexpensive product. The Fromkess-Firks deal threw Fuller back into the sort of low-budget filmmaking that he initiated his career with at Lippert, but now Fuller began producing a slightly different kind of movie, one grounded less in genre and more in sensation and controversy. While neither Shock Corridor nor The Naked Kiss attempt in any way to reach out to the youth market, they fall closer to the exploitation category than any other films in Fuller’s career, pushing topical buttons and playing with taboos in a fashion that bordered on tasteless—and sometimes crossed the line. Blunt gut punches with heavy social overtones, they remain among Fuller’s most audacious and unsettling films.

Return to War: Merrill’s Marauders

While Fuller was editing Underworld, U.S.A., he accepted an offer from independent producer Milton Sperling to direct Merrill’s Marauders, the true story of the deadly march made by Brigadier General Frank Merrill and his men behind enemy lines in Burma during World War II. Fuller initially resisted Sperling’s call to direct, intent as he was on completing for Warner Bros. his own World War II story, The Big Red One, but Jack Warner encouraged Fuller to view Merrill’s story as a “dry run” for his own film.3 Sperling had been working on the Merrill project since 1959, when he purchased the screen rights to The Marauders, an autobiography written by one of Merrill’s lieutenants, Charlton Ogburn, Jr.4 Two screenwriters had already taken a shot at the adaptation by the time Fuller and Sperling began scouting locations in the Philippines at the end of November 1960; Fuller himself completed a draft upon their return, and the final writing credit was shared by him and Sperling.5 Cooperation from the Department of Defense and the U.S. Army Special Forces enabled the production to be based at Clark Air Base in the Philippines and to enjoy housing, vehicles, equipment, and communications at no cost, while the Philippine Army provided twelve hundred soldiers for four days of work doubling as Japanese. Sperling crowed to studio chief Jack Warner that the production budget of only slightly over $1 million was a fraction of what the Technicolor and CinemaScope feature would have cost without military assistance.6 Production commenced in March 1961 for a planned forty-one day shoot around Clark, the jungles of Luzon, and the Pampagna mountains; within a week rain began to slow the picture, forcing Fuller to improvise material when locations could not be reached and eventually to cut scenes entirely. Though the production ended six days over schedule, both Sperling and Warner praised Fuller’s effort. In a letter to Warner, Sperling described Fuller as “a tough, knowledgeable man with a no-nonsense attitude about picture making,” to which the studio head replied, “Sam Fuller is a gutty guy and that’s why he is where he is. We can use more guys with blood, sweat, guts, tits, and sand!”7

Merrill’s Marauders depicts the legendary efforts of the American 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) in Burma in 1942. Led by Brigadier General Frank Merrill (Jeff Chandler), the footsoldiers—all volunteers with two years’ experience in jungle warfare—are ordered behind enemy lines to prevent the unification of German and Japanese forces in India. The film picks up the unit on its way to Walawbum to destroy the main Japanese supply base. Already exhausted, the men look forward to relief by the British. After capturing Walawbum, however, Merrill receives orders to take out the railhead at Shaduzup and then cross the mountains to assist the British at Myitkyina, the Japanese gatehead to India. Knowing his men are already hungry, tired, and ravaged by disease, Merrill accepts they must do the impossible—survive a five-hundred-mile journey and still have the strength to defeat the enemy. Lieutenant Lee Stockton (Ty Hardin), the head of Merrill’s point platoon and his surrogate son, reluctantly supports the decision, though Merrill only reveals to him the initial goal: Shaduzup. The men slog through swamps and rivers to the railhead, where the battle disintegrates into chaos and confusion. With the living now as inert as the dead, the unit’s doctor declares them unfit to continue, suffering as they are from an “accumulation of everything.” Merrill ignores him and decides to continue to Myitkyina, announcing: “When you’re at the end of your rope, all you’ve got to do is make one foot move in front of the other.” Upon hearing the orders, Stockton resists sending his men into certain death and requests permission to be released from command. Merrill denies his request, and the unit heads out into the mountains, ground down by exhaustion. After defending the initial attack by the Japanese outside of Myitkyina, Merrill realizes they must advance into Myitkyina itself. Exhorting his spent unit to stand and fight, Merrill suffers a heart attack, and Stockton rallies to take his place. Against all odds, the men march out; narration reveals their success at Myitkyina and the eventual toll: of the three thousand soldiers who began the journey, only one hundred remained in action.

The military support that Sperling wrangled for the picture brings new levels of authenticity to Fuller’s depiction of war. Unlike The Steel Helmet, Fixed Bayonets, and China Gate, Merrill’s Marauders was shot entirely on location in areas that could actually pass for central Asia (i.e., not in a studio, Griffith Park, or Columbia’s ranch). For the first time we track with the soldiers through actual swamps and across a real mountainside, making their physical experience that much more palpable. Additionally, the cooperation of the American and Philippine armies enabled Fuller to work with extras that not only had military training but also could reasonably replicate the thousands of soldiers involved in Merrill’s engagements. No longer did twenty extras have to stand in for two hundred, and Fuller’s extreme wide shots during the battles allow the viewer to register the different waves of enemy attack and the overwhelming odds facing the Marauders. Access to military ordinance further heightens the intensity of the battles, freeing Fuller from relying on stock footage to suggest an artillery barrage; explosive devices in Merrill’s Marauders fall loud, fast, and frequently, increasing the nerve-wracking impact of the combat scenes.

With its emphasis on narrative clarity and cohesion, the script for Merrill’s Marauders also reflects the influence of Sperling on Fuller’s storytelling and recalls the tight plots of his Twentieth Century–Fox years. From the opening narration, which uses stock footage and maps to carefully contextualize the struggle for Burma and purpose of Merrill’s mission, to the constant discussion amongst the officers of where they are and what shape the men are in, to the animated maps that illustrate each stage in the journey, each element within the narrative works in a redundant fashion to clarify the action. The digressive episodes that allowed for didactic conversation and colorfully individuated characterization in China Gate, The Steel Helmet, and even to an extent in Fixed Bayonets are largely absent in Merrill’s Marauders. Politics plays no role in the soldiers’ motives or actions, and only Merrill and Stockton receive any kind of back-story. The intimacy of the platoons that formed the basis of Fuller’s previous war pictures is here replaced by the broader strokes necessitated by following large-scale troop movement, and dialogue overall is kept to a minimum.

Though Merrill’s Marauders is more streamlined than Fuller’s previous combat pictures, it maintains his investment in depicting the absurd ironies, tangled emotions, and mind-numbing exhaustion experienced by soldiers during war. Once again, a delightfully dedicated mule driver is part of the unit, poignantly dying as he carries the load his animal was too exhausted to support. And harkening back to the influence of Short Round on Zack in The Steel Helmet, Merrill’s men find themselves touched by simple human kindness in the midst of the horror of war. After the battle at Shaduzup, local villagers bring the drained soldiers bowls of rice and water, an act of wordless generosity that reduces a tough sergeant to tears. As ever, Fuller’s footsoldiers remain obsessed with sleep, food, and personal health, but the overall physical toll of warfare achieves new emphasis in Merrill’s Marauders. The tedium and strain of marching are broken only by brief rest and the chaos of battle. Over and over, the soldiers discuss their overwhelming desire to see the conclusion of their mission, but the mission just keeps being extended—at the end of the movie, we leave the men still marching. Though the narrator triumphantly announces the unit’s eventual success at Myitkyina, what we take away is our memory of what we have seen—not a successful mission accomplished, but a mission that never ends.

Fuller (lower left, in white shirt and baseball cap, with cigar) and his crew get wet during the production of Merrill’s Marauders. Shot in CinemaScope on location in the Philippines, the film exploits the widescreen frame to show long lines of weary men marching through the jungle. Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

The fight at the Shaduzup railhead most fully embodies Fuller’s vision of the nightmare of warfare. The sequence begins with a series of static shots of the tracks, trains, and oil tanks of the depot, all devoid of men. No clear visual connection links the shots together, making ambiguous the arrangement of space. Suddenly, the Americans and Japanese converge, and Stockton’s platoon hunkers down among a maze of hulking concrete blocks. The blocks create a confusing series of alleys and blind spots, and a rapid montage depicts American and Japanese soldiers running and shooting in every direction. First an American soldier will enter a corridor and be shot; then a Japanese soldier will enter the same corridor in the same area and also be shot. The editing follows no clear action-reaction pattern, and the opposing forces hold no delineated geographic position; as a result, the viewer is often unsure of the national identity of the soldiers, who their targets are, and who is shooting at them—all that is clear is that some soldiers are shooting, and others are falling to the ground. The lack of consistent screen direction and spatial continuity leaves the viewer, like the soldiers, grasping for an understanding of what is going on. We think we see an American shooting another American. Is that what we saw? The action develops so quickly we can’t be sure. Finally, a high-angle shot provides an overview of the battle, revealing circles of the blocks arranged like the petals of a daisy, one after the other, shielding men firing at all angles. The impression is of men cornered, unclear of their position and shooting wildly at anything that moves. This is the lesson Fuller tries to impart: war is chaotic, and desperate men do what is necessary to survive. At battle’s end, a crane follows Stockton, traversing 180 degrees, as he steps from block to block high in the air, surveying the scene. His is the only movement within the frame, around him only anonymous bodies. The full weight of what it means to be an officer, to order men into battle, falls on his shoulders. Fuller closes the scene as he opens it, with high-angle static shots of the railyard, now carpeted with the dead—an unsettling vision of war’s toll, a vision that complicates what it means to “win.”

The contradictory nature of leadership in war—a theme Fuller first explored in Fixed Bayonets—is at the heart of Merrill’s Marauders and is vividly expressed through the characters of Stockton and Merrill. Exposition early in the narrative characterizes the relationship between the two as that of adopted son and father, one a designated successor to the other. Merrill oversaw Stockton’s unit during the previous Burma incursion in 1940, and when the young soldier was wounded but had no family to notify, Merrill wrote about him to his own wife, including a photo of his protégé. Merrill’s confidence in Stockton is summed up in his exclamation to his friend, Doc: “Some day that boy’s gonna be a general!” But Stockton finds it difficult to distance himself from the soldiers he leads—soldiers he once fought beside as an equal. He suffers every time he receives a dead soldier’s dog tags and struggles to write the necessary letter to the deceased’s family. A telling shot at Walawbum encapsulates Stockton’s predicament: Merrill has just told Stockton of the mission to Shaduzup (“Think you can stand losing more of your friends?”), and now Stockton must tell his platoon. Over the shoulders of Merrill and Doc in the foreground left, we see Stockton in the far right distance relaying the news; wordlessly, the men swarm past Stockton until he is alone in the field, and Merrill turns grimly away. Command has isolated Stockton from his platoon, and Merrill knows it is he who has brought this to bear. The distance between the two within the frame suggests the difference in their years—Merrill, at the end of his career as a leader, Stockton at the beginning—but Merrill’s keen attention to his lieutenant’s struggle reminds us that he shares it, too. Stockton may be sending a platoon out to die, but Merrill is sending all three thousand men. As he later reminds Stockton, “When you lead, you have to hurt people—the enemy and sometimes your own.” The ugly paradox of command—that ordering an attack on the enemy means ordering the death of your own men—is highlighted in a poignant shot after the battle at Shaduzup, once Merrill has told Doc that he will force the unit on to Myitkyina regardless of their lack of fitness. The composition frames Doc in the far left distance, Merrill in the far right distance, and in the foreground center is the medic, attending to a stream of dying and wounded men. Our eyes are drawn to the injured soldiers, the moral burden that Merrill carries, the weight that divides him from even Doc, his closest friend. This is the weight that Denno so feared to carry in Fixed Bayonets.

At the end of the film, when Merrill goes from one collapsed soldier to the next, kicking their boots and exhorting them to follow him and continue to fight, one cannot help but think back to Fuller’s story of his own experience on D-day. Pinned down on Omaha Beach with an exit just blown open, Fuller saw his own commander, Colonel George A. Taylor, stand up amidst the German barrage and yell, “There are two kinds of men out here! The dead! And those about to die! So let’s get the hell off this beach and at least die inland!” Then Taylor kicked and swore at his understandably cowering men until they got their asses off the ground and ran behind him, through the bullets and to the breach.8 Fuller later memorialized this moment in The Big Red One, but the ending of Merrill’s Marauders was, as Jack Warner predicted, a dry run—an opportunity to acknowledge the experience of the infantry shared between soldiers. When Stockton takes Merrill’s place and prods his men to rise and fight, he is no hero, but a man with a job: to do the impossible, to survive, and to try to live with himself afterwards.

Released by Warner Bros. in Los Angeles over Memorial Day weekend and throughout the country in a large-scale rollout from June through August 1962, Merrill’s Marauders garnered Fuller glowing reviews in national publications as well as in the trades.9 Boxoffice notes that the film’s ninety-eight-minute running time allows it to be shown easily as either a first or second feature, but it headlined or ran solo in downtown and neighborhood theaters both during its initial outing and re-release the following year.10 Variety reported the film’s rentals—the amount of money collected by the distributor after theaters receive their share of the box-office gross—to be $1.5 million, ranking the picture fifty-first for the year and likely to break even or be profitable.11 Merrill’s Marauders once again demonstrated Fuller’s ability to make unique yet crowd-pleasing big pictures when provided with the resources. After production on the film was complete, Fuller expected to return to Columbia to make the third film of his deal—reportedly either Powder Keg, Cain and Abel, or Pearl Harbor—but Columbia financed and distributed no additional pictures from Globe.12 Fuller’s career as a freelance filmmaker would continue.

Adult Exploitation: Shock Corridor and The Naked Kiss

Shock Corridor, the first of Fuller’s two pictures for Fromkess-Firks, is an astonishing provocation. Inspired by the story of Nellie Bly, a journalist who in 1887 posed as a patient in order to write an exposé of the Blackwell’s Island mental hospital, Shock Corridor concerns Johnny Barrett, an ambitious reporter who angles to be admitted to a psychiatric institution in order to solve the murder of an inmate named Sloan and win the Pulitzer Prize. The first film Fuller made with Stanley Cortez, the much-lauded director of photography on The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and The Night of the Hunter (1955), Shock Corridor was shot in two weeks during February 1963 on several barren interior sets for a cost of $222,000.13 Fuller enjoyed complete production control, as well as final cut. Shock Corridor features some of the most extreme characters and situations in all of Fuller’s work. His interest in the clash of opposing elements reaches its apotheosis in this film, as the narrative contrasts real identities with assumed identities, sanity with insanity, and restraint with hysteria. The setting of the film and the nature of Johnny’s interviews provide Fuller with a broad platform to address America’s failings, and his impulse to provoke rather than to be tasteful leads to an abundance of truly alarming sequences. The sensationalism of Shock Corridor thus lies not just in its exposé of contemporary social ills and near-parodic depiction of mental illness, but also in its ability to elicit visceral responses from the viewer, to literally produce shocking sensations through the presentation of narrative and stylistic conflict.

Shock Corridor opens with a portentous quote from Euripides: “Whom God wishes to destroy he first makes mad.” Assisted by Swanee (William Zuckert), his editor, and Dr. Fong (Philip Ahn), a psychiatrist, reporter Johnny (Peter Breck) “trains” to appear mentally ill, but encounters resistance from his girlfriend, Cathy (Constance Towers). After Johnny withdraws his love, Cathy relents and appears before the police, claiming to be Johnny’s sister and the victim of his sexual advances. Johnny succeeds in being committed, bunks with an overweight, gum-smacking opera fanatic, Pagliacci (Larry Tucker), and falls prey to a group of crazed nymphomaniacs. His goal is to interview the three patients who witnessed the murder of Sloan during their brief moments of lucidity: Stuart (James Best), a Korean War veteran who hides behind the identity of a Confederate general to block his guilt over siding with the North Korean Communists; Trent (Hari Rhodes), an African-American who crumbled under the stress of integrating a university and now adopts the identity of a KKK member; and Boden (Gene Evans), a nuclear scientist who regressed to childhood rather than accept responsibility for his deadly creations. While Johnny collects information, he dodges a food fight, a race riot, and Cathy’s growing concerns. The plot gradually suggests the erasure of the division between Johnny’s actual sanity and pretend insanity until his faked symptoms are his real problems and his experience of mental illness matches that of the men he interrogates. After undergoing electroshock therapy, Johnny discovers the name of the killer. He then loses his memory and eventually his mind, freeing the name of the killer—an attendant named Wilkes—whom Johnny subsequently attacks. An epilogue reveals that Johnny regained sanity long enough to write his article, but is now back in the institution. “What a tragedy,” his doctor says. “An insane mute will win the Pulitzer Prize.”

Fuller draws heavily from conventions found in detective stories and social problem pictures in Shock Corridor, but these elements are merely window dressing. The murder mystery appears to be the means to achieve Johnny’s ultimate goal—the Pulitzer Prize—and its overarching structure provides the skeleton of the plot. Yet Johnny’s Clue-like search for who killed Sloan in the kitchen with the butcher knife is actually the film’s MacGuffin. The bulk of the narrative concerns itself not with uncovering a murderer, but with revealing the thin line between sanity and insanity, between what is real and what is imagined. Likewise, the trappings of the psychiatric exposé primarily function as springboards for sensationalism, as generic motivation for antic, extreme behavior, unpredictable action, and gross tastelessness. Setting his story in a “loony bin” freed Fuller to cut loose from logic, causality, and coherence. And cut loose he did. The narrative of Shock Corridor is fraught with implausibility and excessive emotion to an even greater degree than is usual for a Fuller picture, producing a viewing experience that ranges from laughter to disbelief to horror.

Fuller’s goal in Shock Corridor was to use the psychiatric setting to immerse the viewer in a world of conflict and contradiction where opposing forces consistently collide—often within the same person. The ambiguity surrounding role-playing and the difference between sanity and insanity are reflected in the narrative and visual construction of the film. While many of Fuller’s narratives contrast scenes with differing tones, Shock Corridor incorporates opposing elements within individual scenes and characters to blur distinctions, heighten conflict, and throw the viewer off guard. This strategy is first illustrated in the scene following the opening credits, in which Dr. Fong interrogates Johnny. Johnny appears to have sexual feelings for his sister, but when he expresses too much knowledge of fetishism, Dr. Fong cuts him off and throws open the curtains. The viewer is surprised to discover that Johnny is a reporter training to seem like a sex offender, while Dr. Fong is merely his tutor. The status of the relationship between Johnny’s role-play and his core identity supplies the underlying tension of the film, as he must appear unbalanced enough to be believable and trustworthy in the hospital, but must think clearly enough to find the witnesses, ask the right questions, and learn the identity of the killer. Johnny’s obsession with winning the Pulitzer Prize prompts him to remain in the hospital, even as he suffers headaches and hallucinations; yet remaining in the hospital only exposes him to further mental and emotional pressure and the threat of insanity. Johnny’s paradoxical dilemma is mirrored by Cathy’s inner conflict: “I want you, Johnny, but you, you want the Pulitzer Prize.” Like Johnny, Cathy is also a strangely “split” character. A proper, well-dressed woman who references Shakespeare, Dickens, Twain, and Freud (though on wildly inappropriate occasions), Cathy strips for a living, a job whose risks Johnny equates with his role-play: “Those hookers didn’t knock down your guard and the lunatics won’t damage mine!” As part of Johnny’s investigation, Cathy, too, must take on a role, as Johnny’s sister rather than his sweetheart. While the distinction between the two states remains troublingly clear to Cathy, Johnny’s eventual confusion over her identity provides yet another indication of his slide toward madness.

Fuller employs a number of different stylistic techniques to cue viewers to Johnny’s inner thoughts and feelings, thereby allowing us to both objectively recognize and subjectively share his mental decline. Johnny’s voice-over provides background information on the people he encounters, his “plan,” and his experiences. The first time they appear on screen, characters are subject to a brief voice-over biography, complete with hobbies (“Witness number one: Stuart. Farm boy from the Bible Belt.”). As Johnny deceives the doctors and other patients, the voice-over alerts the viewer to the real motives behind his actions and what steps he will take next (“The next question’s got to be about fetishism, according to Dr. Fong’s script.”). When Johnny begins to fall apart, the voice-over also registers his confusion and frustration with what is happening to him (“I’ve got to get my voice back! Don’t panic!”). The voice-over thus acts as narrational shorthand, simultaneously providing exposition and access to Johnny’s conscious thoughts, enabling us to distinguish between when Johnny is pretending to be insane and when he actually is.

Johnny’s superimposed dreams of Cathy early in his hospital stay similarly function to illustrate the divide between his consciousness and unconscious. A Tinker Bell–sized Cathy in strip gear is superimposed on close-up shots of Johnny fidgeting in his sleep. Eerie music provides an aural cue that Johnny is dreaming. The diminutive Cathy tickles Johnny with her boa, speaks in a sexy voice, and taunts him with threats of infidelity: “I don’t like being alone, Johnny, but you made me be alone, Johnny. I have the right to find another Johnny.” These images of Cathy exist in striking contrast to the “real” Cathy in the rest of the film, alerting us to their existence as Johnny’s unconscious fears. Tinker Bell Cathy moves in a different manner, speaks with a different voice, and expresses different concerns than the practical, worried, but supportive real-world Cathy. Johnny talks back to her in his sleep, further revealing his desires: “I miss you, Cathy. My yen for you goes up and down like a fever chart.” Voice-overs and dream sequences are not subtle devices—they explicitly tell the viewer what characters know and how they feel—and Fuller employs them here (as well as his florid dialogue) in a highly suggestive fashion, drawing us in to the already feverish mindset of Johnny.

The dueling roles played by both Johnny and Cathy mirror the divided minds of the psychiatric patients, and Fuller taps this inner conflict to create tension and release repressed emotion. One of the characteristics of the patients is how quickly and easily they shift between restraint and hysteria, sanity and insanity. Johnny adopts this trait as a sign of his own assumed illness when he initially explodes in Dr. Menkin’s office in an effort to be committed. During Johnny’s first meal at the hospital, this behavior is also demonstrated by his fellow patients when a food fight erupts over a disagreement about medication. As no consistent factor sparks these outbursts, they initially take the viewer by surprise; their unexpected appearance in the middle of a scene leaves the viewer in suspense, warily looking for what will set off the next eruption. Dance class, a hallway, a door—inside any space lurks the potential for unleashed emotions and violence. The effect is quite like that produced by the narrative structure of The Steel Helmet: viewers feel that danger may be around any corner, and like the child slowly cranking the jack-in-the-box, anxiously await the next time they’ll get thwacked.

Johnny’s accidental entry into the nymphomaniac ward is a prime example of how Fuller orchestrates the build-up and explosion of emotion for maximum visceral effect. Recalling Johnny’s nightmares of Cathy looking elsewhere for love in his absence, the sequence violently illustrates the effect of thwarted desire, drawing the viewer in as witness and participant. As the segment opens, Johnny’s voice-over of discovery (“Nymphos!”), the extreme close-up of his hand struggling to turn the locked doorknob, and point-of-view editing patterns all highlight his entrapment, binding the viewer to Johnny’s growing fear. Once it becomes clear that Johnny cannot make it out of the room, the formal construction of the scene alters to emphasize the hunger and hysteria of the women’s attack. A high-angle long shot depicts the women encircling Johnny and suddenly throwing him to the floor; the camera cranes down to watch as the women hunch over him like a pack of lions feeding on a baby deer, their heads bobbing to get another bite out of him. The angles, camera movement, and compositions formally position Johnny as a helpless victim and the viewer as one of the manic women. The frenzied emotion expressed in the attackers’ physical actions is intensified by what is going on around them: One woman slowly circles the group singing “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean,” while another scribbles furiously on the wall, chanting “I like coffee, I like tea,” as Johnny begins to cry out in pain. The attack startlingly reduces the confident, smart reporter to quivering sexual bait. By constructing the scene to first visually align us with Johnny and then insert us within the hysterical violence, Fuller encourages us to respond to both the victim’s fear and the attacker’s exhilaration. The thrill of the sequence is decidedly unnerving, leaving the viewer, like Johnny, a bit agog. “Where did that come from?” we wonder.

Fuller provides us with additional clues regarding the experience of mental illness during sequences in which individual patients slip into and out of psychotic episodes. Frequently, subjective sound signals a patient’s initial psychic break, as with the opera music that accompanies Pagliacci’s pantomime of murder, the bugle horns and distorted strings that cue Stuart to dance a frenzied “Dixie,” or the voices inside Bodon’s head. This strategy suggests for the viewer what it is like to be insane—to be unable to distinguish between fantasy and reality—by subjectively presenting the patients’ conflation of what is real and what is imagined. Conversely, a novel narrative and stylistic pattern involving subjective visions punctuates the arrival of clear thought for Stuart, Trent, and Johnny (after he has forgotten the name of the killer). As each character talks, a hallucination sparks his memories and prompts him to recall the past. The visions of Stuart, Trent, and Johnny are marked by a change in film stock, as the movie’s 35mm black-and-white switches to color, 16mm and 35mm unsqueezed anamorphic images of Tokyo, a South American aboriginal tribe, and a waterfall, respectively. The sudden appearance of the subjective images dramatically changes the look of the film, and along with the musical score draws attention to the characters’ resulting moments of lucidity. Here again Fuller exploits the clash of dueling forces—sanity and insanity, reality and fantasy, sound and image—to startle viewers and shake us into an awareness of the patients’ subjective experiences.

Fuller caps the dissolution of the line between Johnny’s real sanity and fake psychosis with two explosive sequences stylistically designed to literally assault the viewer’s senses. First, Johnny’s shock treatment functions as a visual and aural summary of the emotional traumas wrecked by his institutionalization, a barrage of his intermingled fears (insanity) and desires (Cathy). In a silent medium-close-up, Johnny is strapped down on a table with a rag in his mouth and electrodes on his head. When the switch is pulled, he heaves violently. Dialogue and images from previous scenes, including Cathy stripping, Stuart violently dancing to “Dixie,” the nymphos, and the race riot instigated by Trent are superimposed on top of him. The cutting rate of the superimpositions increases rapidly, emphasized by the sound of Johnny screaming above a descending piano scale. Dialogue, image, and score unite in a fevered crescendo that overwhelms the viewer with an excess of stimuli and produces a buildup and release of tension akin to that experienced by Johnny. Both in its cataloguing of traumas and in its visceral effect, the shock treatment presages Johnny’s final hallucination and his complete submersion in insanity.

Johnny’s mental tipping point is the most outrageously “weird” sequence of Fuller’s directorial career, a self-conscious expression of Johnny’s inner torment that astounds, confounds, and exhausts the viewer. The sequence begins with a close-up of Johnny, head in hands, wracking his brain in voice-over to remember the name of the killer. A sound of thunder rumbles, and Johnny looks up. He sticks his hand out; a drop of rain hits his palm, accompanied by a “plink” sound effect. “Did you feel that? It’s beginning to rain,” he tells Pagliacci. Here Fuller stylistically conflates the real and imagined worlds of Johnny. It literally seems to be raining inside, yet logic tells us that it does not rain indoors, and therefore that Johnny must be imagining the rain. Johnny looks down the corridor to his left, prompting the camera to slowly pan left. The camera follows Johnny’s shadow, thrown long and dark across the wall. The hard, low-key side light creates “two” of Johnny, visually illustrating the split in his psyche between light and dark, sanity and insanity. The pan comes to rest on a long shot of the corridor filled with patients. This wide-angle shot, which began on Johnny (objective) and was prompted by his look, now appears to be what he is looking at, i.e., his optical point of view (subjective). The sound of thunder and music continues on the soundtrack, increasing the tension and confusion. The sound track offers the viewer access to what Johnny is thinking, but the visual track confirms that what Johnny thinks is false. The sequence thus mixes objective and subjective stylistic cues rather than clearly delineating a switch to Johnny’s subjectivity. Following another thunderclap, the swelling score accompanies a second cut in to Johnny looking at his hand. The music, as well a shot that repeats the earlier pan but reveals the corridor to be empty, complete the transition into Johnny’s subjectivity. The exact repetition of the pan visually contrasts the real and the imagined: in reality, patients line the corridor, but in Johnny’s mind, he is alone. This sudden change confirms for the viewer that both sound and image are no longer in the realm of reality.

In order to achieve maximum impact, Fuller saves the most formally extreme illustration of hysteria for the moment in which Johnny fully breaches the divide and crosses into insanity. With the transition from objectivity to Johnny’s subjectivity complete, the rest of the sequence abandons any pretense toward maintaining a unified presentation of time, space, and action. The camera reverses its pan down the corridor and moves to the right, across Johnny’s shadow; just as his face enters frame right, the scene cuts to a series of disorienting shots united by fast, disjunctive editing, and accompanied by a crescendo of music, sound effects, and general screeching. Johnny has gone over the edge, and the viewer is subjectively swept along for the ride. Spatial and temporal continuity are no longer maintained: the close-up of Johnny looking left is followed by a long shot of the corridor, flooded with rain, and a drenched Johnny writhing at the far end; the edit suggests that Johnny is looking at himself further down the corridor. This shot is followed by a discontinuous high angle of Johnny sitting on the bench (where we first found him), barely wet. A long shot of Johnny in the corridor, pounding on doors in the rain, cuts to an extreme low angle of his jaw and screeching mouth, protruding from the top of the frame. The highly unusual angle of this shot presents an unnatural view of Johnny, shocking and disorienting the viewer. The effect is multiplied when the shot is used at the end of the sequence, with frame direction reversed. Sound effects of thunder and lightening heighten the subjectivity, while an optical lightening strike cues a series of low-angle color shots of overflowing waterfalls. As with the hallucination sequences of Stuart and Trent, the color shots express what Johnny is seeing; a parallel is created between the visions (and therefore the insanity) of Stuart, Trent, and Johnny. Yet Johnny’s hallucination is even more complex than the others, as it removes all objective mediating devices and completely plunges the viewer into Johnny’s subjectivity. The conflation of objectivity and subjectivity, as well as the use of disjunctive editing, unnatural camera angles, and different film stocks fly in the face of classical rules concerning continuity and clarity, thereby providing the utmost shock to the viewer’s system. When the sequence is complete, the viewer is as drained as Johnny.

Rather than resolving the conflict in a false fashion—as in Forty Guns—or destroying the protagonist—as in The Steel Helmet—the narrative of Shock Corridor accomplishes both: following Johnny’s revelation of the killer to Dr. Cristo, exposition reveals Johnny is released, writes his story, wins his Pulitzer, and embraces his girlfriend—all offscreen—while onscreen he immediately ends up a catatonic mute. This resolution, coupled with the Euripides quote that opens and closes the film, provides Shock Corridor with the appearance of a morality play. The didactic interludes that function as the three witnesses’ backstories also appear to bolster some critics’ contentions that the film posits America as insane. Each of the three witnesses to Sloan’s murder contains in his personal story an indictment of a contemporary American attitude: Stuart suggests Americans are sitting ducks for Communist propaganda if they are not taught to take pride in their country’s history, Trent is a disturbing embodiment of the evils of racism, and Boden warns against Cold War paranoia and nuclear aggression. As with the more didactic passages of Run of the Arrow and China Gate, the personal confessions of the three witnesses feature minimal stylization. The characters are photographed alone in the frame in tight shots, focusing the viewer’s attention on their faces and words. In his moment of lucidity, each man offers a progressive parable, an irrational lesson à la Fuller. The film’s form suggests that widespread social problems—ignorance of history, prejudice, and paranoia—are what made these men insane.

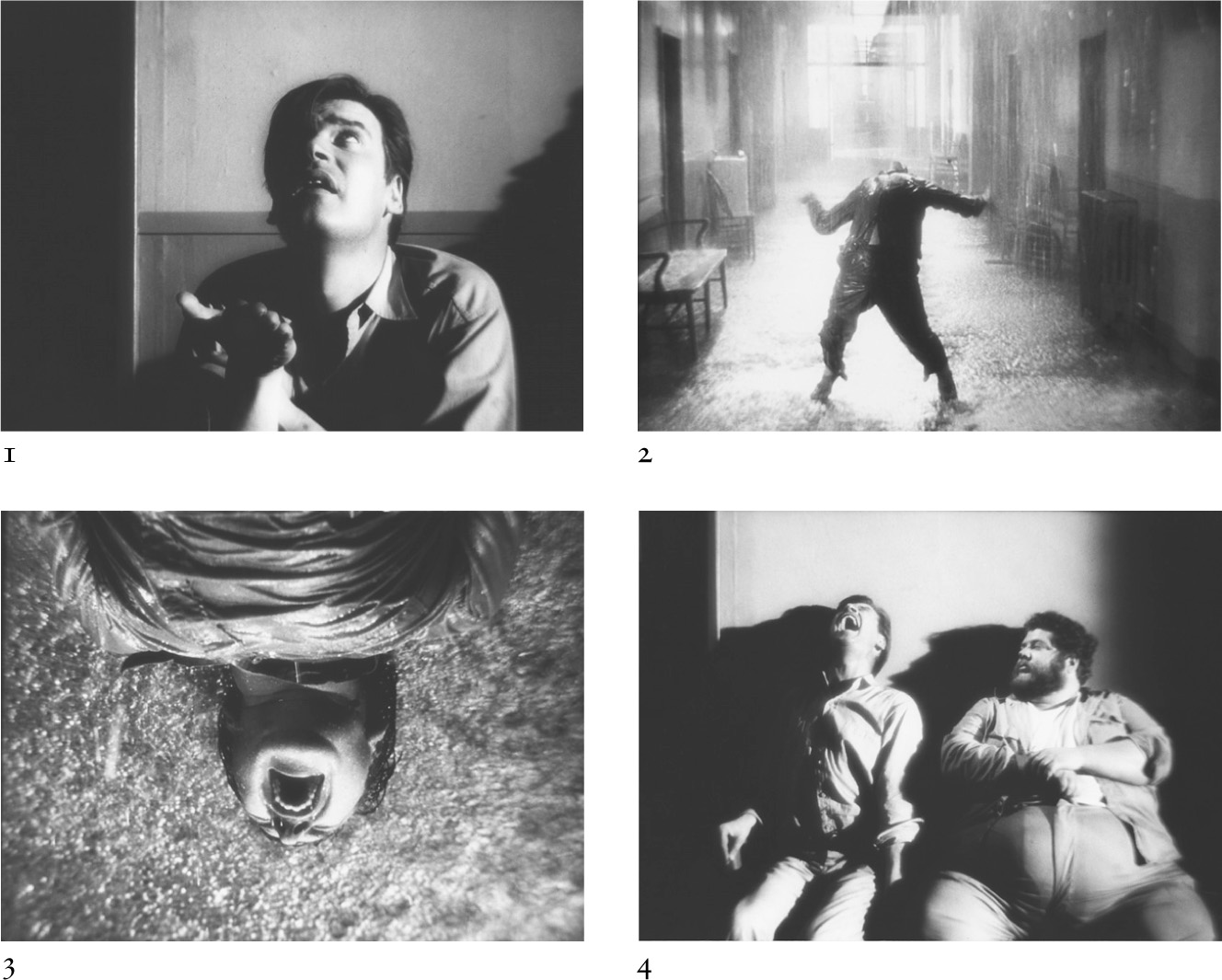

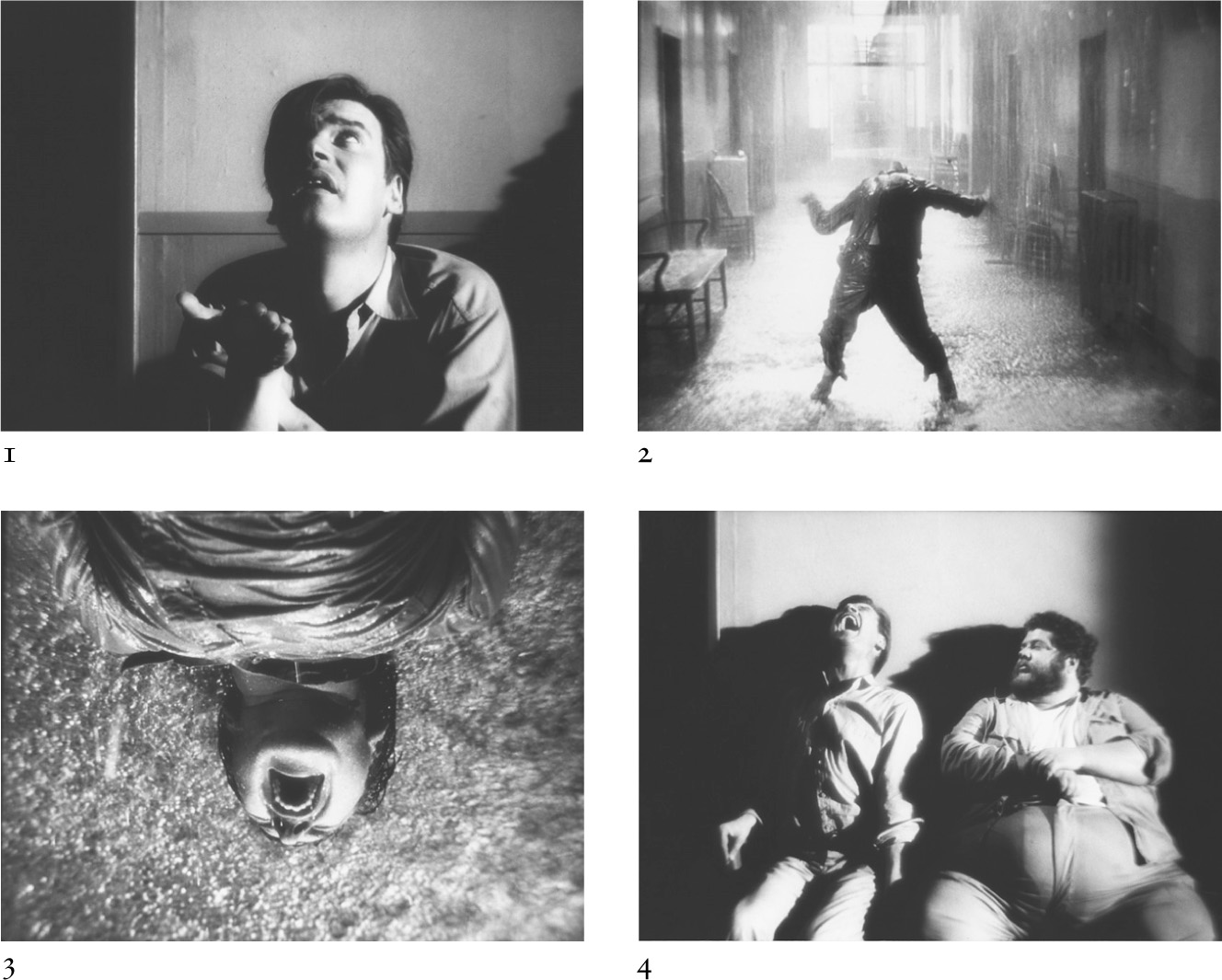

Frame enlargements from Johnny Barrett’s (Peter Breck’s) “weird” mental breakdown in Shock Corridor. Fuller fragments the presentation of space and time from shot to shot floods the hallway with rain to subjectively depict Johnny’s descent into madness.

The characterization of Trent and the presentation of the race riot are perhaps the most jaw-dropping examples of how Fuller presents the viewer of Shock Corridor with a diseased America in a melodramatic manner designed to provoke. The viewer first glimpses Trent walking down the hallway after he lowers a sign he is carrying that reads: “Integration and Democracy Don’t Mix, Go Home Nigger.” The moment is startlingly contradictory on multiple levels. Rhetorically, the sign opposes two ideas, integration and democracy, that are in fact closely aligned, as both are associated with the equal treatment of individuals. The illogical opposition reveals the absurdity of the sentiment, and provokes the viewer to recognize just how undemocratic segregation is. When Trent lowers the sign to reveal that he is African-American, an additional shock is produced, as the person he is telling to go home is himself. Much more so than the schizophrenic identities of Stuart (Confederate general) and Boden (six-year-old child), Trent’s assumed role as a white Klan leader has a powerfully discordant effect. The color of his skin clearly identifies him not only as the opposite of whom he thinks he is, but also as the victim of the very same rabid sentiments he spews.

As the ugliness continues, Trent attempts to attack another black patient, discusses with Johnny the founding of the KKK, and delivers a hate-filled speech about returning America to Americans. On the narrative level, the episodes function both to provide necessary exposition about Trent’s character and as a tool to bring him and Johnny together in solitary confinement so Johnny can witness Trent’s moment of lucidity. At the same time, their timely invocation of civil rights strife, Trent’s role as the riot’s ringleader, and their formal construction all contribute to the sequences’ inflammatory effect. Both rhetorically and physically, the scenes reference the domestic battles that made daily headlines in early-1960s America: lunchroom sit-ins, the integration of schools, the resurgence of the KKK, the strong-arm tactics of the White Citizens’ Council, attacks on Freedom Riders, and lynchings. With the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, that killed four African-American girls occurring just days after the release of Shock Corridor in 1963, the cries of “black bombs for black foreigners” and “America for Americans” reverberating through Trent’s speech gain an alarming authenticity. That the man delivering the sermon and leading the riot is black increases the unsettling effect of the scene just as it highlights the absurdity of the racist rhetoric. During Trent’s speech, increasingly rapid editing, graphic conflict between shots, and extreme changes in shot scale punctuate the gospel of hate, visually and sonically expressing the growing wave of hysteria that is finally broken by Trent’s exhortation, “Let’s get that black boy before he marries my daughter!” that sets off the full scale riot.

A mockup of a lobby card for Shock Corridor illustrates how advertising positioned it as adult exploitation, emphasizing the film’s revelatory nature and its presentation of sex, violence, and controversial material. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theatre Research

Fuller’s creation of such a loud, confident, proud racist was exceedingly bold, and his decision to make the character African-American simply flew in the face of propriety. In 1963, at the height of tension over civil rights, the representation of racist characters in motion pictures was still very circumspect so as not to offend white moviegoers, particularly in the South. Creating an African-American character who hates blacks is something that just was not done—which is precisely why the idea was so perversely appealing for Fuller. Many of Fuller’s films illustrate a willingness—if not an eagerness—to ignore polite conventions of good taste in order to shock the viewer. Of these instances, the character of Trent is perhaps the most disturbing. Trent is a slap in the face—a series of slaps, a barrage—designed to rouse the viewer into an awareness of the hypocrisy of racism. Yet within the context of the murder mystery, Cathy’s stripping, the nymphomaniacs, Stuart’s manic “Dixie” dance, and the assorted chases and fistfights, the viewer understands Trent and the race riot not as a mere polemic, but as an extreme provocation, an attempt to really gut punch the audience. Fuller wants to wake up viewers to truth, but he does this by appealing to us physically and emotionally through conflict and contradiction rather than through reasoned discourse. He still wants to entertain.

With strong exploitation value, major promotion, and organized first-run distribution, Shock Corridor appeared to have more going for it than many of the low-budget films Fuller released through Globe. As the film lacked stars and sported minimal production values, its primary selling point was its sensational material, highlighted in a national promotional campaign that featured publicity in major newspapers and gossip columns as well as print, radio, and television ads emphasizing the sex, violence, and “adults only” content.14 Shock Corridor premiered first-run in September 1963 in New York to “okay” box office at the Palace and the Trans Lux art cinema; the following week the film also bowed in Chicago at the Roosevelt, a theater that catered to fans of action, where returns were “hot.”15 Opening wider in its third week, the film headlined or played at the top of a double bill in medium to small houses and drive-ins in four major cities, ranking seventh in weekly grosses. Shock Corridor garnered widely varying reviews, with some praise in the trades and frequent condemnation in the general press, typified by Film Quarterly’s description of it as “one of the most preposterous and tasteless films of all time.”16 Trade predictions concerning the film’s potential earnings were similarly split; Boxoffice considered it a “strong boxoffice entry” while Variety found the story “so grotesque, so grueling, so shallow and so shoddily sensationalistic that [Fuller’s] message is devastated…. [I]t is difficult to see where [it] can have any really appreciable boxoffice impact.”17 Variety’s prediction largely played out, as exhibitors reported consistently below-average takes during the majority of Shock Corridor’s subsequent first-run dates. Despite Shock Corridor’s top play dates and intensive exploitation campaign, it only returned $128,000 to Allied Artists from the box-office gross, or a little above half of its production costs.18 The film’s extreme didacticism and often crass presentation of mental illness clearly were not well received when it was distributed as the headlining feature in downtown theaters. Although the film would enjoy an extended release in France and eventual cult status in the United States, in 1963 there was little room in the domestic market for such an oddity.

Fuller’s second film for Fromkess-Firks, The Naked Kiss, is also a picture that proves the adage, “One person’s trash is another person’s treasure.” While at the time of its release the guardians of good taste at Cosmopolitan declared it the worst film of the year, many Fuller fans name it as one of his greatest achievements. As was true of Verboten!, The Naked Kiss had few pretensions to even programmer status. Produced for less than $200,000, it was distributed by Allied Artists as a solid B picture. The Naked Kiss reteamed Fuller with cinematographer Stanley Cortez, editor Jerome Thoms, and actress Constance Towers, but still provided him with little in the way of stars, budget, or production value; instead, Fuller amped up the sex and sensationalism. A woman’s picture made for the adult exploitation market, the film concerns a reformed prostitute who falls in love with the leading citizen in a small town, only to discover he is a pedophile. The contrast between truth and appearance, reality and dreams is again a major theme, revealed through visual weirdness and the viewer’s increasing subjective alignment with the protagonist.

The Naked Kiss traces the rise, fall, and eventual redemption of Kelly (Constance Towers), a call girl with a knack for helping children. We first see Kelly angrily beating a man before we know anything about her. The plot then takes her to Grantville, where she arrives fronting as a saleswoman for Angel Foam Champagne and adroitly picks up a police officer named Griff (Anthony Eisley). After she shares her wares with him, Griff tells her Grantville is clean—and subsequently sends her to be a “bon-bon” in a brothel over the river. Rather than take his recommendation, Kelly decides to stay in Grantville and change her life. Tough-talking yet warm-hearted, fiercely independent yet desiring marriage and children, Kelly embodies the contradictory impulses of so many of Fuller’s female characters. She rooms with the town spinster, Miss Josephine (Betty Bronson), and becomes a nurse at an orthopedic hospital for disabled children. Griff, however, questions her motivations, but she insists on her sincerity. Kelly is invited to a party at the house of Grant (Michael Dante), the town’s wealthy benefactor and Griff’s best friend, and makes a visible impression. During a later visit, Grant and Kelly listen to “Moonlight Sonata” and discuss Goethe and Byron; he shows her home movies from Venice and says if she pretends hard enough, she’ll hear the voice of a gondolier. She does, imagining herself in Venice with Grant, and the two kiss. Though the kiss initially repulses her, she brushes away her doubts and returns his affections. Grant and Kelly eventually plan to marry, and when Griff threatens to reveal her past, she tells him Grant already knows. Despite her sordid history, Kelly appears to have found bliss. Then, arriving at Grant’s house one day with her wedding dress, Kelly discovers him molesting a young girl. Grant tells Kelly they are perfect for each other because “We’re both abnormal,” and she promptly whacks him over the head with the phone. Grant’s death turns Griff against Kelly, who is jailed for murder and abandoned by her friends. No one believes Kelly’s discovery about Grant, though it confirms what she first suspected when they initially kissed. Finally Kelly remembers the identity of the child she saw Grant molest, and the attitude of the whole town changes, turning Kelly into a hero. But she has had enough of “polite society.” Through with Grantville, Kelly heads for the next bus out of town.

In this tale of small-town, middle-class hypocrisy, Fuller continues to explore themes of deception and the contradictory nature of truth, carefully manipulating the range and depth of narration to shape the viewer’s perception of Kelly. Fuller introduces the “things are not what they seem” motif right upfront, beginning, as usual, by throwing us for a loop. The Naked Kiss opens with an unstable medium close-up of Kelly’s angry face, her arm moving forward with a purse as if to assault the camera (and the viewer). The second shot, also hand-held and approximating Kelly’s optical point of view, is a medium close-up of a man reeling backward from the blow. A frenzied jazz score accompanies the attack. Whoa! Arriving in the middle of a fight between two unknown people photographed in shaky and violent shots takes the viewer by surprise, focusing attention on the visceral nature of the attack rather than on the reasons behind it. The juxtaposition of action and reaction shots emphasizes graphic conflict and movement from shot to shot, while the score punctuates the explosive nature of the blows. The scene continues, alternating the two medium close-up action-reaction shots and intercutting an occasional low-angle long shot as the two struggle and stumble past a wall of women’s photos. Kelly’s wig comes off; the beautiful blonde is bald! The man finally falls down, and in a medium close-up high angle Kelly squirts him with seltzer and says, “I’m not rolling you, you wretch, I’m only taking what’s coming to me.” Cutting back to the establishing shot, she then counts out $75, kicks him, and goes to put on her wig.

Even more so than the kendo battle in The Crimson Kimono, the visual style of the first scene in The Naked Kiss encourages a visceral response to an ambiguous event. By beginning mid-fight, denying an establishing shot or explanatory dialogue, alternating frontal point-of-view shots, and using a seemingly hand-held camera and a loud, expressive score, the narration overtly undermines any expectation the viewer may have of a conventional, clear introduction to the film’s characters and situations. Instead, the viewer is visually and aurally assaulted, left with an impression of the physical sensation of the event rather than an understanding of the story. As after the wordless opening sequence of Pickup on South Street, the viewer is left to wonder, “What just happened here?” Additionally, as the narration highlights those features of Kelly most likely to elicit shock and disgust, it initially suppresses the potential for a sympathetic emotional response to her character. The cinematography and music accentuate the kinetic force of Kelly’s blows, and the sudden loss of her wig marks her as somewhat of a freak. We are left with a first impression of Kelly as strong, furious, crazed, and rather scary, and we are curious to learn her identity and motivation.

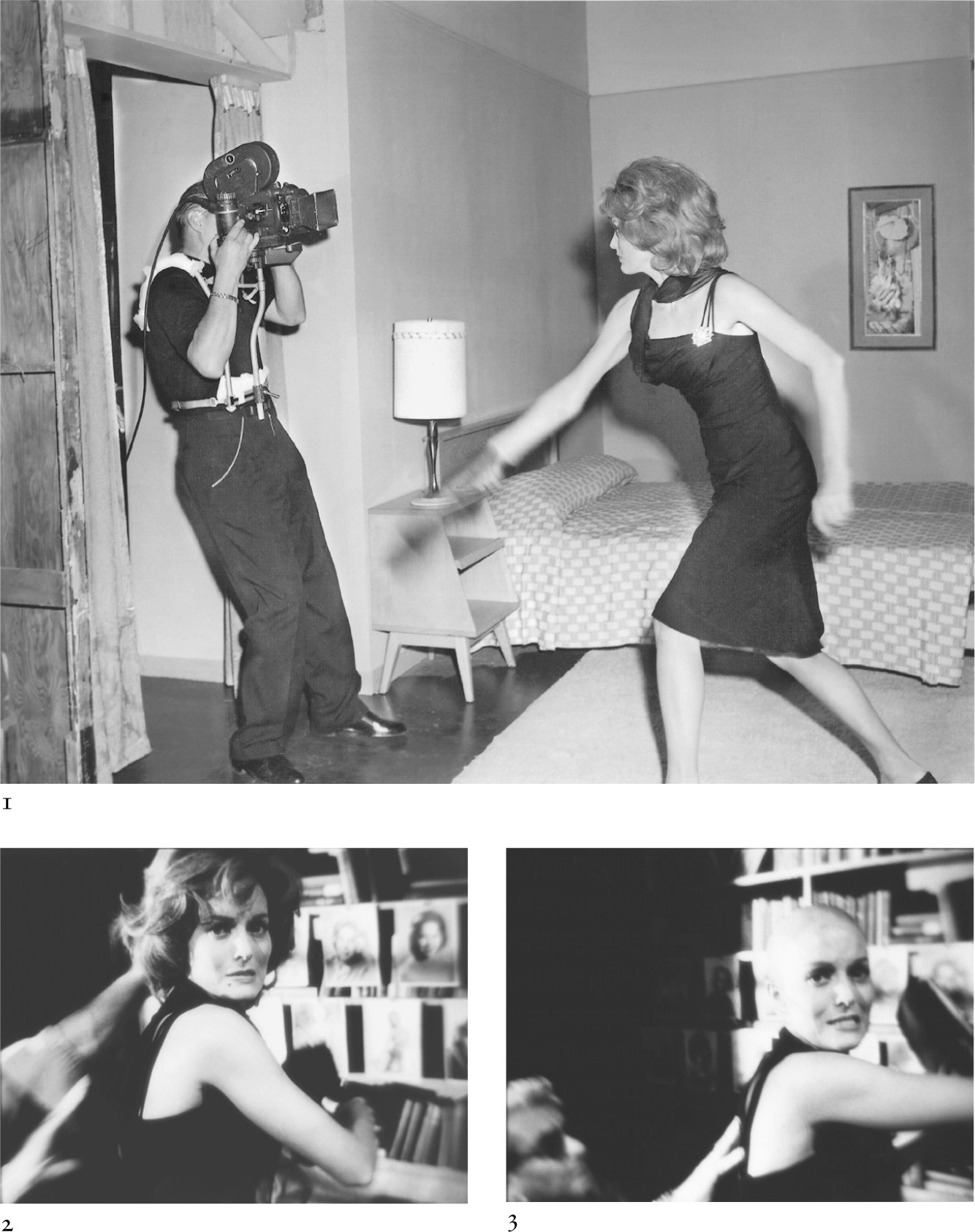

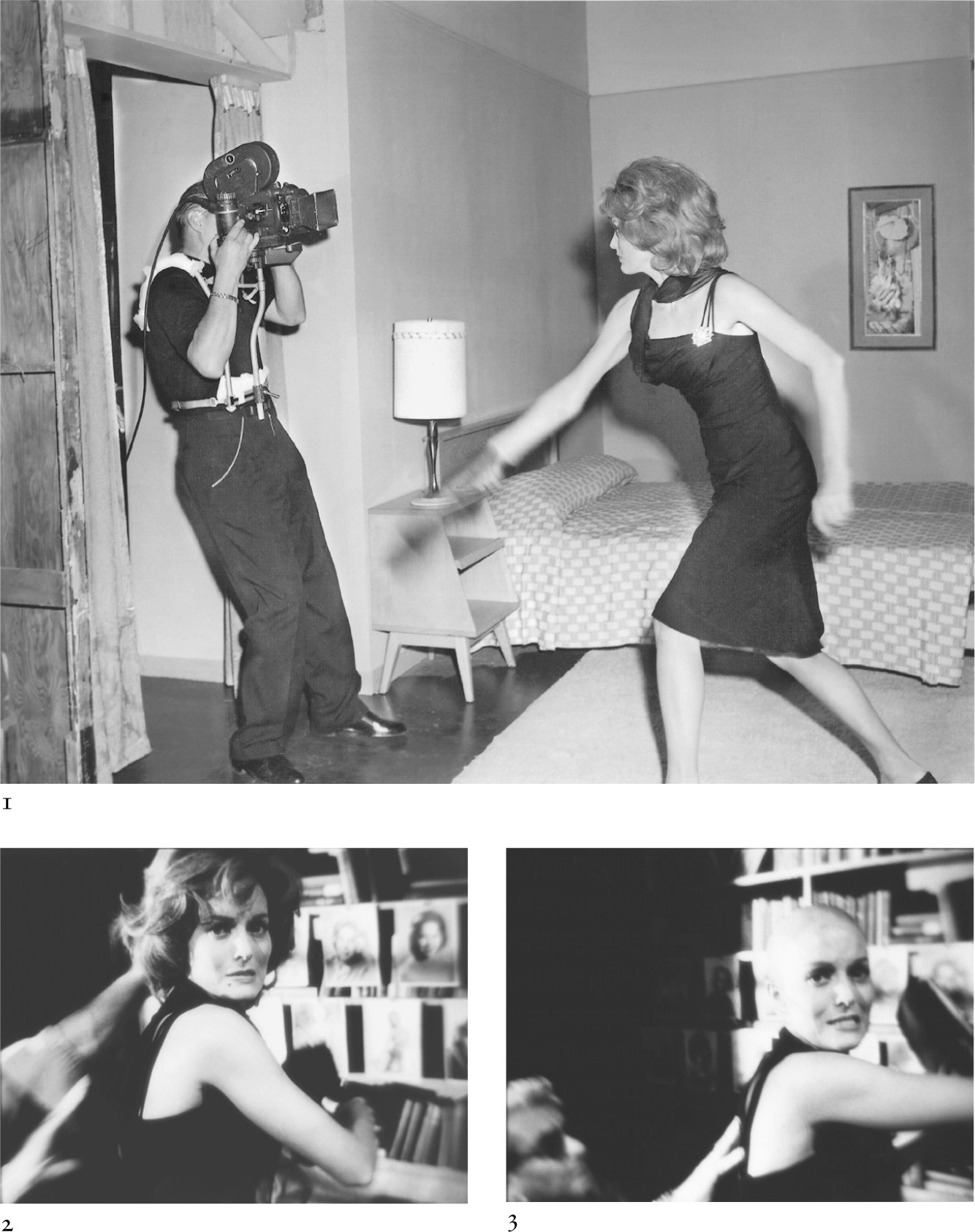

A production still from The Naked Kiss (1) illustrates how the camera operator recorded the kinetic, handheld shots at the beginning of the film. Actress Constance Towers (Kelly) lunges at the camera, while the frame enlargements below (2, 3) reveal Samuel Fuller reaching up to pull off her wig. Fuller moves so quickly his image is captured in only a handful of frames, making his presence invisible to the average viewer and preserving the shocking illusion that the wig merely falls off Towers’s head.

Top image courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

When Kelly arrives in Grantville, Fuller slowly provides information to fill in the gaps, increasing our access to her subjectivity and presenting her as a woman with a dream. At first, the motivations for Kelly’s decision to settle in Grantville and work at the orthopedic hospital are unclear, and given the impact of the opening scene, viewers may suspect, like Griff, that Kelly is a con artist fronting as a “good woman.” Limited access to her subjectivity increases the ambiguity, as little insight into her thoughts and feelings is provided other than what she says and does. Even use of Kelly’s optical point of view is rare. The exceptions to this pattern are telling, however, as they involve interactions concerning children, marriage, and Kelly’s attempt to alter her life: Kelly feeding a bottle to a baby on the street, Miss Josephine’s story of her doomed engagement to the dead Charlie, a disabled child looking to Kelly for approval after walking, and most dramatically, Kelly stating her desire to change and asking Griff to help her. Once we see Kelly working at the hospital, the range and depth of narration dramatically increases, helping the viewer to fill in narrative gaps and clarify Kelly’s traits and desires.

Two parallel dream sequences are key to this process. In the first, Kelly sits with her young patients in the hospital ward and tells them a story about a white swan that pretends hard and is turned into a boy. “And an old man told me if I pretend hard enough, I can play games with the little boy.” The shot then cuts to a subjective vision of Kelly and the kids running and playing in the park. (One child shouts, “I have legs! I have legs!” Again, whoa, but in a weird way.) Within the vision, not only do the children show no signs of physical disability, but Kelly is dressed as a mother, not as a nurse. The framing story of the swan’s wish and the content of the vision suggest that it illustrates Kelly’s dream—for the kids to be healthy and for her to be a mother. Following Kelly’s dramatic declaration to Griff of her desire to leave her life as a prostitute behind and the previous clues regarding her attraction to marriage and motherhood, viewers now suspect that her actions are genuine, and largely disregard initial negative impressions of her.

Several scenes later, a parallel dream sequence takes place with Grant and Kelly, and while only slightly less saccharine than the first, it is substantially more weird. The “Moonlight Sonata” sequence utilizes continuity editing techniques and classical scene construction to unify disparate times and spaces, joining footage from unalike sources into a seamless whole and “normalizing” an explicitly artificial visual presentation. The scene is divided into four segments, each increasing in subjectivity until the kiss in the final segment forces Kelly to question what is a dream and what is real. In the first segment, Grant and Kelly sit on his sofa and pretentiously discuss Venice and Lord Byron, while “Moonlight Sonata” plays on a tape recorder in the background. The segment consists of a frontal shot of them both and two medium-close-up shots of each alone; it establishes the space, cuts into a shot–reverse shot sequence, and reestablishes the space according to classical conventions. Nothing provides an inkling of the weirdness to come—like Kelly, we think everything is normal.

The second segment begins when Grant offers to take Kelly to the place of her dreams—Venice. Much as in the shots preceding Johnny’s breakdown in Shock Corridor, subjective sound effects transition the scene from an objective to a subjective visual presentation. A shot of a flickering film projector is followed by Fuller’s home-movie footage of Venice taken from inside a gondola going down a river. The sound of the flickering projector replaces the “Moonlight Sonata” music and signals a shift toward increasing illusion. The segment continues, cutting between footage of Venice and medium shots of Kelly and Grant on the sofa, with Grant offering a running commentary of the footage. Although no shot actually depicts both the couple and the projected image, their eyelines and commentary lead the viewer to infer that the Venice footage is their optical point of view—i.e., what they are watching on the screen. After a return to a medium shot, Grant asks Kelly if she hears the gondolier singing. A man singing Italian opera rises on the soundtrack, the first indication of the subsequent blending of real and fantasy worlds. A cut to the reverse angle tracks slowly toward Grant as he suggests that if Kelly pretends hard enough, she can hear the gondolier’s voice. The camera then tracks in from the shot of Grant and Kelly together to isolate her in the frame. Kelly tilts her head, looks offscreen, and smiles dreamily. The music and camera movement cue the introduction of a subjective sequence, and as Kelly closes her eyes, the segment cuts to a graphic match of Kelly smiling with her eyes closed, lying on several pillows and listening to the singing. The musical overlap, direct cut, and graphic match elide the spatial discontinuity of the two shots. Set up by the point-of-view editing patterns and the music, the cut seamlessly transforms Kelly from a woman watching a gondola on a movie screen to a woman in a gondola—the gondola of her dreams. Fuller uses the tools of cinema to transform Kelly’s reality into an illusion.

The third segment depicts Kelly’s subjective vision of love with Grant, and its distance from anything resembling reality begs the viewer to question the truth behind the dream. The sequence uses continuity editing techniques to combine the home-movie footage taken from the Venetian gondola with shots of a gondola in which Kelly and Grant lie, surrounded by pillows, in front of a gondolier on a darkened stage, as if the two sets of shots occupy the same time and space. As the stage gondolier begins to plant his pole, the segment cuts to home-movie footage depicting an actual gondolier continuing the same action; as Kelly opens her eyes on stage in a high-angle shot, the segment cuts back to a home-movie low-angle point-of-view shot of a bridge, as if the bridge is Kelly’s optical perspective. Fuller intercuts the two types of footage to suggest that the shots of Venice are now Kelly’s literal point of view—i.e., she is now in a gondola in Venice. Kelly’s gondola, however, is strikingly artificial—it sits immobile, surrounded by darkness, its gondolier seen only from the waist down dipping his pole into thin air. Even the falling leaves look fake. While the continuity editing suggests an integration of the real and imagined Venice, the mise-en-scene self-consciously announces a discrepancy, highlighting the incoherence of the space presented onscreen. The pattern of alternation between the two types of footage continues, and with each return to the shot of Kelly and Grant in the stage gondola, the camera cranes in further, until the couple is actually kissing. Graphic matches, eyeline matches, point-of-view editing patterns, cutting on action, and alternation—all techniques of continuity editing—used in this segment to create the illusion of continuous space and time from shots that clearly are not part of the film’s fictional world. The narrative emphasis on “pretending,” the reflexive foregrounding of the flickering movie projector, and the use of home-movie and theatrically staged footage all work redundantly to suggest that Kelly’s ultimate happiness with the man she loves is a dream that is not rooted in any semblance of reality.

The disorientation evoked by the scene comes to an end with a graphic match between Kelly and Grant kissing in the gondola and them kissing on the sofa, returning the narrative once again to the “real” world. The Italian opera has ceased, replaced only by a silence that punctuates a shift in tone and visual presentation. But something is not quite right: the kiss cuts to Kelly’s optical point of view of Grant, her hands around his neck as she pushes him away. Her disgusted rejection visually suggests what is narratively confirmed only in the last act of the film—that Grant is a sexual predator. Grant’s close-up alternates with the reverse of Kelly, returning the narration to a less self-conscious style but continuing to bind the viewer to her point of view. The camera then slowly tracks in to a close-up of Kelly, who pauses, blinks, smiles, and pulls Grant back toward her, seemingly shaking off any doubts about him. Darkness envelops their faces, and the camera pans down their legs and back to the flickering film projector, a reminder of the power of illusion.

In contrast to Kelly’s attack on the (then) unknown man in the first scene, the visual style in these four segments does not aim to jolt the viewer in a visceral fashion; instead, it hews largely to classical conventions, utilizing analytical editing and alternating shots. What makes the scene “weird” is how these conventions are used. Kelly’s subjective desire to visit Venice with Grant motivates a highly self-conscious sequence that calls attention to the ability of continuity editing to suggest a unified space and time when no such unity actually exists. The net effect is to emphasize the discontinuity of the fictional and fantasy worlds and the false construct of Kelly’s dream. The stylistic presentation of this vision stands in sharp contrast to Kelly’s vision of the children running and playing; the earlier dream world is presented as visually akin to the fictional world, with only a change in characters’ appearances and abilities, while Kelly’s dream with Grant stands apart from the rest of the film, stylistically implicated as an illusion. The visual difference suggests a narrative distinction as well: some dreams are worth chasing (motherhood, health), while others are merely a delusion (Venice, romance with Grant).

The narrative subsequently avoids any further hint of Grant’s undesirability, however, and little information is provided to prepare viewers for the revelation of his crime. As a result, viewers share Kelly’s surprise and horror when she discovers the true sickness at the heart of Grantville. As with the opening, the murder of Grant stands out for its startling content and style, but now style visually aligns us with Kelly rather than depicting her as unhinged and frightening. The scene begins with Kelly happily entering Grant’s darkened house and hearing an unsettling song about mommy and a bluebird, aurally recalling an earlier scene in which Kelly sang with the children at the hospital. A medium shot of Kelly in the living room searching for Grant, wedding gown in hand, cuts to an extreme close-up of her face looking front, at first smiling, then slowly turning to stone. As she glances down and to the right, there is a cut to her optical point of view: a young girl named Bunny looks up, also in a frontal extreme close-up, her face half-darkened by shadow. A long shot follows Bunny’s feet left across the darkened living room as she skips out the door. As during the death of Gunther in Underworld, U.S.A., the constructive editing forces the viewer to piece together the scene’s overall action and the meaning behind it based on what little information is provided in each shot. Because the narration has suppressed the source of the shadow and the spatial relationship between Kelly and Bunny, the action in the segment is initially unclear. Kelly, in extreme close-up as before, glances from left to center, prompting a cut to an extreme frontal close-up of Grant, looking up to meet her eyes. A shot–reverse shot pattern between Kelly and Grant begins, as the lyrics to the song plead, “Mommy, tell me why there are tears in your eyes.” The organization of the sequence around Kelly’s glances sharply restricts the range of narrative information to what she literally sees. The viewer mentally assembles the visual information through her point of view, suspecting as Kelly does that her fiancé has molested Bunny. The high-contrast lighting, dramatic changes in shot scale, eerie song, and unclear spatial relations all emphasize Kelly’s shock at both her discovery and Grant’s subsequent explanation of his actions. Kelly’s disgust, as well as the unsettling close-up of Bunny and the cultural taboo against child molestation, make us squirm in our seats.

In comparison to the opening scene, the visual presentation of Kelly’s assault on Grant downplays the violence of her actions in only five short shots: Kelly switches the wedding-gown box into her left hand; her right hand picks up the receiver of the phone in close-up; in medium shot, she throws her arm forward; the dress and veil fall in front of the camera low to the ground; and the veil settles over the face of a prone Grant as Kelly kneels to collect the gown at the top of the frame. Fuller provides only enough information to suggest the basic action, as viewers never learn exactly what Grant was doing with Bunny or see the details of his murder. In addition, unlike Kelly’s previous assault scenes or those in most Fuller movies, the attack only includes one blow, and the point of contact is elided. The visual style thus presents Kelly’s action as instinctive rather than highlighting the violence of the strike. Fuller is not trying to provoke thrills here so much as recognition of Kelly’s sadness.

As the scene closes, Fuller’s stylistic choices highlight Kelly’s state of shock and contrast her present situation with the promise of the recent past. The scene intercuts frontal medium shots of Kelly blankly staring ahead and folding her wedding gown with high-angle close-ups of the gown box. Sounds of Grant’s projector overlay the shots of the box, aurally recalling Kelly’s subjective visions of love from the “Moonlight Sonata” scene, now dashed. A series of six very short shots of empty spaces in Grant’s house not directly motivated by the action further punctuate the contrast between Kelly’s dreams and how they turned out. The first two shots in the series depict important motifs in Kelly and Grant’s relationship: the tape recorder and the sculpture of Beethoven’s bust; the next three duplicate the camera positions and framing of previous shots when Kelly and Grant were together; the last mirrors Kelly’s point-of-view shot of Bunny running out the front door. Rather than imparting information in and of themselves, the formal union of these disparate shots brings Grant and Kelly’s relationship full circle, illustrating both what brought them together and what tore them apart. The scene ends with an extreme long shot staged in depth of Kelly sitting with her dress box and Grant dead at her feet. Despite the high level of ambiguity in the scene, Fuller’s use of constructive editing underscores the false nature of Grant’s respectability and the complete destruction of Kelly’s dream. Kelly is now broken and alone, eliciting sympathy for her situation and heightening suspense regarding her final fate.

The narrative and visual style throughout The Naked Kiss manipulate the viewer’s understanding of appearances in order to illustrate most effectively the reversal of the moral hierarchy at the heart of the film. By the end, viewers recognize that the seemingly violent prostitute introduced in the opening was an upstanding individual all along; her personal integrity remains strong, regardless of her social standing, while events unmask other more “respectable” citizens for the hypocrites they are. Fuller carefully parcels out the amount and depth of narrative information in order to shape the viewer’s response, using subjectivity and stylistic weirdness in a fashion as daring as in Shock Corridor. Although both films feature many examples of straightforward classical scene construction like the first “Moonlight Sonata” segment, they also demonstrate a distinct willingness to throw the conventional rulebook out the window in order to engage the viewer emotionally with the film. Based on the opening scene alone, or the restrained hysteria of some of the performances, The Naked Kiss might at first appear raw, unbridled, and even “primitive,” but analysis demonstrates just how calculated and intricate its use of visual style is. Fuller takes us on a carefully crafted journey, encouraging us to look beyond appearances and labels, to sift the difference between what is an illusion and what is real.

As with Shock Corridor, The Naked Kiss’s combination of sex and violence is its primary selling point, but it received neither the promotional backing lavished on the earlier film nor the same pattern of intensive first-run distribution. Instead, the film quietly premiered in April 1964 in Constance Towers’s hometown of Whitefish, Montana, before returning in May to headline in Boston and play on the bottom half of a double bill with Allied’s The Strangler (1964) in Chicago.19 The Naked Kiss continued to trickle around the country for assorted supporting dates, finally opening in New York City in late October below Allied’s James Jones World War II–adaptation, The Thin Red Line (1964). While Variety correctly noted that The Naked Kiss “seemed destined for lowercase market in adult situations,” trade notices were routinely positive, and the New York Times declared that the film had “style to burn,” describing Fuller as “one of the liveliest, most visual-minded and cinematographically knowledgeable filmmakers now working in the low-budget Hollywood grist mill.”20 Despite largely enthusiastic critical response to the film, its scattered distribution in flat-fee situations limited box-office potential; given the low returns on Shock Corridor, The Naked Kiss most likely took in even less.

Fuller Goes to Vietnam: The Rifle

While it is impossible to say whether or not the trend in Fuller’s work toward excessive sensationalism would have continued beyond The Naked Kiss if his projects had been produced, an examination of one unproduced script from the mid-1960s suggests that, if anything, his taste for tastelessness was increasing. The Rifle, a Vietnam War picture, both continues the central conflict explored in The Steel Helmet and takes the didacticism and subjectivity of Shock Corridor to a new extreme. Recycling characters, situations, and plot points from earlier Fuller films, the script also features an array of oppositional elements and a melodramatic narrative structure designed to maximize conflict.21 The title refers to an old M1 rifle that is carried by a young Vietnamese boy in the film’s opening shot. A voice-over intones, “This rifle is dedicated to the living who die, the dead who live, the wounded who weep, and to the insane who fake sanity,” recalling familiar themes and highlighting Fuller’s obsession with contradiction. The overarching story concerns Colonel Zack, a Korean War veteran who has adopted a fourteen-year-old Vietnamese boy he discovered during an ambush. Zack promises the boy, Quan, that he will take him back to the United States when his tour of duty completes in a month, but unbeknownst to Zack, Quan is actually a Vietcong soldier who has been ordered to assassinate an American VIP. At the end of the film, Quan mortally wounds the VIP with the M1 rifle given to him by Zack, who must then pursue Quan as the enemy. This plotline lifts the two protagonists from The Steel Helmet and reconfigures their relationship in a more grim and unsentimental fashion, requiring the grizzled father figure to kill the son who betrayed him. The script exploits the conflict between the two by revealing Quan’s allegiance from the beginning, thereby putting the viewer in suspense as to when Zack will discover Quan’s betrayal.

While The Rifle’s central conflict is quite straightforward, it is surrounded by even more sensationalism than in Shock Corridor. Much of the action takes place during an extended patrol of a cast of characters that tests believability, even for a Fuller picture: Zack and Quan, a sergeant, a short timer, a medic, a wounded man, a black soldier named Griff, a draft card burner, a French reporter, a female doctor, a mute disabled boy named Patches, and a nun carrying a baby! Over the course of the patrol, the script reveals the conscientious objector to be both racist and elitist and suggests he uses his opposition to the war as a cover for his cowardice. Zack calls him “punknik” and tells him, “Your education was paid for by a lot of war casualties over the years …. [Draft] dodges are as old as war … and as phony as your principles.” Clearly Fuller was not targeting the youth market with this one. In typical fashion, however, the opposing side fares little better. The French reporter paints a grim picture of the South Vietnamese officers who are America’s allies, suggesting they are “sick with cowardice” and steal food from their own men, who in turn steal from the peasants. The weirdness that Fuller began exploring in Shock Corridor and The Naked Kiss also reappears in an even more jarring fashion during black-and-white scenes of Ho Chi Minh and Mao Tse-tung arguing over Quan’s soul that are intercut with battle sequences. The disregard for social norms and propriety demonstrated in Shock Corridor is here multiplied exponentially, while subjectivity is used overtly for allegorical purposes. There is nothing subtle about this story.

Although the central conflict in The Rifle between Zack and Quan could easily form a sequel to The Steel Helmet, the surrounding narrative is so excessive and so contradictory that it seems unimaginable that the script could ever be made. Here the sensational realism that complemented genre conventions in The Steel Helmet, exploded in Forty Guns, and shifted more heavily toward sensationalism than realism in Shock Corridor has almost completely lost touch with verisimilitude, clarity, and coherence. Fuller’s hard-hitting form of truthtelling stretches didacticism to an extreme and buries yet another surrogate father-son relationship under the weight of so many contradictory impulses the entire project veers toward camp. The Rifle is 1960s Fuller to the nth degree—provocative, excessive, and oblivious to the demands of the market.

The Naked Kiss marked an end to the primary phase of Samuel Fuller’s work as a film director. By the completion of the film’s run, Allied Artists executives reported that the company was seeking producers and creative talent who could supply “all or most of their own financing,” with Allied acting only as distributor.22 For the next two years the company remained mired in debt and unable to finance production or even provide advances to self-financing producers. The Fromkess-Firks deal was thus never completed, and Fuller lost another potential source of money for his films. With no profits to show for his last two releases, he had virtually no chance to form agreements with other distributors. In 1965, Fuller was invited to Paris to write and direct a modern adaptation of Aristophanes’s Lysistrata, but financing fell through. After returning to Los Angeles, Fuller directed five episodes of the television western Iron Horse, two of which he also wrote. It would be fifteen years before his next Hollywood film played in theaters. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Fuller’s films rarely found an audience either as programmers or as low-budget exploitation films, as they operated in a market that reduced the former’s chances for box-office success and primarily rewarded the latter only if targeted at youth. While Fuller continued to seek work as a director and remained an incredibly productive screenwriter, the increasing reliance on profits dictated by independent production effectively ended the initial phase of his domestic filmmaking career.