CHAPTER 10

The Drunkard’s Walk

IN 1814, near the height of the great successes of Newtonian physics, Pierre-Simon de Laplace wrote:

If an intelligence, at a given instant, knew all the forces that animate nature and the position of each constituent being; if, moreover, this intelligence were sufficiently great to submit these data to analysis, it could embrace in the same formula the movements of the greatest bodies in the universe and those of the smallest atoms: to this intelligence nothing would be uncertain, and the future, as the past, would be present to its eyes.1

Laplace was expressing a view called determinism: the idea that the state of the world at the present determines precisely the manner in which the future will unfold.

In everyday life, determinism implies a world in which our personal qualities and the properties of any given situation or environment lead directly and unequivocally to precise consequences. That is an orderly world, one in which everything can be foreseen, computed, predicted. But for Laplace’s dream to hold true, several conditions must be met. First, the laws of nature must dictate a definite future, and we must know those laws. Second, we must have access to data that completely describe the system of interest, allowing no unforeseen influences. Finally, we must have sufficient intelligence or computing power to be able to decide what, given the data about the present, the laws say the future will hold. In this book we’ve examined many concepts that aid our understanding of random phenomena. Along the way we’ve gained insight into a variety of specific life situations. Yet there remains the big picture, the question of how much randomness contributes to where we are in life and how well we can predict where we are going.

In the study of human affairs from the late Renaissance to the Victorian era, many scholars shared Laplace’s belief in determinism. They felt as Galton did that our path in life is strictly determined by our personal qualities, or like Quételet they believed that the future of society is predictable. Often they were inspired by the success of Newtonian physics and believed that human behavior could be foretold as reliably as other phenomena in nature. It seemed reasonable to them that the future events of the everyday world should be as rigidly determined by the present state of affairs as are the orbits of the planets.

In the 1960s a meteorologist named Edward Lorenz sought to employ the newest technology of his day—a primitive computer—to carry out Laplace’s program in the limited realm of the weather. That is, if Lorenz supplied his noisy machine with data on the atmospheric conditions of his idealized earth at some given time, it would employ the known laws of meteorology to calculate and print out rows of numbers representing the weather conditions at future times.

One day, Lorenz decided he wanted to extend a particular simulation further into the future. Instead of repeating the entire calculation, he decided to take a shortcut by beginning the calculation midway through. To accomplish that, he employed as initial conditions data printed out in the earlier simulation. He expected the computer to regenerate the remainder of the previous simulation and then carry it further. But instead he noticed something strange: the weather had evolved differently. Rather than duplicating the end of the previous simulation, the new one diverged wildly. He soon recognized why: in the computer’s memory the data were stored to six decimal places, but in the printout they were quoted to only three. As a result, the data he had supplied were a tiny bit off. A number like 0.293416, for example, would have appeared simply as 0.293.

Scientists usually assume that if the initial conditions of a system are altered slightly, the evolution of that system, too, will be altered slightly. After all, the satellites that collect weather data can measure parameters to only two or three decimal places, and so they cannot even track a difference as tiny as that between 0.293416 and 0.293. But Lorenz found that such small differences led to massive changes in the result.2 The phenomenon was dubbed the butterfly effect, based on the implication that atmospheric changes so small they could have been caused by a butterfly flapping its wings can have a large effect on subsequent global weather patterns. That notion might sound absurd—the equivalent of the extra cup of coffee you sip one morning leading to profound changes in your life. But actually that does happen—for instance, if the extra time you spent caused you to cross paths with your future wife at the train station or to miss being hit by a car that sped through a red light. In fact, Lorenz’s story is itself an example of the butterfly effect, for if he hadn’t taken the minor decision to extend his calculation employing the shortcut, he would not have discovered the butterfly effect, a discovery which sparked a whole new field of mathematics. When we look back in detail on the major events of our lives, it is not uncommon to be able to identify such seemingly inconsequential random events that led to big changes.

Determinism in human affairs fails to meet the requirements for predictability alluded to by Laplace for several reasons. First, as far as we know, society is not governed by definite and fundamental laws in the way physics is. Instead, people’s behavior is not only unpredictable, but as Kahneman and Tversky repeatedly showed, also often irrational (in the sense that we act against our best interests). Second, even if we could uncover the laws of human affairs, as Quételet attempted to do, it is impossible to precisely know or control the circumstances of life. That is, like Lorenz, we cannot obtain the precise data necessary for making predictions. And third, human affairs are so complex that it is doubtful we could carry out the necessary calculations even if we understood the laws and possessed the data. As a result, determinism is a poor model for the human experience. Or as the Nobel laureate Max Born wrote, “Chance is a more fundamental conception than causality.”3

In the scientific study of random processes the drunkard’s walk is the archetype. In our lives it also provides an apt model, for like the granules of pollen floating in the Brownian fluid, we’re continually nudged in this direction and then that one by random events. As a result, although statistical regularities can be found in social data, the future of particular individuals is impossible to predict, and for our particular achievements, our jobs, our friends, our finances, we all owe more to chance than many people realize. On the following pages, I shall argue, furthermore, that in all except the simplest real-life endeavors unforeseeable or unpredictable forces cannot be avoided, and moreover those random forces and our reactions to them account for much of what constitutes our particular path in life. I will begin my argument by exploring an apparent contradiction to that idea: if the future is really chaotic and unpredictable, why, after events have occurred, does it often seem as if we should have been able to foresee them?

IN THE FALL OF 1941, a few months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, an agent in Tokyo sent a spy in Honolulu an alarming request.4 The request was intercepted and sent to the Office of Naval Intelligence. It wended its way through the bureaucracy, reaching Washington in decoded and translated form on October 9. The message requested the Japanese agent in Honolulu to divide Pearl Harbor into five areas and to make reports on ships in the harbor with reference to those areas. Of special interest were battleships, destroyers, and aircraft carriers, as well as information regarding the anchoring of more than one ship at a single dock. Some weeks later another curious incident occurred: U.S. monitors lost track of radio communications from all known carriers in the first and second Japanese fleets, losing with it all knowledge of their whereabouts. Then in early December the Combat Intelligence Unit of the Fourteenth Naval District in Hawaii reported that the Japanese had changed their call signs for the second time in a month. Call signs, such as WCBS or KNPR, are designations identifying the source of a radio transmission. In wartime they reveal the identity of a source not only to friend but also to foe, so they are periodically altered. The Japanese had a habit of changing them every six months or more. To change them twice in thirty days was considered a “step in preparing for active operations on a large scale.” The change made identification of the whereabouts of Japanese carriers and submarines in the ensuing days difficult, further confusing the issue of the radio silence.

Two days later messages sent to Japanese diplomatic and consular posts at Hong Kong, Singapore, Batavia, Manila, Washington, and London were intercepted and decoded. They called for the diplomats to destroy most of their codes and ciphers immediately and to burn all other important confidential and secret documents. Around that time the FBI also intercepted a telephone call from a cook at the Japanese consulate in Hawaii to someone in Honolulu reporting in great excitement that the officials there were burning all major documents. The assistant head of the main unit of army intelligence, Lieutenant Colonel George W. Bicknell, brought one of the intercepted messages to his boss as he was preparing to go to dinner with the head of the army’s Hawaiian Department. It was late afternoon on Saturday, December 6, the day before the attack. Bicknell’s higher-up took five minutes to consider the message, then dismissed it and went to eat. With events so foreboding when considered in hindsight, why hadn’t anyone privy to this information seen the attack coming?

In any complex string of events in which each event unfolds with some element of uncertainty, there is a fundamental asymmetry between past and future. This asymmetry has been the subject of scientific study ever since Boltzmann made his statistical analysis of the molecular processes responsible for the properties of fluids (see chapter 8). Imagine, for example, a dye molecule floating in a glass of water. The molecule will, like one of Brown’s granules, follow a drunkard’s walk. But even that aimless movement makes progress in some direction. If you wait three hours, for example, the molecule will typically have traveled about an inch from where it started. Suppose that at some point the molecule moves to a position of significance and so finally attracts our attention. As many did after Pearl Harbor, we might look for the reason why that unexpected event occurred. Now suppose we dig into the molecule’s past. Suppose, in fact, we trace the record of all its collisions. We will indeed discover how first this bump from a water molecule and then that one propelled the dye molecule on its zigzag path from there to here. In hindsight, in other words, we can clearly explain why the past of the dye molecule developed as it did. But the water contains many other water molecules that could have been the ones that interacted with the dye molecule. To predict the dye molecule’s path beforehand would have therefore required us to calculate the paths and mutual interactions of all those potentially important water molecules. That would have involved an almost unimaginable number of mathematical calculations, far greater in scope and difficulty than the list of collisions needed to understand the past. In other words, the movement of the dye molecule was virtually impossible to predict before the fact even though it was relatively easy to understand afterward.

That fundamental asymmetry is why in day-to-day life the past often seems obvious even when we could not have predicted it. It’s why weather forecasters can tell you the reasons why three days ago the cold front moved like this and yesterday the warm front moved like that, causing it to rain on your romantic garden wedding, but the same forecasters are much less successful at knowing how the fronts will behave three days hence and at providing the warning you would have needed to get that big tent ready. Or consider a game of chess. Unlike card games, chess involves no explicit random element. And yet there is uncertainty because neither player knows for sure what his or her opponent will do next. If the players are expert, at most points in the game it may be possible to see a few moves into the future; if you look out any further, the uncertainty will compound, and no one will be able to say with any confidence exactly how the game will turn out. On the other hand, looking back, it is usually easy to say why each player made the moves he or she made. This again is a probabilistic process whose future is difficult to predict but whose past is easy to understand.

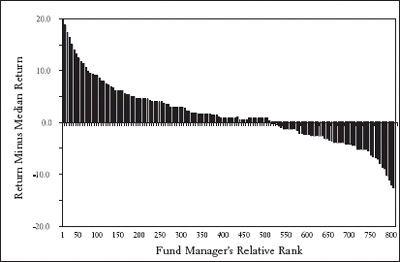

The same thing is true of the stock market. Consider, for instance, the performance of mutual funds. As I mentioned in chapter 9, it is common, when choosing a mutual fund, to look at past performance. Indeed, it is easy to find nice, orderly patterns when looking back. Here, for example, is a graph of the performance of 800 mutual fund managers over the five-year period, 1991–1995.

Performance versus ranking of the top mutual funds in the five-year period 1991–1995.

On the vertical axis are plotted the funds’ gains or losses relative to the average fund of the group. In other words, a return of 0 percent means the fund’s performance was average for this five-year period. On the horizontal axis is plotted the managers’ relative rank, from the number-1 performer to the number-800 performer. To look up the performance of, say, the 100th most successful mutual fund manager in the given five-year period, you find the point on the graph corresponding to the spot labeled 100 on the horizontal axis.

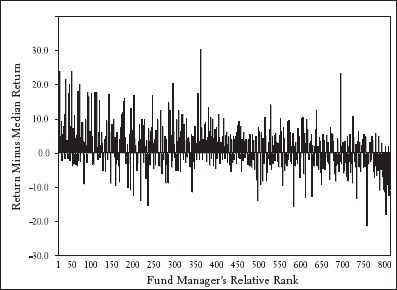

Any analyst, no doubt, could give a number of convincing reasons why the top managers represented here succeeded, why the bottom ones failed, and why the curve should take this shape. And whether or not we take the time to follow such analyses in detail, few are the investors who would choose a fund that has performed 10 percent below average in the past five years over a fund that has done 10 percent better than average. It is easy, looking at the past, to construct such nice graphs and neat explanations, but this logical picture of events is just an illusion of hindsight with little relevance for predicting future events. In the graph on chapter 10, for example, I compare how the same funds, still ranked in order of their performance in the initial five-year period, performed in the next five-year period. In other words, I maintain the ranking based on the period 1991–1995, but display the return the funds achieved in 1996–2000. If the past were a good indication of the future, the funds I considered in the period 1991–1995 would have had more or less the same relative performance in 1996–2000. That is, if the winners (at the left of the graph) continued to do better than the others, and the losers (at the right) worse, this graph should be nearly identical to the last. Instead, as we can see, the order of the past dissolves when extrapolated to the future, and the graph ends up looking like random noise.

People systematically fail to see the role of chance in the success of ventures and in the success of people like the equity-fund manager Bill Miller. And we unreasonably believe that the mistakes of the past must be consequences of ignorance or incompetence and could have been remedied by further study and improved insight. That’s why, for example, in spring 2007, when the stock of Merrill Lynch was trading around $95 a share, its CEO E. Stanley O’Neal could be celebrated as the risk-taking genius responsible, and in the fall of 2007, after the credit market collapsed, derided as the risk-taking cowboy responsible—and promptly fired. We afford automatic respect to superstar business moguls, politicians, and actors and to anyone flying around in a private jet, as if their accomplishments must reflect unique qualities not shared by those forced to eat commercial-airline food. And we place too much confidence in the overly precise predictions of people—political pundits, financial experts, business consultants—who claim a track record demonstrating expertise.

How the top funds in 1991–1995 performed in 1996–2000.

One large publishing company I’m familiar with went to great pains to develop one-year, three-year, and five-year plans for its educational software division. There were high-paid consultants, lengthy marketing meetings, late-night financial-analysis sessions, long offsite afternoon powwows. In the end, hunches were turned into formulas claiming the precision of several decimal places, and wild guesses were codified as likely outcomes. When in the first year certain products didn’t sell as well as expected or others sold better than projected, reasons were found and the appropriate employees blamed or credited as if the initial expectations had been meaningful. The next year saw a series of unforeseen price wars started by two competitors. The year after that the market for educational software collapsed. As the uncertainty compounded, the three-year plan never had a chance to succeed. And the five-year plan, polished and precise as a diamond, was spared any comparison with performance, for by then virtually everyone in the division had moved on to greener pastures.

Historians, whose profession is to study the past, are as wary as scientists of the idea that events unfold in a manner that can be predicted. In fact, in the study of history the illusion of inevitability has such serious consequences that it is one of the few things that both conservative and socialist historians can agree on. The socialist historian Richard Henry Tawney, for example, put it like this: “Historians give an appearance of inevitability…by dragging into prominence the forces which have triumphed and thrusting into the background those which they have swallowed up.”5 And the historian Roberta Wohlstetter, who received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from Ronald Reagan, said it this way: “After the event, of course, a signal is always crystal clear; we can now see what disaster it was signaling…. But before the event it is obscure and pregnant with conflicting meanings.”6

In some sense this idea is encapsulated in the cliché that hindsight is always 20/20, but people often behave as if the adage weren’t true. In government, for example, a should-have-known-it blame game is played after every tragedy. In the case of Pearl Harbor (and the September 11 attacks) the events leading up to the attack, when we look back at them, certainly seem to point in an obvious direction. Yet as with the dye molecule, the weather, or the chess game, if you start well before the fact and trace events forward, the feeling of inevitability quickly dissolves. For one thing, in addition to the intelligence reports I quoted, there was a huge amount of useless intelligence, with each week bringing new reams of sometimes alarming or mysterious messages and transcripts that would later prove misleading or insignificant. And even if we focused on the reports that hindsight tells us were important, before the attack there existed for each of those reports a reasonable alternative explanation that did not point toward a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. For example, the request to divide Pearl Harbor into five areas was similar in style to other requests that had gone to Japanese agents in Panama, Vancouver, San Francisco, and Portland, Oregon. The loss of radio contact was also not unheard of and had in the past often meant simply that the warships were in home waters and communicating via telegraphic landlines. Moreover, even if you believed a broadening of the war was impending, many signs pointed toward an attack elsewhere—in the Philippines, on the Thai peninsula, or on Guam, for example. There were not, to be sure, as many red herrings as water molecules encountered by a molecule of dye, but there were enough to obscure a clear vision of the future.

After Pearl Harbor seven committees of the U.S. Congress delved into the process of discovering why the military had missed all the “signs” of a coming attack. Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall, for one, drew heavy criticism for a May 1941 memo to President Roosevelt in which he wrote that “the Island of Oahu, due to its fortification, its garrison and its physical characteristic, is believed to be the strongest fortress in the world” and reassured the president that, in case of attack, enemy forces would be intercepted “within 200 miles of their objective…by all types of bombardment.” General Marshall was no fool, but neither did he have a crystal ball. The study of randomness tells us that the crystal ball view of events is possible, unfortunately, only after they happen. And so we believe we know why a film did well, a candidate won an election, a storm hit, a stock went down, a soccer team lost, a new product failed, or a disease took a turn for the worse, but such expertise is empty in the sense that it is of little use in predicting when a film will do well, a candidate will win an election, a storm will hit, a stock will go down, a soccer team will lose, a new product will fail, or a disease will take a turn for the worse.

It is easy to concoct stories explaining the past or to become confident about dubious scenarios for the future. That there are traps in such endeavors doesn’t mean we should not undertake them. But we can work to immunize ourselves against our errors of intuition. We can learn to view both explanations and prophecies with skepticism. We can focus on the ability to react to events rather than relying on the ability to predict them, on qualities like flexibility, confidence, courage, and perseverance. And we can place more importance on our direct impressions of people than on their well-trumpeted past accomplishments. In these ways we can resist forming judgments in our automatic deterministic framework.

IN MARCH 1979 another famously unanticipated chain of events occurred, this one at a nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania.7 It resulted in a partial meltdown of the core, in which the nuclear reaction occurs, threatening to release into the environment an alarming dose of radiation. The mishap began when a cup or so of water emerged through a leaky seal from a water filter called a polisher. The leaked water entered a pneumatic system that drives some of the plant’s instruments, tripping two valves. The tripped valves shut down the flow of cold water to the plant’s steam generator—the system responsible for removing the heat generated by the nuclear reaction in the core. An emergency water pump then came on, but a valve in each of its two pipes had been left in a closed position after maintenance two days earlier. The pumps therefore were pumping water uselessly toward a dead end. Moreover, a pressure-relief valve also failed, as did a gauge in the control room that ought to have shown that the valve was not working.

Viewed separately, each of the failures was of a type considered both commonplace and acceptable. Polisher problems were not unusual at the plant, nor were they normally very serious; with hundreds of valves regularly being opened or closed in a nuclear power plant, leaving some valves in the wrong position was not considered rare or alarming; and the pressure-relief valve was known to be somewhat unreliable and had failed at times without major consequences in at least eleven other power plants. Yet strung together, these failures make the plant seem as if it had been run by the Keystone Kops. And so after the incident at Three Mile Island came many investigations and much laying of blame, as well as a very different consequence. That string of events spurred Yale sociologist Charles Perrow to create a new theory of accidents, in which is codified the central argument of this chapter: in complex systems (among which I count our lives) we should expect that minor factors we can usually ignore will by chance sometimes cause major incidents.8

In his theory Perrow recognized that modern systems are made up of thousands of parts, including fallible human decision makers, which interrelate in ways that are, like Laplace’s atoms, impossible to track and anticipate individually. Yet one can bet on the fact that just as atoms executing a drunkard’s walk will eventually get somewhere, so too will accidents eventually occur. Called normal accident theory, Perrow’s doctrine describes how that happens—how accidents can occur without clear causes, without those glaring errors and incompetent villains sought by corporate or government commissions. But although normal accident theory is a theory of why, inevitably, things sometimes go wrong, it could also be flipped around to explain why, inevitably, they sometimes go right. For in a complex undertaking, no matter how many times we fail, if we keep trying, there is often a good chance we will eventually succeed. In fact, economists like W. Brian Arthur argue that a concurrence of minor factors can even lead companies with no particular edge to come to dominate their competitors. “In the real world,” he wrote, “if several similar-sized firms entered a market together, small fortuitous events—unexpected orders, chance meetings with buyers, managerial whims—would help determine which ones received early sales and, over time, which came to dominate. Economic activity is…[determined] by individual transactions that are too small to foresee, and these small ‘random’ events could [ac]cumulate and become magnified by positive feedbacks over time.”9

The same phenomenon has been noticed by researchers in sociology. One group, for example, studied the buying habits of consumers in what sociologists call the cultural industries—books, film, art, music. The conventional marketing wisdom in those fields is that success is achieved by anticipating consumer preference. In this view the most productive way for executives to spend their time is to study what it is about the likes of Stephen King, Madonna, or Bruce Willis that appeals to so many fans. They study the past and, as I’ve just argued, have no trouble extracting reasons for whatever success they are attempting to explain. They then try to replicate it.

That is the deterministic view of the marketplace, a view in which it is mainly the intrinsic qualities of the person or the product that governs success. But there is another way to look at it, a nondeterministic view. In this view there are many high-quality but unknown books, singers, actors, and what makes one or another come to stand out is largely a conspiracy of random and minor factors—that is, luck. In this view the traditional executives are just spinning their wheels.

Thanks to the Internet, this idea has been tested. The researchers who tested it focused on the music market, in which Internet sales are coming to dominate. For their study they recruited 14,341 participants who were asked to listen to, rate, and if they desired, download 48 songs by bands they had not heard of.10 Some of the participants were also allowed to view data on the popularity of each song—that is, on how many fellow participants had downloaded it. These participants were divided into eight separate “worlds” and could see only the data on downloads of people in their own world. All the artists in all the worlds began with zero downloads, after which each world evolved independently. There was also a ninth group of participants, who were not shown any data. The researchers employed the popularity of the songs in this latter group of insulated listeners to define the “intrinsic quality” of each song—that is, its appeal in the absence of external influence.

If the deterministic view of the world were true, the same songs ought to have dominated in each of the eight worlds, and the popularity rankings in those worlds ought to have agreed with the intrinsic quality as determined by the isolated individuals. But the researchers found exactly the opposite: the popularity of individual songs varied widely among the different worlds, and different songs of similar intrinsic quality also varied widely in their popularity. For example, a song called “Lockdown” by a band called 52metro ranked twenty-six out of forty-eight in intrinsic quality but was the number-1 song in one world and the number-40 song in another. In this experiment, as one song or another by chance got an early edge in downloads, its seeming popularity influenced future shoppers. It’s a phenomenon that is well-known in the movie industry: moviegoers will report liking a movie more when they hear beforehand how good it is. In this example, small chance influences created a snowball effect and made a huge difference in the future of the song. Again, it’s the butterfly effect.

In our lives, too, we can see through the microscope of close scrutiny that many major events would have turned out differently were it not for the random confluence of minor factors, people we’ve met by chance, job opportunities that randomly came our way. For example, consider the actor who, for seven years starting in the late 1970s, lived in a fifth-floor walk-up on Forty-ninth Street in Manhattan, struggling to make a name for himself. He worked off-Broadway, sometimes far off, and in television commercials, taking all the steps he could to get noticed, build a career, and earn the money to eat an occasional hanger steak in a restaurant without having to duck out before the check arrived. And like many other wannabes, no matter how hard this aspiring actor worked to get the right parts, make the right career choices, and excel in his trade, his most reliable role remained the one he played in his other career—as a bartender. Then one day in the summer of 1984 he flew to Los Angeles, either to attend the Olympics (if you believe his publicist) or to visit a girlfriend (if you believe The New York Times). Whichever account is accurate, one thing is clear: the decision to visit the West Coast had little to do with acting and much to do with love, or at least the love of sports. Yet it proved to be the best career decision he ever made, most likely the best decision of his life.

The actor’s name is Bruce Willis, and while he was in Los Angeles, an agent suggested he go on a few television auditions.11 One was for a show in its final stages of casting. The producers already had a list of finalists in mind, but in Hollywood nothing is final until the ink on the contract is dry and the litigation has ended. Willis got his audition and landed the role—that of David Addison, the male lead paired with Cybill Shepherd in a new ABC offering called Moonlighting.

It might be tempting to believe that Willis was the obvious choice over Mr. X, the fellow at the top of the list when the newcomer arrived, and that the rest is, as they say, history. Since in hindsight we know that Moonlighting and Willis became huge successes, it is hard to imagine the assemblage of Hollywood decision makers, upon seeing Willis, doing anything but lighting up stogies as they celebrated their brilliant discovery and put to flame their now-outmoded list of finalists. But what really happened at the casting session is more like what you get when you send your kids out for a single gallon of ice cream and two want strawberry while the third demands triple-chocolate-fudge brownie. The network executives fought for Mr. X, their judgment being that Willis did not look like a serious lead. Glenn Caron, Moonlighting’s executive producer, argued for Willis. It is easy, looking back, to dismiss the network executives as ignorant buffoons. In my experience, television producers often do, especially when the executives are out of earshot. But before we make that choice, consider this: television viewers at first agreed with the executives’ mediocre assessment. Moonlighting debuted in March 1985 to low ratings and continued with a mediocre performance through the rest of its first season. Only in the second season did viewers change their minds and the show become a major hit. Willis’s appeal and his success were apparently unforeseeable until, of course, he suddenly became a star. One might at this point chalk up the story to crazy Hollywood, but Willis’s drunkard’s walk to success is not at all unusual. A path punctuated by random impacts and unintended consequences is the path of many successful people, not only in their careers but also in their loves, hobbies, and friendships. In fact, it is more the rule than the exception.

I was watching late-night television recently when another star, though not one from the entertainment world, appeared for an interview. His name is Bill Gates. Though the interviewer is known for his sarcastic approach, toward Gates he seemed unusually deferential. Even the audience seemed to ogle Gates. The reason, of course, is that for thirteen years straight Gates was named the richest man in the world by Forbes magazine. In fact, since founding Microsoft, Gates has earned more than $100 a second. And so when he was asked about his vision for interactive television, everyone waited with great anticipation to hear what he had to say. But his answer was ordinary, no more creative, ingenious, or insightful than anything I’ve heard from a dozen other computer professionals. Which brings us to this question: does Gates earn $100 per second because he is godlike, or is he godlike because he earns $100 per second?

In August 1980, when a group of IBM employees working on a secret project to build a personal computer flew to Seattle to meet with the young computer entrepreneur, Bill Gates was running a small company and IBM needed a program, called an operating system, for its planned “home computer.” Recollections of the ensuing events vary, but the gist goes like this:12 Gates said he couldn’t provide the operating system and referred the IBM people to a famed programmer named Gary Kildall at Digital Research Inc. The talks between IBM and Kildall did not go well. For one thing, when IBM showed up at DRI’s offices, Kildall’s then wife, the company’s business manager, refused to sign IBM’s nondisclosure agreement. The IBM emissaries called again, and that time Kildall did meet with them. No one knows exactly what transpired in that meeting, but if an informal deal was made, it didn’t stick. Around that time one of the IBM employees, Jack Sams, saw Gates again. They both knew of another operating system that was available, a system that was, depending on whom you ask, based on or inspired by Kildall’s. According to Sams, Gates said, “Do you want to get…[that operating system], or do you want me to?” Sams, apparently not appreciating the implications, said, “By all means, you get it.” Gates did, for $50,000 (or, by some accounts, a bit more), made a few changes, and renamed it DOS (disk operating system). IBM, apparently with little faith in the potential of its new idea, licensed DOS from Gates for a low per-copy royalty fee, letting Gates retain the rights. DOS was no better—and many, including most computer professionals, would claim far worse—than, say, Apple’s Macintosh operating system. But the growing base of IBM users encouraged software developers to write for DOS, thereby encouraging prospective users to buy IBM machines, a circumstance that in turn encouraged software developers to write for DOS. In other words, as W. Brian Arthur would say, people bought DOS because people were buying DOS. In the fluid world of computer entrepreneurs, Gates became the molecule that broke from the pack. But had it not been for Kildall’s uncooperativeness, IBM’s lack of vision, or the second encounter between Sams and Gates, despite whatever visionary or business acumen Gates possesses, he might have become just another software entrepreneur rather than the richest man in the world, and that is probably why his vision seems like that of just that—another software entrepreneur.

Our society can be quick to make wealthy people into heroes and poor ones into goats. That’s why the real estate mogul Donald Trump, whose Plaza Hotel went bankrupt and whose casino empire went bankrupt twice (a shareholder who invested $10,000 in his casino company in 1994 would thirteen years later have come away with $636),13 nevertheless dared to star in a wildly successful television program in which he judged the business acumen of aspiring young people.

Obviously it can be a mistake to assign brilliance in proportion to wealth. We cannot see a person’s potential, only his or her results, so we often misjudge people by thinking that the results must reflect the person. The normal accident theory of life shows not that the connection between actions and rewards is random but that random influences are as important as our qualities and actions.

On an emotional level many people resist the idea that random influences are important even if, on an intellectual level, they understand that they are. If people underestimate the role of chance in the careers of moguls, do they also downplay its role in the lives of the least successful? In the 1960s that question inspired the social psychologist Melvin Lerner to look into society’s negative attitudes toward the poor.14 Realizing that “few people would engage in extended activity if they believed that there were a random connection between what they did and the rewards they received,”15 Lerner concluded that “for the sake of their own sanity,” people overestimate the degree to which ability can be inferred from success.16 We are inclined, that is, to see movie stars as more talented than aspiring movie stars and to think that the richest people in the world must also be the smartest.

WE MIGHT NOT THINK we judge people according to their income or outward signs of success, but even when we know for a fact that a person’s salary is completely random, many people cannot avoid making the intuitive judgment that salary is correlated with worth. Melvin Lerner examined that issue by arranging for subjects to sit in a small darkened auditorium facing a one-way mirror.17 From their seats these observers could gaze into a small well-lit room containing a table and two chairs. The observers were led to believe that two workers, Tom and Bill, would soon enter the room and work together for fifteen minutes unscrambling anagrams. The curtains in front of the viewing window were then closed, and Lerner told the observers that he would keep the curtains shut because the experiment would go better if they could hear but not see the workers, so that they would not be influenced by their appearance. He also told them that because his funds were limited, he could pay only one of the workers, who would be chosen at random. As Lerner left the room, an assistant threw a switch that began to play an audiotape. The observers believed they were listening in as Tom and Bill entered the room behind the curtain and began their work. Actually they were listening to a recording of Tom and Bill reading a fixed script, which had been constructed such that, by various objective measures, each of them appeared to be equally adept and successful at his task. Afterward the observers, not knowing this, were asked to rate Tom and Bill on their effort, creativity, and success. When Tom was selected to receive the payment, about 90 percent of the observers rated him as having made the greater contribution. When Bill was selected, about 70 percent of the observers rated him higher. Despite Tom and Bill’s equivalent performance and the observers’ knowledge that the pay was randomly assigned, the observers perceived the worker who got paid as being better than the one who had worked for nothing. Alas, as all of those who dress for success know, we are all too easily fooled by the money someone earns.

A series of related studies investigated the same effect from the point of view of the workers themselves.18 Everyone knows that bosses with the right social and academic credentials and a nice title and salary have at times put a higher value on their own ideas than on those of their underlings. Researchers wondered, will people who earn more money purely by chance behave the same way? Does even unearned “success” instill a feeling of superiority? To find out, pairs of volunteers were asked to cooperate on various pointless tasks. In one task, for instance, a black-and-white image was briefly displayed and the subjects had to decide whether the top or the bottom of the image contained a greater proportion of white. Before each task began, one of the subjects was randomly chosen to receive considerably more pay for participating than the other. When that information was not made available, the subjects cooperated pretty harmoniously. But when they knew how much they each were getting paid, the higher-paid subjects exhibited more resistance to input from their partners than the lower-paid ones. Even random differences in pay lead to the backward inference of differences in skill and hence to the development of unequal influence. It’s an element of personal and office dynamics that cannot be ignored.

But it is the other side of the question that was closer to the original motivation for Lerner’s work. With a colleague, Lerner asked whether people are inclined to feel that those who are not successful or who suffer deserve their fate.19 In that study small groups of female college students gathered in a waiting room. After a few minutes one was selected and led out. That student, whom I will call the victim, was not really a test subject but had been planted in the room by the experimenters. The remaining subjects were told that they would observe the victim working at a learning task and that each time she made an incorrect response, she would receive an electric shock. The experimenter adjusted some knobs said to control the shock levels, and then a video monitor was turned on. The subjects watched as the victim entered an adjoining room, was strapped to a “shock apparatus,” and then attempted to learn pairs of nonsense syllables.

During the task the victim received several apparently painful electric shocks for her incorrect responses. She reacted with exclamations of pain and suffering. In reality the victim was acting, and what played on the monitor was a prerecorded tape. At first, as expected, most of the observers reported being extremely upset by their peer’s unjust suffering. But as the experiment continued, their sympathy for the victim began to erode. Eventually the observers, powerless to help, instead began to denigrate the victim. The more the victim suffered, the lower their opinion of her became. As Lerner had predicted, the observers had a need to understand the situation in terms of cause and effect. To be certain that some other dynamic wasn’t really at work, the experiment was repeated with other groups of subjects, who were told that the victim would be well compensated for her pain. In other words, these subjects believed that the victim was being “fairly” treated but were otherwise exposed to the same scenario. Those observers did not develop a tendency to think poorly of the victim. We unfortunately seem to be unconsciously biased against those in society who come out on the bottom.

We miss the effects of randomness in life because when we assess the world, we tend to see what we expect to see. We in effect define degree of talent by degree of success and then reinforce our feelings of causality by noting the correlation. That’s why although there is sometimes little difference in ability between a wildly successful person and one who is not as successful, there is usually a big difference in how they are viewed. Before Moonlighting, if you were told by the young bartender Bruce Willis that he hoped to become a film star, you would not have thought, gee, I sure am lucky to have this chance to chat one-on-one with a charismatic future celebrity, but rather you would have thought something more along the lines of yeah, well, for now just make sure not to overdo it on the vermouth. The day after the show became a hit, however, everyone suddenly viewed Bruce Willis as a star, a guy who has that something special it takes to capture viewers’ hearts and imagination.

The power of expectations was dramatically illustrated in a bold experiment conducted years ago by the psychologist David L. Rosenhan.20 In that study each of eight “pseudopatients” made an appointment at one of a variety of hospitals and then showed up at the admissions office complaining that they were hearing strange voices. The pseudopatients were a varied group: three psychologists, a psychiatrist, a pediatrician, a student, a painter, and a housewife. Other than alleging that single symptom and reporting false names and vocations, they all described their lives with complete honesty. Confident in the clockwork operation of our mental health system, some of the subjects later reported having feared that their obvious sanity would be immediately sniffed out, causing great embarrassment on their part. They needn’t have worried. All but one were admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The remaining patient was admitted with a diagnosis of manic-depressive psychosis.

Upon admission, they all ceased simulating any symptoms of abnormality and reported that the voices were gone. Then, as previously instructed by Rosenhan, they waited for the staff to notice that they were not, in fact, insane. None of the staff noticed. Instead, the hospital workers interpreted the pseudopatients’ behavior through the lens of insanity. When one patient was observed writing in his diary, it was noted in the nursing record that “patient engages in writing behavior,” identifying the writing as a sign of mental illness. When another patient had an outburst while being mistreated by an attendant, the behavior was also assumed to be part of the patient’s pathology. Even the act of arriving at the cafeteria before it opened for lunch was seen as a symptom of insanity. Other patients, unimpressed by formal medical diagnoses, would regularly challenge the pseudopatients with comments like “You’re not crazy. You’re a journalist…you’re checking up on the hospital.” The pseudopatients’ doctors, however, wrote notes like “This white 39-year-old male…manifests a long history of considerable ambivalence in close relationships, which begins in early childhood. A warm relationship with his mother cools during adolescence. A distant relationship with his father is described as being very intense.”

The good news is that despite their suspicious habits of writing and showing up early for lunch, the pseudopatients were judged not to be a danger to themselves or others and released after an average stay of nineteen days. The hospitals never detected the ruse and, when later informed of what had gone on, denied that such a scenario could be possible.

If it is easy to fall victim to expectations, it is also easy to exploit them. That is why struggling people in Hollywood work hard to look as though they are not struggling, why doctors wear white coats and place all manner of certificates and degrees on their office walls, why used-car salesmen would rather repair blemishes on the outside of a car than sink money into engine work, and why teachers will, on average, give a higher grade to a homework assignment turned in by an “excellent” student than to identical work turned in by a “weak” one.21 Marketers also know this and design ad campaigns to create and then exploit our expectations. One arena in which that was done very effectively is the vodka market. Vodka is a neutral spirit, distilled, according to the U.S. government definition, “as to be without distinctive character, aroma, taste or color.” Most American vodkas originate, therefore, not with passionate, flannel-shirted men like those who create wines, but with corporate giants like the agrochemical supplier Archer Daniels Midland. And the job of the vodka distiller is not to nurture an aging process that imparts finely nuanced flavor but to take the 190-proof industrial swill such suppliers provide, add water, and subtract as much of the taste as possible. Through massive image-building campaigns, however, vodka producers have managed to create very strong expectations of difference. As a result, people believe that this liquor, which by its very definition is without a distinctive character, actually varies greatly from brand to brand. Moreover, they are willing to pay large amounts of money based on those differences. Lest I be dismissed as a tasteless boor, I wish to point out that there is a way to test my ravings. You could line up a series of vodkas and a series of vodka sophisticates and perform a blind tasting. As it happens, The New York Times did just that.22 And without their labels, fancy vodkas like Grey Goose and Ketel One didn’t fare so well. Compared with conventional wisdom, in fact, the results appeared random. Moreover, of the twenty-one vodkas tasted, it was the cheap bar brand, Smirnoff, that came out at the top of the list. Our assessment of the world would be quite different if all our judgments could be insulated from expectation and based only on relevant data.

A FEW YEARS AGO The Sunday Times of London conducted an experiment. Its editors submitted typewritten manuscripts of the opening chapters of two novels that had won the Booker Prize—one of the world’s most prestigious and most influential awards for contemporary fiction—to twenty major publishers and agents.23 One of the novels was In a Free State by V. S. Naipaul, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature; the other was Holiday by Stanley Middleton. One can safely assume that each of the recipients of the manuscripts would have heaped praise on the highly lauded novels had they known what they were reading. But the submissions were made as if they were the work of aspiring authors, and none of the publishers or agents appeared to recognize them. How did the highly successful works fare? All but one of the replies were rejections. The exception was an expression of interest in Middleton’s novel by a London literary agent. The same agent wrote of Naipaul’s book, “We…thought it was quite original. In the end though I’m afraid we just weren’t quite enthusiastic enough to be able to offer to take things further.”

The author Stephen King unwittingly conducted a similar experiment when, worried that the public would not accept his books as quickly as he could churn them out, he wrote a series of novels under the pseudonym Richard Bachman. Sales figures indicated that even Stephen King, without the name, is no Stephen King. (Sales picked up considerably after word of the author’s true identity finally got out.) Sadly, one experiment King did not perform was the opposite: to swathe wonderful unpublished manuscripts by struggling writers in covers naming him as the author. But if even Stephen King, without the name, is no Stephen King, then the rest of us, when our creative work receives a less-than-Kingly reception, might take comfort in knowing that the differences in quality might not be as great as some people would have us believe.

Years ago at Caltech, I had an office around the corner from the office of a physicist named John Schwarz. He was getting little recognition and had suffered a decade of ridicule as he almost single-handedly kept alive a discredited theory, called string theory, which predicted that space has many more dimensions than the three we observe. Then one day he and a co-worker made a technical breakthrough, and for reasons that need not concern us here, suddenly the extra dimensions sounded more acceptable. String theory has been the hottest thing in physics ever since. Today John is considered one of the brilliant elder statesmen of physics, yet had he let the years of obscurity get to him, he would have been a testament to Thomas Edison’s observation that “many of life’s failures are people who did not realize how close they were to success when they gave up.”24

Another physicist I knew had a story that was strikingly similar to John’s. He was, coincidentally, John’s PhD adviser at the University of California, Berkeley. Considered one of the most brilliant scientists of his generation, this physicist was a leader in an area of research called S-matrix theory. Like John, he was stubbornly persistent and continued to work on his theory for years after others had given up. But unlike John, he did not succeed. And because of his lack of success he ended his career with many people thinking him a crackpot. But in my opinion both he and John were brilliant physicists with the courage to work—with no promise of an imminent breakthrough—on a theory that had gone out of style. And just as authors should be judged by their writing and not their books’ sales, so physicists—and all who strive to achieve—should be judged more by their abilities than by their success.

The cord that tethers ability to success is both loose and elastic. It is easy to see fine qualities in successful books or to see unpublished manuscripts, inexpensive vodkas, or people struggling in any field as somehow lacking. It is easy to believe that ideas that worked were good ideas, that plans that succeeded were well designed, and that ideas and plans that did not were ill conceived. And it is easy to make heroes out of the most successful and to glance with disdain at the least. But ability does not guarantee achievement, nor is achievement proportional to ability. And so it is important to always keep in mind the other term in the equation—the role of chance.

It is no tragedy to think of the most successful people in any field as superheroes. But it is a tragedy when a belief in the judgment of experts or the marketplace rather than a belief in ourselves causes us to give up, as John Kennedy Toole did when he committed suicide after publishers repeatedly rejected his manuscript for the posthumously best-selling Confederacy of Dunces. And so when tempted to judge someone by his or her degree of success, I like to remind myself that were they to start over, Stephen King might be only a Richard Bachman and V. S. Naipaul just another struggling author, and somewhere out there roam the equals of Bill Gates and Bruce Willis and Roger Maris who are not rich and famous, equals on whom Fortune did not bestow the right breakthrough product or TV show or year. What I’ve learned, above all, is to keep marching forward because the best news is that since chance does play a role, one important factor in success is under our control: the number of at bats, the number of chances taken, the number of opportunities seized. For even a coin weighted toward failure will sometimes land on success. Or as the IBM pioneer Thomas Watson said, “If you want to succeed, double your failure rate.”

I have tried in this book to present the basic concepts of randomness, to illustrate how they apply to human affairs, and to present my view that its effects are largely overlooked in our interpretations of events and in our expectations and decisions. It may come as an epiphany merely to recognize the ubiquitous role of random processes in our lives; the true power of the theory of random processes, however, lies in the fact that once we understand the nature of random processes, we can alter the way we perceive the events that happen around us.

The psychologist David Rosenhan wrote that “once a person is abnormal, all of his other behaviors and characteristics are colored by that label.”25 The same applies for stardom, for many other labels of success, and for those of failure. We judge people and initiatives by their results, and we expect events to happen for good, understandable reasons. But our clear visions of inevitability are often only illusions. I wrote this book in the belief that we can reorganize our thinking in the face of uncertainty. We can improve our skill at decision making and tame some of the biases that lead us to make poor judgments and poor choices. We can seek to understand people’s qualities or the qualities of a situation quite apart from the results they attain, and we can learn to judge decisions by the spectrum of potential outcomes they might have produced rather than by the particular result that actually occurred.

My mother always warned me not to think I could predict or control the future. She once related the incident that converted her to that belief. It concerned her sister, Sabina, of whom she still often speaks although it has been over sixty-five years since she last saw her. Sabina was seventeen. My mother, who idolized her as younger siblings sometimes do their older siblings, was fifteen. The Nazis had invaded Poland, and my father, from the poor section of town, had joined the underground and, as I said earlier, eventually ended up in Buchenwald. My mother, who didn’t know him then, came from the wealthy part of town and ended up in a forced-labor camp. There she was given the job of nurse’s aide and took care of patients suffering from typhus. Food was scarce, and random death was always near. To help protect my mother from the ever-present dangers, Sabina agreed to a plan. She had a friend who was a member of the Jewish police, a group, generally despised by the inmates, who carried out the Germans’ commands and helped keep order in the camp. Sabina’s friend had offered to marry her—a marriage in name only—so that Sabina might obtain the protections that his position afforded. Sabina, thinking those protections would extend to my mother, agreed. For a while it worked. Then something happened, and the Nazis soured on the Jewish police. They sent a number of officers to the gas chambers, along with their spouses—including Sabina’s husband and Sabina herself. My mother has lived now for many more years without Sabina than she had lived with her, but Sabina’s death still haunts her. My mother worries that when she is gone, there will no longer be any trace that Sabina ever existed. To her this story shows that it is pointless to make plans. I do not agree. I believe it is important to plan, if we do so with our eyes open. But more important, my mother’s experience has taught me that we ought to identify and appreciate the good luck that we have and recognize the random events that contribute to our success. It has taught me, too, to accept the chance events that may cause us grief. Most of all it has taught me to appreciate the absence of bad luck, the absence of events that might have brought us down, and the absence of the disease, war, famine, and accident that have not—or have not yet—befallen us.