Near the end of the last Ice Age, roughly 10,000 years ago, Joshua Tree was a very different place. During the Ice Age massive glaciers had advanced over much of North America, pushing the Jet Stream south and with it the heavy rains of the Pacific Northwest. California’s deserts were transformed into lush, green environments filled with rivers and lakes, including a river that flowed through Pinto Basin in the southern half of Joshua Tree National Park. During this time creatures such as mammoths, mastodons, and camels wandered the grassy plains. But when global temperatures rose and the glaciers melted, the Jet Stream retreated and the climate of Southern California started to dry out.

As early as 8,000 years ago, primitive humans were living in Pinto Basin. By the time of their arrival, many large Ice Age animals had gone extinct (most likely due to overhunting) and the river that once flowed through Pinto Basin had dried up. Very little is known about the Pinto Culture. The only evidence we have of their existence comes from stone tools and spear points discovered by archaeologists in the 1930s. The abundance of spear points suggests that the Pinto Culture was a mobile population heavily dependant upon large game. Hunters attached stone points to wooden spears, and used spear throwers (atlatls) to hurl their weapons at animals. People of the Pinto Culture may have occupied Pinto Basin for as long as 4,000 years, but ultimately they decided to move on.

Several thousand years later, Serrano and Cahuilla Indians arrived in the park. Both tribes visited Joshua Tree on a seasonal basis, taking advantage of food resources when they were abundant and moving on when food was more plentiful somewhere else. The largest village in the park was located at the Oasis of Mara, and it was occupied by a small band of Serrano Indians. The Serrano spent their winters at the Oasis of Mara and other locations in the northern half of the park. They spent their summers in the cooler pine forests of the San Bernardino Mountains to the west. The Cahuilla Indians, meanwhile, occupied sites in southern parts of the park, which marked one of the northern limit’s of their range. Both tribes belonged to the Uto-Aztecan language family of Indians, and they were often connected through rituals, intermarriage, and trade. But despite their close ties and close proximity, the Serrano and Cahuilla remained two distinct tribes.

There were only so many ways to scrape out a living in the desert, however, and in terms of day-to-day activities the Serrano and Cahuilla were virtually identical. The same was true of most desert tribes in Southern California, where the harsh environment forced them to adapt in remarkably similar ways. The limited resources kept population densities low. Villages generally consisting of 25 to 100 individuals—a stark contrast to Indians living on the coast where natural resources were abundant and village populations sometimes topped 1,000.

Desert Indians were hunters and gatherers, but up to three-quarters of their diet consisted of plants. Acorns, mesquite beans, and pine nuts were their most important sources of food, but they ate over 100 different varieties of plants. Because different plants have different growing seasons, desert Indians were highly mobile, moving from one harvesting site to another throughout the year.

Desert Indians generally avoided hunting large animals like bobcats and bighorn sheep. Instead they focused their energy on smaller animals such as jackrabbits and rodents, which were more plentiful, less dangerous, and much easier to hunt. Their weapons included bows, arrows, and throwing sticks similar to boomerangs that were used to break animals’ legs. Rodents that hid in rock crevices or holes were extracted with long, forked sticks that were twisted into the animal’s fur. But desert Indians were not particularly picky eaters, and their diet also included snakes, lizards, and insect larvae. Crickets were sometimes roasted as a condiment for acorn mush. Despite their appetite for just about anything that moved, they were also known to keep animals such as dogs, birds, and reptiles as pets.

In the winter, desert Indians wore clothing made of animal skins. In the summer they wore few clothes at all. Indian women were highly skilled weavers, and they spent much of their time weaving plant fibers from yuccas and palm trees into hats, sandals, and practical items such as baskets, netting, and rope. A women’s social prestige within the tribe was often based on her weaving ability. Pottery was also common among desert Indians, and earthenware vessels called ollas were used to store water and food.

Serrano and Cahuilla Indians lived in thatched huts made from palm fronds. Each family lived in a circular house with a central fire pit, but most daily routines took place outside. During the day, Indians often sat in the shade of a ramada, a thatched canopy supported by four poles. Villages also had several communal structures such as buildings for storage, a sauna-like sweat house, and a large ceremonial room where the village leader lived.

Although each village had a leader, daily life revolved around the family. Family members depended on one another for survival, and the close bonds they developed lay at the heart of Indian society. The importance of family was reflected in their vocabulary—the Cahuilla had over 60 words to describe relatives and relationships.

Both the Serrano and the Cahuilla split their tribe into two distinct groups called moieties, based on male family lineage. The two moieties—Tukum (“Wildcats”) and Wahilyam (“Coyotes”)—served mostly as marriage guides; a Wildcat could marry a Coyote, but not another Wildcat (and vice versa). These rules ensured a healthy and diverse gene pool. It also forced Indians to seek partners outside of their local village, strengthening overall alliances within the tribe.

Of all the world’s early human cultures, only in North America did complex inland societies evolve in the absence of agriculture. All other complex societies, from the Egyptians to the Aztecs, fueled their development on irrigated crops, which are highly nutritious and capable of mass production. But Indians north of Mexico were not only able to survive without large-scale farming, they advanced to the point of developing complex, multi-tiered societies run by ruling elites and distinguished by ritual specialists and skilled craftsmen. Anthropologists had once assumed that agriculture was essential for such a feat. The Indians of North America proved them wrong.

What made the Indian’s situation different was North America’s staggering abundance of natural resources. Even away from the lush, coastal regions, the continent’s unique topography lent itself to a wilderness flush with wild game and edible plants. Although both were eaten, plants were the most important food source. And from the deserts of California to the forests of New England, the most important plants were oak trees for the acorns they provided.

In other parts of the world, nuts are covered in shells so thick you need a hammer to open them (think macadamias and brazils). But North American varieties are different. Here, nuts like acorns are thin-shelled and easy to open. They are also highly nutritious and can be harvested in huge quantities. At large oak groves, a single adult can collect several tons of acorns over the course of a two-week harvest. Acorns can also be stored for up to a year without spoiling because of the presence of a natural preservative called tannin. Tannin increases the acorn’s shelf-life, but it also makes them bitter and unpalatable (it’s the same chemical used to tan leather). To make the acorns edible, Indians would grind them into an oily meal which was then filtered repeatedly with water to leach out the tannin. The resulting flour was then cooked into a gruel-like soup or tortilla-style flatbread.

The autumn acorn harvest was such an important event to the Indians of Southern California that elaborate rituals and ceremonies developed around it. When the acorns finally ripened in the fall, village leaders would proclaim a three-day festival of feasting, singing and dancing to celebrate the new crop.

By most accounts the Serrano and Cahuilla led happy, comfortable lives. Although natural resources were limited in the desert, the Indians made the most of them, and both tribes generally enjoyed peaceful relations with their neighbors. The combined population of the Serrano and Cahuilla tribes probably never exceeded more than 3,000 individuals, but each tribe contributed to California’s unique native culture.

By the time Columbus set sail there were roughly 100,000 Indians living in California, representing about 60 or so individual tribes. When Spain defeated the Aztecs in Mexico in 1521, all of Mexico fell under its control. Two decades later, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo sailed north from Mexico to explore the coast of California. Although Cabrillo recorded favorable impressions of the land, Spain saw little in the way of economic opportunity. California lay a half world away from European centers of trade, and for the next two centuries California served mostly as a backdrop for smugglers sailing between Mexico and the Orient. But when Russian fur trappers began venturing down the California coast in the mid-1700s, Madrid immediately took notice. To “guard the dominions from all invasion and insult,” Spanish officials ordered the construction of 21 missions along the California coast—a turn of events that would have a profound impact on the Serrano and Cahuilla tribes.

In 1771 Mission San Gabriel Archangel was constructed in present-day Los Angeles. This marked the first European presence anywhere near Serrano and Cahuilla territory, but the two tribes were only indirectly affected. Although Spanish goods sometimes drifted into the desert along Indian trade networks, there was little contact with European settlers. In 1772 Pedro Fages, a Spanish military officer, became the first European to enter the Mojave Desert when he went looking for military deserters. But Fages’ journey was brief and of little consequence.

Four years later, a Franciscan missionary named Francisco Garcés undertook the first meaningful European exploration of California’s deserts—a 2,000-mile trek that lasted 11 months. Garcés “went native,” adopting the clothes and eating habits of the desert tribes and chronicling their behavior in his journal. Among other things, he noted a thriving Indian slave trade carried out by the Mohave Indians, the largest and most powerful tribe he encountered.

For the most part, however, the Spanish avoided the deserts. They were far more focused on their growing problems along the coast. Uprisings among Mission Indians were becoming common. Those Indians who managed to escape the mission often fled to the remote deserts and mountains to the east. While there, they recruited local Indians to perform raids on Mission flocks. To bring these more remote tribes under control, the Spaniards built a second, interior chain of Mission outposts called asistencias that ran parallel to those on the coast.

In 1819 Mission San Gabriel built an asistencia in Redlands, less than 40 miles from present-day Joshua Tree National Park. Serrano and Cahuilla Indians living near Redlands were soon under Spanish control, but more distant villages, such as the Oasis of Mara, were still sheltered by the rugged Little San Bernardino Mountains.

Just two years after the asistencia in Redlands was established, the Mexican Revolution ended Spanish control of California. Within a few years the Mission system dissolved. The Indian transition into Mission life had been a difficult one, but the transition out proved just as taxing. Many former Mission Indians were hired as cheap labor by the powerful Mexican ranchers who now controlled the region. But the ranchers stayed clear of the deserts, allowing the Indians who lived there to carry on their traditional lifestyle.

A few decades later, explorers from the east began arriving in California. Most were destined for the coast, but several passed through Serrano and Cahuilla territory along the way. Fur trapper Jedediah Smith crossed the Mojave Desert north of Joshua Tree in 1826, and Kit Carson followed in his footsteps a few years later. When explorer John Fremont passed through the Mojave in 1844, he noted: “From all that I heard and saw I should say that humanity here appears in its lowest form and in its most elemental state.” He then went on to describe the Joshua Tree as “the most repulsive tree in the vegetable kingdom.”

Fremont’s gruff description was typical of white attitudes towards deserts at the time. In the days before air conditioning and automobiles, deserts were considered deadly, hostile terrain—a stereotype that was well justified. The first Spanish expedition into the desert was only organized after a group of military deserters fled there hoping they wouldn’t be followed, and only a handful of expeditions were organized after that. By the time the United States gained control of California in 1848, its deserts were among the most remote and unexplored regions in the country. But all that was about to change.

On January 24, 1848, nine days before Mexico officially handed California over to the United States, gold was discovered in Northern California. Although both countries were unaware of this fact when the papers were signed, within a few months the biggest gold rush in the history of the world was on. Prior to the discovery of gold, there were only a few thousand white settlers living in California. In 1849 alone, over 80,000 people flooded the state. Ten years later, California’s population was nearing 400,000.

California was booming, but the tidal wave of humanity was concentrated almost entirely in the northern half of the state. In 1860, over a full decade after the Gold Rush kicked off, Los Angeles was still a small cattle ranching town with a little over 2,000 full-time residents. The deserts to the east were even more untouched. In 1853 a scout for the U.S. Railroad Survey wrote of the region surrounding Joshua Tree: “Nothing is known of this country. I have never heard of a white man who had penetrated it.”

Since the arrival of the Spanish, California’s deserts had acted as a kind of natural barrier between the Indians that lived there and the settlers clustered along the coast. During the first decade of the Gold Rush, when Indian populations across much of the state were decimated, tribes living in the remote deserts remained relatively unaffected. But in 1863 this natural barrier was shattered when a smallpox epidemic swept through Los Angeles and headed east. Within a matter of weeks, many Serrano and Cahuilla had fallen ill.

For centuries desert shaman had treated sick Indians by sending them into sweat houses (enclosed shacks heated by a small fire) where sick Indians sweated profusely for hours. This treatment was believed to cleanse the body and promote health. But the results were disastrous when applied to smallpox. Sweating rapidly increased the rate of transmission, and soon the virus had blanketed the desert. Indian populations plummeted, and whole villages were abandoned. Within a matter of months, the social and political structures that had governed desert Indians for centuries started to fall apart.

The Serrano at the Oasis of Mara were among those who abandoned their village. When the survivors returned a few years later, they found a group of Chemeheuvi Indians living among the palms. The Chemeheuvi (sometimes called the Southern Paiute) were the eastern neighbors of the Serrano, but a series of wars with the more powerful Mohave Indians along the Colorado River had driven them west.

Both tribes had fallen on hard times, and they agreed to peacefully share the resources at the oasis. But the Chemeheuvi and Serrano were both facing the end of traditional Indian life. As new settlers continued to arrive in California, Indian populations continued to decline. By the late 1800s over 75 percent of California’s Indians had died due to disease and warfare. A government report issued near the end of the century summed up California’s Indian situation in one tidy sentence: “Never before in history has a people been swept away with such terrible swiftness.”

Smallpox critically weakened the Indians at the Oasis of Mara, but the final blow came from the rapid development of Southern California in the late 1800s. By the 1850s, ranchers from San Bernardino were driving their cattle into the Mojave Desert, and soon they were venturing into the protected valleys and grasslands in the northern half of Joshua Tree National Park.

Ranching in the desert required about 17 acres per adult animal. But ranchers were often on the go, moving seasonally in search of adequate food and water. As one early rancher put it, “In those days, if you were a cowpuncher, you had a pair of chaps, a horse and a pack horse, a bedroll, salt, staples, a six-shooter, and a big chew of tobacco.” The ranchers were the first white men to become familiar with the area, and they built a network of primitive access roads. Many roads were simply improved Indian trails, but their impact on the region was dramatic.

By the mid-1850s the gold fields in Northern California had started to dwindle, and thousands of prospectors fanned out across the state in search of the next big strike. A handful of these prospectors wandered along the roads that led into Joshua Tree, and in 1863 gold was discovered near the Oasis of Mara. Suddenly, the Indians living at the oasis found themselves sharing its resources with a handful of prospectors. At first the prospectors stayed briefly, but in 1879 the region received its first permanent white settler: Bill McHaney. Just 20 years old, McHaney wound up staying in the area until his death nearly 60 years later. Naturally friendly, he got along so well with the Indians that they showed him the locations of nearby trails, water holes, and deposits of gold.

But the region’s defining moment came in 1883, when a prospector named Lew Curtis wandered into the foothills 15 miles east of the Oasis of Mara and discovered deposits so rich that the ground was literally speckled with gold. When the news leaked out, hundreds of prospectors flocked to the area and a boomtown named Dale rose up nearby.

At its rough and tumble peak, Dale was home to over 1,000 citizens—almost one-tenth the size of Los Angeles at the time. Most of Dale’s citizens lived in mobile tent structures that could easily be moved to be closer to new strikes. In its early years, Dale’s location shifted several times. When the town finally settled down, it included a general store, post office, blacksmith, and saloon. A small shack on a hill overlooking Dale constituted the red light district, jokingly referred to as the “Mayor’s Residence.”

Dale’s first residents collected placer gold—small bits of gold eroded from rich veins and scattered along the surface. When the placer gold was gone, the prospectors turned their attention to the lode deposits buried deep in the surrounding hills. But lode mining was extremely expensive, and as this point well-capitalized mining companies arrived in Dale. Before long, many of the town’s citizens were salaried employees.

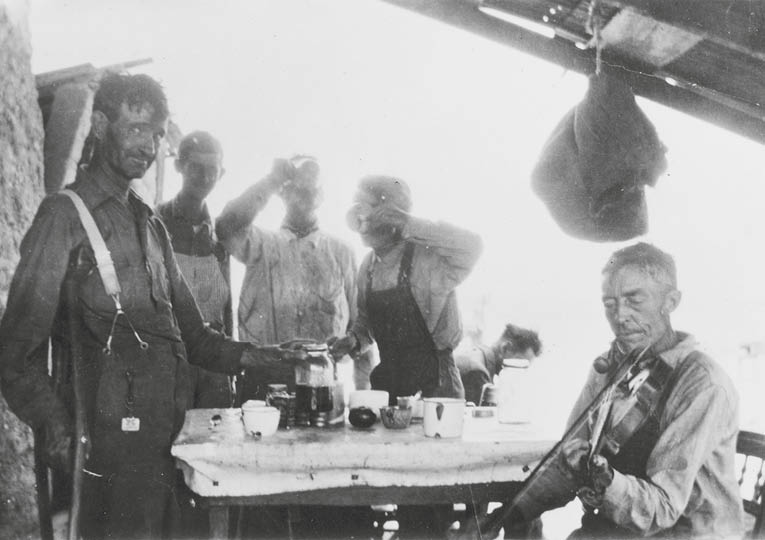

After working all day in the mines, Dale’s residents would descend on the town center in the early evening to gamble and drink into the night. Because there were only a handful of buildings in town, most activities took place outside at tables illuminated by kerosene lanterns. Dale’s saloon was reserved for the town’s most important citizens, a group that included mine owners, engineers, assayers and shift foremen. The saloon boasted a primitive air-conditioning system that consisted of a wall of canvas that was kept constantly wet. As water evaporated off the canvas, the inside of the saloon was cooled.

But creature comforts were few and far between in Dale, especially for the working class. Miners worked long physical hours, often in triple-digit heat, and those prospectors who weren’t employed by the mining companies often came home empty-handed. Water, pumped in from a well north of town, arrived in Dale tinted brown with minerals and salts. Such living conditions were more than most people could bear. After a few years, the town’s population dropped dramatically. Prospectors that did stay continued to scour the region for gold, and occasionally they found it. By the turn of the century, a handful of mines had been discovered within Joshua Tree National Park that rivaled those at Dale, most notably Lost Horse and Desert Queen Mines. For the next several decades, mining operations flourished in Joshua Tree.

Millions of years ago, gold-bearing magma welled up below Joshua Tree and seeped into cracks in the bedrock. After cooling and hardening, the magma formed long quartz veins speckled with gold particles. Over time, erosion exposed the quartz veins, and small grains of “placer” gold spread out across the landscape. (Placer is Spanish for “pleasure”—a reference to the relative ease of gathering this form of gold.) When prospectors first arrived in Joshua Tree in the late 1800s, they collected the small grains of placer gold by dry washing. This involved gathering gold-rich soil in a pan and repeatedly tossing the soil in the air, letting the wind blow away the lighter soil particles and leaving the heavier gold particles behind. Although dry washing was time consuming, it was an easy and inexpensive way to collect gold. Once the placer gold was gone, prospectors turned to the “lode” gold found in the underground quartz veins. They mined massive quantities of quartz ore, which was processed by stamp mills to separate the gold particles from the rest of the rock. Miners were lucky to extract ¼ ounce of gold from one ton of crushed ore.

1. Small Chunks of crushed ore are placed in a mesh chamber.

2. A heavy iron cylinder, the “stamp,” moves up and down, pulverizing the ore into a fine rock powder.

3. The rock powder is flushed out with water, spreading a mushy pulp over the amalgam board.

4. Gold particles chemically cling to mercury on the amalgam board while other particles are washed away. The gold and mercury mixture is then scraped and heated until the mercury vaporizes, leaving gold behind.

In the late 1800s, the dirt roads that led many white settlers into the region around Joshua Tree were also leading many Indians out. Indians at the Oasis of Mara began accepting seasonal employment at nearby ranches, and for a few months families would live at a ranch and collect a steady paycheck. Although Indians were adapting to the modern world, they were also competing directly with poor whites for jobs, and racial tensions flared. Unsolved crimes were often blamed on innocent Indians, and raids sometimes took place in which Indians were brutally hunted down. Towards the end of the century, one government employee concluded that, “Race prejudice is too strong in Southern California to secure a fair administration of justice.”

Discrimination from whites was a fact of life in the region, but Indians were also facing problems from within their own tribes. Poverty, alcoholism, and a new generation of young Indians fascinated by white culture were all taking their toll on traditional Indian life. As tribal elders passed away, there were fewer young Indians left to replace them, and those that could were sometimes reluctant to do so. This inter-generational tension soon came to a breaking point when two young Indians living at the Oasis of Mara fell deeply in love.

In 1909 a 27-year-old Chemeheuvi named Willie Boy became romantically involved with Carlota Boniface, the 16-year-old daughter of one of the leading elders of the Chemeheuvi tribe. When Willie Boy approached Carlota’s father, Old Mike Boniface, for permission to marry, Willie Boy was vehemently denied. Both Willie Boy and Carlota belonged to the same tribal moiety, and traditional Indian culture forbid them from marrying. Old Mike was furious that Willie Boy would even consider the prospect.

Shortly after Old Mike Boniface’s denial, Willie Boy and Carlota ran away into the desert together. Within a few hours, Old Mike tracked down the couple and confronted Willie Boy at gunpoint. The young lovers were brought back to the village and physically separated.

A few months later, Willie Boy shot Old Mike Boniface at point blank range and fled into the desert with Carlota at his side. A white posse from the nearby town of Banning was organized to capture the pair, but by the time they left, the couple had a six-hour head start.

The posse returned to Banning three days later with the body of Carlota Boniface. As a horrified crowd gathered, the men explained that she had been shot by Willie Boy when she slowed his escape. According to the posse, he had left her for dead and continued running on his own.

Carlota’s murder marked a pivotal turning point in the Willie Boy saga. Prior to her death, many whites had brushed off Old Mike’s murder as an Indian dispute that did not concern them. There was even something secretly thrilling about two young Indians running away in the name of love. Carlota’s murder changed all that. Suddenly, Willie Boy was no longer a misguided lover but a cold-blooded killer motivated by raw savagery. For decades white settlers had been fighting to civilize the West. Willie Boy’s actions represented an affront to their accomplishments. On a much darker level, it also confirmed the suspicions of many settlers regarding the “true” nature of Indian behavior.

Within 24 hours of the first posse’s return, reward posters were printed and a second posse was dispatched. As interest in the manhunt grew, local newspapers battled to scoop one another. Their coverage soon degenerated into tabloid fiction playing up popular Western stereotypes. Willie Boy was described as a “red-skinned lady killer” as “fickle as he was gallant in affairs of the heart.” When one of the posse members claimed, with no evidence, that an empty bottle of whiskey had been found in Willie Boy’s bedroom, a paper reported that Willie Boy had consumed, “a suitcase full of whiskey” before shooting Mike Boniface. Before long, a half dozen other gratuitous killings had been added to his record.

For the next several days, Willie Boy used a combination of cunning and speed to elude the posse. He headed east toward Nevada before cutting back to the San Bernardino Mountains, just west of Joshua Tree. As the posse approached the mountains, Willie Boy’s tracks started to include a narrow line in the sand. He was dragging his rifle. They were finally wearing him down.

Willie Boy’s tracks led to Ruby Mountain, located on the western fringe of the San Bernardino Mountains, and as the posse approached the mountain Willie Boy fired at them from above. One man was seriously wounded. The rest fired back and sought cover. Words and shots were exchanged throughout the day, but the wounded man’s serious condition forced the posse to withdraw. Just before the posse left, a final shot echoed from the mountain. No bullet landed anywhere near the men.

Within hours, news of the shootout reached Banning, and newspapers went to press with heavily fictionalized accounts of the event. While Banning newspapers dished out sensationalized Willie Boy gossip, the town of Riverside, located near Banning, was preparing for the arrival of President William Taft, who was in the middle of a cross-country speaking tour. Taft was followed by an entourage of East Coast reporters. When the reporters learned of the manhunt, they jumped on the story. New York editorial pages were soon fretting that Willie Boy represented a credible threat to the President’s life, and newspapers across the country began covering the manhunt.

As outrageous Willie Boy rumors swirled around the nation, a third posse was approaching Ruby Mountain. As they neared the spot where Willie Boy had last been seen, they found his body lying on the ground. It was bloated and sunburned. A rifle lay by his side. At the end of the shootout with the second posse, Willie Boy had removed his shoe, pointed his rifle at his chest, and pulled the trigger with his big toe.

The gruesome discovery of Willie Boy’s body brought the matter to a close. But in the aftermath of the manhunt, most Indians living at the Oasis of Mara decided to leave the village for good. Some believed it was now haunted by evil spirits, but many were simply fed up with the challenge of living there. For decades the Indians at the Oasis of Mara had been involved in a bitter land dispute with Southern Pacific Railroad, and the bad press generated by the Willie Boy incident ultimately tipped the scales in the railroad’s favor. Only two Indians, an elderly couple named Jim and Matilda Pine, refused to leave the village, insisting on spending their final days near the graves of their children. By 1912, however, the Pines were also gone.

Decades after the Willie Boy manhunt ended, some Willie Boy scholars concluded that the posse’s story was a lie. They believed it was a posse member, not Willie Boy, that shot Carlota. According to this theory, when Carlota could no longer keep up with Willie Boy, he tried to hide her and then lead the posse away on his own. When the posse approached Carlota’s hiding spot, they saw a figure moving in the distance and fired. When they drew near, they realized they had shot Carlota. The murder of the 16-year-old girl they were trying to rescue was a disaster. To cover up the situation, the men pinned the murder on Willie Boy. Scholars point out that when Carlota’s body was “discovered,” it was surrounded by most of Willie Boy’s supplies, including a precious canteen of water. Why Willie Boy would abandon his supplies and murder the girl he loved is indeed a mystery.

The departure of the Indians from the Oasis of Mara marked a notable shift in the character of the region. For the next several decades, local culture would be defined entirely by white miners, cattlemen and homesteaders. The most legendary member of this group of hardscrabble settlers was a man named Bill Keys, who arrived in 1910 and spent most of his life within the boundaries of Joshua Tree National Park.

Keys came to Twentynine Palms at the age of 30, having spent much of his youth wandering the Southwest. He became superintendent of the once profitable Desert Queen Mine, but shortly after his arrival the mining company he worked for went bankrupt. As compensation for back wages, Keys was offered the deed to the mine, which he gladly accepted. Before long, he had homesteaded 160 acres and built himself a nearby ranch.

Several years later, on a rare trip to Los Angeles, Keys wandered into a department store and met a young saleswoman named Frances May Lawton. In 1918 the two were married. Frances moved in with Bill at his remote ranch, and the couple started a family. Frances gave birth to seven children in total, but three of the children died and were buried at the ranch. The Keys children grew up in frontier conditions. There was no plumbing, no electricity, and the nearest town was a two-day wagon ride away. Physically separated from much of the outside world, the family survived almost entirely on local resources.

The biggest challenge in the desert was securing a steady supply of water. Keys overcame this by damming a pond behind the ranch to create a small reservoir. He stocked the reservoir with fish and installed pipes that irrigated a small orchard and garden on the ranch. The family swam in the reservoir in the summer, and in the winter, when it froze, they organized ice skating parties.

Bill’s days were filled with hard physical labor. When he wasn’t mining or ranching, he was tending to the physical upkeep of his property. Frances spent her time gardening, cooking and tending to the animals on the ranch. The children were also responsible for a wide variety of chores. When they did have free time, the Keys children amused themselves with their imaginations. As one of them later recalled, “Our toys were usually pieces of iron or wood.”

Bill Keys was a born scavenger, a trait that served him well in the desert where basic goods were always in short supply. Over the course of his life, Keys claimed 35 local mine and mill sites, many of which were simply abandoned. Often he was less interested in the mine or the mill than in whatever machinery and spare parts he could scavenge from the property. His collection of odds and ends was legendary. Whenever local settlers needed tools or spare parts, they would always turn to Keys, who accepted cash but preferred trading for additional tools and spare parts.

Bill Keys got along well with most of his neighbors, but local tensions sometimes flared. Most disputes involved the desert’s limited resources, and most were settled far away from the eyes of the law. In 1929 Keys shot and wounded a local cowboy over a contested water well. Following the incident, Keys developed a mixed reputation in the region. Although many knew Keys as a fair and honest man, those who butted heads with him understood that his good nature had its breaking point.

About a decade after the incident at the well, Keys found himself involved in another feud. This one was with a retired Los Angeles Sheriff named Worth Bagley who moved to the region in the late 1930s. Although Bagley supposedly made the move for health reasons, in reality he had been discharged from the police force due to his repeated abuses of power and questionable sanity. Following his arrival in Joshua Tree, he developed a reputation as a loose cannon who was constantly armed and angry. It didn’t take long before his anger was directed at his nearest neighbor: Bill Keys.

Among other things, Bagley claimed that Keys’ “vicious” cattle were constantly bothering him. When Keys found some of his cattle shot, he blamed the killings on Bagley. Bagley responded by telling Keys, “You’ve accused me of shooting your cattle. Don’t never accuse me of that again or the next time I shoot, it won’t be cattle.”

The greatest point of contention between the two men involved a formerly public road that passed over part of Bagley’s property. Although Keys had used the road for years, Bagley told him, in no uncertain terms, that he was no longer allowed to use it. Keys ignored Bagley, and the two men grew so angry with one another that they stopped talking entirely. Before long Bagley was blocking the road with fallen Joshua trees and sprinkling it with broken glass.

On May 11, 1943, Keys was driving along the public section of Bagley’s road when he came upon a hand-drawn sign. “Keys,” the sign read, “this is my last warning. Stay off my property.” He looked up and saw Bagley approaching in the distance with a revolver. Keys grabbed his rifle but waited for Bagley to fire the first shot. Bagley fired and missed. Keys fired three shots in response. Bagley’s body fell to the ground.

Later that day, Keys drove to Twentynine Palms and notified the authorities that he had shot and killed Worth Bagley in self-defense. Seven weeks later, Keys was brought to trial. The prosecution argued that Keys had deliberately murdered Bagley, then tampered with the evidence. A doctor testified that Bagley had been shot while running away, thus invalidating Keys’ claim of self-defense. At the end of the trial, Keys was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 10 years in San Quentin Prison. He was 64 years old.

Following Keys’ conviction, his wife Frances devoted herself full-time to obtaining a pardon for her husband. But the family’s resources were limited, and Frances accomplished little on her own. In desperation she wrote to one of Bill’s old friends, a Ventura lawyer named Erle Stanley Gardner whom Keys had met when he came to the desert to camp in the late 1920s. Gardner went on to write a series of legal thrillers based on a fictional character named Perry Mason, and when the books became best-sellers Gardner used his celebrity to start a magazine column called “The Court of Last Resort.” The column featured case histories of potentially innocent men who might have been wrongly convicted. After Gardner presented the evidence, readers decided whether the case should be handed over to a panel of experts for further investigation. When Gardner received Frances’ letter, he immediately agreed to feature Keys’ case in “The Court of Last Resort.”

By the time the Gardner’s article appeared, Keys had already spent four years in San Quentin Prison. After the article was published, Gardner was flooded with letters demanding that the Keys case be reviewed. A team of volunteer experts reexamined the evidence, and they quickly concluded that Keys had been wrongly convicted. After presenting their findings to the state, Keys was granted a full pardon.

Five and a half years after Bill Keys entered prison, he walked out a free and vindicated man. He later referred to his time in prison as his “education” because he spent his days reading, catching up on current affairs, and learning how to play the guitar. Keys lived and worked at his Desert Queen Ranch for the rest of his life, becoming something of a local celebrity in his later years. His grizzled looks, checkered past, and friendly disposition gave him the aura of a Grandpa of the Old West. When Walt Disney Studios came to Joshua Tree in the 1960s to film The Wild Burro of the West, the director was so taken with Keys’ that he offered him a walk-on role as a grizzled old prospector.

In 1963 Frances Keys passed away and was buried at the Desert Queen Ranch. Six years later, Bill was laid to rest beside her. The couple had spent the better part of their lives in Joshua Tree, developing a bond with the surroundings that would probably never be surpassed by another white couple. It was in this stark landscape that Bill Keys carved out his own unique life, guided by his principles and rugged sense of identity.

As Bill’s son Willis later put it: “Dad was friendly and liked to get along with people, but had a lot of poor experiences with some people, and he wouldn’t let anyone run over him. He said, ‘Well, if the law won’t uphold me, I’ll uphold myself.’ And he did. He liked nature, and anybody that liked nature, he liked them. He liked the open country, and he liked fairness.”

Over the course of his life, Bill Keys watched the region around him change dramatically. In 1910, when he first arrived in Joshua Tree, the desert was still a remote and wild place. Although it had been discovered by white explorers several decades earlier, permanent white settlers were few and far between. Twentynine Palms was a cluster of shacks, the most advanced form of transportation was the mule-drawn wagon train, and the closest town was a two-day wagon ride away.

People drawn to this kind of environment were usually gold miners, cattle ranchers, or tuberculosis victims hoping the dry air would improve their health. But as the century progressed, this motley demographic began to change. Thanks in large part to air conditioning, the desert soon became the realm of ordinary, everyday people. By the end of the century, parts of the desert were among the fastest growing regions in California, with golf courses and strip malls claiming vast stretches of unlikely terrain.

The civilization—and later, suburbanization—of the desert traces its roots to a confluence of events in the early 1900s. When the century began, the population of Southern California was exploding. Railroads, which initially serviced only Northern California, now provided Southern California with a link to the population centers of the East. Thousands of people moved to Los Angeles in search of warm weather and cheap real estate. When the Panama Canal opened in 1914, Los Angeles became the busiest harbor on the West Coast, and the city’s economy boomed. The population of Los Angeles reached 1 million in 1920, then doubled over the following decade.

As Los Angeles boomed, city sprawl edged closer to the desert. At the same time, the city’s residents were unleashed by the introduction of the automobile. Suddenly, ordinary citizens had a safe, dependable way to explore the desert. Day trips became common, and newspapers published motorlogues filled with maps and detailed information.

But the desert’s newfound popularity soon caused unforeseen problems. In the 1920s a gardening fad for exotic desert plants developed in Los Angeles, and enterprising landscapers began making frequent trips to the desert and uprooting plants by the truckload. Their impact was swift and dramatic. A popular destination called Devil’s Garden, located just south of Joshua Tree, was filled with thousands of yucca and cacti at the turn of the century. By 1930 it had been stripped bare. Even today the plant life has yet to fully recover.

Other destructive trends were also taking place. Early desert travelers developed a habit of setting Joshua Trees on fire at night as a guide for other motorists. In 1930 the tallest known Joshua tree, which rose over 30 feet high, was set on fire and destroyed.

While some citizens were reveling in their conquest of the desert, others were growing alarmed. Among the most concerned was a wealthy Pasadena widow named Minerva Hoyt. An active gardener, Hoyt had become fascinated with the desert and its beautiful plants after moving to Southern California from Mississippi in the 1890s. Following the deaths of her husband and infant son, the desert became a source of solace to Hoyt. By the 1920s she was making frequent trips to the Joshua Tree region.

On her trips to the desert, Hoyt witnessed firsthand the ecological damage that was being done. Worried that the trend would continue, she took an active role in educating citizens about desert ecosystems. In 1927 she designed a desert conservation exhibit for the Garden Club of America’s flower show in New York City. The exhibit contained live cacti and stuffed animals in front of painted desert scenes, and it won the show’s gold medal. At the close of the show, Hoyt donated the plants to the New York Botanical Gardens “to be preserved as museum pieces and where it would reach the greatest number of school children to teach them to know and to love the plants that it is now so necessary to conserve.” She followed this up with a similar exhibit at the Royal Botanical Gardens in England two years later.

After returning from England, Hoyt was elected president of the newly organized Desert Conservation League. At the helm of this organization, she championed the creation of an extensive federal park in Southern California, encompassing parts of both the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts. She particularly liked the region just south of Twentynine Palms. But when Hoyt approached the National Park Service with her idea, she ran headfirst into a legal and bureaucratic nightmare. The boundaries outlined in her proposal were checkered with existing mining claims and plots of privately owned land. If a park was to be created, these properties would have to be purchased or accommodated. President Herbert Hoover, struggling with the Great Depression and already in a bitter land policy dispute with Congress, had little interest in tackling such a political powder keg. For the moment, Hoyt’s grand idea would have to wait.

In 1932 Franklin Roosevelt was elected President, and shortly thereafter he introduced the New Deal. It was a boon to the National Park Service. Public works projects were encouraged as a way to create jobs and stimulate the lackluster economy. New park proposals were welcomed, and Harold Ickes, Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Interior, supported a policy of setting aside land and working out the ownership problems later. Hoyt suddenly found herself with the perfect opportunity to promote a desert park. She re-pitched her proposal to the federal government, and this time it was well-received. In 1933 roughly one million acres of California desert were withdrawn from the public domain to be considered for National Monument status.

On August 10, 1936, Roosevelt signed a proclamation establishing Joshua Tree National Monument. The new monument contained 825,000 acres of land—less than Hoyt had wanted, but an impressive accomplishment nonetheless. Hoyt had originally proposed that the boundaries of the new park stretch all the way south to the Salton Sea, but the presence of the Los Angeles Metropolitan Aqueduct, which runs from the Colorado River to Los Angeles just south of the current park boundaries, prevented that from happening.

Hoyt had also hoped for national park status, not the slightly less protected national monument designation. But the park service concluded that the area lacked any “distinctive, superlative, outstanding feature that would give it sufficient national importance to justify its establishment as a national park.” The park service would ultimately reconsider its initial assessment, but for the moment the new national monument had larger problems to contend with.

Although Joshua Tree National Monument existed in name, its real estate remained somewhat questionable. When the monument was established, roughly 300,000 of its 825,000 acres were still privately owned. In fact, there was more private property lying within the boundaries of Joshua Tree than in the rest of the National Park Service’s holdings combined, with the exception of Hoover Dam. The majority of the privately owned land in Joshua Tree belonged to one owner: Southern Pacific Railroad. Keenly aware of the new value of its real estate holdings, the railroad stubbornly held out for the highest price.

Further complicating matters were the 8,000 existing mining claims located within the boundaries of the new monument. Although new claims were prohibited, existing mines still churned out vast quantities of gold, silver, copper, and iron ore. When the monument was established, mining companies were still extracting roughly 100 tons of ore from Joshua Tree each day. Although most mines operated in the remote eastern half of the monument, it was no secret that the government wanted those mines gone.

Over the next several decades the park service made small but effective strides in acquiring additional land. They patiently purchased real estate, negotiated trades, and scoured the fine print of existing deeds to find technicalities that invalidated the mining claims. In a shrewd administrative maneuver, construction of a private road system was delayed to discourage private development. Then, during World War II, the government banned all gold mining in the United States due to a shortage of labor and strategic materials. Mines in Joshua Tree sat idle for years, and many fell into severe disrepair. By the time the ban was lifted, some of the mines had become unprofitable to operate. Many were abandoned and reclaimed by the government. Slowly but surely, Joshua Tree National Monument started to take shape.

By 1950 the National Park Service had acquired enough real estate to turn Joshua Tree National Monument into a reality. But its existence was tenuous at best. A new generation of corporate prospectors, armed with new mining technologies, were eyeing the monument’s vast mineral resources. Mining interests lobbied hard to open up sections of Joshua Tree to mining or, better yet, do away with the monument entirely. Their campaign was so aggressive that some people worried the monument might actually be dissolved. To prevent that from happening, the park service decided to compromise.

In 1950 280,000 acres of Joshua Tree National Monument were returned to the public domain, which meant the land could be legally mined. For the park service, it was a reluctant transfer. But politically minded conservationists were determined to one day reclaim the land.

In 1964 Congress passed the Wilderness Act, which authorized the establishment of federally managed lands where mechanized vehicles and equipment were not permitted. Wilderness, according to the act, was an area “where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Twelve years after the act passed, roughly 80 percent of Joshua Tree National Monument was designated wilderness, providing an additional layer of protection. Around this time, a coalition of volunteers, legislators, and conservationists began discussing plans for sweeping legislation that would protect vast stretches of the California desert.

In 1986 California Senator Alan Cranston introduced a desert protection bill that would transfer several million acres of land to the National Park Service. It was hardly an easy sell. The bill ignited a fierce debate in Congress over the best way to protect California’s deserts, and the debate dragged on for years. By the time the act finally reached the U.S. Senate, three different Presidents had occupied the White House and Senator Cranston had been replaced by Dianne Feinstein. When the vote was finally held, the act squeaked through the Senate without a single vote to spare.

On October 31, 1994, President Bill Clinton signed the Desert Protection Act, which transferred 3 million acres of land to the National Park Service. Over 230,000 acres went to Joshua Tree, which was upgraded to national park status. The remaining land went to Death Valley (also upgraded to national park status) and the newly created Mojave National Preserve, which lay between Joshua Tree and Death Valley. Today the Desert Protection Act protects the largest park and wilderness area in the lower 48 states.

Today, Joshua Tree lures over one million visitors each year. Its rugged beauty, endless opportunities for outdoor recreation, and close proximity to the largest cities in the Southwest have all contributed to its popularity, which will undoubtedly help to protect it in the years to come.

No band will ever be as closely identified with the Joshua tree as U2. Their 1987 album, The Joshua Tree, is a rock masterpiece. It sold over 20 million copies and pretty much single-handedly made the band (and the trees) world famous. That four guys from Dublin could so brilliantly capture the mythology of the American desert is, frankly, a little disturbing. But our hats go off to them. Lyrics on The Joshua Tree are full of desert imagery—desert roses, desert skies, dust clouds, thunder storms—but strangely, Joshua trees are never mentioned. In fact, U2’s connection to Joshua Tree National Park is tenuous at best. The iconic Joshua tree on their album cover was actually located north of the park, closer to Death Valley. The band was originally going to call their album The Desert Songs or The Two Americas, until cover photographer Anton Corbjin told Bono about some strange plants he’d seen in the desert called Joshua trees. The next morning Bono came down with a bible and declared that the album had to be called The Joshua Tree. The group drove out to the desert, located a suitable tree, and shot the cover. Bono later admitted to a friend, “it was freezing and we had to take our coats off so it would at least look like a desert. That’s one of the reasons we look so grim.” Sadly, the lone Joshua tree featured on U2’s album cover has since toppled over. The location of the tree, off Route 190, is marked by rocks spelling out “U2” placed by devoted fans.

In 1973 the stolen corpse of country rocker Gram Parsons was smuggled into Joshua Tree National Monument and set on fire near Cap Rock. The events leading up to that incident have since become one of the classic legends of Rock n’ Roll.

Parsons was a southern-bred Harvard dropout who became one of Country Music’s bright young stars in the late 1960s. Many consider him to be the original alt-country crossover artist. Although his songs were country, he lived life like a rock star—flashy clothes, constant partying, heavy drinking and drug use. He became best friends with Keith Richards (Mick Jagger was reportedly extremely jealous of Gram), and the two often drove to Joshua Tree to get high, commune with nature, and scan the sky for UFOs. Before long, Gram was making regular trips to the desert.

On September 19, 1973, at the age of 26, Parsons died of a lethal combination of whiskey and morphine at the Joshua Tree Inn. His body was brought to Los Angeles to be flown back to Louisiana at the request of his stepfather, who wanted a private funeral without any of Gram’s friends. As Parson’s body rested in a morgue awaiting shipment, two of his friends got drunk and plotted to steal it. Parsons had once mentioned that he wanted his ashes spread in Joshua Tree, and his friends were determined to fulfill his wish. They borrowed a run-down hearse, drove to LAX, and intercepted the coffin before it was loaded onto the plane. Posing as undertakers, they convinced the airport to hand over Parson’s body. After their beer and Jack Daniels-filled hearse cleared airport security, they high-tailed it to Joshua Tree. When they reached a spot near Cap Rock Nature Trail, they unloaded the coffin, doused it with gasoline, and set it on fire.

In the years since Parson’s death, he has developed a strong cult following. His story has spawned a documentary, Fallen Angel, and an indie film, Grand Theft Parsons, starring Johnny Knoxville. For many years Gramfest, an annual tribute to the late rocker, was held in the town of Joshua Tree every fall.