CHAPTER 4

The Critics React

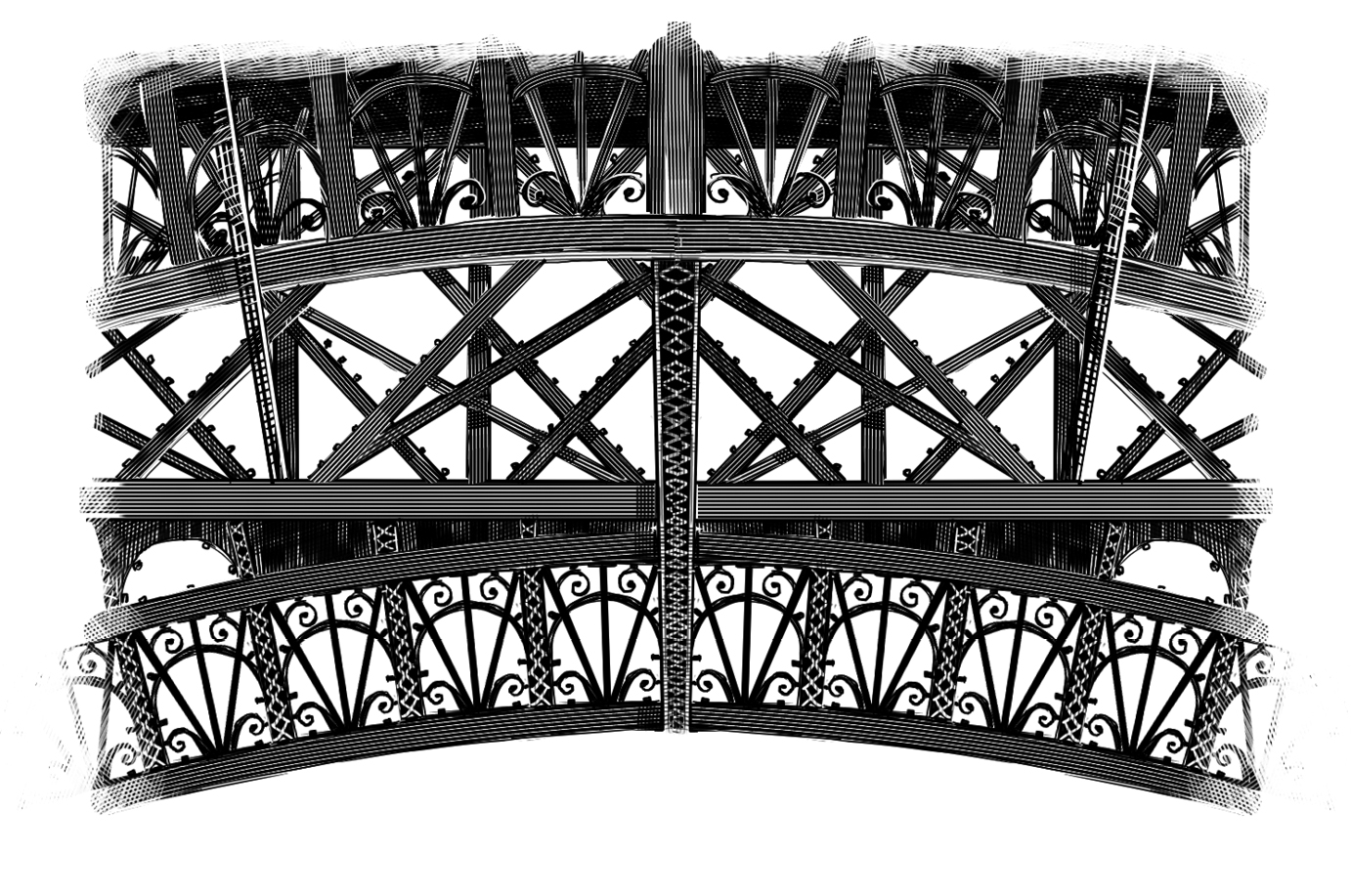

During the time the tower was constructed, buildings were growing taller all over the world. Big cities were running out of land. Tall buildings were the future. Wrought iron was the perfect material. It was easier to work with than stone.

The critics of the Eiffel Tower fumed. This was Paris, after all. A magnificent city built of beautiful stone.

No one protested as loudly as a group of painters, sculptors, architects, and writers. After seeing the plans for the tower, three hundred of them signed a protest against its construction. They called themselves the “Committee of Three Hundred,” named for the three-hundred-meter tower. Artists who signed included the composer Charles Gounod, the poet Paul Verlaine, the writer and playwright Alexandre Dumas Jr., and many others.

The protest was published in the Le Temps newspaper on February 14, 1887.

“Listen to our plea!

Imagine now a ridiculous tall tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black factory smokestack.”

Artists compared the tower to a streetlamp, a skeleton, and a factory pipe.

Guy de Maupassant

One of the most famous protestors was Guy de Maupassant, a writer who was well known for his short stories. He hated the tower so much that when it opened, he couldn’t bear to look at it. He decided to eat his lunch in one of the tower’s restaurants because that was the only place where he didn’t have to look at the tower itself. He later left France, saying he wanted to get away from the Eiffel Tower. He described it as, “This high and skinny pyramid of iron ladders, this giant ungainly skeleton upon a base that looks built to carry a colossal monument of Cyclops [a one-eyed monster], but which just peters out into a ridiculous thin shape like a factory chimney.”

Charles Garnier

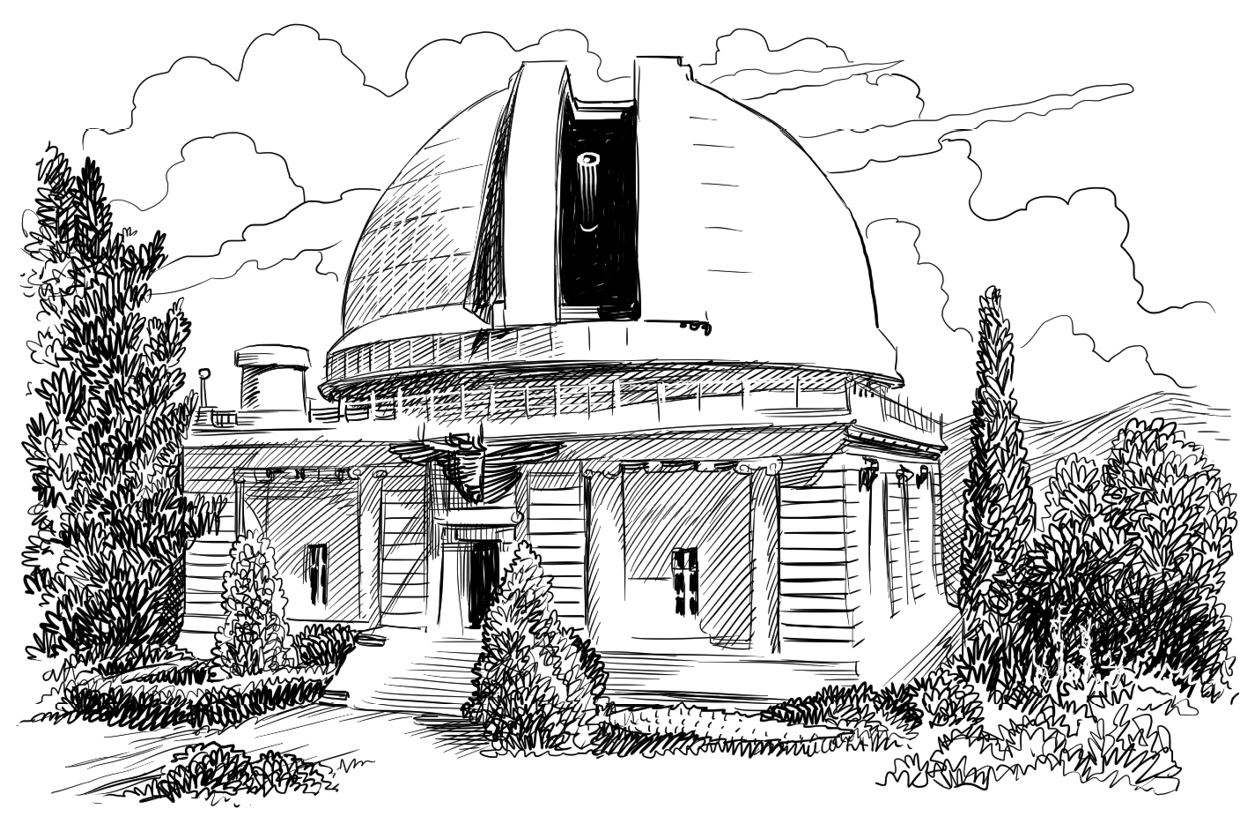

There was also Charles Garnier, one of the most talented architects in France. Ten years earlier, Gustave and Charles had worked together on a rotating dome for an observatory in Nice, France. Gustave called it his favorite project at the time. The two men liked each other. Now Charles was Gustave’s harshest critic.

The observatory in Nice, France

Charles Garnier had designed the Paris Opera House, one of the most glorious stone buildings in the city. Completed in 1875, it was called the Palais Garnier, or the Opéra Garnier, after the man who created it. Theatergoers arriving in horse-drawn carriages were greeted by statues and gargoyles on the outside and a world of luxury on the inside: staircases and statues made from different shades of the finest marble, and domed ceilings with gilded moldings and magnificent art.

Most Parisians considered it a lavish, glittering masterpiece.

Eiffel’s simple wrought-iron tower was as different from Garnier’s landmark as a candlestick from a chandelier.

Besides finding metal buildings ugly, Garnier was mad. The ridiculous tower was going to dwarf something he had designed for the fair. His Exposition of Human Habitation was located directly below the Eiffel Tower. It consisted of forty-nine different kinds of homes, from palaces to huts, to show how people around the world lived.

Exposition of Human Habitation

As Garnier continued to seethe about the tower, many other critics changed their minds. Once inside, they were able to study the artistic details of the lattice ironwork. They could stand at the top and take in the panoramic view of Paris. They noticed how the light moved in and out of the spaces between the girders. How could they have been so wrong? they wondered. Mr. Eiffel’s tower wasn’t a monstrosity at all. It was a brilliant work of art!