CHAPTER 6

The Fair Below

Down below, most of the exhibitions were finally up and running. More than 61,000 exhibitors displayed products and artwork, and performed music, dance, and theater. Although they came from all over the world, more than half of the exhibitors were from France or French colonies.

French Colonies

In 1889, France controlled many distant countries. Each was very different and had its own culture. This fair was their chance to show the world how they ate, dressed, and lived.

The French colonial expositions were located in the Esplanade des Invalides, up the river from the Eiffel Tower. Visitors were given a ticket called the “magic carpet” that allowed them to experience cultures from all over the world.

Actors from Indochina, now called Vietnam, put on a show. Dancers from Java performed native dances. Workers and performers lived in villages with houses like the ones in distant Tahiti and Senegal.

But the 1889 fair was not just about the French and their colonies. Beautiful tiles adorned a Tunisian palace. Algerians were at work, embroidering slippers and weaving baskets. Egyptian donkeys pulled carts. There was even a working English dairy where cows gave fresh milk. Visitors could watch Devonshire cream being made and eat delicious homemade ice cream at small tables.

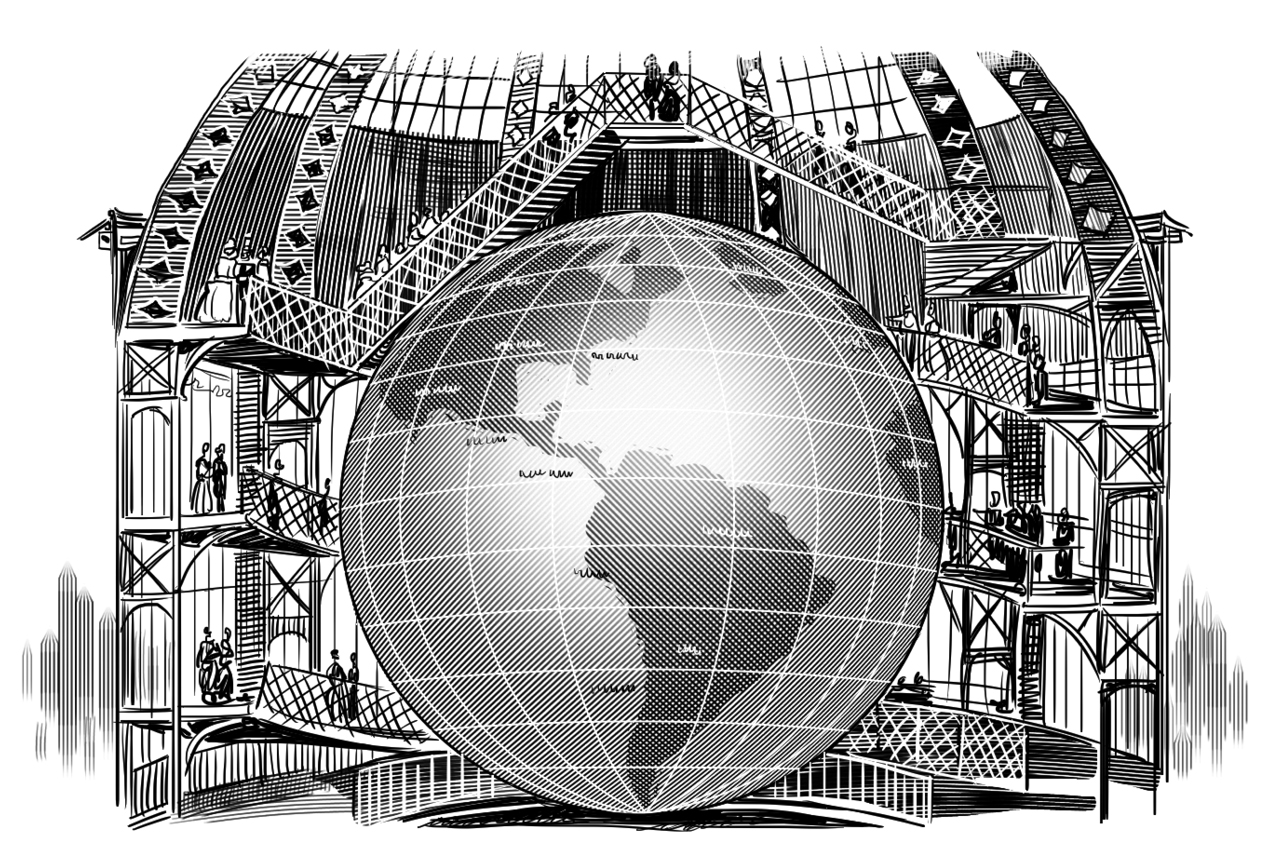

One of the most admired exhibitions was a huge model of the earth, accurately scaled to size. With a diameter of forty-two feet, it was exactly one-millionth the size of the earth. Like the fair itself, this rotating globe was meant to introduce visitors to the world as a whole. Perfectly measured countries, cities, bodies of water, mountains, shipping routes, telegraph lines, and a variety of geographical facts were painted on the outside.

Visitors were especially excited to see the American exhibits. Thomas Edison’s electric lights glittered everywhere. Otis elevators carried passengers to the top of the Eiffel Tower. Now visitors could learn about American culture as well. They could view the newest art from the 255 American painters exhibiting at the fair. Many were especially excited to see the much-talked-about portraits by John Singer Sargent, who would win a medal of honor at the medal ceremony on September 29.

And everyone wanted to try out the telephone display! Alexander Graham Bell had invented the telephone thirteen years earlier, but long-distance calling was still in the future. People wondered what it would sound like. Inside the exhibit, visitors found a line of telephones on one wall. Miles away, at the Paris Opera House, telephone receivers were broadcasting live music. The concert could be heard through the phones, all the way across the city. It was incredible!

But everyone, it seemed, couldn’t wait to see Thomas Edison’s newest inventions. His exhibit was inside the beautiful fifteen-acre glass-and-steel Gallery of Machines. Hurrying into the gallery, visitors were surrounded by electric lights that blinked, buzzed, and fizzled. Pumps shuddered and thumped. Engines pounded and clanked.

Some people stopped to inspect the new machines, but most rushed to try out Edison’s phonograph. Earphones were passed from visitor to visitor. Each person was allowed three minutes to listen to the national anthems of France and the United States.

But America didn’t just bring inventions and art. They also brought Buffalo Bill and Annie Oakley. On the other side of the river, beyond the Louvre Museum, Buffalo Bill Cody was putting on his very popular Wild West show.

During the 1800s, Americans had been moving west. Before the first cross-country railroad was completed in 1869, pioneers traveled in covered wagons. Many American Indian tribes hunted buffalo. Mail was delivered by the Pony Express, on horseback or in wagons. The western plains were wild and dangerous.

In a Paris amphitheater, Buffalo Bill’s touring show re-created the Wild West—or at least the Wild West as white Americans liked to picture it.

Plains Indians riding bareback did battle with Pony Express messengers. Led by Buffalo Bill, cowboys on horseback shouted and raised their rifles as they raced to save the passengers on the wagon train. Annie Oakley, the show’s world-famous five-foot-tall sharpshooter, demonstrated why she was known as “Little Sure Shot.” She was able to shoot a cigar out of her husband’s mouth!

That night, as visitors on both sides of the Seine left the fairground, they stopped and looked up. The tower was blazing with light. The spotlight was spinning colors through the sky. The fountains below it were dancing.

In September, officials agreed to keep the fair open for an extra week. It would close exactly three months after it opened. The 1889 Exposition Universelle had been a huge success.