Chapter 9

Revering the Role of Religious Leadership

In This Chapter

Finding out what priests, swamis, and gurus do

Finding out what priests, swamis, and gurus do

Studying the characteristics of great Hindu leaders

Studying the characteristics of great Hindu leaders

Learning the impact of saints and sages on Hindu philosophy

Learning the impact of saints and sages on Hindu philosophy

What is the path?

In the Mahabharata, a Hindu epic that I discuss in Chapter 12, a Yaksha (nature spirit) dwelling in a forest posed that question to Yudhishtira to probe his spiritual strength. The question really means: How should one lead a life on earth? How does one lead a spiritual life? How does one attain salvation? Yudhishtira replied simply:

What great men have followed — THAT is the path.

The reply bypasses the complexities of scriptures, competing philosophies, and ritualistic approaches. A simpler route is to observe the life led by a great person, accept to learn from and follow that exemplary person, and thus seek the path toward knowledge and salvation. Who are such great men (or women)? They could be kings, warriors, or learned men or women, but in this context they’re holy persons whose guidance and grace are sought for such an important quest.

Legend after legend from ancient India portrays kings and emperors rushing down from their thrones to greet and offer obeisance to a guest clad in saffron — a holy man. (The color saffron is associated with sacrifice and renunciation.) Centuries later, this practice continues with Indian presidents and prime ministers showing respect to religious leaders, occasionally conferring with them and seeking their counsel. Even in the United States today, it is not uncommon for a community of Hindus to show special respect to these visiting gurus and swamis in saffron robes.

This chapter introduces you to the centuries-old Hindu tradition of revering saints, swamis, and gurus. I define what each of these words means to a Hindu and list some of the great men who are considered saints, swamis, and gurus. Also, Hindu families look to religious teachers for guidance on how to learn and practice the faith and have special relationships with these teachers, who are more accurately called preceptors. I explain what this word means and why the relationship between student and teacher is so vital to Hindus.

Priests, Gurus, and Swamis: Spiritual Leaders of Hinduism

Within a Hindu community, different people have different interests related to their religion. Therefore, each person’s relationship with his or her religious leader is unique. Here are just a few examples of the types of interaction between Hindus and their religious leaders:

Hindu intellectuals may seek the guidance of seers (mystics) and philosophers, and some intellectuals may choose to attend discourses (lectures) and contribute to discussions and journals focused on religious topics.

Hindu intellectuals may seek the guidance of seers (mystics) and philosophers, and some intellectuals may choose to attend discourses (lectures) and contribute to discussions and journals focused on religious topics.

Other Hindus may prefer to visit a swami or guru (teacher) and may support that leader with cash or in-kind contributions.

Other Hindus may prefer to visit a swami or guru (teacher) and may support that leader with cash or in-kind contributions.

Some Hindus find fulfillment worshipping at a temple, participating in and helping with daily or weekly services.

Some Hindus find fulfillment worshipping at a temple, participating in and helping with daily or weekly services.

Others obtain peace by joining a group that conducts daily or weekly programs in which a leader, knowledgeable in Hindu devotional songs, leads the group in singing such songs accompanied by musical instruments.

Others obtain peace by joining a group that conducts daily or weekly programs in which a leader, knowledgeable in Hindu devotional songs, leads the group in singing such songs accompanied by musical instruments.

Some Hindus may associate themselves with a yoga center (where physical exercises and meditation techniques are taught) and visit it when the founder or the leader addresses the disciples and daily visitors.

Some Hindus may associate themselves with a yoga center (where physical exercises and meditation techniques are taught) and visit it when the founder or the leader addresses the disciples and daily visitors.

Others are completely satisfied simply consulting a priest for advice regarding an upcoming wedding or domestic ceremony (such as a naming ceremony for a baby).

Others are completely satisfied simply consulting a priest for advice regarding an upcoming wedding or domestic ceremony (such as a naming ceremony for a baby).

To meet the variety of needs, a corresponding cadre of religious leaders has sprung up over time. Chief among them are priests, swamis, and gurus. The following sections describe who these key religious leaders in Hinduism are, explain how one becomes such a religious leader, and identify the more renowned leaders.

Priests: Leading services in temples and serving the community

Priests are usually from the brahmin caste (refer to Chapter 5) and are trained in agamas: procedures involved in temple rituals and domestic rituals. More often than not, priests learn how to conduct rituals from a father or uncle. Some also get formal schooling in Sanskrit and scriptures. Priests are almost always employed by temples.

Hindu priests are known as pujaris or purohits. Their main function is to perform daily and weekly services to temple deities with or without the presence of devotees. In addition, they must keep the sanctums (the holiest spaces in the temple where the deities reside) clean and stocked with materials needed for performing the puja (worship).

Many priests become family priests, which means they guide and lead families during major ceremonies such as weddings and housewarmings. In such situations, a rapport and mutually supportive relationship develops between the priest and the family. For this reason, priests are also an indispensable part of a Hindu community.

Swamis and gurus: Training and inspiring young people

Swamis are spiritual leaders who teach, train, and guide others not only by delivering sermons, discourses, and lectures but also on a one-on-one basis. If a swami belongs to an order, such as the Ramakrishna Order, he serves that order as an authorized, ordained swami who is part of a global organization, and he is governed by rules, regulations, and guidelines set up by the parent organization. Swamis may or may not be attached to a temple, and they may have their own ashrams/centers of learning, as I explain later in this section.

Understanding the concept of master and disciple

Having this book in your hands now means you are interested in religion — in particular, Hinduism. Suppose you were interested in more in-depth information about Hinduism; you’d read advanced treatises on the subject and deepen your understanding of basic concepts. But if your interests were to run even deeper — if you wanted to be spiritually illumined, in other words — then, to follow the Hindu approach, you would have to go beyond books.

Establishing ashrams

A swami or guru needs a space in which to teach his disciplines. Such a space may be an ashram: a hermitage (secluded space) often located far from populated areas. (Think park-like locations, such as forests, river banks, and hills.) It usually has residential facilities for students and visitors. At ashrams of the ancient past, the students (children from nearby communities) lived an austere life with the guru and sometimes his family. They served the guru and obtained a disciplined and rigorous training in the faith.

Starting in the 1960s, several swamis who settled in the United States from India established ashrams and took Western and Hindu disciples. Several such thriving ashrams can be found in the United States today. Ashrams in the United States are often called religious centers. More often than not, they offer programs in yoga, meditation, and Ayurveda (the traditional medicine of ancient Hindus, which defines the health of a human being based on the extent of balance among three principal components: the body components, the extent of lubrication of joints, and digestive ability).

Studying at an ashram

At ashrams, the swamis have strict daily routines for the disciples, for themselves, and for visitors. Training takes place with rigor and vigor appropriate to the level of the trainees. Gurus may conduct classes devoted to topics selected from scriptures and are available to answer questions of a spiritual and theological nature.

Keep in mind that studying and staying at an ashram, paying for classes, or volunteering do not require conversion to Hinduism.

For serious disciples, training also includes Sanskrit, Hindu scriptures and philosophy, and Hatha yoga (which emphasizes physical exercise). A disciple may have the goal of being ordained as a monk into the same Hindu order that the swami belongs to, and he may wish to stay with and serve the swami and the ashram (living a monastic life). Such followers perform assigned tasks, including teaching.

In the upcoming section “Initiating Hindu monks,” you find out more about how one becomes a Hindu monk. First, I introduce you to four Hindu religious centers in the United States so you can get a sense of their variety.

Yogaville (Buckingham, Virginia)

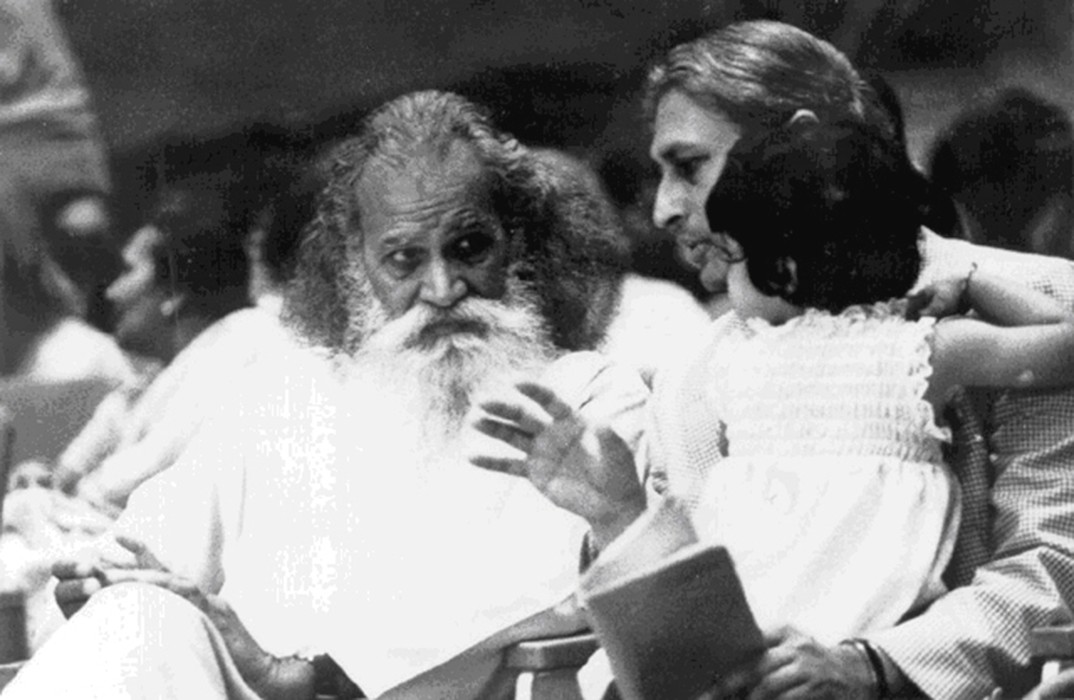

Satchidananda Ashram, also known as Yogaville, was founded in 1980 by Swami Satchidananda (1914–2002), who is shown in Figure 9-1.

Figure 9-1: Swami Satchida-nanda with the author at the Hindu Temple in Connecticut, 1989.

Originally established in a quiet corner of Connecticut, the ashram moved to a 500-acre plot of land on the James River in Virginia. A beautiful interfaith temple in the shape of a lotus was also built; it’s known as Light of Truth Universal Shrine (LOTUS). Swami Satchidananda’s Integral Yoga approach (a combination of physical, mental, and spiritual practices) is an attempt to synthesize all the Yogas (see Chapter 21) toward development of the body, mind, and soul.

A man of extraordinary simplicity, full of charm and grace, Swamiji mended many lives. He took many youths under his wing and brought them back to a path free of drugs and alcohol. Many of his disciples around the world continue his legacy, bringing honor to a great man of peace. For more information about the center, visit www.yogaville.org.

Hindu Monastery (Kauai, Hawaii)

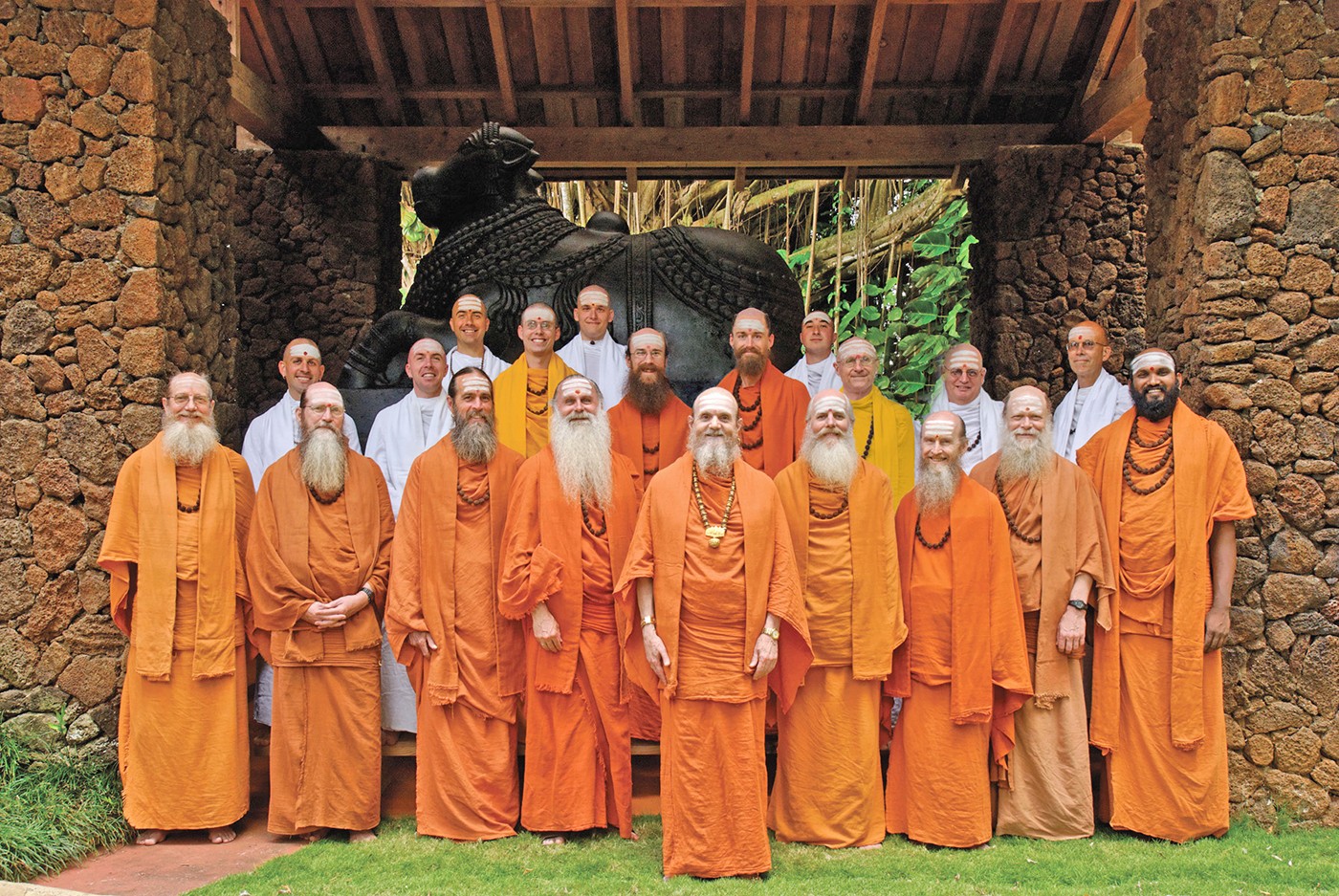

Another organization doing yeoman service to young people is the Hindu monastery on a beautiful 353-acre property in Kauai, Hawaii. The emphasis here is Shaiva Siddhanta, which means Shaivite traditions (see Chapter 4) that are practiced in South India and Sri Lanka. The disciples do not study the Bhagavad Gita. The monastery publishes a high caliber journal known as Hinduism Today.

Only single Hindu men (or converts to Hinduism) under the age of 25 are eligible for monastic training at this center. An impressive order of monks (see Figure 9-2) have dedicated themselves to a monastic life offering regular programs of instruction and training. This monastery is currently under the leadership of Satguru Bodhinatha Veylan Swami. For more information about the monastery, visit www.himalayanacademy.com/ssc/Hawaii.

Figure 9-2: Monks at the Hindu Monastery in Hawaii.

Arsha Vidya Gurukulam (Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania)

This gurukulam (which means “residential center under a guru”) focuses on teaching Vedic scriptures through regular program offerings on its campus, as well as online. Under the leadership of Swami Dayananda Saraswati, the gurukulam has an excellent staff that includes additional ordained monks. Two temples and a bookstore allow for training in chanting and learning the basics of Hindu philosophy. Visit www.arshavidya.org to find out more.

Maharishi University of Management (Fairfield, Iowa)

The Maharishi University of Management is a fully accredited university founded by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in 1971. The university’s uniqueness is its emphasis on developing a knowledge of one’s own self as a basis for all studies. Transcendental Meditation is part of each student’s life. Students may earn basic and advanced degrees in traditional subjects, as well as degrees in Vedic Science. Visit mum.edu to find out more.

Initiating Hindu monks

Some ashrams are monasteries; they are specifically concerned with the training and ordination of young men for a celibate life as monks. These ashrams are usually run by recognized orders.

A serious aspirant can be initiated into an order of Hindu monks if the student is prepared and the guru blesses it. Preparation may differ from one order to another, but the fundamentals remain the same. In general (there are exceptions), a knowledge of the Vedas and the Bhagavad Gita (sacred texts that I explain in Part III) and an extraordinary commitment to serve human beings anywhere at any time irrespective of any other consideration are minimum requirements. Above all, the blessing of the guru is essential.

To become a monk, a student is initiated into sanyas, which means “renunciation.” The student takes part in procedures and ceremonies that are held in the open and under the direction of the authorized head of the order of monks. Upon initiation, the individual’s life is dedicated only and entirely to the service of others.

After ordination, the monks sometimes continue as residents of the monastery. Sometimes, in India, they may become wandering mendicants (those who live essentially on alms, giving an opportunity for the donors to gain spiritual merit).

Several U.S. and European centers offer disciples the opportunity to be initiated into sanyas. The Hindu Monastery in Kauai is one example.

What It Takes to Become a Spiritual Leader

Concern for the welfare of humanity, extraordinary interest in personal salvation, and a general disinterest in material life are the primary drivers that influence an individual to first seek a spiritual leader who can guide the aspirant to be a good disciple. If the apprenticeship works out, the disciple may advance to a higher state of renunciation, totally absorbed in self through deep meditative states and devoted to learning and service. The guru — and only the guru — can decide the future of the disciple and bless him with a mission to lead others. Thus, a new leader is born.

In the case of almost every Hindu spiritual leader, what stands out is the leader’s intense desire to know God. To realize that desire, spiritual leaders exhibit the following characteristics or actions:

They have acquired spiritual wisdom through penance. (See the next section for an explanation of penance.)

They have acquired spiritual wisdom through penance. (See the next section for an explanation of penance.)

They have risen above worldly life; a sense of detachment is evident.

They have risen above worldly life; a sense of detachment is evident.

They have extraordinary love for humanity and creatures.

They have extraordinary love for humanity and creatures.

They exhibit qualities of fearlessness, confidence, and a balanced mind.

They exhibit qualities of fearlessness, confidence, and a balanced mind.

They lead a chaste life. In each category of spiritual leaders, you will find most are unmarried, although some may have families.

They lead a chaste life. In each category of spiritual leaders, you will find most are unmarried, although some may have families.

They exhibit extraordinary self-control. The best of Hindu monks have always kept the mind and the body finely tuned with the constant practice of yoga, meditation, and the study of scriptures.

They exhibit extraordinary self-control. The best of Hindu monks have always kept the mind and the body finely tuned with the constant practice of yoga, meditation, and the study of scriptures.

They are dedicated to the concept of Truth in everything they do.

They are dedicated to the concept of Truth in everything they do.

A Sanskrit verse sums up the personality of the masters:

Hard as diamond and soft as a flower

Who can know the mind of the great?

Meaning? Spiritual leaders are hard as diamonds when it concerns studies and training and soft as flowers in relations with other souls.

So how do people attain this state? Through penance and renunciation. The following sections explain these concepts.

Probing the idea of penance

The Hindu concept of penance encompasses dedication, study, service, apprenticeship under a guru, practicing austerities prescribed by the teacher, and training the mind to concentrate. Through these actions, an aspirant attains the state necessary to become a spiritual leader. See my detailed discussion of Raja Yoga in Chapter 21 to find out much more.

Looking at the concept of renunciation

Individuals who long for a spiritual life have little interest in what others would call normal life. They don’t hate normalcy; they just don’t feel its pull. They are, in a manner of speaking, above it. Setting up a household doesn’t interest them. They choose to remain celibate and direct their energy at examining deeper aspects of life and death. They are renunciates: They engage in meditation, breath control, and yogic postures, and they eat frugal vegetarian meals. Their primary goals are the following:

Seeking personal salvation: Normally the focus of renunciates is personal salvation. They realize that they are born in this world and bliss comes from striving to reach back to Brahman and end the cycle of births and rebirths. As such, they prefer to keep to themselves, and they may not be accessible to anyone. Although you may get the impression that renunciates don’t care about this world, that is only partly true. They know they’re part of this world, but their interest is seeking Truth. Therefore, all their activities are oriented toward that single goal.

Seeking personal salvation: Normally the focus of renunciates is personal salvation. They realize that they are born in this world and bliss comes from striving to reach back to Brahman and end the cycle of births and rebirths. As such, they prefer to keep to themselves, and they may not be accessible to anyone. Although you may get the impression that renunciates don’t care about this world, that is only partly true. They know they’re part of this world, but their interest is seeking Truth. Therefore, all their activities are oriented toward that single goal.

Serving humankind: A guru may direct renunciates to take on a spiritual task in the so-called “real world.” Such an assignment brings the future leader into contact with people at large in big cities. Depending upon the guru’s domain of interest and/or influence, he may (either at the request of a community or on his own) decide to send one of his disciples to a town, city, or village to set up a center to serve people. The new center serves the specific needs of the community (education, drug rehabilitation, caring for the sick and the elderly, and so on), and the renunciate is part of the community as a religious leader. The choice of who goes where is entirely up to the guru.

Serving humankind: A guru may direct renunciates to take on a spiritual task in the so-called “real world.” Such an assignment brings the future leader into contact with people at large in big cities. Depending upon the guru’s domain of interest and/or influence, he may (either at the request of a community or on his own) decide to send one of his disciples to a town, city, or village to set up a center to serve people. The new center serves the specific needs of the community (education, drug rehabilitation, caring for the sick and the elderly, and so on), and the renunciate is part of the community as a religious leader. The choice of who goes where is entirely up to the guru.

Mythological and Ancient Saints

There are religious leaders, and then there are religious leaders. Some leaders with extraordinary knowledge, analytical skills to delve deep into scriptures, and a magnetic personality, attract disciples of high caliber. They have all the characteristics of spiritual leaders mentioned in the previous section, and more. Such gifted and inspired individuals came along in ancient and modern India, and their contributions have changed thousands of lives and unraveled the mysteries of many a scripture. They effected reformations and insights that refreshed and validated Hindu thought over millennia. The result is a dynamic religion that has never ceased to satisfy a wide range of believers.

Ancient sages (wise persons) were known as rishis (pronounced rushis). The rishis are the most revered of all the spiritual leaders mentioned in Hindu legends, epics, and puranas.

Legend has it that these ancient sages were revered by either their own peers or by royalty and were recognized with special titles. These designations have come down to us and are acknowledged as such through stories notably in the Hindu epics. The special titles are the following:

Deva rishi: A sage honored by gods, or god-like

Deva rishi: A sage honored by gods, or god-like

Brahma rishi: One who has realized Brahman

Brahma rishi: One who has realized Brahman

Raja rishi: A king with spiritual wisdom

Raja rishi: A king with spiritual wisdom

Maha rishi: A great sage

Maha rishi: A great sage

Param rishi: A sage who has realized God (Paramatman)

Param rishi: A sage who has realized God (Paramatman)

Shruta rishi: A famous sage

Shruta rishi: A famous sage

Kanda rishi: A sage who has heard by revelation a section of the Vedas

Kanda rishi: A sage who has heard by revelation a section of the Vedas

Any of these rishis may be honored with the title or description of saint. This title is honorific and not attached to any system of canonization.

Among the legendary rishis, a few made indelible marks on ancient societies and played major roles in Hindu stories, such as Puranas and epics. These rishis influenced events and helped restore dharma (moral order or balance; see Chapter 1). I introduce you to some of them in the following sections.

The Seven Sages

Hindu mythology refers to the Seven Sages (Saptarshis or Sapta Rishis) who are eternal, much like the Vedas, and are preserved at the end of each cycle of time. (As I explain in Chapter 1, Hindus believe that time is cyclical; at the end of the last eon, all of creation is destroyed so it can be reborn. But the Vedas are preserved, always.) These sages are often known by the following personal names: Bhrigu, Angirasa, Atri, Vishvamitra, Kashyapa, Vasishta, and Agastya. (Some scholars suggest other names: Jamadagni, Bharadvaja, Gautama, Atri, Vasishta, Kashyapa, and Vishvamitra.)

The Seven Sages are believed to be represented in the seven brightest stars in the constellation Ursa Major. They are considered eternal, immortal guardians of dharma, and their task is to teach the Vedas to the new world after each cosmic recreation.

Narada

Narada muni is a familiar sage in the sacred mythological literature of Hindus. (Muni is another name for a sage.) Considered a one-man postal service, Narada traveled a great deal and collected information, which he freely disseminated. His efforts caused rivalries and fights but occasionally had life-changing effects. Hindus refer to him humorously as a gossiper extraordinaire! Narada was a sage nevertheless and kept good company, visiting the gods Vishnu, Shiva, and Brahma frequently, collecting information from them and conveying it to them. Called a deva rishi (divine sage), Narada traveled the universe preaching dharma, motivating people to have bhakti (love of God), visiting kingdoms, and sharing information among and about friends and rivals.

The Darshana philosophers

We know the names of six ancient philosophers who helped develop sophisticated approaches to seeing reality in the Hindu context: Gautama, Kapila, Jaimini, Badarayana, Patanjali, and Kanada. (By “ancient,” I mean they lived perhaps 1,500 to 2,500 years ago.) But other than their names, we don’t know much about them. What little we do know comes courtesy of commentaries on these philosophers’ complicated ideas, which were written some centuries later. I write about these philosophers in Chapter 19.

More Recent Saints

In this section, I introduce you to principal saints whose more recent contributions to Hindu philosophy are recognized by scholars and laymen alike. (By “more recent,” I mean within the past 1,200 years or so. Remember that the Hindu religion has been around for a very, very long time!)

The acharyas

The spiritual leaders in this section are known as acharyas (“great leaders”). They argued about the nature of the relationship between individual souls and the Supreme Soul and helped found the Hindu denominations that I describe in Chapter 4.

Here I introduce you to Shankara, the founder of Advaita (Nondualism); Ramanuja, the founder of Vishistadvaita (Qualified Nondualism); and Madhva, the proponent of Dvaitha (Dualism). Keep reading to find out a bit about each acharya and his philosophy.

Shankara (788–820 CE)

Very little is known about Shankara’s personal life. Even his year of birth is in doubt, with dates varying between 508 BCE and 788 CE. (The latter date is the one most scholars seem to agree upon.) He was born at Kaladi, a town in the present-day Indian state of Kerala. It is said that by the age of 10, he had already mastered the Vedas and was engaging scholars in debate and discourse. He was a prolific writer and the founding father of the philosophy known as Advaita: Nondualism.

I explain this philosophy in Chapter 20, but here’s the abbreviated version: Advaita emphasizes that there is only one Reality, which is Brahman. Brahman (the Supreme Self) and the individual atman (soul) are one.

Although Shankara and his followers worshipped Shiva and forms of Vishnu (leading to a denomination known as Smartism; see Chapter 4), the focus of Advaita is jnana (spiritual knowledge). This knowledge removes the individual’s ignorance pertaining to his or her individual soul’s true identity with the Supreme Soul.

In his short life (he lived only 32 years), Shankara fought to restore Hinduism on the basis of the Vedas by countering what he saw as a decline of spirituality and an emphasis on materialism. Referred to as Adi Shankara (“the first Shankara”), this reformer toured India from north to south and established four major centers, known as maths, to teach Advaita. The centers are: Badrinath in the north, Puri in the east, Shringeri in the south, and Dwaraka in the west. To this day, these four centers are managed by acharyas referred to as Jagadguru Shankaracharya. The first part of that name, Jagadguru, means “preceptor (teacher) of the universe.” The second part identifies the acharyas as spiritual descendents of Adi Shankara.

Ramanuja (c. 1017–1137 CE)

Ramanuja, popularly known as Sri Ramanujacharya, was born in Sri-Perumbudur in the southern state of Tamilnadu in the year 1017. He studied Vedanta (a topic I cover in Chapter 20) and became the chief proponent of a philosophy similar to Shankara’s but with a qualification. This philosophy became known as Vishishtadvaita, or Qualified Nondualism. The emphasis in this approach is to balance the need for spiritual wisdom with passionate devotion to God through surrender.

A devotee of Vishnu, Ramanuja wanted his followers to experience the bliss of God’s love. His reasoning was that this relationship was possible only if the individual remained distinct from Brahman. According to Ramanuja, total identity of the individual with Brahman dilutes what could otherwise be a beautiful, loving dependence. (Dependence requires two; when that distinction is lost — when you become one with Brahman — the dependence is lost as well.)

Ramanuja’s intention was to merge reason with faith. Therefore, while accepting Shankara’s insistence that Brahman is Reality, he reasoned that it was not the only reality. Instead, he allowed for the relative realities of individual souls and matter.

Ramanuja developed a following when he settled down at Srirangam in Tamilnadu and led the SriVaishnava movement, which became and continues to be an important Hindu denomination (see Chapter 4). Later he moved to Melkote in the state of Mysore (now in Karnataka) and established a famous shrine for Cheluva Narayana (a form of Vishnu). You can find out more about this shrine in Chapter 16.

Madhva (c. 1199–1278 CE)

Madhva was a Vaishnava theologian born near Udupi in the present state of Karnataka. At school, he proved to be more an athlete than a scholar. He excelled in sports activities and left school to study Hindu scriptures at home. During this period, he developed an intense desire for a monastic life.

At 25, he took vows of renunciation and devoted himself to advanced studies of Shankara’s Nondualism (the Advaita Vedanta philosophy). Soon after, he developed his own approach to Vedanta, interpreting it in a different light than did Shankara and Ramanuja. Madhva maintained that the individual self and the Supreme Self are indeed distinct. This doctrine of difference, known as Dvaita (Dualism), emphasizes differences between (1) the Supreme Self and an individual self, (2) all the individual selves, (3) the Supreme Self and matter, (4) the individual self and matter, and (5) one substance and another. This last item in the five differences appears obvious, but it is quite a subtle concept. Nine substances are included in this concept: earth, water, light, air, ether, time, space, soul, and mind. I discuss the impact of this view in relation to the Hindu view of reality in Chapter 19.

Madhva interpreted liberation to mean experiencing the bliss of the Lord through surrender to a deity. The famous Udupi Krishna shrine in the western Karnataka town of Udupi is testimony to this devotion.

Nineteenth-century saints

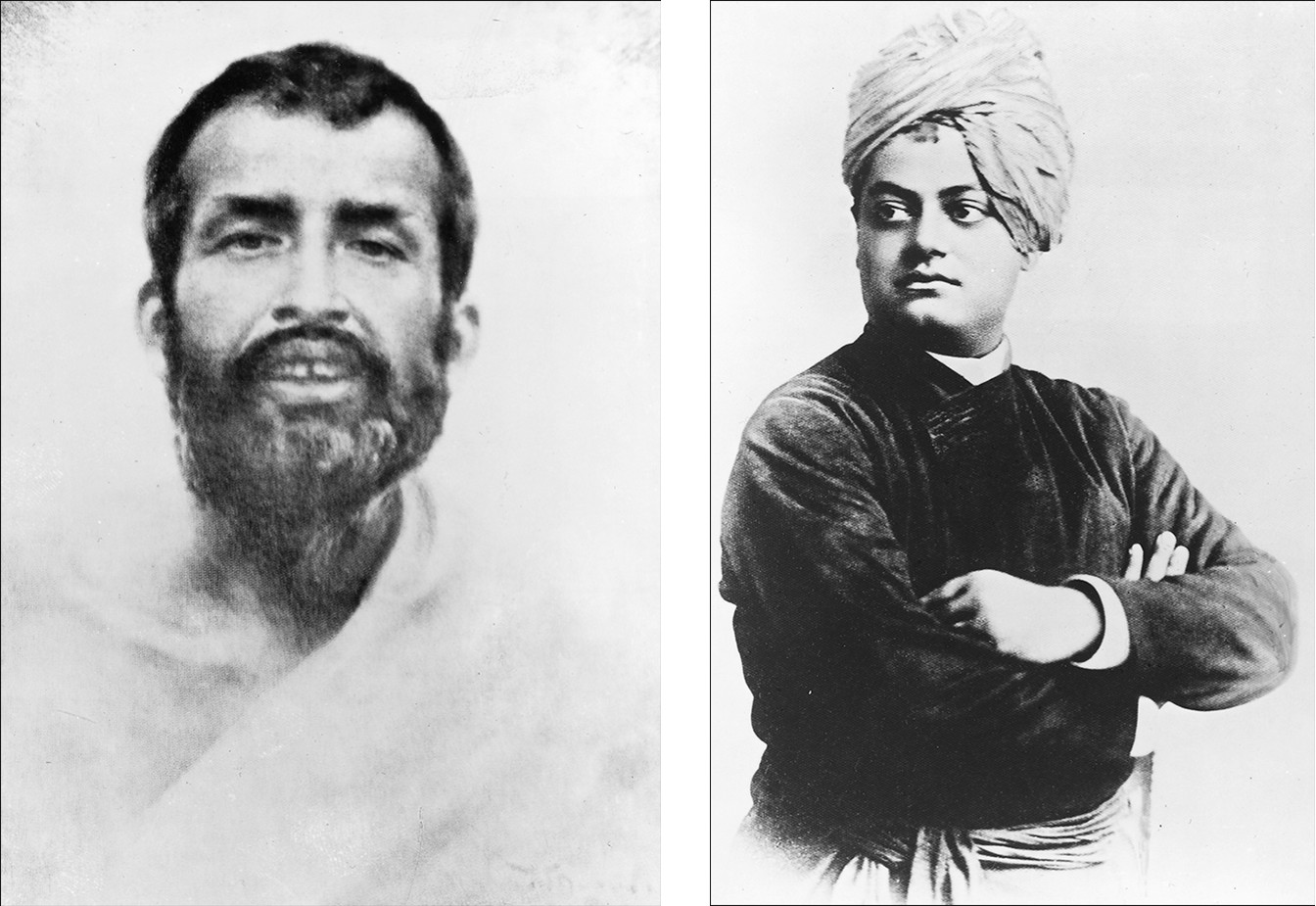

Much closer to our own time, several nineteenth-century philosophers, monks, and preachers were able to sort out the different philosophies and condense them so that they could be taught and learned by thousands. Because of their efforts, the world is full of well-established and active monastic orders that offer instruction and train Hindu monks in a systematic manner. The following sections focus on four such saints: Ramakrishna and Vivekananda, shown in Figure 9-3; Shivananda; and Ramana Maharshi.

Figure 9-3: Rama-krishna (left) and Vive-kananda (right).

Ramakrishna (1836–1886)

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa was an extraordinary saint of the nineteenth century. He served as a priest at the famous Kali temple at Dakshineshwar near Kolkata (Calcutta). His goal was to see God, be with God, and serve God. He had no other interests. He was a poster child of the devotional approach, surrendering himself to Mother Kali’s image, worshipping her, begging and weeping and longing to actually see her in person.

As a boy, he showed little interest in school. At the sight of anything divine, he easily lost himself in deep meditation. He sought solitary places to think and meditate, and he stayed in that state for hours. In his teens, he frequently considered becoming a monk, but he rejected the idea as selfishness. He preferred to work to benefit mankind.

His knowledge, devotion, and rigorous practice attracted young men who sought his advice on spiritual matters, and in this way, Ramakrishna laid the foundation of modern Hinduism — unintentionally! Those drawn to him soon became his disciples. His wife, Sharada Devi, became his disciple, serving him and his other disciples. Many famous people began to take notice of this extraordinary Hindu saint. Word got out, and seeds were sown for what would become the now-famous Ramakrishna Mission, which has spread throughout the world thanks to his first disciples. His most famous disciple was Narendranath Dutta, who became known to the West as Swami Vivekananda.

Vivekananda (1863–1902)

Vivekananda was born Narendranath Dutta. The Duttas were a well-known, philanthropic, educated Calcutta family. As a young man, Vivekananda was keen on serious matters. He read books on history and literature and marveled at divine creation. He was attracted to the intellectual approach of the new Brahmo Samaj philosophical movement, which urged its followers to reject rituals and image worship and worship the Eternal instead. The Brahmo Samaj was a group of intellectuals under the leadership of Raja Ram Mohan Roy, who took serious issue with the increased emphasis on rituals in Hinduism. The Samaj was alarmed that the true spirit of the Vedas was giving way to superstitions and mindless practices. They condemned child marriage and sati: the practice of persuading a childless widow to sacrifice herself on her husband’s funeral pyre. (This practice has been illegal for a couple of centuries now.) Brahmo Samaj became a force to be contended with in nineteenth-century Bengal.

Vivekananda never married and remained celibate to conserve his spiritual energy. But he did not follow the usual route to seeing God and seeking moksha (salvation). Distracted by the suffering of his countrymen, his personal salvation took a secondary role. He was focused on societal issues such as poverty, hunger, sickness, loss of confidence, and lack of self-respect that plagued Indians living under British rule.

Vivekananda believed that what India needed was to uplift its people, improve their living standards, and make their lives more bearable. He also believed that the way to accomplish these goals was through technology. So he journeyed to America to seek technology and assistance in order to improve the lives of Indians.

In the West, in exchange for the technology he needed to uplift India, he shared the dynamic message of the Vedas. He taught America the man-making message: “You are divine, not sinners! It is a sin to call you so. Get rid of your fears. Bliss is your birth right. Seek the One. Attain perfection. Learn the nonduality philosophy, Advaita, which insists Thou art That (tat tvam asi).” He encouraged Westerners to choose a path suitable to their personalities: Karma (selfless work in the service of humanity), Jnana (developing pure intellect to serve humanity), or Bhakti (total surrender in devotion). He also urged them not to identify themselves with their bodies and told them to be strong. He said, “I want muscles of iron and nerves of steel and a mind made of the same material of which the thunderbolt is made. Strength is life and weakness is death.”

In 1893, Vivekananda electrified the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, and religious leaders around the country took notice of the refreshing and bold approach to presenting the Hindu viewpoint. The Chicago Speakers Bureau set up a three-year tour of lectures and visits to Unitarians and other enthusiasts.

In 1897, Vivekananda established the Ramakrishna Mission, an Indian philanthropic organization that still flourishes today.

Shivananda (1887–1963)

The religious organization and ashram called the Divine Life Society owes its origin to a sage known as Swami Shivananda Saraswathi. He set the principal goals of aspirants as follows: serve, love, meditate, and realize. Each of these goals represents a yoga path: Karma, Bhakti, Raja, and Jnana, which I cover in Chapter 21. Swami Shivananda considered that birth as a human was precious and the goal of life ought to be realization of God and termination of the incessant cycle of births and re-births. To this end, he developed a series of steps an aspirant needs to take to keep fit, study, and serve.

Established in 1936 at Rishikesh in the Himalayas, the Divine Life Society now has 17 major centers around the world helping mankind lead a spiritual life. To understand the ideology and read about a variety of subjects focusing on leading a life full of meaning and joy, go to the Society’s website: www.dlshq.org.

Ramana Maharshi (1879–1950)

Born in a brahmin family, Ramana Maharshi fell in love with a pilgrimage center not far from his place of birth in Tamil Nadu. Somehow, the name Arunachala, a town dedicated to the worship of Shiva, created an ecstatic feeling in him, and while still in his teens, he decided to proceed there and settle down.

He stayed in a large cave-like opening under the Shiva temple, a location that suited his preference to be alone and to ponder the fundamental questions of life. While there, he became absorbed in deep meditation. His main thought was to understand “Who am I?” His conclusion was that a repeated inquiry of that fundamental question would reveal the truth — that is, that he (or any other aspirant) is the pure soul of the nature of Satchidananda (existence/conciousness/bliss). This became his emphasis and message to others who sought him.

He had little interest in developing a discipleship but, as it turned out, many people did gather around him. As a result, an ashram was constructed in his name at Thiruvannamalai.