4

Helping Yourself When You Reexperience a Trauma

Reexperiencing or intrusive reactions (those listed under the second criterion of the definition of PTSD given in chapter 1) are among the three major types of reactions in post-traumatic stress disorder (the other two are avoidance and physical symptoms). This chapter gives you ways to help you with intrusive symptoms. These techniques can be used when:

- memories or thoughts of the trauma suddenly pop into your mind

- you dream about the trauma over and over

- new aspects of the trauma come to you through nightmares or thoughts

- you feel as if the traumatic event is happening again

- you react to triggers such as a smell, sound, date, or any stimulus associated with your original traumatic experience that push you back into the trauma through a flashback (a momentary reliving of a past event in the present) or an abreaction (a full-blown reliving of the trauma in real time)

- you get really, really nervous or uncomfortable in a situation that reminds you of the trauma or is similar to the trauma

Building Dual Awareness

Before you work on trauma-related dreams, nightmares, memories, flashbacks, or other aspects of the trauma, it is very important for you to accept and reassure yourself that your trauma is not occurring in the present time. Having dual awareness helps you look at and work on the trauma while you are secure in the knowledge that you are really in the present environment. The following exercise gives you a tool to help you look at the trauma from the perspective of your observing self (now) and your experiencing self (then). You may do this exercise before you delve into your traumatic memories. It shows you the degree to which you have a capacity for dual awareness. This exercise was developed by Rothschild (2000, 130).

Exercise: Developing Dual Awareness

This exercise is from The Body Remembers by Babette Rothschild (2000, 131). Remember a recent mildly distressing event—something that made you feel slightly anxious or embarrassed. As you remember the event, what do you notice in your body? What happens in your muscles? What happens in your gut? How does your breathing change? Does your heart rate increase or decrease? Do you become warmer or colder? If there is a change in your body temperature, is it uniform (the same everywhere in your body) or does it vary?

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

Now bring your awareness back into the room where you are. Notice the color of the walls, the texture of the floor. What is the temperature of this room? What do you smell here? Does your breathing change as your focus of awareness changes?

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

Now try to keep this awareness of your present surroundings while you remember the slightly distressing event. Is it possible for you to maintain a physical awareness of where you are as you remember that event?

End this exercise by refocusing your awareness on your current surroundings.

*****

Matsakis (1998, 102–103) notes that hyperarousal (overexcitation) of the adrenal gland, which pumps out adrenaline, leads to the intrusive symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. She lists the consequences of this hyperarousal as:

- constant or frequent irritability leading to outbursts of anger

- sleep problems of all types, ranging from nightmares to difficulty going to sleep to difficulty staying asleep

- increased sensitivity to noise, pain, touch, temperature, or other stimuli

- increased heart rate or blood pressure

- agitated movement, tremors when at rest, gastric distress, incontinence

- hypervigilance (constant watchfulness because of feelings of vulnerability)

- immediate responsiveness to situations without taking time to think things through

- lack of self-control leading to self-shaming

- inability to assess situations accurately

- concentration difficulties

- focusing difficulties after exposure to a traumatic trigger (problems with seeing the whole picture rather than focusing only on one aspect of a situation)

- difficulties in problem solving because it is hard to maintain attention to nontraumatic aspects of the situation

- a higher baseline level of arousal (it is easier and quicker to become aroused)

- difficulties in calming down and soothing yourself

- feeling “crazy” when you can’t identify the trigger that led to your hyperarousal

- memory difficulties, particularly short-term memory difficulties

- increased use of substances

Dealing with Your Flashbacks

A flashback is a memory of the past that intrudes into the present and makes the past seem as if it is actually occurring in the here and now. Matsakis defines a flashback as a “sudden, vivid recollection of the traumatic event accompanied by a strong emotion” (1994a, 33). A flashback can occur as a slight “blip” in time or it can be a memory of an entire experience, occurring in real time just as it did in the past. This type of flashback is called an abreaction. Generally, the occurrence of a flashback cannot be predicted. Generally, flashbacks refer to visual and/or auditory parts of the trauma, but they can also refer to body memories (such as pain), emotions (intense anger that comes out of nowhere), and behaviors (acting in certain ways when a trigger comes up). Whenever a flashback happens, it feels as if the trauma is occurring all over again. You do not black out, dissociate, or lose consciousness during a flashback, but you do leave the present time temporarily. Rothschild says that memories “pounce into the present unbidden in the form of flashbacks” that can “reinforce terror and feelings of helplessness” (2000, 131). A flashback that occurs during sleep can be a nightmare or even a vivid dream. Meichenbaum (1994) notes that flashbacks also can appear as intrusive thoughts or reexperiences, or as intense feelings.

During a flashback, your traumas get replayed with great intensity; in many cases, unless you know how, you may not even be able to separate your flashback from present reality, reinforcing the impact of that trauma on you. Even young children can have flashbacks; however, they tend to act them out rather than express them in words. Sometimes children may act out upon others what was done to them; e.g., a nine-year-old boy who sexually acts out toward a younger sibling may be having a flashback, rather than just acting as an offender.

Ruth, thirty, suddenly feels her uncle’s body on her as she is taking a shower, and recognizes his touch. The uncle molested her twenty-five years before. Margaret, thirty-five, lives in an apartment with two other persons. Their upstairs neighbors play music until late at night. When Margaret and her roommates complain to the management, the male renters upstairs retaliate by banging on the ceiling at all hours of the night and by scratching up Margaret’s car and the cars of her roommates. Margaret is a date rape survivor, and these neighbors’ behavior has led to flashbacks of her own attacks twenty years before. She is hypervigilant as she prepares for a potential attack.

Sometimes it is very difficult to make sense of flashbacks, particularly when there are not explicit events to use as reference points for them. Flashbacks may involve explicit memories of entire scenes of traumatic events or just parts of the events. Usually a flashback also includes some emotional and sensory aspect of the traumatic event. This means that your entire nervous system is involved when you have a flashback; your nervous system becomes hyperaroused when you are exposed to trauma triggers.

Sometimes, flashbacks occur as part of a memory that you thought had been worked through. When this happens, you might ask yourself the following questions:

- What is the flashback trying to tell me?

- Do I have more to see?

- Do I have more to feel?

- Do I have more to hear?

- Do I have more to learn or accept about what happened to me?

- Am I able to grab onto only this piece of the memory without getting lost?

Through some of the techniques in this workbook, you can learn to deal with flashbacks in different ways.

Exercise: Beginning to Deal with a Flashback

Think of a flashback you have had in the past two weeks.

Describe the flashback and what you experienced.

___________________________________________

Have you had a similar flashback in the past? If so, when and under what conditions?

___________________________________________

How did the flashback smell, feel, or sound? Who was involved?

___________________________________________

How did the actual traumatic experience smell, feel, or sound? Who was involved?

___________________________________________

How are the flashback and the past traumatic situation different or the same?

___________________________________________

What actions can you take to feel better as the flashback occurs?

___________________________________________

How can you ground yourself to stay in the present when flashbacks occur?

___________________________________________

How did you feel as you did this exercise? You can use it for any flashback you have.

___________________________________________

*****

The VCR Technique

Another way to deal with flashbacks is to put the memories that repeat in a shortened form on a “VCR tape” in your mind. Then you can play the memory in small sections using the on and off controls. You can even fast-forward or rewind. These actions give you a sense of choice and control about remembering. You can also add something else to the beginning or end of the memory, to frame it—perhaps an alternative solution to what happened, or an image of your safe place.

Exercise: Using the VCR Technique

- Before you work on a traumatic flashback with this technique, try it with a positive memory of an event that you’ve experienced.

The event that I am going to use is:

___________________________________________

When I fast-forward through this event, I (saw, felt, heard, smelled, experienced, etc.)

___________________________________________

When I rewind this event, I

___________________________________________

When I frame this event with other pictures, I

___________________________________________

If I were to use positive images to frame my flashback, I would use these:

___________________________________________

- If you don’t feel immediately comfortable with this technique, practice it more, until you are comfortable. Then try it with a traumatic flashback.

The flashback that I am going to use is:

___________________________________________

When I fast-forward this event, I

___________________________________________

When I rewind this event, I

___________________________________________

When I frame the event with other pictures, I

___________________________________________

How comfortable was this technique to use with a flashback? Was it more or less comfortable than when you used it with a positive memory?

___________________________________________

*****

Getting Outside Your Head

One important way to deal with a flashback is to get it outside of your head into the world around you. You can do that by writing about it, talking about it, drawing it, collaging it, or otherwise representing it someplace other than in your mind.

The next few pages will give you guidance about dealing with your flashbacks. If you are currently in therapy and find doing these activities to be too powerful, wait until you are in a therapy session to complete them. If you have a supportive person who is willing to listen to you talk about your flashbacks, then work on this section of the book in close contact with that person. Working on flashbacks can be very powerful and it is important that you take care of yourself while doing so.

Journal Exercise: Defusing Flashbacks

Dolan has developed a four-step approach to help defuse flashbacks (1991, 107). To use it, answer the following questions in your journal:

- In what situation(s) have you felt the same way before?

- How are the current situation and the past situation similar? Is there a similar setting, time of year, sound, or other aspect? If there is a person involved, how is that person similar to one who was involved in your trauma(s) in the past?

- How is the current situation different from the past situation? What is different about your current life circumstances, support systems, or environment? How are the persons around you different from those involved in your traumatic experiences?

- What actions can you take (if any) to feel better now, particularly if you feel unsafe in your flashback? If your flashback is merely an old memory that does not cause you to be unsafe, you may merely need to give yourself a positive message that you can survive or work through it or do something different. However, if you truly are unsafe, it is important to be aware of the real danger and protect yourself.

*****

The Rewind Technique

David Muss, a British psychiatrist, has developed the following technique to allow you to get rid of your unwanted, involuntary memories of the traumatic event and the emotional distress that they bring (1991). When you try this technique, do so in a safe setting; you may wish to work on it first with a therapist.

- Find a time when you can be safe and undisturbed.

- Find a comfortable place and sit there quietly for fifteen minutes before beginning the rewind.

- Begin to relax, using the techniques you learned in chapter 2. Keep your eyes closed, and tense and relax each muscle group of your body, beginning with your feet.

- Feel the calmness that comes over you as you relax. You might also think of a pleasant place or your safe place while you do this relaxing.

- Now allow yourself to float out of yourself so you can watch yourself sitting in your comfortable place. Choose a memory in which you felt somewhat sick or frightened, e.g., just before going down the largest drop on a roller coaster. Thinking of this memory will make you feel somewhat uncomfortable. Now look at that same scene from outside the roller coaster. Float above yourself and watch yourself. Hopefully, you do not feel as bad now.

- Now you need to experience two films. Imagine that you are sitting in the center of a totally empty movie theater with the screen in front of you and the projection room behind you. Now float out of your body and go to the projection room. See yourself sitting in the theater, watching the film. From the projection room, you can see the whole theater as well as yourself.

- Watch the first film. The first film replays the traumatic event as you experienced it or as you remember it in your dreams, flashbacks, or nightmares. You will see yourself on the screen. It is as if someone took a video of you during the trauma and that video is now playing. When you start the film, begin it at the point just prior to the traumatic event, seeing yourself as you were before it occurred. Remember, you are sitting in the movie theater to watch the film, but you are also in the projection room watching yourself in the theater as you watch the film. Play the film at its normal speed. Stop the film when you realized you were going to survive or when your memory begins to fade.

- The second film is the rewind. You will not watch the rewind, but you will experience it on the screen, seeing it as if it were happening to you now, with all of its sounds, smells, feels, tastes, and touch sensations. You are actually in the film, reexperiencing the event. However, you see and experience it all happening backwards, from after the traumatic event until before the event happened. This reexperiencing takes practice and must be done rapidly. Remembering a trauma of about one minute would mean having a rewind of about ten to fifteen seconds.

You may find rewinding hard to do initially. However, keep practicing until it feels right. You may find it painful to go through the first film. After you learn this process, every time you begin to remember the trauma, you can use the rewind to scramble the sequence of events and to take you quickly back to the starting point—the good image. You will be left with the prevent memory after the rewind. As time goes by, your rewind process will happen faster and faster. It is very important to include all the frightening, awful details of the trauma in your movie. Also, as one memory gets resolved by rewind, others may appear to take its place, memories that have been hidden under the surface of the first. These too can be addressed through this process.

If you try the rewind process, use this space to describe how it worked for you.

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

Other Ways to Deal with Flashbacks

You may use any of the following techniques to help you put a flashback out of your awareness and return to the present. Some of them are designed to be quick, while others take time. Do not worry if many or most of them do not work for you. Try them out and choose those that work best.

- repeatedly blink your eyes hard

- change the position of your body

- use deep breathing (from chapter 2)

- use imagery to go to your safe place in your mind

- go to your actual safe place

- move vigorously around your environment

- name objects in your environment out loud

- hold onto a safe object

- listen to a soothing tape, e.g., one a therapist made for you if you are in counseling

- clap your hands

- stamp your feet on the floor

- wash your face with cold water

- say positive statements (affirmations) about yourself

- spray the memory with a bottle of (imaginary) cleanser until it goes away

- project the flashback onto a dry erase board and then erase it; do the back and forth movements of the eraser with your hand

- draw the flashback on paper, then do something with the paper (shred it, burn it, bury it)

- put the flashback into some type of vault or container (real, on paper, or symbolically, in your mind)

Containment and Traumatic Memories

Containment means using your mind to focus attention on something other than a traumatic memory, flashback, or thought. It is possible to contain those reminders of the trauma and remain in the present, in spite of having strong feelings. Learning containment techniques can help you tolerate those feelings without taking negative action against yourself or others. Containment is based on choice rather than automatic response; it helps you store overwhelming, unsafe memories until you are ready to process them. However, containment does not involve indefinite avoidance or denial. In fact, learning how to contain memories means that using numbing and dissociation to deal with trauma is less necessary.

The following containment techniques were developed by a Dissociative Identity Disorders support group at Dominion Hospital in Falls Church, Virginia. The group noted these ways to contain traumatic intrusions (flashbacks, memory fragments, thoughts):

- Plan ahead for potentially distressing times when you have some advance warning of them.

- Allow yourself to cry to get out emotion.

- Record your thoughts and feelings on paper or tape.

- Perform a monotonous activity to distract yourself: play solitaire, do a puzzle.

- Ground yourself in the present time by reminding yourself that you are in the here and now (use dual awareness). Grounding might include grasping a favorite object and focusing attention on that contact as a way to stay in touch with reality; using your body’s contact with the furniture or floor to remind you of your present location—stomp your feet or push your body into a chair; or using your body’s own physical properties by clapping your hands, or touching your tongue to the roof of your mouth.

- Put the memories into a real or imagined container outside yourself, and then close the box until a more appropriate time.

- Count to yourself; use your watch or pulse as ways to count.

- Get involved in an activity that involves some type of motion (such as walking or exercising).

- Use art materials to express your emotions or represent the memory.

- Go to a potentially traumatizing event with your camera, and take photographs as a way to hide behind the camera and avoid some triggers.

Using Dual Awareness to Treat Flashbacks

The following flashback-halting protocol, from The Body Remembers by Babette Rothschild (2000, 133), is based on the principles of dual awareness we mentioned earlier in this chapter. It is designed to reconcile the experiencing self with the observing self and generally will stop a traumatic flashback quickly, according to Rothschild (2000, 132). Practice this technique on “old” flashbacks (those you have had, processed, and perhaps put to rest) so that you can learn it well. And then use it later when you have a flashback that includes new memories or previously unknown traumatic events or material.

Exercise: Flashback Halting Protocol

The flashback I am using is ____________________________

___________________________________________

Say to yourself (preferably aloud) the following sentences, filling in the blanks:

Right now I am feeling _________________________ (fill in the name of your current emotion, usually fear) and I am sensing in my body ______________________________ (describe your current bodily sensations—name at least three), because I am remembering _________________________ (identify the trauma by name only without details) ______________________________________.

At the same time, I am looking around where I am now in _________________________, (the current year), here _________________________ (name the place where you are). I can see _________________________ (describe some of the things that you see right now, in this place), and so I know _________________________ (identify the trauma again by name only) is not happening anymore.

How did this technique work for you? What was it like to do it?

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

*****

Changing Negative Thoughts to Positive

An additional technique you can use when you have a flashback is to change the negative thoughts that occur after the flashback (e.g., I’m a failure for having this flashback; I really couldn’t protect myself) into more positive thoughts. This is done through self-dialogue. Say to yourself, if you are afraid after a flashback, “This is now, not then; I did everything I could do (to protect myself) during the (traumatic event). I survived then and I will survive now.”

Exercise: My Preferred Flashback Technique

What have you learned about your flashbacks and how to control or deal with them through doing these exercises?

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

Which exercise(s) helped you most?

___________________________________________

*****

Nightmares and Dreams of the Trauma

You may have recurrent dreams that have some aspects of the trauma. Perhaps these dreams do not scare you, or they may be nightmares that wake you and leave you feeling fearful and panicked. Sometimes dreams about traumatic events can actually give you information about what happened to you.

A woman once had dreams about a face without a body. This face appeared in her dream on many, many occasions. The face was very dark complexioned and had a mustache and scars of pimples on the cheeks. She had no idea if the face actually belonged to a person; she knew no one that fit its shape and appearance. After years of therapy, the woman was ready to confront her older brother about the sexual abuse he perpetrated on her. She sat him down and spoke firmly what she had practiced over and over in the therapist’s office—how he had harmed her and disrupted her life. The brother began to cry. He said that he had hoped she had not remembered what he had done to her when she was under eight years of age. He begged her forgiveness and then said that he needed to “come clean and tell her about the rest of the stuff.” The woman was baffled by his comment. “What do you mean?” she asked her brother. He began to tell her of taking her into an attic above a deserted store with a group of his friends. One of his friends, a dark complexioned teen with a mustache and scars from acne, raped her. Her memory of the rape only occurred in her dreams, only in the face of the rapist.

The flashback-healing protocol based on dual awareness (see “Exercise: Practicing Dual Awareness” above) can be adapted to use with nightmares that may be traumatic flashbacks. You may use it as a ritual before sleep to prepare for any nightmares that may occur, or you may keep it beside your bed to use when you need it.

Exercise: Dealing with Nightmares

This exercise is from The Body Remembers by Babette Rothschild (2000, 134). Say these things to yourself, preferably aloud, before you go to bed. Or, if you awake with a nightmare, be sure to try to ground yourself before you do any work on what you dreamed (see technique 5 in the section “Containment and Traumatic Memories” above for quick grounding ideas).

I am going to awaken in the night feeling _________________________, (insert the name of the anticipated emotion, usually fear) and I will be sensing in my body, _________________________, _________________________, _________________________ (describe your anticipated bodily sensations; name at least three) because I will be remembering _________________________ (identify the trauma by name only—no details). At the same time, I will look around where I am now in _________________________ (the current year), here _________________________, (name the place where you will be). I will see _________________________ (describe some of the things that you see right now, in this place), and so I will know _________________________ (identify the trauma again by name only) is not happening anymore.

*****

Baker and Salston (1993) discuss ways to deal with dreams through dream preparation. In dream preparation, you follow a cognitive (thinking) procedure before you go to sleep, recognizing that you may dream a distressing dream during sleep. When the dream occurs, you write it down, talk it through, and rewrite its ending, as a means to take control of the dream. Then you do relaxation exercises and go back to sleep. Baker and Salston also suggest that you might write out your nightmares in detail and then rewrite the ending as a way to take additional power and control. The following exercise is adapted from Baker.

Exercise: Nightmare Form 1

Describe your trauma-related nightmare in the space below (if you need more space, use your journal). Describe it in as much detail as possible, including the scene, any associated feelings, and as many sensory items as you can possibly remember (smells, sensations on your skin, sounds, sights, tastes). If you have more than one nightmare about the trauma, photocopy this page and use a different sheet for each (adapted from Baker, in Baker and Salston 1993).

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

Is your nightmare an exact reenactment of the traumatic event? Yes / No (circle the appropriate answer)

Now think of ways to change the nightmare’s ending:

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

What new information does the nightmare give you that you can use to build an understanding of what happened to you?

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

How has the nightmare helped you or helped you to respond differently to your trauma?

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

*****

Triggers: Reminders of Trauma across the Senses

A trigger is a piece of an event that intrudes into the present and reminds you of what happened in your past. When you react to a trigger of a traumatic event, your adrenal glands get aroused and memories of the traumatic event get activated, as do emotions associated with the event. These reactions may occur even when you do not recall the exact traumatic event—the physiological reactions can get resurrected by themselves (Matsakis 1994a). Triggers may exist for nontraumatic events, as well; for example, smelling brownies cooking may trigger pleasant memories of childhood. However, traumatic triggers are often unpleasant or frightening. They may lead to a flashback or to feelings of anxiety, panic, fear, anger, rage, confusion, shakiness, or numbness, or to a sense of spacing out or dissociation. They can retraumatize you.

It can be helpful to develop a list of triggers that lead to flashbacks or to the unpleasant feelings associated with trauma. Once you have identified your triggers and are aware of them, you will be more able to bring them under control, and even choose not to react to them. In your journal, you may write about, draw, collage, or otherwise represent triggers of your traumatic event(s). In the next few pages you will also be asked to write down your reactions to those triggers when you experience them. It is important to keep some type of record of when the flashback occurred after exposure to the trigger, and of where you were, what you were doing, who was with you, and what exactly happened. Once you have identified your triggers (or at least have begun to keep a trigger list), you can then learn how to avoid or defuse them in less time. It is also important that you identify ways that you got past the triggered flashbacks or feelings if they occurred previously. Identifying any small sign of returning to the present can help you control triggered reactions.

Journal Exercise: My Trigger List

This exercise has three parts: the list, your past reaction to your triggers, and you ideas for future responses.

- In your notebook or journal, write about or list your triggers using the following topics.

triggers associated with what I saw

triggers associated with what I heard

triggers associated with what I smelled

triggers associated with what I touched or with what touched me

triggers associated with what I tasted

triggers associated with certain places

triggers associated with certain persons. (If a person is a trigger, try to determine what specific behavior, characteristics, or attitudes of the person trigger you. Then look at the specific aspects of the trauma that are triggered by this person, and at how the person relates to the traumatic event(s). Triggers might relate to the age of a particular person, e.g., the person may now be at the age with which you associate the traumatic event.

triggers associated with nature or time (e.g., weather, seasons, time of day)

- In the next eight pages of your journal, write down your various reactions to triggers you have experienced. How do your more recent reactions compare to the reactions you have had in the past? What good things happened in those reactions? Did you experience any positive emotions or have any pleasant memories? What bad things happened? How likely do you believe it is that you will experience the trigger again? Use the following format, writing one topic at the top of each page: The positive and negative ways I have reacted to triggers associated with what I saw [heard, smelled, touched, tasted during] in the [the places, persons, or aspects of nature or time associated with] traumatic events are:

- Now think of ways you might deal with each of these triggers in the future to take power away from them. Write a response for each of the eight trigger areas on a separate page in your journal or notebook.

*****

Managing Trigger Events

When you learn to take more control over your triggers, the trauma loses some of its power and control over you. In controlling your triggers, it is important to plan ahead and find ways to deal with them before they occur. It is also important to identify persons who might help you deal with the triggers. Power (1992a) lists ways to manage triggers that may help you plan your own strategies and techniques. They include:

- relaxation exercises

- breathing exercises

- appropriate medication

- contact with supportive others

- establishing manageable lists of priorities

- avoiding extra stress

- structuring your life to avoid contact with certain specific triggers

As Matsakis noted, “the goal is to manage the trigger event, not…have no negative feelings or sensations about it” (1994b, 147). As you plan ways to deal with the specific triggers you named, it might be best to start by working on triggers that you believe are easiest to manage or control. Some triggers, such as seeing your perpetrator face-to-face, may take months or years to learn to overcome, if you are ever able to manage them. As you plan your strategies, think of your history with each particular trigger, the symptoms that the trigger evokes, the specific fears associated with the trigger, and the coping mechanisms you will use.

Remember, it is your choice how you deal with each and every trigger you have listed in your journal. You can never avoid everything that triggers you. Thus, as Meichenbaum notes, it is important to control your own inner experience rather than try to avoid everything that triggers your automatic responses (1994). You can disarm a trigger when you understand how the past is not the present.

Trigger work can be very stressful. It always involves some type of processing of the feelings associated with the trauma so you can know they can no longer hurt you. You may always turn to some of the self-soothing exercises in chapter 2 should you begin to feel overwhelmed. You may also use these calming exercises when you are aware that a trigger is about to happen. The following exercise is designed to help you with a specific trigger that you have chosen from the previous pages. If you want to deal with more than one trigger, photocopy this exercise and use one copy for each trigger. If some triggers are too difficult to face alone, do not do this exercise, or do it only in the presence of your therapist or in a group situation designed to work on trauma. Please remember, too, that you cannot get rid of the power of a trigger over night. It takes time to substitute new behaviors for old ones.

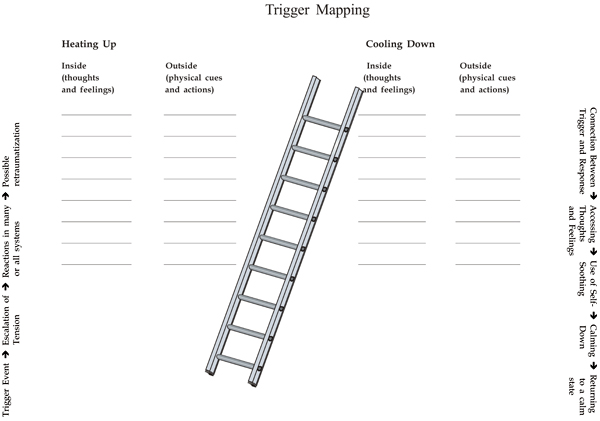

The Trigger Mapping Ladder

There are many ways to represent triggers. One of these, the trigger mapping ladder, was developed by one of the authors of this book as she worked with a group of persons diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder (formerly called multiple personality disorder). The ladder is a diagram showing that trigger events lead to an escalation of tension, which causes many different systems in a person to react and may lead to retraumatization. Thoughts and feelings, physical cues and actions can either heat up or cool down triggers. Cooling down the trigger response involves taking away its power. It helps you make the connection between your triggers and your responses, look at your thoughts and feelings, calm yourself, and find meaning in the entire process.

This process can help you bring control into your life by separating the past from the present and changing the way you react to your trigger(s). Approach each rung of the ladder slowly and calmly, and take small steps up and down it. Some images and symbols of your triggers can lead you to more information about your traumatic experiences, serving as clues to what happened to you and why you react as you do.

Exercise: Dealing with My Trigger

If you want to deal with more than one trigger, photocopy this exercise and use one copy for each trigger.

- When you distract yourself from the power and influence of the trigger, that trigger eventually will have little or no power over your life in the present. I choose to distract myself from __________________________________(name the trigger) by __________________________________

___________________________________________

Some other ways I may distract myself (examples might include listening to, singing, or whistling you favorite song as soon as the trigger starts; covering your ears or using earplugs; talking to yourself about what is real or not real, or about the present):

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

- I choose to practice staying present in the now when I experience this trigger by grounding or using other techniques I have learned.

For example, I may ignore __________________________________(name the trigger).

I may also ____________________________________________________.

Or, I may name five, then four, then three, then two, then one thing(s) I see, hear, or smell around me:

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

- Now, after you have tried one or more of these ways to gain control of a trigger, write about that experience and how it felt:

I was> __________________________________(name the trigger) occurred.

When I began to have a reaction to __________________________________(name the trigger), I chose to (distract myself, ignore it, stay present) by ___________________________________________________.

When ____________________________________________(name the trigger) began to fade in its power, I felt __________________________________ and then I (describe what you did)

___________________________________________

*****

The Trigger Mapping Ladder

Going up the left side of the ladder are four phrases. Starting at the bottom, next to where it says “Trigger Event,” write in the name of an internal or external trigger—a sight, sound, smell, time of year, thought, or other event or thing. Above the event or thing, write in what types of reactions you have as you become aware of your reaction to the trigger. What in your body gets tense? What emotions surface? Moving up one step to the space marked “Escalation of tension,” write in how you react. You may not have a response for each one of these sections, but write in as many as you can. Once the trigger has led to your reaction, what is that reaction? Do you have a full-blown flashback? Do you feel uneasy? Do you break into a cold sweat or begin to cry? Do you feel as if you are retraumatized?

On the right side of the ladder, going from top to bottom, are a series of phrases describing behaviors that may help you deescalate the trigger. What might you do for each of them? What thoughts and feelings might help you to take away the trigger’s power? One might be “I am in the present; the trigger is from my past and it is not happening now.” Another response might be “I need to take five deep cleansing breaths.” Again, you may not have a response to each phrase but put in whatever you can that might help you lessen the trigger’s hold on you.

Here’s an example of how the ladder might work for a particular situation. Let’s say you are a survivor of sexual abuse. You have to go to family function, your father’s birthday party, and know that your grandfather, who abused you, will be present. As you think about the party, you notice that you begin to have escalating tension both in your body and in your thoughts and feelings. How is your body reacting—where does the tension begin? At first, your shoulders get tight and your palms begin to sweat. Then you get a pounding headache and you begin to remember a specific abusive encounter that leads to pain in your lower abdomen. At the same time, you have thoughts of wanting to escape, wanting to avoid going to the party. You feel frightened and may even begin to experience a panic attack. You may even hear some of your grandfather’s words in your mind and your thoughts about him swim quickly.

What can you do? How can you combat all these feelings and physical symptoms? On the right side of the ladder are spaces for you to de-escalate. You may say to yourself, “This is now, that was then; I am an adult now and can protect myself; he is a little old man.” You may also recognize that the physical cues you are having reflect back to the early abuse. As you process what is going on, you might begin to look at what you can do to combat both the physical reactions and the feelings. You might set up a strategy to keep out of direct contact with him. You may ask your husband/partner to run interference. You may decide to approach him and warn him to leave you alone. You may even think of ways to avoid the party. Then you can begin to self-soothe. You may take deep breaths, go for a walk, listen to music, or write out a script to say to your abuser. As you calm, think of things that can bring you back to the here and now. When you feel calmer, look at the process and how you have helped yourself. Realize that this process is difficult and may take time (and practice) to work. Trying to do the process is the first step to overcoming major reactions to triggers!

Using Activities and Anchors to Reduce Triggers

Another way to gain some control over your traumatic triggers, dreams, nightmares, and intrusive thoughts is to participate in activities that can give you a break from reexperiencing your trauma. Helpful activities, according to Rothschild (2000), are those that need your concentration and attention so that the intrusions of trauma don’t take over. It is easy for intrusive thoughts to wander in while you’re watching a movie on the VCR. However, they do not come in as easily if you are doing something that demands attention and body awareness. For example, you may iron clothes, keeping enough awareness of what you are doing that you don’t burn them or yourself.

Another way to help yourself is to use an anchor. Rothschild describes an anchor as “a concrete, observable resource,” or one that is outside your own mind (2000, 91). That resource may be a beloved person or pet, a place (e.g., your home), an object, or an activity. The resource helps you feel relief and well-being in your body; thinking about it can serve as a braking tool for a trigger or intrusive thought without changing reality. Your safe place, which you described previously, is another anchor that can provide protection for you.

What are some activities you could use to control your intrusive thought?

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

What are your own personal anchors?

___________________________________________

Exposing Yourself Safely to Your Past Traumas

You may have noticed that we have not asked you to describe your traumatic memories in great detail. Such exposure is more of a task for therapy. We do not want to retraumatize you by overwhelming you with memories. The closest we have come to directly exposing you to the trauma has been asking you to write about what happened to you. Putting your traumatic experiences into a story with a beginning, middle, and end helps diffuse the strong emotions associated with the traumas (Meichenbaum 1994).

Direct exposure therapy, where you look at your traumatic memories in detail, needs to be done under the guidance of a professional in a course of anywhere from nine to fourteen sessions of sixty to ninety minutes each. Direct exposure therapy takes you back into your traumatic experience and asks you to tell:

- when the traumatic event happened

- how long it lasted

- the entire story, from the start of the incident to after it was over

- everything of which you are aware about the setting and the event

- about any earlier incident(s) similar to the one you are describing

- your interpretation of the impact the event has on you at the present moment

All of the description is done in the present tense and in great detail. Direct exposure therapy needs a great deal of preparation in order for you, as the client, to endure the process without experiencing overwhelming anxiety, suicidal thoughts, or intense fear. The motto behind doing this work is “no pain, no gain.” However, the extent of pain that can be caused by exposure therapy or overexposure to the traumatic event is too great to include it as part of the work in this workbook. This description of exposure therapy is included here merely as information about another way to process what has happened to you.

The Flower Diagram

If you want to take a part of a memory or an entire memory and look at it in more detail, you might use the flower diagram below as your guide. When analyzing any memory using the flower diagram, you have six separate sections to examine: sensory information; beliefs; body reactions; emotions; wants; and actions. Try not to allow yourself to reexperience it as you write in your answers; try to imagine you are looking at it on a TV or movie screen.

Exercise: My Flower Diagram

At the center of the diagram, write in the memory that you wish to examine. In the first petal of the flower, write in any sensory experiences that come to mind when you think about the memory. What smells, sights, sounds, or touch sensations come to mind? In the next petal, write in your thoughts and beliefs about the trauma. What messages were told to you before, during, and after that trauma that you have incorporated into your own mind (your introjects)? What conclusions have you reached about the trauma (for example, I believe it was my fault; I believe I can never be safe; I believe that I caused the event to happen; I believe that I was not to blame for anything that happened)? In the next petal, record how your body reacted during the traumatic event. Did you freeze, run away, cry, or numb yourself, for example? In the fourth petal, write down any emotions that you can remember having. Were you terrified? Embarrassed? Shocked? In the fifth petal, write down any “wants” you had during the trauma. Did you want to dissociate? Did you want to just go away, or did you want to attack the perpetrator? Finally, in the last petal, record any actions you took. Did you choose to escape through dissociation? Did you fight back? Did you participate in some way? If you do not have total recall or even partial recall of any of the sections, you may have some degree of what is called traumatic amnesia, or forgetting. Just write in what you do remember. If you need more space, you may use additional pages in your notebook to record the information. Remember, try to keep a distance from the memory and the traumatic event as you complete this exercise.

Exercise: What I Learned from This Chapter

In this chapter, you have learned some ways to deal with the intrusive, reexperiencing aspects of PTSD. These are only some of the many different techniques available. Hopefully, through practice and effort, they will work (at least to some degree) for you. Remember, you can refer back to the exercises in this chapter whenever you need to do so.

What have you learned about yourself through the work you have done in this chapter?

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

How did the techniques provided in chapter 2 help you calm yourself if you needed to do so?

___________________________________________

___________________________________________

*****

The diagram is adapted from Miller, Wackman, Nunnally, and Miller (1989).

Avoiding Avoidance

There are other ways to cope with traumatic events. One way is to try to avoid or deny what happened to you. Some denial is natural but, at times, avoiding the impact on you of your traumatic events can be detrimental to you. The next chapter looks at some ways you can lessen your avoidance.