At the start of the summer Timoshenko and Zhukov had consistently warned Stalin that their intelligence showed war was imminent and urged for full mobilisation. Stalin steadfastly refused to believe Hitler would attack and even dismissed intelligence from a spy within Luftwaffe headquarters, who had confirmed the impending assault.

The Soviet leader continued to dither. Following the military commanders’ briefings at the Defence Ministry on 13 June, Timoshenko sought Stalin’s permission to bring the border districts to war readiness. Frustratingly, Stalin did not agree to the deployment of the second echelon divisions in the border areas until four days later.

Nikita Khrushchev, who should have been in Kiev monitoring the Ukrainian border, found himself summoned to the Kremlin. He was very concerned by Stalin’s complete air of defeatism:

He’d obviously lost all confidence in the ability of our army to put up a fight. It was as though he’d thrown up his hands in despair and given up after Hitler crushed the French army and occupied Paris. […] I was with Stalin when he heard about the capitulation of France. He’d let fly with some choice Russian curses and said now Hitler was sure to beat our brains in.1

During a Politburo meeting on 18 June, Stalin was extremely dismissive and belittling of his two most senior generals, accusing them of warmongering. ‘So you see,’ said Stalin:

Timoshenko’s a fine man with a big head but apparently a small brain. I said it for the people, we have to raise their alertness, while you have to realise that Germany will never fight Russia on her own. You must understand this.2

He stomped out of the meeting room only to poke his head back in to warn, ‘If you’re going to provoke the Germans on the frontier by moving troops there without permission, then heads will roll, mark my words’, and with that he slammed the door.

Timoshenko and Zhukov privately despaired of their leader’s seeming indifference to the threat gathering on their borders. They gained absolutely no support from the Politburo members, who did not wish to displease their leader. Khrushchev tired of kicking his heels and two days later insisted he be allowed to leave for Ukraine:

Finally I asked him outright, ‘Comrade Stalin, war could break out any hour now, and it would be very bad if I were caught here in Moscow or in transit when it starts. I’d better leave right away …’

‘Yes, I guess that’s true. You’d better leave.’

His answer confirmed what I’d suspected: that he hadn’t the slightest idea why he’d been detaining me in Moscow. He knew my proper place was in Kiev. He had kept me around simply because he needed to have company, especially when he was afraid. He couldn’t stand being alone.3

To the very last, the Politburo said exactly what Stalin wanted to hear. On the very eve of Hitler’s attack Interior Minister Beria took the opportunity to ingratiate himself with his boss. On 21 June, he denounced Golikov as a liar after his latest warnings and sent Stalin a note declaring, ‘My people and I, Iosif Vissarionovich, firmly remember your wise prediction: Hitler will not attack us in 1941’.4

Even so, Pavlov’s Western Military District received a message from Timoshenko and Zhukov at 0045 hrs on 22 June. It read:

A surprise attack by the Germans on the fronts of Leningrad, Baltic, Western Special, Kiev Special and Odessa Military Districts is possible during the course of 22–23 June 1941.

The mission of our forces is to avoid proactive actions of any kind … At the same time, the … Districts’ forces are to be at full combat readiness to meet a surprise blow by the Germans or their allies.5

This seemingly contradictory warning was simply too late. The Red Air Force had not been permitted to intercept Luftwaffe incursions over eastern Poland, where its aircraft were lined up on the runways with parade precision ready to be bombed. Many of the Soviet Army’s divisions were simply too poorly equipped to fend off Hitler’s onslaught. Critically, there was a shortage of weapons and ammunition. The rifle divisions also lacked transport, spares and fuel. The bulk of their communications relied on landlines rather than radio, and this greatly hampered the armoured units.

The ongoing mobilisation was a mess. Anastas Mikoyan, minister for food supplies, acknowledged there were not enough rifles to go around:

We thought we surely had enough for the whole army. But it turned out that a proportion of our divisions had been assembled according to peacetime norms. Divisions that been equipped with adequate numbers of rifles for wartime conditions held on to them, but they were all close to the front. When the Germans crossed the frontier and began to advance, these weapons ended up in the territory they controlled or else the Germans simply captured them. As a result, reservists going to the front ended up with no rifles at all.6

General Voronov admitted:

Many of our units in border districts did not even have rifle cartridges before the beginning of the war, to say nothing of live artillery shells. With the knowledge of the General Staff, prime movers [gun tractors] were withdrawn from artillery units and used in the construction of fortified regions along the new western border. As a result, the guns were immobilised and could not have been used in the fighting.7

Timoshenko had cleverly advised the district military commanders to hold exercises in the direction of the frontier as a surreptitious way of moving their troops forward. This was done, but the artillery was left behind. This was either because they could not be moved or had been sent to the firing ranges for training.

Hitler’s titanic assault on Stalin was heralded at 0315 hrs on Sunday, 22 June 1941, when the Luftwaffe hit the Red Air Force’s frontier airfields. In the Kremlin, Stalin and his cronies, upon hearing this news, were panic-stricken. Despite clear and compelling evidence to the contrary, Stalin had continually insisted Hitler would not attack; he had now been proved badly wrong.

The Soviet leader’s initial response to Hitler’s invasion was one of self-denial. He knew he had stayed the hand of the Red Army at the critical moment and was now paying the price. For a brief moment, it appeared as if Stalin might buckle under the enormous strain. There have been claims that he had some sort of nervous breakdown, but there is little evidence to support this. Zhukov called Stalin at Kuntsevo, his dacha retreat outside Moscow, for permission to counter-attack. Just thirty minutes after Hitler’s offensive commenced, Stalin summoned the senior leadership of the Politburo, including Timoshenko and Zhukov, to the Kremlin to discuss the situation.

A bemused General Kazakov had flown in to Tashkent on the night of 21/22 June. He spent several hours briefing his superior then went off to get some much-needed sleep. He was awoken on the instructions of the duty officer – an urgent call had just come through from the General Staff in Moscow. The message simply stated, ‘It has started’. He strode off to find his boss, Trofimenko. Kazakov must have cursed his luck that he was now thousands of miles away from the action. He was determined to secure a combat command.

In the meantime, the poor leadership of the Red Army showed through immediately. Georgy Semenyak, serving with the Soviet 204th Rifle Division, was numbed by the ferocity of Hitler’s blitzkrieg and aghast at the performance of his officers, ‘The lieutenants, captains, second lieutenants took rides on passing vehicles … mostly trucks travelling eastwards. […] The fact they used their rank to save their own lives, we felt this to be wrong.’8

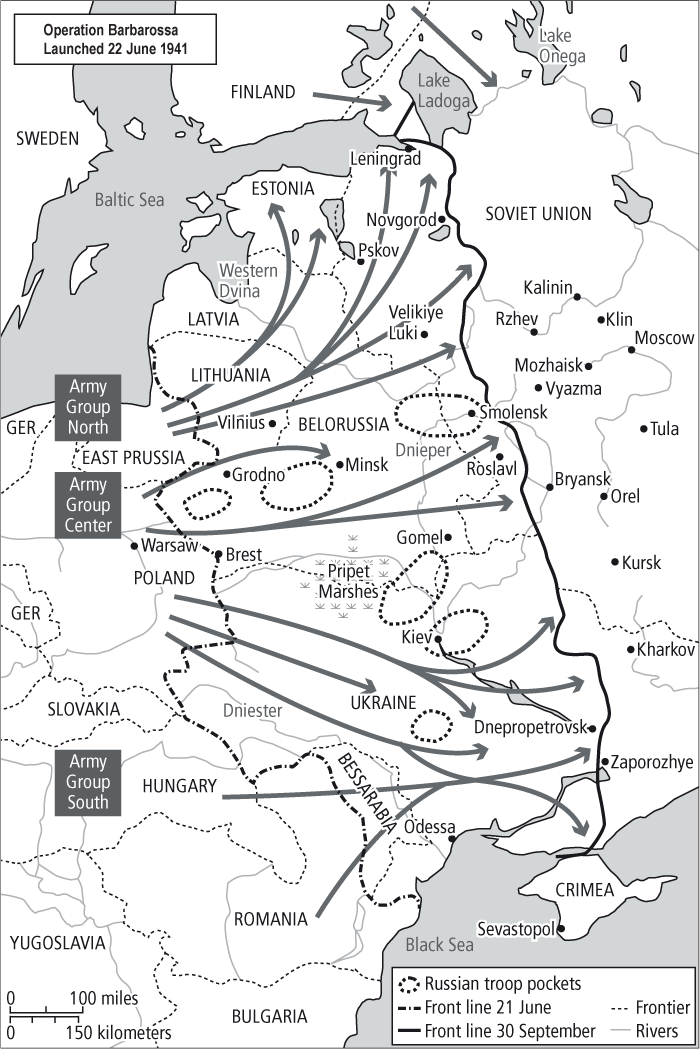

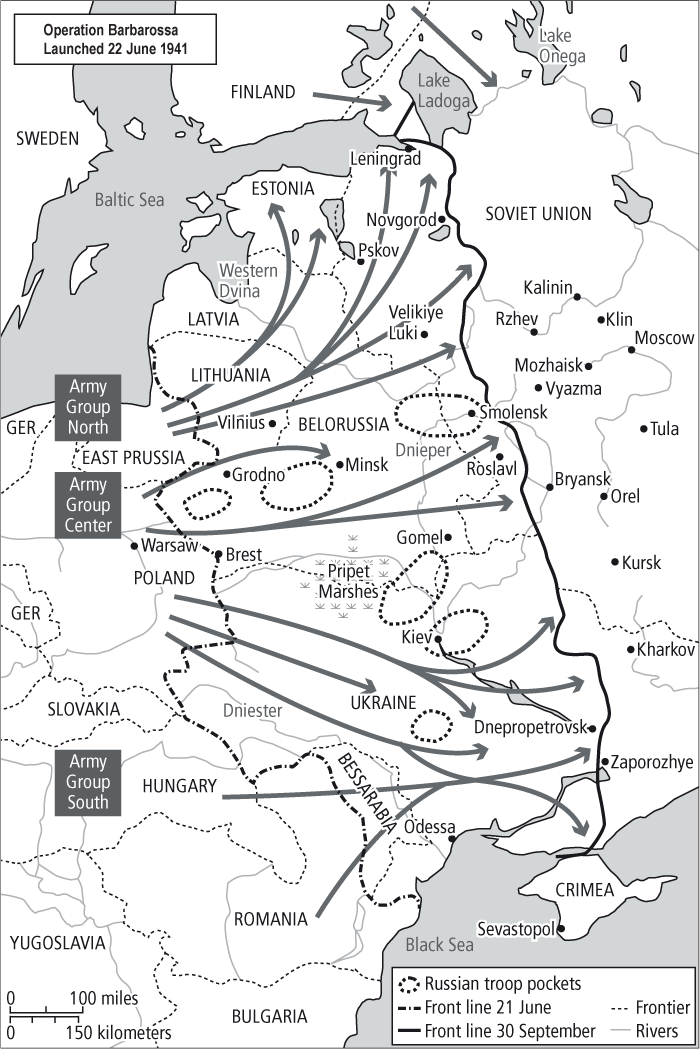

Hitler’s forces stormed across eastern Poland evicting the Red Army, and on into Byelorussia. Army Group North thrust toward Leningrad, Army Group Centre struck toward Moscow and Army Group South cut into Ukraine. To the far south, combined German, Hungarian and Romanian forces drove toward the Caucasus, while to the far north, in Finland, thrusts were made toward Murmansk and down the Karelian Isthmus as part of the ‘Continuation War’. Soviet pre-1939 gains in both Poland and Finland were soon lost.

General Heinz Guderian’s powerful 2nd Panzer Group’s key armoured formations comprised the 24th, 46th and 47th Panzer Corps (which included the 3rd, 4th, 10th, 17th and 18th Panzer Divisions). General H. Hoth’s slightly weaker 3rd Panzer Group included the 39th and 57th Panzer Corps (encompassing the 7th, 12th, 19th and 20th Panzer Divisions). In their path were the Red Army forces of the Western Front’s 3rd, 10th and 4th Armies. They launched a series of desperate, ill-organised and poorly co-ordinated counter-attacks. Their attempts to hold the Germans at bay proved futile as the 3rd and 10th Armies, 6th and 11th Mechanised and 6th Cavalry Corps’ counter-attacks were crushed and Army Group Centre encircled Minsk.

On 22 June, General Kirponos tried to get his 15th and 22nd Mechanised Corps to counter the Germans’ southern and northern flanks. Only a weak element of the 15th Corps’ 10th Tank Division was committed, with little effect, and the Germans penetrated 24 miles to Berestechko. Likewise, the 22nd’s 215th Motorised and 19th Tank Division were unable to prevent the Germans reaching Lutsk. When mustered, the 15th Corps’ weak 10th and 37th Tank Divisions were unable to stop the panzers pushing another 18 miles. Rokossovsky’s 9th and Feklenko’s 15th Mechanised Corps were ordered to counter-attack north of Dubno, while to the south, Karpezo’s 15th and Riabyshev’s 8th Mechanised Corps were also to attack. Unfortunately, Zhukov and Kirponos’ orders led to Vlasov’s 4th Mechanised Corps being dispersed which prevented them from supporting the 8th Corps.

Upon being informed of Hitler’s invasion Churchill unexpectedly changed his opinion of the Red Army. ‘I will bet you a Monkey to a Mousetrap [racing terms for 500:1] that the Russians are still fighting, and fighting victoriously, two years from now.’9 Churchill’s private secretary was so taken aback by this premonition that he wrote, ‘I recorded your words in writing at the time because I thought they were such a daring prophecy, and because it was such an entirely different point of view from that which everybody else had expressed.’10 Only the previous day, his opinion had been that Stalin would be swiftly defeated. It was as if Churchill had foreseen Stalingrad and Kursk.

Churchill went onto the radio to inform the British public that the country had a new ally. Reading between the lines, there is an almost holier-than-thou attitude to his broadcast. He announced:

At 4 o’clock this morning Hitler attacked and invaded Russia. […] All this was no surprise to me. In fact, I gave clear and precise warnings to Stalin of what was coming. I gave him warning as I have given warning to others before. I can only hope this warning did not fall unheeded.11

This was not true. Churchill’s warnings had been so imprecise that they had the reverse effect on Stalin.

Shortly after, Stalin’s main counter-attack was launched on 26 June resulting in a massive battle involving over 2,000 tanks. Confusion reigned. During the fighting the 8th Mechanised Corps was surrounded and the 15th Corps achieved little. In the north, the 19th Corps ran into two panzer divisions and were driven back to Rovno. Rokossovsky conducted his attack on the 27th, only to suffer heavy losses, and was ordered back.

While it was a failure, Stalin’s counter-offensive delayed the Wehrmacht for a week and convinced Hitler he needed to first secure Ukraine, which would have ramifications for Army Group Centre’s drive on Moscow.

Just four days into the invasion, one of the architects of Barbarossa serving with Army Group South was severely wounded in Ukraine. General Erich Marcks, leading the 101st Light Infantry Division in the fighting for Medyka, was hit and lost a leg. He was shipped home and spent a year recovering before being put in the reserves. This gave Marcks ample time to consider the wisdom of Operation Otto. Two of his three sons were to be killed serving on the Eastern Front.

Soviet command and control of the newly instigated armoured formations proved a complete fiasco, thanks to inexperience and the hand of the commissars. ‘I’ve decided to shoot myself,’ Major General Nikolai Vashugin, Commissar of the South-Western Front, told Nikita Khrushchev. ‘I am guilty of giving incorrect orders to the commanders of the mechanised corps. I don’t want to live any longer.’12

He received no sympathy from Khrushchev, who responded, ‘Why are you talking such foolishness? If you’ve decided to shoot yourself, what are you waiting for?’ Vashugin promptly drew his gun and did the deed.

Vashugin’s orders had mattered little, as most of the tank crews were poorly trained and had insufficient ammunition. In many instances, Soviet tanks ran into each other, became stranded in local marshes and swamps, or were abandoned at the roadside by their panic-stricken crews. Most of the older tanks were too thinly armoured and the new T-34s regularly broke down. There was to be no repeat of Khalkhin-Gol, no matter how hard the Red Army tried. They were simply outmatched at every turn.

The Soviet Supreme Command (Stavka), originally employed by Nicholas II during the First World War, was officially set up on 23 June. Timoshenko, Zhukov and Kuznetsov found themselves outnumbered by senior Communist Party officials and old soldiers who had no business running a modern war. Stalin declined the designation of supreme commander, no doubt keen to avoid any blame for the ongoing wholesale destruction of the Red Army. Nonetheless, he continued to act as if he had accepted the role and finally agreed to the formality on 10 July.

Hitler and his staff oversaw the invasion from Forward Headquarters Wolfsschanze (Wolf’s Lair) in the woods at Görlitz, 8km from the town of Rastenburg in East Prussia. He arrived on 24 June expecting it to be state of the art and well located. Instead, the secret complex of bunkers had been built in the middle of an insect-infested forest, which soon made life miserable. ‘I have midge bites all up my legs which are now covered in thick swellings,’ wrote Christa Schroeder, one of Hitler’s secretaries.13

The results of the Red Army’s appallingly bad co-ordination were evident for all to see. Attending Hitler’s situation conferences at Wolfsschanze, Schroeder noted, ‘It is made clear how furiously the Russian fights; he could match us man for man if the Soviets had proper military planning which, thank God, is not the case’.14 Six days into Barbarossa, and Hitler was highly delighted by the rapid progress his armies were making. ‘The boss said this morning that if the German soldier deserves a laurel wreath it is for this campaign,’ observed Schroeder, ‘everything is going better than anticipated.’15

Byelorussia’s capital, Minsk, fell on 28 June to Army Group Centre. With the liquidation of the Minsk pocket, the Germans claimed to have destroyed or captured 4,799 tanks and 9,427 guns and taken 341,000 prisoners of war (POWs). It was a resounding disaster for the Red Army. The subsequent seizure of Smolensk by Army Group Centre yielded similar results and the Germans conducted successful massive encirclements at Vyazma and Bryansk, west of Moscow. On 30 June, Army Group Centre entered Lvov, the Soviet 32nd Tank Division having fled the city and already on the way back to Kiev. Likewise, the rest of Vlasov’s 4th Mechanised Corps were long gone.

Operation Barbarossa, 22 June 1941.

Just as Minsk was falling, Stalin and his cronies met again. The rapid collapse of the Red Army showed the world what damage his wanton persecution of his generals had done. There was an almighty and ugly row, especially after Zhukov suggested the Politburo should leave the generals alone to get on with it. Stalin was furious with Timoshenko for lack of information over the fate of Minsk and reduced Zhukov to tears, accusing him of gross incompetence. Afterwards, getting into their cars, Stalin allegedly sobbed, ‘Everything’s lost. I give up. All that Lenin created we have lost forever.’

Stalin retreated to Kuntsevo, almost certain that the Politburo would depose him. Despite summoning them there on 30 June, Stalin wanted to know why they had come; they reassured him that it was to discuss setting up a government committee on defence with him as head. With the Red Army in disarray and Minsk lost, it is quite possible that Stalin feared for his position, his freedom and, indeed, his life. The cynical might argue that the meeting presented him with an opportunity to flush out any would-be plotters, should his leadership be questioned.

Stalin liked staying at the purpose-built Kuntsevo complex because he felt safe there. Surrounded by thick woods, it was fenced in and had a heavily armed special security detachment. Despite being a dacha and single storey, it was quite palatial compared to most summerhouses retained as holiday residences. It was so close to the Kremlin that Stalin’s inner circle dubbed it ‘Nearby’, while his dacha at Semyonovskoe was known as ‘Distant’, or ‘Faraway’. At the end of the day he regularly returned to Kuntsevo rather than remain in his flat in the Kremlin. The emotionally detached Stalin normally slept completely alone in the main house with the guards and servants housed elsewhere. If anyone stayed, it was usually in the guest villas. Such was the life of ‘the Boss’.

Partially reassured, Stalin returned to the Kremlin on 1 July. He finally made a long, rambling public radio announcement two days later; his heavy breathing and constant gulping of water betrayed his anxiousness. It was a historic moment, as Stalin had not made a live radio broadcast since 1938 – he had only addressed Communist Party gatherings or his speeches had been pre-recorded.

Stalin indignantly laid the blame for the destruction of the Red Army at the feet of Britain and America because they had not opened a second front against Germany. The other reason, he said, was the lack of tanks and aircraft. The first claim was ridiculous because Britain and America were simply not in a position to open a second front. Once Japan entered the war later in the year things would go badly for them in the Far East and the Pacific. In addition, Britain was only just holding on in North Africa. The second claim was an outright lie.

However, Stalin did publicly own up to the terrible calamity that was facing the nation:

In spite of the heroic resistance of the Red Army, and although the enemy’s finest divisions and finest air force units have already been smashed and have met their doom on the field of battle, the enemy continues to push forward, hurling fresh forces into the attack.

Hitler’s troops have succeeded in capturing Lithuania, a considerable part of Latvia, the western part of Byelorussia, part of western Ukraine. The fascist air force is extending the range of operations of its bombers, and is bombing Murmansk, Orsha, Mogilev, Smolensk, Kiev, Odessa and Sebastopol.

A grave danger hangs over our country.16

Even Gulag prisoners got to hear Stalin’s frank admission. Gustav Herling, in a labour camp near Archangel, noted, ‘It was the speech of a broken old man; he hesitated, his choking voice was full of melodramatic overemphasis and glowed with humble warmth at all patriotic catchphrases’. It gave Herling and the other prisoners warped hope, ‘Millions of Soviet slaves prayed for liberation by the armies of Hitler’.17

Following Stalin’s radio address, it is doubtful that Hitler, Brauchitsch, Halder, Jodl, Keitel or Marcks quite realised the enormity of what they had done with Barbarossa. The Soviets did – even at street level. ‘A Russian girl told me today, and it is typical of the sidewalk conversation,’ said Erskine Caldwell, a US citizen living in Moscow, ‘that winning this war was now the sole objective of her life. If there is any such thing as so-called total war, this is to be it.’18

Stalin’s vice-like grip on power was such that there would be no dramatic fall from grace. The army was preoccupied and he had Beria’s NKVD guarding his back. Voroshilov and Zhukov were sent to the front to try and make sense of the developing chaos and stabilise the situation using whatever methods necessary. This also conveniently served to get his two most senior officers out of Moscow.

In the wake of the Red Army’s disintegration, Stalin was determined to stop the rot and reverted to his favourite tactic. The Soviet leader warned, ‘There must be no room in our ranks for whimperers and cowards, for panic-mongers and deserters. […] We must wage a ruthless fight against all.’19 In military terms, the meaning was clear.

The Red Army’s failures in the summer of 1941 unleashed a second round of purges. Front, corps, army, divisional and unit commanders were arrested and sent to the firing squad. The NKVD was instructed to shoot every coward, deserter, self-inflicted wounded and shell shock victim they could lay their hands on. It was also made clear that deserters’ families would be punished as well. Stalin issued an order that stated, brutally but simply:

Anyone who removes his insignia during battle and surrenders should be regarded as a malicious deserter, whose family is to be arrested as a family of a breaker of the oath and betrayer of the Motherland. Such deserters are to be shot on the spot. Those falling into encirclement … and who prefer to surrender are to be destroyed by any means.

The most prominent victim of Stalin’s second round of self-inflicted bloodletting was General Pavlov, commander of the Western Military District, followed by Generals Klimovskikh and Klich on his staff. The irony was that Pavlov had indeed contributed to the Red Army’s disastrous performance against the Wehrmacht. Pavlov was a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, where he had drawn the wrong conclusions about the use of tanks. He had advocated the French doctrine, whereby armour was used in direct support of the infantry. Voroshilov, eagerly looking to discredit Tukhachevsky’s ideas on massing armour, had seized upon this.

Rather than trying to consolidate its precarious position, the Red Army continued to prematurely squander its reserves with ill-fated counter-attacks. Stavka’s first counter-strikes saw Lieutenant General P.A. Kurochkin’s 30th Army launch the newly arrived mechanised corps at Hoth’s 3rd Panzer Group in Byelorussia. In five days of fighting near Senno and Lepel they lost 832 of their 2,000 tanks. This left the Germans free to press on toward Smolensk.

In a desperate move to restore the situation along the Dnepr, Zhukov had instructed Timoshenko’s Western Front to conduct counter-attacks along its full length. Timoshenko did this on 6 July, when he threw the 6th and 7th Mechanised Corps, with a total of 700 tanks, at the flanks of the German 39th Panzer Corps north of Orsha. Lacking air cover, they headed for Senno and came across the 17th and 18th Panzer Divisions. A week later, a German breakthrough heralded the encirclement of Smolensk and another 300,000 Soviet troops were cut off between the city and Orsha.

During the first eighteen days of the war, the Soviet Western Front, defending eastern Poland and western Byelorussia, lost more than 417,000 men, killed, wounded or missing, as well as 9,427 guns and mortars, more than 4,700 tanks and 1,797 aircraft. Such terrible losses, though, could be replaced, as over half a million people rallied to the Red Army ranks and about 2 million citizens worked on the construction of defensive zones.

Then, on 14 July 1941 the Red Army took the first very tentative steps toward victory with the official creation of the Reserve Front. This finally formalised Timoshenko and Zhukov’s efforts to create a sizeable reserve force and it totalled around forty divisions organised into six armies. These most likely drew on some of the eighty-eight divisions which were still forming earlier in the year.

The reserve armies were initially under General I.A. Bogdanov, until Zhukov personally assumed control. It should be borne in mind that victory was far from assured at this stage and much could, and did, go wrong in the coming months and years for Stalin and his generals.