1 |

BEFORE THE EMPIRE |

UNTIL THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, ‘Germany’ was simply a large number of separate political entities, whose status and combinations changed over time, and ranged from city-states through to a number of fully-fledged kingdoms. Until 1805, most had belonged to the increasingly-nominal Holy Roman Empire, which had been replaced during 1815 the Congress of Vienna by a loose German Confederation (Deutsches Bund) of thirty-nine states, to which six more were subsequently added. A progressive customs union (Zollverin) gradually brought the states closer together, and the short-lived Frankfurt National Assembly that had been established in the wake of the 1848 revolutions attempted to make this into a formal empire. The failure of this initiative, and the ephemeral Erfurt Union, which foundered through Austrian opposition, led the loose Confederation to continue to exist until 1866.

That year, the Austro-Prussian War led in 1867 to the winning Prussian-led alliance forming the North German Confederation (Norddeutscher Bund), excluding Austria, Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden and their allies. In 1870, the Franco-Prussian War led to Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden joining the grouping, which was proclaimed the German Reich at Versailles on 18 January 1871, comprising twenty-seven constituent territories, with the imperial dignity vested in the kings of Prussia.

Of the German states, only Prussia had made intermittent attempts at maintaining a navy.1 These were consolidated after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, while 1848 and 1852 there existed a Reichsflotte, created under the auspices of the Frankfurt National Assembly, which was, however, dissolved in April 1852; although most ships were sold into merchant service, two frigates (one steam, one sail) passed to the Prussian Navy. The latter force was then developed by Prince Adalbert of Prussia (1811–73), Commander-in-Chief from 1854 to 1870, including the establishment of the naval bases of Kiel in 1865 and Wilhelmshaven (in an enclave within the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg) in 1869, and the steady purchase of frigates and smaller vessels. It was as the sole naval force within the new North German Confederation that the Prussian Navy transitioned to being the new (albeit Prussian-led) Federal Navy on 1 October 1867, the navy henceforth remaining a ‘German’ institution, in contrast to the armies at the disposal of the Confereration and later Empire, which remained in the ownership of the individual states.

The ‘new’ fleet was accompanied by a new Fleet Plan, a modification of plans put forward by the Prussian Navy in 1862 and 1865 (and rejected by the Prussian Landtag [State Parliament]). The 1867 Plan, however, was approved by the new Reichstag [Reich Parliament], and envisaged a fleet of sixteen armoured ships, twenty unarmoured corvettes and eight avisos, plus twenty-six gunboats and auxiliaries, by 1877, to provide both a home and a foreign force. As compared with the 1865 iteration of the Plan, there were four less armoured ships and six more corvettes, a change opposed by Prince Adalbert, and reflecting what would be an ongoing debate regarding the balance to be struck between building and maintaining a home battlefleet and doing the same for a cruising force capable of world-wide deployment.

Arminius

A number of other lesser naval powers acquired armoured vessels in the wake of the adoption of the type by the French and British navies, and the proof of the concept of armoured warships during the American Civil War.2 Like her particular rival at the time, Denmark (against whom wars were fought over the ownership of Schleswig-Holstein during 1848-51 and again in 1864), Prussia bought a small twin-turreted ironclad from a British shipyard, in this case Samuda Bros. of Poplar, on the Thames; the very similar Danish Rolf Krake3 came from Napier, on the Clyde.

The Prussian vessel, named Arminius, had been laid down in 1863 on speculation by the shipyard (perhaps with an eye to the Confederate States of America [CSA], which was attempting to acquire ships in Europe at the time),4 her purchase by Prussia being partly financed by popular contributions. Her design was by Captain Cowper Phipps Coles, RN (1819–70), and mounted two examples of his pattern of turret, apparently intended to be equipped with a pair of Armstrong 68pdr/8in [20.3cm] MLRs. However, she was actually armed with Krupp BLRs, possibly first with 21cm/12.25s before finally receiving 21cm/19s. The protection of her iron hull was mounted on a 229mm teak backing, and comprised wrought iron 114mm thick, tapering to 76mm fore and aft. The turrets varied from 114mm to 119mm in thickness, while the conning tower carried 114mm plate. Arminius had four transverse trunk boilers, with a 2-cylinder horizontal engine, rated at 1200ihp, giving a speed of around 10kts. Although it had been hoped that she would be ready by September 1864, Arminius was not delivered in time owing to the Second Schleswig War with Denmark. On 3 October 1866, the ship undertook a comparative trial with the visiting US monitor Miantonomoh in Kiel, Arminius proving the faster by two knots.

Arminius as completed, with her bulwarks raised. (BA 134-B0164)

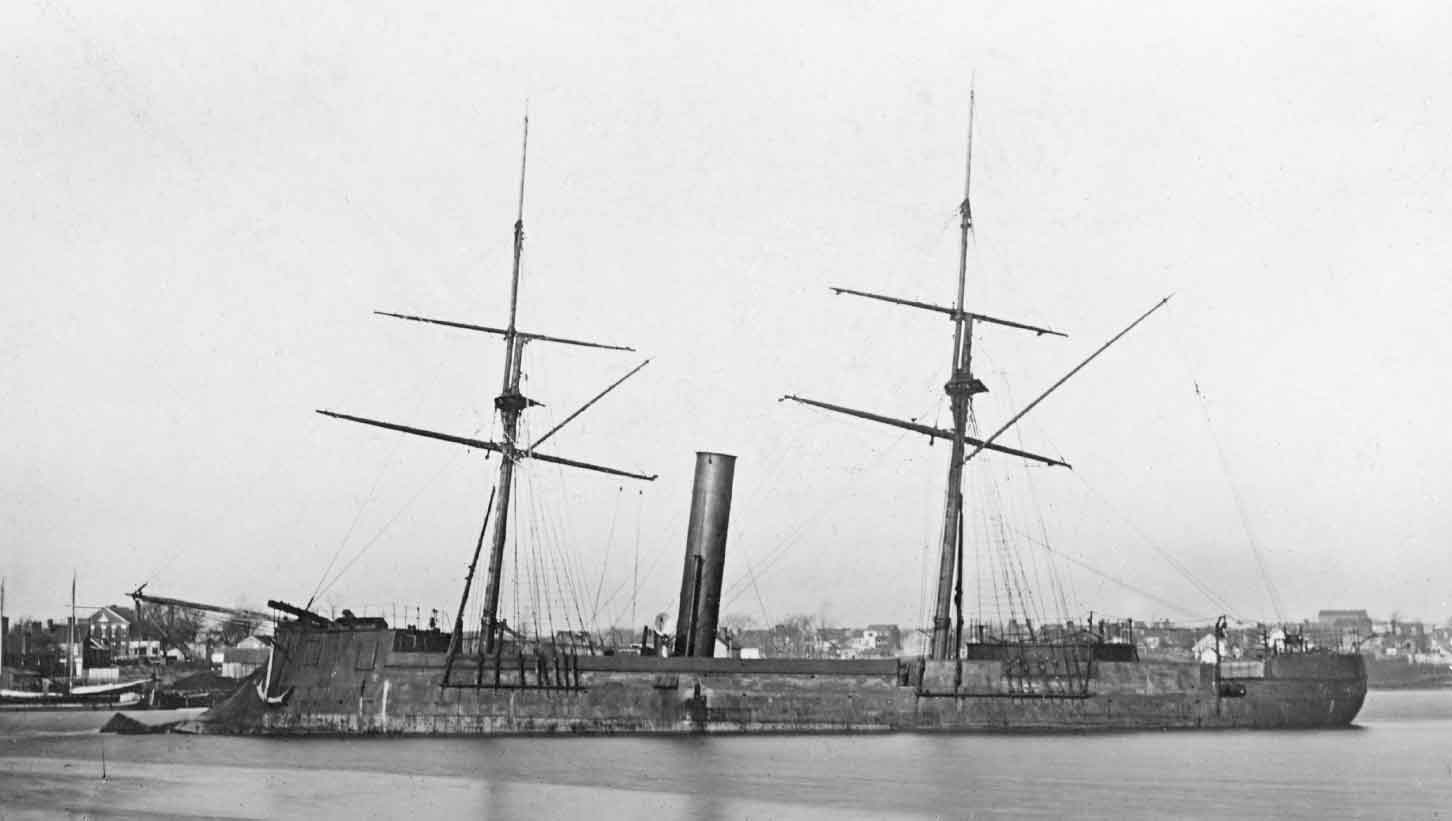

The monitor USS Miantonomoh at Kiel at the time of her trial run against Arminius. (NHHC NH 46259)

The ship was given a topsail schooner rig, with masts at the extremities of the hull, they and their shrouds obstructing the firing arcs of the turrets. However, it proved impossible to steer the ship under sail, and the rig was removed at her first refit.

Prinz Adalbert

The year after Arminius had been ordered, the opportunity arose to buy another ironclad when the French shipbuilder Lucien Arman was ordered by Emperor Napoleon III to put up for sale two ships allegedly being built for Egypt – but really ordered by the CSA, and under an embargo since February. Initial negotiations for their disposal had actually begun in December 1863, when the Danes were approached by the French.5 Denmark initially intended to buy both ships,6 but in the event sufficient funds were available for only one, ‘Sphinx’, a contract being agreed on 31 March 1864. Two months later, on 25 May, the Prussians purchased ‘Cheops’, ships belonging to each of the combatants in the Second Schleswig War (February–August 1864) thus being built alongside each other at Bordeaux.

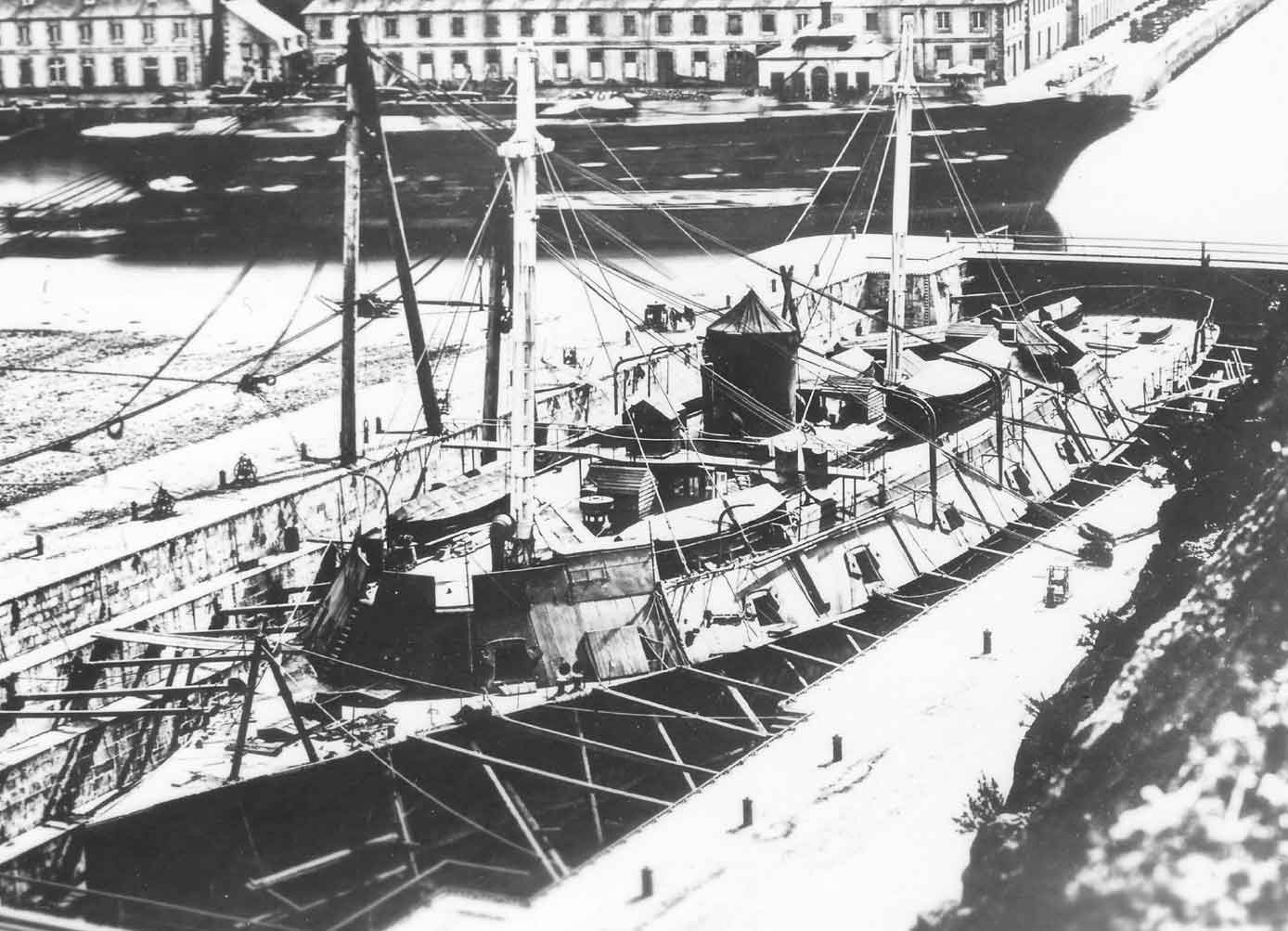

The Confederate ram that Prussia did not buy: ‘Sphinx’, which briefly flew the Danish flag as Stærkodder, before being transferred to her original owners, taken over by the United States at the end of the Civil War (and laid up at Washington, where she is seen here) and finally sold to Japan as Kötetsu, later Azuma. (NHHC NH 43994)

The Danish half-sister, now named Stærkodder, was subject to various contractual terms that the builders found difficult to fulfil, and negotiations continued even after the ship had sailed from the shipyard in October, arriving at Copenhagen on 10 November. Although some trials were carried out, the ongoing negotiations broke down, possibly influenced by the technical assessment of the ship by the Danes, not to mention the end of the war with Prussia, and in January she was handed over to the CSA in Danish waters, becoming CSS Stonewall.7

Prinz Adalbert in 1870. (BA 134-C0066)

The Prussian purchase was at one point cancelled, but reinstated in January 1865, and delivered as Prinz Adalbert in October. She was very different from Armenius, being wooden-hulled, with tumblehome sides and a huge ram. In contrast to the revolving turrets of the British-built vessel, there were fixed box-batteries at the bow and on the after deck, with guns (one in the forward battery, two in the mid-ships one) on mountings that allowed them to fire through a chosen port. On the other hand, there were twin shafts and rudders to ensure good manoeuvrability.

When the ship arrived in Prussia, she was immediately rearmed with Krupp guns. She also proved to be in poor material condition, with significant leakage, her defects requiring a reconstruction at Geestemünde during 1868/69, including re-fitting the armour. Other changes carried out in Prussia included moving the mainmast further aft (the ship was in any case useless under sail). However, unsound timber severely truncated her service life, being outlived by Arminius by a quarter-century.

Friedrich Carl and Kronprinz

Both Arminius and Prinz Adalbert were primarily suitable only for coastal waters. In contrast, the next ironclads acquired by the Prussian Navy were fully seagoing vessels, which in the context of the 1860s meant rigged vessels armed on the broadside, the type that comprised the bulk of new construction by Great Britain and France.

It has been recognised that the defence of Prussian interests required more vessels to be added to the navy, capable of countering potential enemies, in particular the Danes, opposing any landings and breaking a blockade. As noted above, a fleet plan had been put to the Prussian Landtag in 1865, but rejected; it was therefore necessary to issue a royal decree on 4 July to set a Navy budget that included funds for two armoured frigates, one to be built in Great Britain and one in France, each vessel being some four times larger than Arminius and Prinz Adalbert.

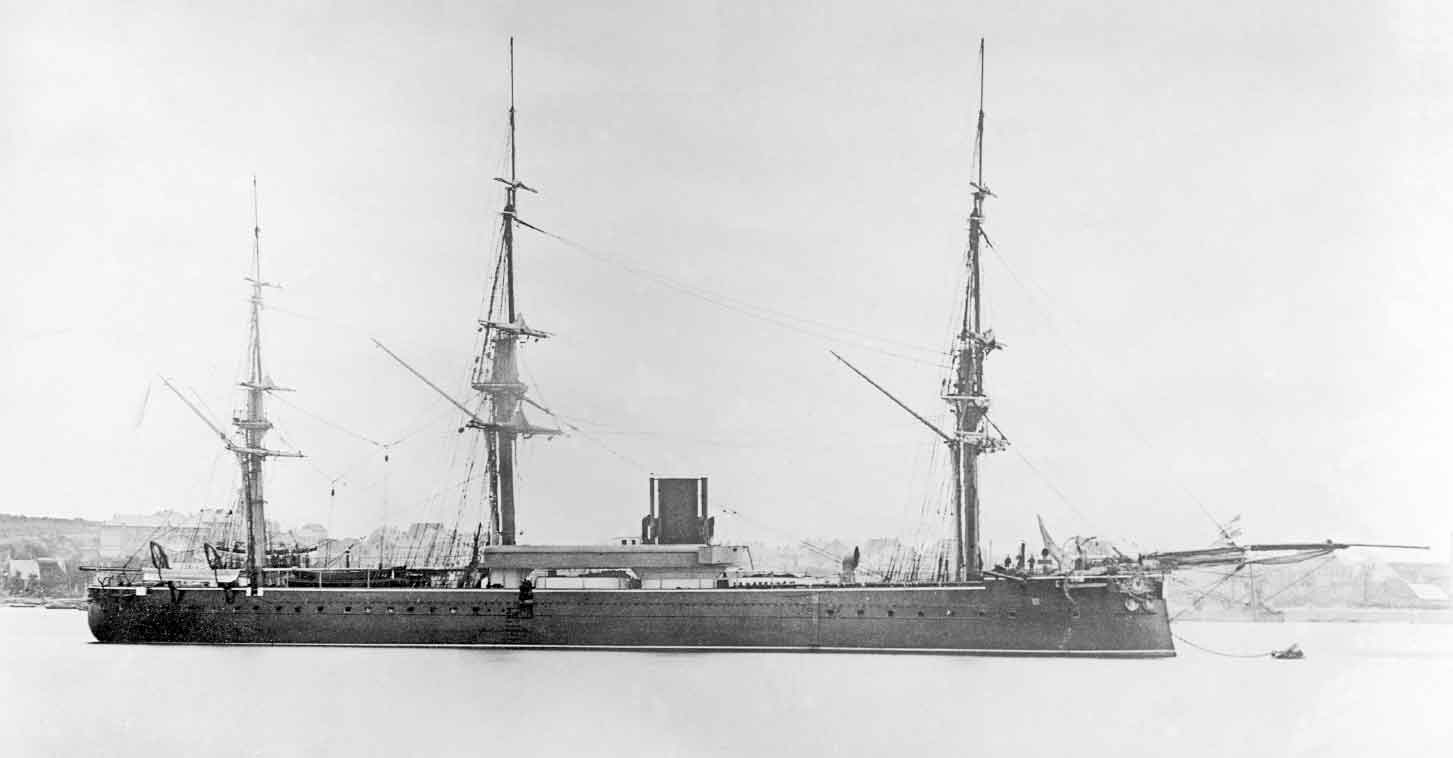

Friedrich Carl in 1867. (Author’s collection)

The first order was placed for the French-built Friedrich Carl, on 9 January 1866, followed four days later with that for Kronprinz, from Arminius’ builder and designed by the British Royal Navy’s Chief Constructor, (Sir) Edward Reed. Both ships were of similar size, protection and capability, although as designed Kronprinz had a slightly heavier armament (thirty-two, as against twenty-six, 72pdrs) and was significantly faster; on the other hand, Friedrich Carl spread more canvas. In practice, both came into service armed identically with Krupp breech-loading guns, albeit after a significant period laid up without armament, owing to a breech failure during a series of trials held in 1867/68. This led to the rejection of guns fitted with the then-standard Kreiner breech and a delay until new weapons with a new breech of Krupp design were available.

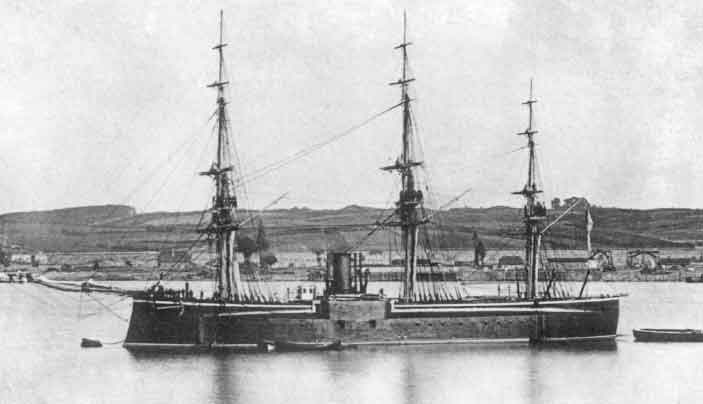

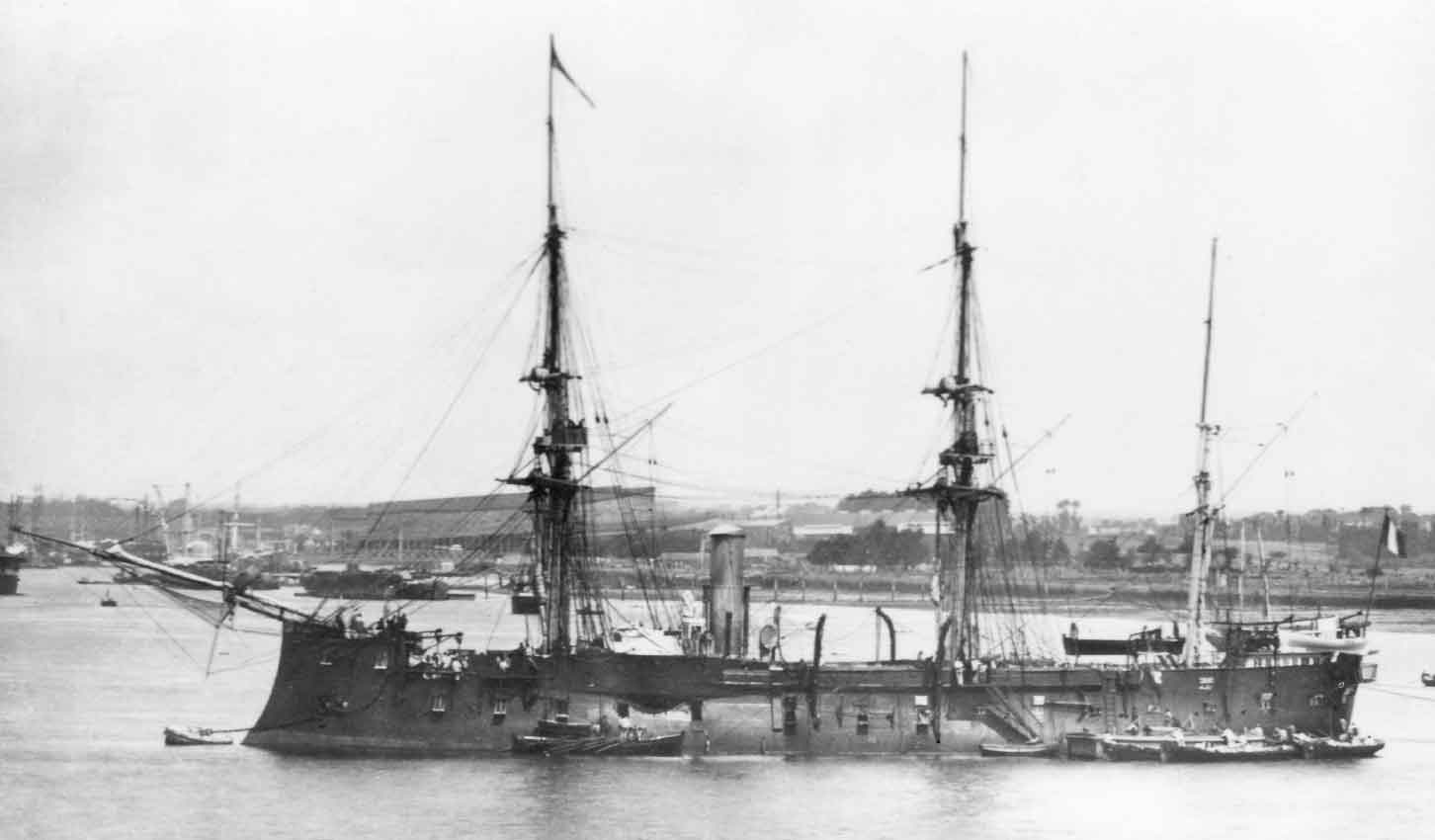

Kronprinz as completed. (Author’s collection)

Thus, Friedrich Carl, first commissioned in France in October 1867 (her crew, and that of Kronprinz having been ferried from Germany in the corvettes Hertha and Medusa, while en route to the Mediterranean), lay idle in Germany for nearly two years until her guns became available in July 1869. Similarly, Kronprinz, commissioned at Portsmouth in September 1867, arrived at Kiel on 28 October 1867, only to pay off on 1 November to await the delivery of her guns. It was not until the 11 May 1869 that she was able to recommission. When they entered service, the two ships mounted sixteen 21cm guns, fourteen 19-calibre weapons in the battery, with two 21-calibre pieces as bow- and stern-chasers. Protection comprised complete waterline belts, thinning at the ends, extended upwards at full thickness over the battery.

In size, armament and most other aspects they were very similar to the British Defence and Hector classes, laid down in 1859 and 1861, respectively, and the French Couronne. The British vessels represented diminutives of the original ironhulled ironclad, HMS Warrior (launched 1860), and had from the outset been regarded as second-class vessels in Great Britain. Couronne was, on the other hand, representative of the size of the vast majority of contemporary French ironclads – and was the only iron-hulled example, the wooden hulls of the remainder (including the two somewhat larger Magenta class) significantly reducing their survivability and durability as compared with iron-built vessels. Kronprinz had an unusual bow, in that while she had the usual ram bow of the era, a false stem was fitted around the slope above water, giving the impression of a vertical stem.

The Austro-Prussian War

While these new seagoing ironclads were still under construction, Prussia went to war again, in this case against Austria. When the conflict erupted in mid-1866, Arminius and Prinz Adalbert were at Kiel, but the former was rapidly sailed via the Skagerrak and the Kattegat to Hamburg, covering the 1740km in 100 hours, giving an average speed of 9.2kts.

She was based for the rest of war at Geestemünde, in particular operating against the forts of the Austrians’ ally, Hanover, at the mouth of the Weser, and covering, with the wooden gunboats Tiger and Cyclop, the crossing of the Elbe by the Prussian army, to attack the city of Hanover itself. Arminius underwent a major refit after paying-off in November 1868, being stripped of her sailing rig and having a flying-deck erected from behind her fore-turret to the stern, with ventilators led up to that level, and pole-masts rigged. The main mast was removed altogether in 1870.

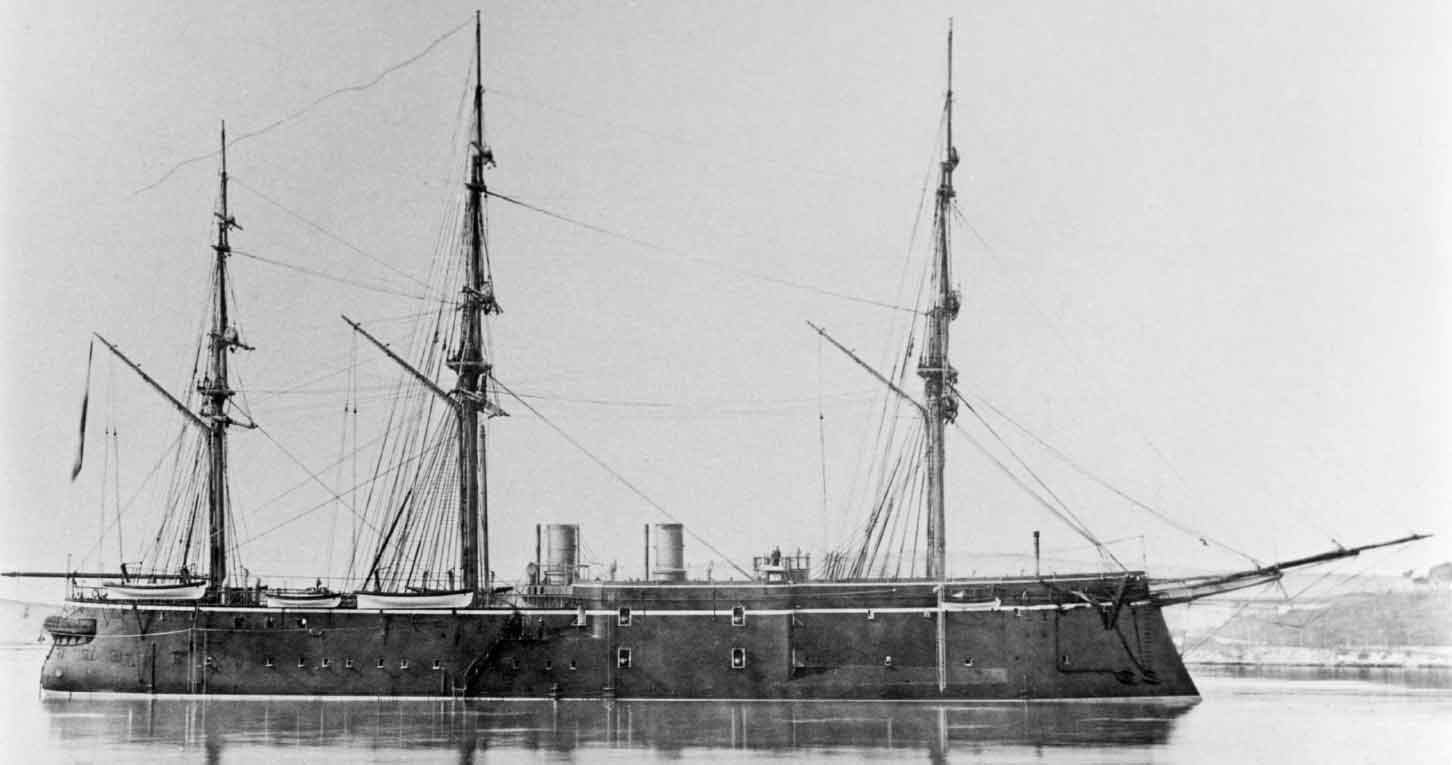

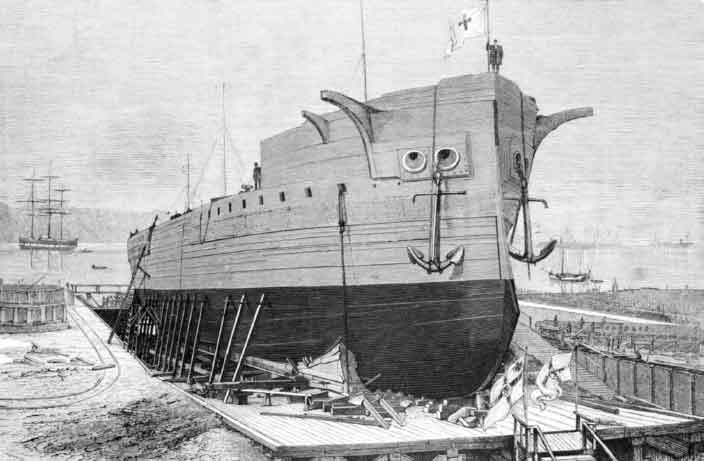

König Wilhelm as completed. She had been laid down for Turkey. (BA 134-B0171)

König Wilhelm

As compared with the second-class vessels upon which Friedrich Carl and Kronprinz had been modelled, the larger British ironclads (the Warriors, Achilles and Minotaurs) displaced between 9300t and 10,900t. In 1866, the opportunity arose for Prussia to acquire a ship of this class, when the impecunious Ottoman authorities put up for sale their Fatih, building at the Thames Iron Works. Prussia bought her on 6 February 1867, initially under the name Wilhelm I. However, this was changed in December to König Wilhelm, the ship being launched under that name the following April. Another potential purchase in the spring of 1867 was of the American Dunderberg which was, however, actually acquired by France as Rochambeau,8 and would operate against Prussia during the forthcoming Franco-Prussian War.

On completion, König Wilhelm was popularly regarded as the most powerful warship in the world, being compared favourably with HMS Hercules, which was some 1800t smaller and 10m shorter, and has a smaller number of guns.9 König Wilhelm’s great size was initially a problem, as no dock in Germany was big enough to take her; she thus had to make a run to Britain in August 1869 for her bottom to be cleaned. It subsequently proved possible to dock her (with difficulty) at Wilhelmshaven, but it was not for some time that the development of the German dockyards meant that they could easily take ships of her dimensions. The constraints of existing dry-docks were always an important issue in the development of new generations of ships, a good example being that of French dreadnoughts in the years prior to the First World War,10 and in designing the final generations of Imperial German capital ships during 1916–18 (see p 126).

The former US ironclad ram Dunderberg (1865), which was another potential Prussian purchase of surplus foreign-built materiel; in the event, however, she was purchased by France, as whose Rochambeau she is seen here. (Author’s collection)

Like Kronprinz and Friedrich Carl, König Wilhelm was originally to be armed with 72pdrs (in her case thirty-three), but was actually fitted with eighteen 24cm/20s on the gun-deck and five 21cm/22s. Also as with earlier ships, there were delays in the provision of weapons, and she was still not fully armed in September 1869, seven months after commissioning. Three of the 22cal weapons were mounted in a forecastle armoured battery and the other two in a pair of upper deck armoured batteries in the rear waist at upper deck level. These latter were protected with 152mm plating, the battery-deck itself and belt having 203mm armour, tapering to 152mm fore and aft, on 560mm of teak, itself on the 50mm-thick hull shell.

Hansa

The concept of the armoured corvette Hansa went back to 1861, with a focus on service against shore fortifications, but it was not for some years that she was built, as the first armoured ship to be built in Germany.11 However, when the ship was actually begun in at Danzig Dockyard in November 1868, it was to a Reed design, not dissimilar to HMS Pallas, launched in 1865; like her, Hansa had a wooden hull, but was slightly larger and more heavily armed.

Hansa as completed. (Author’s collection)

In Pallas and the contemporary, but much bigger, ironhulled HMS Bellerophon, Reed had introduced the central-battery concept, with the armament placed in an armoured box amidships, rather than simply spread along on a gun deck. Hansa had in addition an upper battery arranged for axial fire, much like the British Audacious class (1869/70). Hansa was launched in October 1872, and in August of the following year was towed to Stettin for completion by AG Vulcan, work there finishing in December 1874, before transfer to Kiel on 3 January 1875, for final fitting-out in a floating dock.

The Preußen Class

The navy’s first uniform class of capital ships, all built in home yards, was originally intended to follow previous German armourclads in being broadside-armed, the new Austro-Hungarian central-battery ship Custoza12 being regarded as a model. This ship had a double-storey battery, designed to maximise axial fire. However, after the first vessel, Großer Kurfürst, had already been laid down, the design was entirely recast as a turret-ship similar in layout to HMS Monarch, with Coles-type twin turrets on a low hull, but built-up fore and aft for seaworthiness (as carrying a full sailing rig), the deck-lines of the forecastle and poop being extended along the mid-length by hinged bulwarks, as in many other similar vessels of the period. To make up for the lack of ahead fire of the turret-mounted 26cm/22 guns, chase pieces of 17cm/25 calibre were fitted in forecastle and poop.

The turrets were steam-powered and mounted on what would originally have been the battery deck. The faces of the turrets were 260mm thick, the remainder having 210mm armour. The hull armour at the waterline midships was 235mm for a single plate’s width, thinning to 185mm below the waterline and 210mm above, all thinning to 105mm at the ends. All armour was mounted on a wooden backing.

As with Hansa, the inexperience of the yards – Großer Kurfürst was the first product of the new dockyard at Wilhelmshaven and Friedrich der Große the second to be laid down in the yard at Kiel – resulted in extended building times, exacerbated in the case of Großer Kurfürst by the need to alter her design on the stocks. Indeed, the first to be launched and to complete was the privately-built Preußen, a year ahead of the state-built Friedrich der Große.

The Austro-Hungarian casemate ship Custoza (laid down in 1869), the original model for the Preußen class. (NHHC NH 87042)

To the Dawn of the Empire

On commissioning, König Wilhelm became flagship of an evolutionary squadron that also comprised Kronprinz and Friedrich Carl, which undertook exercises with various other ships during August/September 1869. The following May, the same ships, plus Prinz Adalbert, were proceeding on a visit to Great Britain when Friedrich Carl damaged her screw by grounding in the Great Belt and had to be repaired at Kiel, rejoining her squadron-mates at Plymouth. Here they were formally constituted as a training squadron on 1 July, sailing for the Azores. However, with an increase in tensions with France, Prinz Adalbert was recalled to Dartmouth to remain in contact with events. The remainder of the squadron joined her on 13 July and, war being considered imminent, sailed for home, arriving on the 16th – Prinz Adalbert in the tow of Kronprinz, owing to her lack of speed.

War broke out with France on 19 July 1870, ostensibly over a diplomatic slight to the French Emperor Napoleon III in the wake of a dispute over the future occupant of the throne of Spain, but in reality the culmination of pressures arising from the progressive unification of Germany that was felt to threaten French interests. Although on land the French army was a third the size of the forces available to Prussia, the North German Confederation and the southern German states (which formally joined the Confederation November), all of whom allied against France, the French Navy was vastly superior to that of Prussia, and rapidly imposed a blockade of her coasts.

Friedrich der Große on the stocks at at Kiel; in the left background is the Russian frigate Svetlana, and on the right Kronprinz and Nymphe (i). (Die Gartenlaube [1874], p.715)

The Prussian Navy’s larger ironclads, Friedrich Carl, Kronprinz and König Wilhelm, were based at Wilhelmshaven from the outset, but Arminius was forced to break through the blockade to the North Sea from Kiel by exploiting her shallow draught to sail through coastal waters, and shook off an attempted interception by three French armoured frigates. Prinz Adalbert and three small gunboats were also available, but the ironclad was unsuitable for seagoing operations and served as the Elbe guardship throughout the war.13

Preußen as built. (BA 134-C0072)

Atalante (1868), one of the ships deployed by the French in German waters during the Franco-Prussian War. (Author’s collection)

The French were unable, in spite of their superior numbers, to make any attack on the Prussian naval bases, and largely contented themselves with taking up a blockading station off Heligoland. The Prussians made a number of sorties into the North Sea, but after the first, in early August 1870, by Arminius, Friedrich Carl, Kronprinz and König Wilhelm, engine problems suffered by the latter three meant that Arminius for a time became the principal combat unit, the ship sortieing over forty times. However, action was limited to a single brief skirmish with the French armoured frigate Gauloise and the armoured corvette Atalante off Heligoland. On 11 September, the three Prussian frigates joined Arminius on another sweep, but no French ships were encountered, as the French Navy withdrew its ships in September, following their army’s defeat at Sedan and the capture of Napoleon III. The war continued, however, into the New Year, and it was proposed that a newly-overhauled Kronprinz should undertake a raid on Cherbourg in early February; however, the armistice, signed on 28 January 1871, came before the attack could take place.

It was on 10 December 1870 that the North German Confederation was renamed the German Reich, with Wilhelm I of Prussia as its Emperor, as formally proclaimed at Versailles on 18 January 1871 during the siege of Paris that marked the last four months of the war. As well as the consolidation of all German states except Austria into one political entity, the war also resulted in the transfer of the most of the province of Alsace, and a quarter of Lorraine, to the German Empire under the direct rule of the Reich Government, not any of the States. The existence of Alsace-Lorraine within the German Empire would remain a running sore in Franco-German relations.

1. On the history of the Prussian and German navies down to the 1890s, see L Sondhaus, Preparing for Weltpolitik: German Sea Power Before the Tirpitz Era (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1997).

2. For a well-illustrated account of the first generation of armoured ships, from Arminius to the Kaiser class, see Schenk, Nottelmann and Sullivan, ‘From Ironclads to Dreadnoughts: The Development of the German Navy 1864-1918, Part I: The First German Armored Ships – The Foreign-built Ironclads’.

3. A A Putnam, ‘ROLF KRAKE, Europe’s First Turreted Ironclad’, Mariner’s Mirror 84/1 (1998), pp 56–63; H C Bjerg, ‘When the Monitors Came to Europe: The Danish Monitor Rolf Krake, 1863’, International Journal of Naval History 1/2 (2002).

4. See D M Sullivan, ‘Phantom Fleet: The Confederacy’s Unclaimed European Warships’, Warship International 24 (1987), pp 13–32.

5. R S Steensen, Vore Panserskibe (Copenhagen: Marinehistorisk Selskab, 1968), pp 178–95.

6. The Danes also acquired a Confederate ironclad building on Clydeside, which became Danmark.

7. Arriving in American waters too late to play an active role in the Civil War, she passed into Union hands, and was then sold to Japan as Kotetsu, later Azuma; she remained in service until 1888 and was broken up twenty years later.

8. S S Roberts, ‘The French Coast Defence Ship Rochambeau’, Warship International 30 (1993), pp 333–45; W H Roberts, ‘“Thunder Mountain”: The Ironclad Ram Dunderberg’, Warship International 30 (1993), pp 363–400.

9. See, e.g., a report on her trials in The Engineer 27 (1869), pp 156–7.

10. This meant that the Courbet and Bretagne classes were restricted the same hull dimensions, with the Normandies only slightly more, with negative impacts on their capability.

11. For a well-illustrated survey of German-built capital ships from Hansa to Oldenburg, see Schenk, Nottelmann and Sullivan, ‘From Ironclads to Dreadnoughts: The Development of the German Navy 1864-1918, Part II: The German-built Ironclads’.

12. R F Scheltema de Heere, ‘Austro-Hungarian Battleships’, Warship International 10 (1973), pp 21–31.

13. See C Jones, ‘The Limits of Naval Power’, Warship 2012, pp 162–8 for a full account of the Franco-Prussian naval war.