6 |

WAR – I |

Operations 1914–1916

MOBILISATION

For Germany, the First World War began1 with her declaration of war on Russia on 1 August 1914 and on France two days later. Following Germany’s invasion of Belgium on 4 August, the United Kingdom declared war on Germany at midnight that day; Japan did so on the 23rd, in accordance with the terms of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance.

Immediately before mobilisation, the High Seas Fleet comprised twenty-one battleships and four large cruisers, as compared with twenty-eight battleships, five battlecruisers (three more were in the Mediterranean, and another in the Pacific) and four big armoured cruisers in the British Home Fleet (expanded into the Grand Fleet on mobilisation). In both fleets, eight of the battleships were pre-dreadnoughts, although the British examples (King Edward VII class) had 9.2in [234mm] intermediate batteries.

As far as reinforcements in immediate prospect were concerned, the British had two battleships (Benbow and Emperor of India) and one battlecruiser (Tiger) completing fitting-out (they commissioned on 7 October, 10 November and 3 October, respectively), while two more battleships were requisitioned from Turkish contracts (Agincourt [7 August] and Erin [22 August]). There were also eleven battleships under construction and due for completion during 1915/16 (five Queen Elizabeth class, five Royal Sovereign class and the ex-Chilean Canada).

On the other side of the North Sea, the three remaining Königs were due to commission before the end of the year, Kronprinz being the last, in November, although she did not complete trials until early 1915. Derfflinger was also nearly ready, commissioning on 1 September. However, only three ships (Bayern, Baden and Lützow) were in realistic prospect for 1915/16, with two other ships (Sachsen and Hindenburg) on the slip and scheduled for 1917, and one (Mackensen) programmed, but not yet laid down (for the war construction programme, see pp 124–7, below). In addition to the numerical deficit, there was a further issue in that ten of the British 1915/16 ships were armed with 15in [380mm] guns, while this was only the case for two of the German ones (plus one of the later ones).

The intention had been that the last Königs would replace the remaining Braunschweigs (Lothringen, Preußen and Hessen) in the High Seas Fleet, but with the coming of war, all were retained in the II. Sqn. The I. Sqn continued to accommodate the Nassaus and Helgolands, with the most modern battleships concentrated in the III. Sqn. With mobilisation, three further squadrons of battleships were provided from reserve, the Wittelsbachs, together with Braunschweig and Elsaß, becoming the IV. Sqn, and the Kaiser Friedrich IIIs the V. Sqn along with the two remaining Brandenburgs, while the Siegfried and Odin classes formed the VI. Sqn. Of the older large cruisers, the Victoria Louises became the V. SG, the remainder being grouped into the IV. SG (redesignated III. SG on 28 August), except for Fürst Bismarck, which did not finish her reconstruction until mobilisation was complete – and by which time some of the older ships brought forward were already being paid off. Thus, as soon as she had completed her post-refit trials, Fürst Bismarck was used briefly as mobile target for torpedo trials, and then reduced to a stationary training ship.

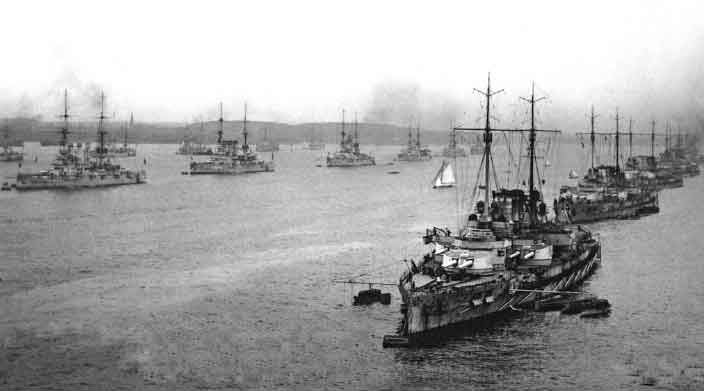

The fleet at Kiel around 1912; on the left are Moltke and Yorck, with a member of the Braunschweig class behind the latter, and a small cruiser beyond. To the right are the Helgolands and Nassaus, with Braunschweigs and Deutschlands behind them. (NHHC NH 45199)

Wittelsbach, as rigged at the outbreak of war. She and her sisters were mobilised in August 1914 as the main element of the IV. Sqn. (Author’s collection)

Ships were brought up to current rigging standards, where this had not been done previously, with spotting positions and aerial spreaders at the junction of their top- and topgallant masts, but little else was done, especially as regards the V. and VI. Sqns, which were withdrawn from active service during the first months of 1915. Of the V. Sqn ships, Kaiser Friedrich III and Kaiser Wilhelm der Große were then laid up at Kiel and Kaiser Barbarossa became a mobile target for the Flensburg torpedo school, while Kaiser Karl der Große became an engineering training ship. Brandenburg and Wörth were being employed as harbour defence floating batteries at the now-occupied Baltic port of Libau (Liepaja; see below), moored just behind its northern and western breakwaters, and thus retained the potential for action longer than their younger squadron-mates.

One of the short-lived VI. Sqn at sea in 1915, along with a V1 type torpedo boat. (NHHC NH 92630)

Kaiser Wilhelm II took up duty in April as the harbour headquarters ship for the High Seas Fleet, and as such remained in commission until 1920. However, all the other Kaiser Friedrich IIIs paid off in November 1915, the V. Sqn being dissolved in January 1916, its residual assets being placed under the authority of Scouting Forces Baltic. The two Brandenburgs remained in commission at Libau slightly longer, but they were withdrawn to Danzig to pay off in December 1915 (Brandenburg) and March 1916 (Wörth). All former ships of the squadron were disarmed during 1916, some later also having their side armour removed, and employed in a range of harbour-service roles for the remainder of the war (see p 139).

The Siegfrieds/Odins were also employed in a number of roles after being removed from the front line, the VI. Sqn being disestablished at the end of August 1915, and nearly all of the ships paid off between September and March 1916 Only Beowulf remained in commission, initially as guard-ship in the Ems, and later as the command ship for Baltic minesweepers (see pp.133–4, below). Like the ships of the V. Sqn and other battleships and large cruisers paid off during the war, the guns of all VI. Sqn ships – except Beowulf and Heimdall – were removed soon after decommissioning for land use (cf. p 129).

Likewise, the V. SG’s operational career was very short: Freya was damaged in a collision on 11 August and became a stokers’ training ship on completion of repairs in September, being reassigned in April 1915 to train boys and cadets, with a reduced armament. Victoria Louise was paid off at the end of October and was disarmed during the first week of November, becoming a mine- and accommodation hulk at Danzig. The same month, Hertha was reduced to an accommodation ship for the Naval Air Station at Flensburg, Vineta took on a similar role for submarine personnel, and Hansa did so at Kiel Dockyard. However, the IV. Sqn and the III. SG remained active in the North and Baltic Seas until the autumn of 1915 (see below).

THE NORTH SEA 19142

A key objective of the High Seas Fleet commander, Gustav von Ingenohl (1857-1933) was to reduce the strength of the Grand Fleet to such a degree that a subsequent fleet action would have the prospect of German success. Before the war, it had been anticipated that a close blockade strategy would be pursued by the Grand Fleet, leaving it open to decimation by mine and torpedo. However, in the event the British, recognising the impracticability of the time-hallowed close blockade, adopted the alternate strategy of distant blockade – effectively stopping the exits of the North Sea to prevent commerce passing through. Accordingly, other approaches were required to carry through a reduction in Grand Fleet strength. Apart from wider-ranging minelaying and submarine activity, it was decided to carry out surface operations of sufficient size to draw out a part – but not all – of the British battlefleet, which would then be surprised and obliterated by the lurking High Seas Fleet. The ‘bait’ for such operations would be the large cruisers of the I. SG.

The North Sea, showing locations significant to German capital ships 1871-1918, in particular actions of the First World War. (Author’s map)

The Yarmouth Raid

The first such operation began on 2 November 1914, when the I. SG, comprising Seydlitz (flag), Von der Tann, Moltke and Blücher, supported by the II. SG’s small cruisers Straßburg, Graudenz, Kolberg and Stralsund, sailed to bombard the coastal town of Yarmouth, and lay mines between there and Lowestoft. Two squadrons of battleships and supporting vessels sailed some time later to provide the ‘ambush’ force.

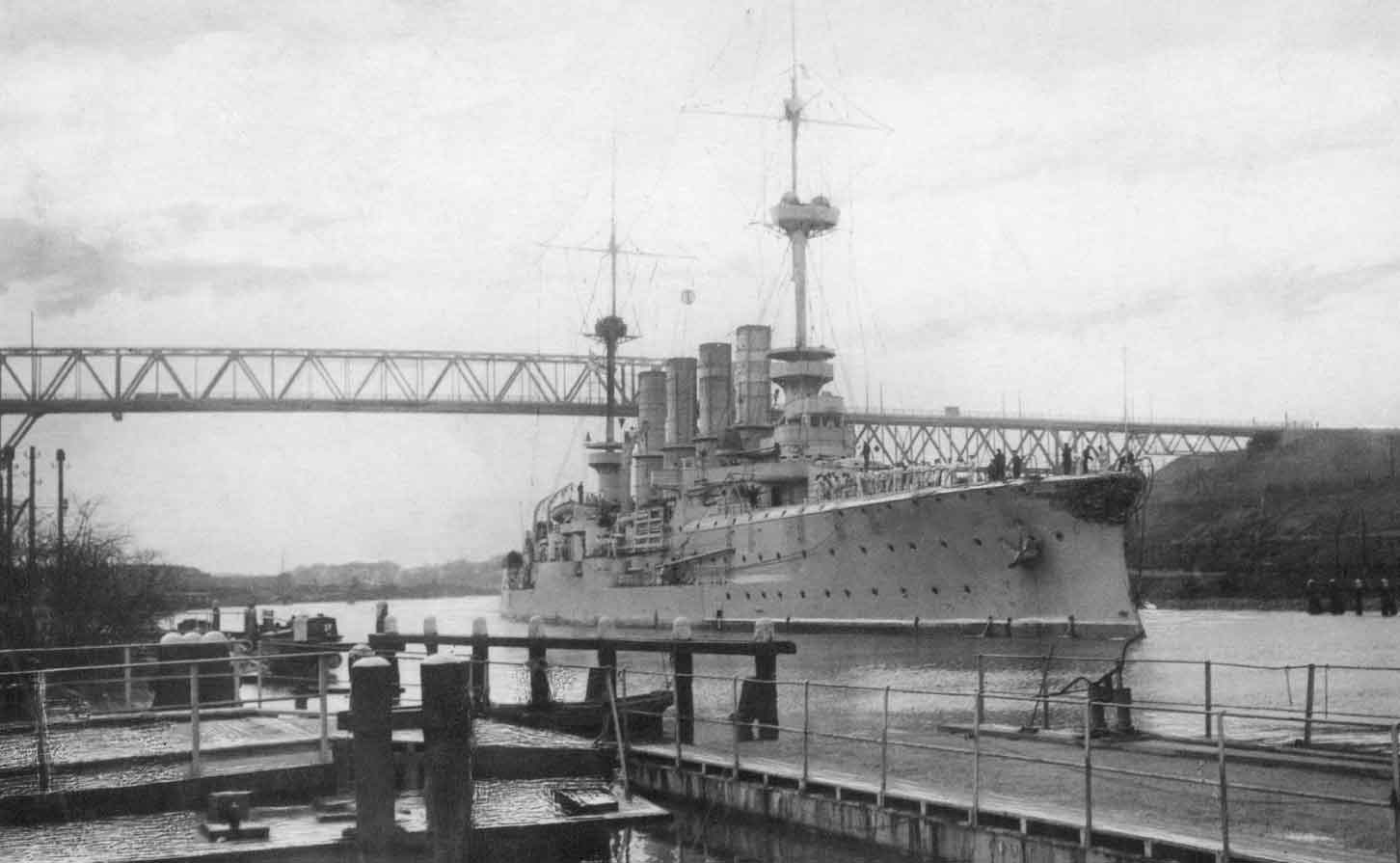

An early loss was Yorck, sunk on a friendly minefield on 4 November 1914 while returning from covering the Yarmouth raid. She is seen here before the about to exit the Kiel Canal through the locks at Holtenau, with the Prinz Heinrich Bridge in the background. Note the double searchlights in the foretop, added as part of the fleet-wide searchlight modification programme up to 1910. (Author’s collection)

In the event, the next morning the raiding force did no more than land a few shells on the beach (which were armour-piercing, high-explosive ones not then being available) and skirmish with British light forces, a force of British battlecruisers being ordered towards the action long after the raiders had begun to withdraw. The only direct losses were HMS/M D5, sunk by a mine laid by Stralsund, and three British trawlers. However, Yorck, serving with the covering force, strayed into a German defensive minefield at the mouth of the Jade on the morning of 4 November, having missed the swept channel in fog while attempting to reach Wilhelmshaven ahead of the rest of the fleet to rectify defects; she sank with the loss of 336 men.

The Hartlepool, Scarborough and Whitby Raid

A further operation of the this type was to be carried out by the same group of cruisers, augmented by the brand-new Derfflinger, together with eighteen torpedo boats, against three further coastal towns on 16 December. All three squadrons of battleships of the High Seas Fleet were deployed in support 130nm to the east (the III. Sqn being only five strong, as the brand-new König was under repair and Markgraf and Kronprinz had still to complete their trials), together with the two surviving ships of the III. SG, the seven ships of the IV. SG and fifty-four torpedo boats. Submarines were placed off Harwich and the Humber to attack any British ships reacting from these ports.

The departure of the cruisers on 15 December was detected by British code-breakers3 – but not that of the battlefleet. Thus, the response was to dispatch just the BCS (Lion, Queen Mary, Tiger and New Zealand – the remaining four British battlecruisers were overseas), the 2nd BS (King George V, Ajax, Centurion, Orion, Monarch and Conqueror), the 1st LCS (Southampton, Birmingham, Falmouth and Nottingham) and destroyers from the Grand Fleet, plus the light cruisers Aurora and Undaunted and forty-two destroyers from Harwich and the armoured cruisers of the 3rd Cruiser Sqn (Devonshire, Antrim, Argyll and Roxburgh) from Rosyth. This assemblage was placed to intercept the German raiding force on its return voyage.

Bad weather meant that all the small cruisers except Kolberg (carrying mines) and torpedo boats were detached from the raiding force to return home early on the morning of the 16th. Seydlitz, Blücher and Moltke were to bombard Hartlepool, while Derfflinger, Von der Tann and Kolberg were to attack Scarborough and Whitby. Hartlepool was defended by 6in [152mm]-armed shore batteries, a pair of light cruisers and destroyers, the batteries scoring four hits on Blücher, one on the forward superstructure disabling two 8.8cm guns and killing nine. The second hit was on a starboard 21cm turret, wrecking its sight and rangefinder, but leaving it still operational, the third shell striking the belt below. The fourth hit the foremast, damaging aerials and other equipment. Seydlitz received three hits, one on the forecastle, one which passed through the casing of the fore funnel, making a 4 to 5 metre-square hole in the uptake itself, and one on the aft superstructure, splinters from which penetrated the low-pressure turbine room; however, there were no casualties. Moltke received a single hit, forward.

Of the four British destroyers patrolling in the area, Doon, Test, Waveney and Moy, only the first-named was able to attack the German force, firing three torpedoes, all of which missed, the destroyer retiring damaged. Neither British cruiser was able to come into action, Patrol ran aground after two hits from Blücher, while Forward was only able to leave harbour when the Germans had already begun their retirement.

The bombardment of Hartlepool, during which some 1150 German shells were expended, killing seven soldiers and eighty-six civilians, with fourteen soldiers and 424 civilians injured. Three hundred houses were damaged and significant damage caused to industrial and other infrastructure. At Scarborough, no effective defences were available, significant damage being caused by the cruisers’ secondary and tertiary batteries, 333 15cm and 443 8.8cm shells being expended. Von der Tann and Derfflinger then sailed for Whitby to destroy the signal station there, firing 106 15cm and 82 8.8cm shells. Their tasks finished, the ships then sailed for their rendezvous point, beginning the homeward journey around 11.00.

Meanwhile, at 05.15, the screens of the British force and the High Seas Fleet had come into contact. Roon which, with Prinz Heinrich, was in the van of the High Seas Fleet, ran into Lynx and Unity, but no shots were exchanged. Unfortunately for the Germans, concerns at exceeding standing orders regarding avoiding action with potentially superior forces meant that it was decided at this point to withdraw the High Seas Fleet – only a few minutes away from encountering just the kind of detached element of the Grand Fleet that the strategy had envisaged as the fleet’s victim. The likely outcome of an engagement between the British squadrons and the much larger High Seas Fleet has been much debated. The British had superior speed (in particular given the speed-handicap of the II. Sqn) and could have fairly easily withdrawn, but it is possible that they could have decided to stand and fight: given the issues regarding British shells and damage-resistance that became apparent at Jutland, a negative outcome for the British would have not been unlikely.

The reversal of the fleet’s course placed Roon at the tail of the line, and at 05.59, the large cruiser, now joined by the small cruisers Stuttgart and Hamburg, again encountered British destroyers, which shadowed her until 06.40, at which point the two small cruisers were detached to deal with them. However, they were recalled at 07.02, and the ships continued home in the wake of the fleet. News of the encounter reached the BCS at 07.55, and New Zealand was directed towards the location of the action, followed by the remainder of the squadron. The pursuit was, however, broken off when news of the Scarborough bombardment diverted the British to attempt to deal with the I. SG.

The remainder of the Grand Fleet then sailed to join the hunt, and during the middle of the day there were a number of encounters between the British and German forces, but various breakdowns in communication within the British forces meant that no action was joined, and the I. SG reached port safely. During the High Seas Fleet’s retreat, HMS/M E11 fired a torpedo at Posen, which missed and all of the fleet returned safety.

THE PACIFIC 1914

It had long been realised that the base of the East Asiatic Squadron, Tsingtau, would be untenable in the event of general war and thus that the cruisers should ensure that were not blockaded there. The news of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand came while Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were in the German Caroline Islands, arriving at Ponape on 17 July, where they were still at the beginning of August. The small cruisers of the squadron, which had been in various parts of the Pacific, were recalled, the large cruisers, plus the small cruisers Nürnberg and Emden, the auxiliary cruiser Prinz Eitel Friedrich and colliers concentrating at Pagan in the Marianas on 11 August.

Emden and Prinz Eitel Friedrich were detached to act as commerce-raiders on 13 August, the remaining ships heading for Enewetak Atoll in the Marshall Islands, arriving and coaling on 20 August. On 8 September Nürnberg was sent to Honolulu with dispatches and to gather news, the squadron then sailing to the recently-captured German Samoa in the hope of catching an isolated British warship. However, nothing was found there on the 14th, although better luck was had at the French harbour of Papeete, on Tahiti, on 22 September, where the gunboat Zélée was sunk and the town bombarded by Scharnhorst and Gneisenau.

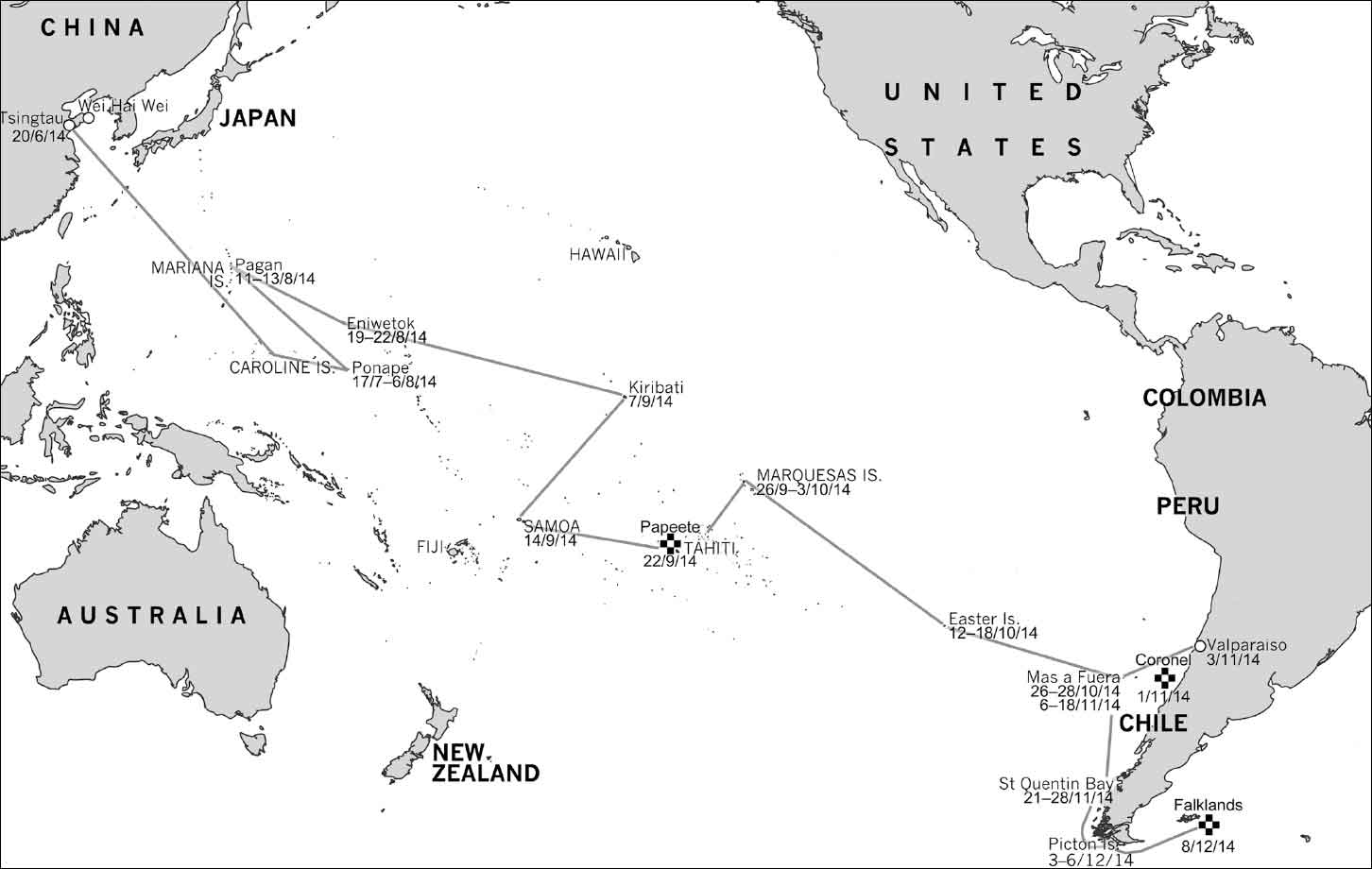

The Pacific, showing the track of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau between June and December 1914. (Author’s map)

On 12 October, the German ships reached Easter Island, where they were joined from American waters by Dresden and Leipzig, together three more colliers. A week later, the squadron pushed on to Mas a Fuera, and then towards and down the Chilean coast, seeking the British light cruiser Glasgow, which was known to be in the area.

The Battle of Coronel

At 16.20 on 1 November, the squadron encountered not just Glasgow, but also the armoured cruisers Good Hope (flag) and Monmouth, together with the armed merchant cruiser Otranto. Apart from a pair of 9.2in [234mm] in Good Hope – in any case outranged by over 2000m by the German 21cm weapons – the British ships’ biggest guns were of 6in calibre, half mounted in main-deck casemates that were unworkable in the heavy seas then running; they were thus massively outgunned by the two German large cruisers, leaving aside the presence of the two German small cruisers. In addition, apart from Glasgow, the British ships had all commissioned from Reserve on mobilisation a few months earlier, and thus were at a further disadvantage to the fully worked-up and experienced German crews. While the setting of the sun behind the British ships gave them an initial tactical advantage, the Germans declined action until sunset, after which they were silhouetted against the horizon, with the German ships lost in the gloom.

When fire was opened around 19.00, Scharnhorst engaged Good Hope, her third salvo putting the British cruiser’s forward 9.2in out of action, followed by a series of hits to forward part of the ship – including the bridge – with more shells amidships setting Good Hope on fire. The aft turret having been hit twice, there was a large explosion at 19.50 between the after funnel and the mainmast, leaving the ship dead in the water. Visual contact was lost ten minutes later – which was probably when Good Hope sank with all hands.

Monmouth was taken on by Gneisenau: completely outranged, the British ship was unable to respond as her fore turret was demolished and the forecastle set on fire by an early salvo. Having been hit by some thirty to forty shells and on fire aft as well, Monmouth attempted to steam away to the west, but was found around 21.00 by Nürnberg, down by the head and with a list to port. She was then sunk with all hands, leaving only Glasgow, which had been engaged by Leipzig and Dresden but had escaped with five hits. Scharnhorst had received two 6in hits and Gneisenau four, none of which had done significant damage, but both ships had now expended nearly half their ammunition outfits. Following the battle, the German squadron proceeded to the Chilean port of Valparaiso, neutrality rules allowing only three ships to enter port at the same time, for a maximum of 24 hours. Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Nürnberg came in on 3 November to coal, sailing the next morning for Mas a Fuera, arriving on the 6th, and more coaling. On the 15th, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Nürnberg sailed for St Quentin Bay in the Gulf of Penas, on the south-east coast of Chile, being joined en route by Dresden and Leipzig, which had travelled via Valparaiso, arriving on the 21st. There, they prepared to break back to Germany across the Atlantic.

The Battle of the Falklands

The German squadron departed St Quentin Bay on 26 November, rounding Cape Horn on 2 December, stopping at Picton Island, at the very tip of South America on the 3rd. While there, it was agreed to undertake a raid on the Falkland Islands before pushing on homeward, the squadron sailing on the 6th.

In the interim, two battlecruisers (Invincible [flag] and Inflexible) had been dispatched from Great Britain to hunt down the German ships and, as Gneisenau and Nürnberg approached the Falklands on the 8th, had been in harbour there since the previous day, together with the armoured cruisers Kent and Carnarvon, plus the Coronel-survivor, Glasgow and the battleship Canopus, grounded as a floating battery. A 12in [305mm] hit from the latter on Gneisenau dissuaded the Germans from pressing home what might have been a successful assault on the British force while it was confined in harbour, the German force instead steaming away, initially unaware of the presence of the 25kt battlecruisers that could outpace the German ships’ best speed of 22kt.

Within three hours, Invincible and Inflexible had sailed and caught up with the Germans, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau accepting action at 13.20 in the hope that the small cruisers might escape. However, while the big ships were exchanging fire, most of the British smaller cruisers were being directed to chase their German opposite numbers. The flagships engaged each other, Scharnhorst straddling Invincible with her third salvo, scoring two hits without damage to herself, the two German vessels managing to close the range to allow their 15cm batteries to take part, causing the British to fall back. However, soon afterwards Scharnhorst received a number of hits and caught fire, although continuing to score hits on Invincible. A British manoeuvre then led to the ships swapping opponents, Inflexible now hitting Scharnhorst, which was now listing and had lost her third funnel, previously damaged at Coronel.

Gneisenau had also been badly battered in her dual with Inflexible, with her secondary battery largely wrecked, the forward boiler room flooded and another leaking badly. Around 16.00 she was briefly hidden by smoke, leading to both battlecruisers concentrating on Scharnhorst, now a wreck and down by the bow: she capsized to port and sank with all hands at 16.17. Ordered to try and escape, Gneisenau, now capable of only 16kt, was now under fire from not only the battlecruisers, but also Carnarvon, but continued to fight, hitting Invincible for a final time at 17.15. However, with her forefunnel wrecked, her foremast badly damaged, and listing heavily, Gneisenau stopped at 17.40. She sank before 18.00, with her seacocks open; there were 190 survivors.

Scharnhorst at Valparaiso after the battle of Coronel on 3 November 1914; Gneisenau is visible in the background. (BA 134-C0001)

Of the small cruisers, Nürnberg was sunk by Kent, while Leipzig succumbed to Kent and Glasgow. Only Dresden escaped, to be scuttled at Mas a Tierra, off the Chilean coast, when cornered by the armed merchant cruiser Orama, together with Kent and Glasgow, the latter thus completing her revenging of her Coronel squadron-mates.

THE MEDITERRANEAN AND BLACK SEA 1914–1915

Had war not broken out, the intention had been that the original ships of the Mediterranean Division, now in need of refit, should have been relieved in the summer of 1914, with Goeben to be replaced by her sister Moltke. However, with the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in June, this exchange was suspended and the division proceeded to Pola for repairs, including Goeben having 4460 of her boiler tubes replaced. Sailing on 23 July and coaling at Trieste, the German ships arrived at Messina on 2 August, where they once again coaled while the world fell into war.

In the event of conflict, the division had been envisaged as disrupting the movement of French troops from the North African colonies, and/or breaking out through the straits of Gibraltar and returning to Germany. On 3 August, following the outbreak of war with France, Goeben undertook a short secondary-battery bombardment of Philippeville (Skikda, Algeria), while Breslau shelled Bone (Annaba).

Orders were then received (contrary to standing instructions) to sail to Constantinople, a journey that could not be undertaken without coaling, which was planned to take place once again at Messina. En route, at 10.15 on the 4th, the German ships encountered the British battlecruisers Indefatigable and Indomitable, but as Great Britain had not yet declared war, no hostile moves were made, although Goeben and Breslau were now shadowed by the British ships – which had, however, been eluded by the time that the Germans reached Messina on the 5th.

Although Italy had declared her neutrality on the 2nd, with the result that belligerent warships were only allowed to remain in port for twenty-four hours, sympathetic Italian officials – Italy had hitherto been part of the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary – permitted the German cruisers to remain for an extra half-day while receiving coal from a German collier. However, they still did not have enough coal to get them to Turkish waters, whence they were once again directed, after a brief consideration of diverting them to the Adriatic or the Atlantic. Goeben and Breslau left on the 6th, and were shadowed for a while by the light cruiser Gloucester which was, however, soon shaken off.

The idea that Goeben and Breslau might head for Turkey was not easily grasped by the Anglo-French commanders, the French fleet remaining in the western Mediterranean on the assumption that the German ships would either attempt to break out into the Atlantic, or join the Austro-Hungarian forces in the Adriatic. The three British battlecruisers in the Mediterranean (the third was Inflexible) were also far away when the German force sailed from Messina, aiming to find a secluded spot in the Aegean to take on further coal. On the other hand, the British 1st CS (armoured cruisers Defence, Black Prince, Duke of Edinburgh and Warrior) was in the vicinity but, misled by the Germans’ initial course, first sought to intercept the German ships at the mouth of the Adriatic.

The error having been realised, the British light cruiser Dublin and two destroyers were ordered to make a torpedo attack, but failed to make contact in the dark. The armoured cruisers continued the chase until early on the 7th, when the British admiral (Sir Ernest Troubridge [1862–1926]) concluded that Goeben represented too superior a force to risk the British ships and withdrew – a decision that earned him a court martial (at which he was acquitted). Thus, having coaled off the Greek island of Donoussa in the Cyclades on 9/10 August, on the afternoon of 10 August Goeben and Breslau were able to enter the Dardanelles unmolested.

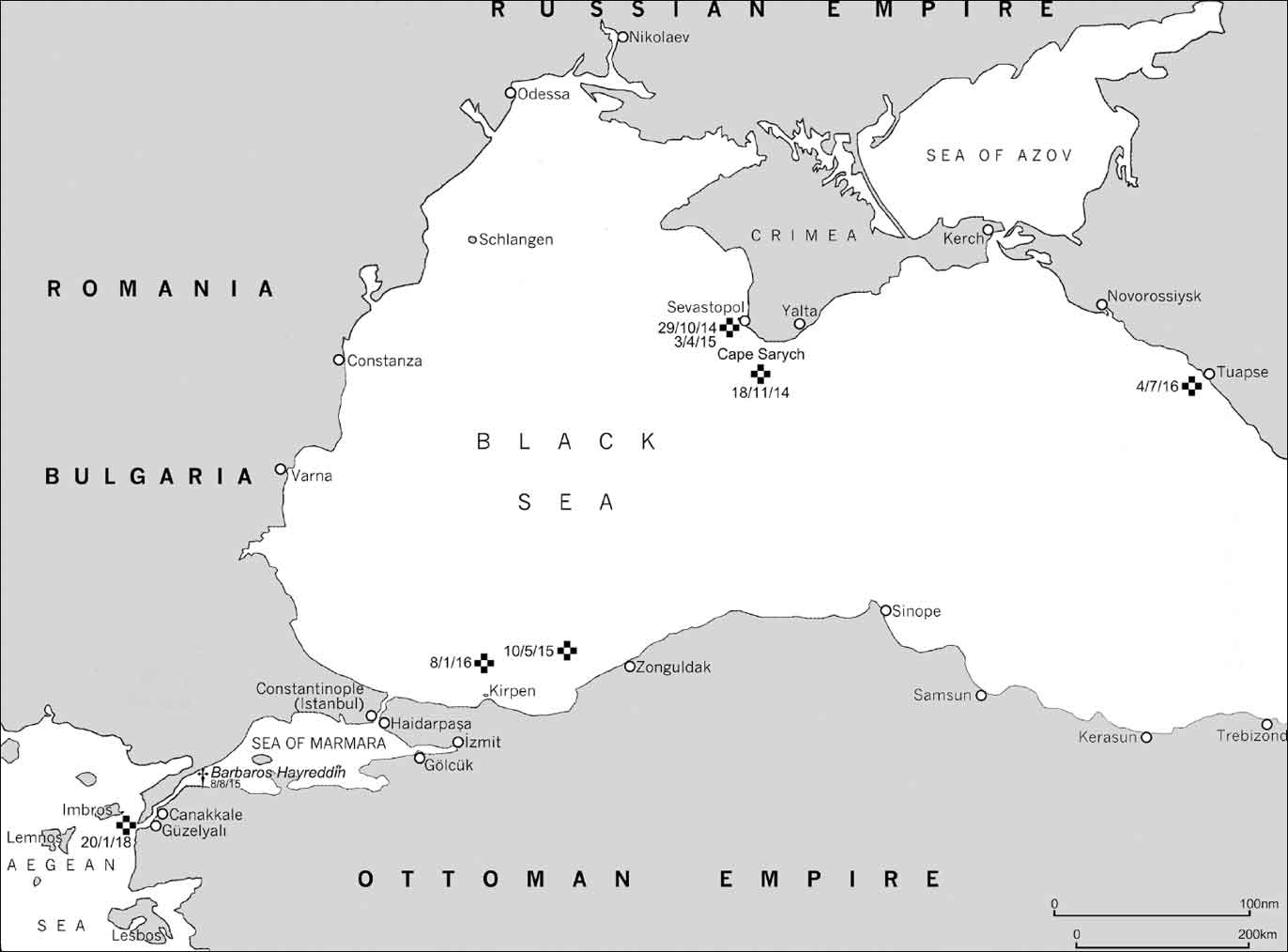

The eastern Aegean and BlackSea, showing principal actions involving Turco-German capital ships between 1914 and 1918; for the Mediterranean and western Aegean, see p 129. (Author’s map)

Goeben soon after hoisting the Turkish flag as Yavuz Sultan Selim: her nameboard still bears her German name. (Author’s collection)

On 16 August, they were ‘sold’ to the Ottoman Navy, Goeben becoming Yavuz Sultan Selim and Breslau becoming Midilli, but retaining their German crews, albeit now dressed in Ottoman uniform. A month later, the British Naval Mission to Turkey returned home, and following day the former German Flag Officer Mediterranean Division became CinC of the Ottoman Navy.

On 21 September, Goeben/Yavuz undertook her first operation under the Turkish flag, a short cruise into the Sea of Marmora, in company with the Turkish destroyers Tasoz and Basra, but 1–10 October were spent completing Goeben/Yavuz’s boiler overhaul, which was finally finished from 18–24th, a short training cruise into the Black Sea having taken place in the interim. Her first offensive operation was then carried out on the 29th when, escorted by Tasoz and her sister Samsun, Goeben/Yavuz carried out a preemptive bombardment of the batteries protecting Sevastopol (war had not yet been declared with Russia), retiring after receiving three large-calibre hits around the after funnel, a boiler being damaged by splinters, as was the starboard crane and a searchlight. On the way back, she encountered the Russian destroyers Leytenant Puschkin, Zharkiy and Zhivuchiy, together with the minelayer Prut. The latter was scuttled to avoid capture, but the destroyers managed to escape, although Puschkin was damaged by 15cm fire from Goeben/Yavuz. A small merchantman, Ida, was also captured on the return voyage. Breslau/Midilli and various other Turkish vessels took part in other operations the same day against Russian ports, which led to Russia declaring war on the Ottoman Empire on 2 November, followed by Great Britain and France on the 5th.

The 6th saw Goeben/Yavuz and the torpedo cruiser Berk-i Satvet sortie for an abortive bombardment of Sevastopol, while she was again at sea from 9th to 12th to cover an abortive troop convoy, and once more on the 14th in company with Breslau/Midilli in response to a Russian submarine’s bombardment of Trebizond. This led on 18 November to the battle of Cape Sarych with the Russian Black Sea Fleet battle brigade (Evstafii, Ioann Zlatoust, Panteleimon, Tri Sviatitelia and Rostislav), which was returning from a bombardment of the same port. The first 12in [305mm] salvo from Evstafii hit Goeben/Yavuz in P3 15cm casemate, causing an ammunition fire that killed thirteen. In response, Evstafii was hit on her middle funnel, severing her radio antenna, with consequences for the squadron’s fire control, and then three times more, and suffering thirty-three fatalities, before action was broken off.

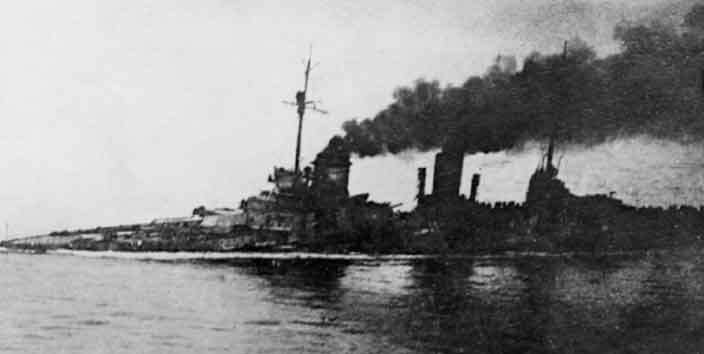

Units of the expanded Turkish fleet sortie: from the left the light cruiser Midilli (ex-Breslau), the destroyer Basra and the battleships Turgut Reis and Barbaros Hayreddin. (BA 183-36430)

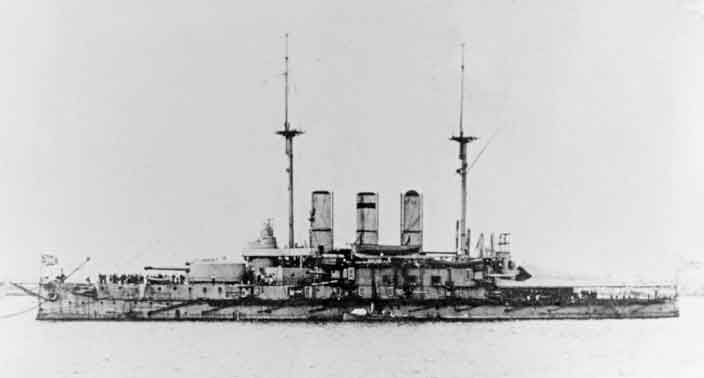

The Russian battleship Ioann Zlatoust, an opponent on more than one occasion of Goeben/Yavuz. (NHHC NH 84828)

The two Turco-German cruisers, together with the torpedo cruisers Peyk-i Sevket and Berk-i Satvet covered a troop convoy during 5–6 December, while Goeben/Yavuz bombarded Batum on the 10th, before rendezvousing with the cruisers Mecidiye and Berk-i Satvet. She provided further coverage for Turkish troop ships on the 21st (together with the cruiser Hamidieh) before rejoining Breslau/Midilli to patrol off the Antalolian coast to guard against any Russian raids over Christmas. Returning to Constantinople on the 26th, Goeben/Yavuz struck two mines 1nm from the Bosphorus. The first, below the conning tower on starboard side, blew a 50m2 hole in the hull, the second, on the port side just forward of the wing barbette, opened-up a 64m2 hole, but in both cases the torpedo bulkhead held, although bowed on the port side, flooding being restricted to some 600t of water.

The war situation did not allow immediate repairs (which would require the construction of cofferdams, there being no dry dock big enough to take the large cruiser in Turkish waters), Goeben/Yavuz sortieing twice, on 28 January and 7 February to cover the returns of the Breslau/Midilli and Hamidieh after action with Russian forces. She was finally released for repair on 9 February, the port side cofferdam being put in place on the 23rd, allowing repairs to be completed.

In March, the British and French launched the Dardanelles Campaign. The sea battle was essentially between the Anglo-French bombardment fleet and Turkish shore batteries, supported by light craft and submarines, but on 6 March, Barbaros Hayreddin exchanged fire with the brand new 15in [380mm]-gunned battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth, scoring three hits on the British vessel with her 28cm guns, all striking the belt below water, with little damage. She and her sister had been brought forward from initial roles as floating batteries, and on 25 April they attempted to interdict the first day of British landings. However, after firing fourteen rounds, Barbaros Hayreddin suffered a premature detonation in the right gun of the centre turret, wrecking the gun.

Goeben/Yavuz returned to service on 1 April, sailing with Breslau/Midilli to take part in an operation off Sevastopol, but after Mecidiye was mined and sunk during a parallel operation against Odessa, they joined with the survivors of that operation to return home on the 4th. En route back, Goeben/Yavuz sank two Russian merchantmen, and exchanged fire with the Russian cruiser Pamiyet Merkuria, before having her starboard-side cofferdam fitted the next day; patching work was finished on 1 May. The two old Brandenburgs remained on station in the Dardanelles until early June, when they were withdrawn following an accidental explosion in one of Turgut Reis’s turrets.

On 10 May, while return on a sortie towards Sevastopol, Goeben/Yavuz engaged the Russian battleships Evstafii, Panteleimon and Tri Sviatitelia west of Zonguldak, being hit on the forecastle by Panteleimon, the shell penetrating the main deck and exploding below, and also on the starboard waterline, abreast the forefunnel. S2 15cm mounting was damaged and a number of leaks caused; Goeben/Yavuz retired without damaging the enemy. While under repair, two 15cm guns (P4 and S4) and the four 8.8cm guns (from the after superstructure) were removed for use ashore, the latter being replaced by anti-aircraft guns of the same calibre before the end of year.

After their withdrawal from combat, the two Brandenburgs acted as ammunition transports in the war zone, Barbaros Hayreddin being so employed when torpedoed and sunk by HMS/M E11 on 8 August while en route to Suvla Bay; hit in the forward boiler room, she capsized in seven minutes, with the loss of twenty-one officers and 347 men. Two days later, Goeben/Yavuz was, with Hamidieh and three torpedo boats, escort to a coal convoy from Zonguldak to the Bosphorus. One of the colliers was sunk by the Russian submarine Tyulen, which also attempted to attack Goeben/Yavuz the following day. The ship continued to cover these coal convoys until 14 November, when she was narrowly missed by the Russian submarine Morzh, after which the view was taken that the danger to the ship was too great to allow her to continue to do so.

THE NORTH SEA 1915

The Battle of Dogger Bank

The I. SG’s follow-on operation to the Hartlepool, Scarborough and Whitby raid was intended to probe the Dogger Bank and attack the fishing fleet there that was suspected of being a key source of British intelligence on German movements: that German naval codes had been compromised was as yet unsuspected. No High Seas Fleet support was available – the III. Sqn was absent in the Baltic – while the I. SG was short of Von der Tann, rectifying defects. The raiders were to be accompanied by Kolberg, Stralsund, Rostock and Graudenz and eighteen torpedo boats.

The British were aware of the operation five hours before the German force sailed on 23 January 1915. Following the raids in 1914, the British battlecruisers had been moved from Scapa Flow to Rosyth, as had been the 3rd BS (six King Edward VII class), joining the 3rd CS already there. The latter two formations were deployed to guard against a German move northwards, while the Battle Cruiser Force (1st BCS: Lion, Tiger and Princess Royal; 2nd BCS: New Zealand and Indomitable; 1st LCS: Southampton, Birmingham, Lowestoft and Nottingham) and Harwich Force (Aurora, Arethusa, Undaunted and thirty-five destroyers) were directed to intercept. The remainder of the Grand Fleet also sailed as a back-stop to the south.

British and German light cruisers met at 07.05 on the 24th, with the engagement between the British battlecruisers and the German force beginning at 08.52. During the first hour, Seydlitz and Derfflinger each received two hits, Blücher one and Lion two. All did little damage, except for one on Seylitz that passed through the upper deck and entered the aft barbette, flash penetrating the working chamber and igniting the propellant charges inside. The fire spread up into the turret and downward towards the magazines, an explosion only being prevented by their immediate flooding. However, the crew of the turret attempted to escape into the adjacent mounting, meaning that both turrets were burned out, with the loss of their entire crews – 159 men.

During the next 45 minutes, Seydlitz received a further hit – with little effect – but Lion was hit by four shells, three causing significant machinery damage. At 10.30, Blücher received a hit that penetrated her fore-aft ammunition passage, thirty-five to forty cartridges catching fire, which spread a forward wing turret; the uptakes from the forward boiler room were also damaged, cutting the ship’s speed to 17kt, causing her to fall behind her companions. Soon afterwards Lion received a series of further hits that damaged her port engine and knocked her out of the battle. A signalling error then resulted in the remaining British ships turning to attack Blücher, rather than chase the rest of the German force, which was able to escape. Blücher was then overwhelmed, being hit fifty to a hundred times by heavy shells, but only sinking after being hit by two torpedoes fired by Arethusa, having scored final hits on Tiger, Indomitable and the destroyer Meteor. Seven hundred and ninety-two men lost their lives, 260 being rescued by British destroyers. Seydlitz was under repair at Wilhelmshaven from 25 January to 31 March.

Blücher capsizing at the battle of Dogger Bank. (Author’s collection)

After Dogger Bank

Dogger Bank was regarded, with the Hartlepool, Scarborough and Whitby operation and the destruction of three small cruisers by British battlecruisers at the First Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28 August 1914, as illustrating of the failure of von Ingenohl’s strategy. He was therefore replaced on 2 February by Hugo von Pohl (1855–1916), formerly Chief of the Naval Staff.

A number of short sorties were carried out, on 29/30 March and 29/30 May to the north of Terschelling, on 17/18 April and 17/18 May to cover II. SG mining operations, on 21/22 April towards the Dogger Bank, on 10 May to cover the return of the auxiliary minelayer Meteor (which had, however, been sunk the previous day), on 11/12 September to cover a minelaying operation west of Terschelling, and on 23/24 October as far as the Horns Reef. In no case was there any potential contact with British forces. The III. SG was withdrawn from High Seas Fleet 12 April 1915, the ships providing reinforcement for operations in the Baltic.

THE BALTIC 1914–1915

On 28 August 1914, the IV. Sqn made a foray into the Baltic after the stranding of the small cruiser Magdeburg off the Estonian coast, followed by an offensive sweep during 3–9 September, led by Blücher, detached from the I. SG (as flag), with the small cruisers Augsburg, Gazelle, Amazone and Straßburg. This succeeded in sinking a Russian merchantman and destroying some shore stations, with the flagship briefly exchanging fire with the Russian armoured cruisers Bayan and Pallada at the entrance to the Gulf of Finland on the 4th. Blücher and Straßburg returned to the North Sea on the force’s return to Kiel, while the IV. Sqn was also detached from the Baltic command, but remained at Kiel.

Otherwise, the navy undertook bombardment operations in support of the army advance, the small cruiser Augsburg bombarding Libau on the Latvian coast as early as 2 August. A bombardment for 17 November, however, was accompanied by disaster, when Friedrich Carl struck a mine in a field laid by Russian destroyers west-south-west of Memel on the 5th. Assuming that she had been torpedoed, the ship set a course for shallow water that took her back into the minefield, where she struck a further mine, causing extensive flooding aft and disabling an engine. The rudder jammed soon afterwards, Friedrich Carl’s crew being taken off by Augsburg some six hours after the first mine had been struck, and shortly before the big ship capsized and sank, albeit with only seven fatalities. Friedrich Carl was replaced as Baltic flagship by her sister Prinz Adalbert, withdrawn from the III. SG in the North Sea.

The mine danger was emphasised when Augsburg and Gazelle were damaged in two separate minefields near the Danish island of Bornholm on the night of the 24/25 January 1915. A further submarine threat had arisen in October 1914, with the first deployment of British submarines to the Baltic; as noted below, mines and torpedoes would ultimately make much of the eastern Baltic untenable for German surface vessels. The mine danger led on 24 January to Prinz Adalbert taking a course towards Libau that took her through shallow waters in which she ran aground, fortunately being refloated before HMS/M E9 reached her position.

Nevertheless, the heavy naval forces available in the Baltic theatre were enhanced in April 1915 when the remaining ships of the III. SG (Roon and Prinz Heinrich) were redeployed there. Also, on 6 May, the IV. Sqn provided support for the German land-based assault on Libau, the ships being stationed off Gotland to intercept any Russian vessels that might attempt to intervene. On 10 May, the squadron was spotted by the British submarines E1 and E9, but they were unable to get into an attacking position. During these operations, the squadron’s Wittelsbachs erected a dummy third funnel give the squadron the appearance of being composed entirely of Braunschweigs. On 11 May, E9 sighted Roon and several other ships en route to Libau; five torpedoes were fired, but all missed.

The Baltic, showing the location of principal actions involving German capital ships between 1914 and 1918. (Author’s map)

On 2 July, Augsburg and three destroyers, escorting the cruiser-minelayer Albatross, were attacked by the Russian cruisers Bayan, Admiral Makarov, Bogatyr and Oleg. Augsburg successfully withdrew, while the destroyers attempted to cover Albatross, which was forced by heavy damage to seek refuge in neutral Swedish waters, where she ran aground and was later interned. Roon and the small cruiser Lübeck sailed to support the destroyers, and on arrival Roon engaged Bayan, while Lübeck opened fire on Oleg. The Russians were soon reinforced by the big armoured cruiser Rurik and the destroyer Novik, and the German ships were forced to withdraw. The other two ships of the III. SG, Prinz Heinrich and Prinz Adalbert, were sent from Danzig to provide further support, but the latter ship was torpedoed below the conning tower by HMS/M E9 en route. Prinz Adalbert lost ten men and was flooded by some 2000t of water, increasing her draught beyond that which would allow her to re-enter Danzig. She was, however, able to proceed under her own power to Kiel for repairs, arriving on 4 July.

From 7 July, the IV. Sqn was active in support of the army advance towards the Gulf of Riga, during which, in the absence of Prinz Adalbert, Braunschweig and Elsaß joined Roon and Prinz Heinrich in the scouting force. The following month, August, a major operation was carried out against Russian forces in the Gulf of Riga, when the older ships hitherto employed in the Baltic were joined by the I. Sqn and Moltke, Von der Tann and Seydlitz in an attempt to destroy local Russian forces. Particular objectives were to neutralise the battleship Slava and mine the entrance to the Moon Sound channel, the northern entrance to the gulf.

Prinz Adalbert down by the head after being torpedoed in the Baltic on 2 July 1915. (BA 134-B2185)

On 8 August, minesweepers attempted to clear a channel through the Irben Strait, the southern entrance to the gulf, but came under fire from Slava and the gunboats Khrabryi and Groziashchii. Braunschweig and Elsaß then engaged the Russians at a range of some 17 kilometres, the remaining German ships staying to seaward. However the operation was suspended at nightfall, with the minefields not yet breached and the minesweepers (ex-torpedo boats) T52 and T58 mined and sunk. Meanwhile, on the 10th, Roon and Prinz Heinrich had shelled Russian positions at the Sworbe (Sõrve) Peninsula, slightly damaging a Russian destroyer; Von der Tann and the small cruiser Kolberg were detailed to bombard the island of Utö.

On 16/17 August, a second attempt was made to force an entrance into the gulf, spearheaded by Nassau and Posen, accompanied by four small cruisers and torpedo boats. This proved successful, for the loss of the torpedo boat V99 (scuttled after mine and gunfire damage) and the minesweeper (ex-torpedo boat) T46 (mined), the two battleships exchanging fire with Slava at long range on two occasions, the first without effect, but on the second scoring three hits on the Russian battleship. However, the German success was stalled when the HMS/M E1 torpedoed Moltke on the morning of 19 August, flooding the bow torpedo room with 435t of water, with the loss of eight men. The clearly-real threat from submarines and mines (the torpedo boat S31 was sunk that evening), combined with the fact that the Russian batteries on Ösel (Saaremaa) Island, commanding the Irben Strait, were still operational, led to the operation being called off on the 20th. Moltke was repaired by Blohm & Voss between 23 August and 20 September.

From 9 to 11 September, operating from Libau, the newly returned Prinz Adalbert, with Roon, Braunschweig and Elsaß (Prinz Heinrich was at Kiel for boiler repairs) undertook a sweep towards Gotland, a further operation being carried out by Prinz Adalbert, Braunschweig, Elsaß, Schwaben, Mecklenburg, Zähringen and the small cruiser Bremen (Roon was also now away for repairs) on 21–23rd. Prinz Heinrich returned to Libau on 22 September and covered a minelaying operation on 5–6 October, in company with Prinz Adalbert and Bremen.

Roon returned from her repairs on the 18th, but on 23 October Prinz Adalbert was torpedoed by HMS/M E8 off Libau, the explosion detonating a magazine (probably one of the 15cm broadside ones, in which shells were stowed nose-outward), the cruiser breaking in two and sinking with the loss of 672 men. Braunschweig was missed by HMS/M E18 the same month, before the small cruiser Undine was sunk by E19 in November. Mines damaged the small cruiser Danzig the same month, sank Bremen and the torpedo boats V191 and S177 in December, and damaged the small cruisers Lübeck and Gazelle in January 1916. This string of events convinced the German navy that the continued operation of big ships in the area was becoming too dangerous, and in November the Wittelsbachs, along with Prinz Heinrich, returned to Kiel to be placed alongside at reduced readiness until early 1916, when all paid off for disarmament and allocation to subsidiary duties. Braunschweig finally left the theatre in August 1916 for Kiel, where she joined Elsaß; both became training ships with reduced complements (and lower-ranked commanding officers).

Brandenburg serving as a distilling ship at Libau from 1916 to 1918. Her main battery has been removed to provide spares for her Turkish sister. (BA 134-B4087)

A short while before Braunschweig departed, Brandenburg arrived back at Libau, but now under tow and no longer a fighting ship. She had been disarmed at Danzig during December 1915, to provide spare guns for her Turkish sister Turgut Reis, before being refitted as an accommodation and distilling ship for submarines. The former battleship remained at Libau until February 1918, when she was towed back to Danzig with the intention of converting her to a target ship, to replace Oldenburg (i) – work that was never completed.

THE NORTH SEA 1916

The Raid on Lowestoft and Great Yarmouth

Pohl, terminally ill, was replaced by Reinhard Scheer (1863–1928) in February 1916. While the basic concept of picking off elements of the Grand Fleet remained intact, the new CinC wished to be more proactive, and on 6 March the I. SG made a reconnaissance as far as a point half-way between the Dutch coast and East Anglia, with the battle-fleet in support off Terschelling. However, the forces returned to base before any action could be taken by the British.

A repeat of the 1914 coastal raid approach was undertaken on 25 April, nominally as a supporting action for the Easter Rising in Ireland, with the hope of intercepting British forces believed to be at sea in the northern and southern parts of the North Sea. However, the northern group (the main body of the Grand Fleet) had been withdrawn early from a sweep begun on the 22nd following a series of collisions that damaged the battlecruisers Australia and New Zealand, the battleship Neptune and three destroyers, and were actually coaling at Scapa Flow.

The targets of the I. SG were to be the towns of Lowestoft and Great Yarmouth. The Group had now been enlarged by the belated joining of Lützow, which had finally became operational on 20 March. She, together with Seydlitz (flag), Derfflinger, Moltke and Von der Tann, were supported by the four small cruisers of the II. SG, and two torpedo boat flotillas. The full battlefleet was to accompany the bombarding force as far a point west of Terschelling, and remain there in support in case of British action. Unfortunately, Seydlitz was mined on the starboard side at 16.00 on the 24th and had to return home, with a flooded torpedo room, 1400t of water in the hull, eleven dead and speed cut to 15kt. Repairs lasted until 29 May. The Group flag was shifted to Lützow, and course altered to avoid the mine danger.

The British were aware of the sailing of the German fleet, a decrypted signal indicating that an objective was Yarmouth. At 19.50, the Grand Fleet was ordered south, while around 24.00 the Harwich Force was ordered north. At 03.50 on the 25th, the small cruiser Rostock, leading the torpedo boats of the raiding force, sighted the Harwich Force to the south-west, which attempted to lure the German force away. It was unsuccessful in this, and the I. SG fired on Lowestoft between 04.10 and 14.20, destroying 200 houses and two defensive gun batteries. Fog hindered the follow-on firing against Yarmouth, and the bombardment was broken off, since the force’s cruisers and torpedo boats were now in action with the Harwich Force, and required big-gun support.

The light cruiser Conquest was hit by a 30.5cm shell, which killed twenty-five and reduced her speed to 20kt, while the destroyer Laertes was hit in the boiler room, only just surviving. The Harwich Force then retired, but were not pursued by the Germans, who continued to hope that the British could be drawn into the arms of the battlefleet. However, while the Harwich Force turned to shadow at a distance, they were subsequently withdrawn, the Grand Fleet also abandoning any attempt at interception in view of slow progress in heavy weather. The British Battle Cruiser Fleet got within 43nm of the Germans, but no closer.

As a result of the operation, the British 3rd BS was moved from Rosyth to Sheerness (with its King Edward VIIs supplemented by Dreadnought as flagship), as was the 3rd CS of Devonshire class armoured cruisers.

THE FLEET IN 1916

By 1916, although the High Seas Fleet still nominally comprised three battle squadrons, the II. Sqn was generally being employed on other duties, its ships spending much of their time as guard ships and in other secondary roles (e.g. acting as icebreakers). In particular, Preußen was detached from the squadron as a guardship in the Sound in April 1916, under the control of CinC Baltic. Lothringen, in poor material condition, was largely employed as a coast defence ship, before paying off in March 1916, although she would then be refitted to relieve Preußen in the Sound that summer (see p 129).

THE BATTLE OF JUTLAND4

The next bombardment sortie was planned to be against Sunderland, once again with the intent of drawing out a British force that could be overwhelmed by the German battlefleet, which would be waiting to the east. Submarines would be deployed off Scapa Flow, the Moray Firth, the Firth of Forth and the Humber, and north of Terschelling, while airships would act as scouts for the I. SG and provide reconnaissance against being surprised by the whole Grand Fleet. The operation was first planned for 17 May, then slipped to the 23rd owing to condenser issues with some ships of the III. Sqn, and then again to the 29th when it was found that further work was needed to finish Seydlitz’s mine-damage repairs. Bad weather then made airship deployment doubtful, and on the 30th it was decided to substitute a sortie into the Skagerrak for the Sunderland bombardment. The plan was now for the I. and II. SGs, plus three flotillas of torpedo boats, to attack Allied shipping in the area between Denmark and Norway, tempting out British ships, which would be attacked by German submarines, and then led towards the battlefleet. This was originally to comprise just the I. and III. Sqns, plus the IV. SG, the cruiser-leaders of submarines and torpedo-boats, and four flotillas of torpedo boats, but the II. Sqn (less the detached Preußen) was added at the last minute, in spite of the resulting lowering of the fleet’s maximum speed. König Albert was absent from the III. Sqn owing to condenser problems, while the new Bayern, although commissioned back in March, was still working-up.

The I. (right) and II. (left) Sqns at Kiel. The former is led by the Helgolands (still all with short funnels, dating the image to before 1913), while the latter displays a mixed line of Braunschweigs and Deutschlands. (Author’s collection)

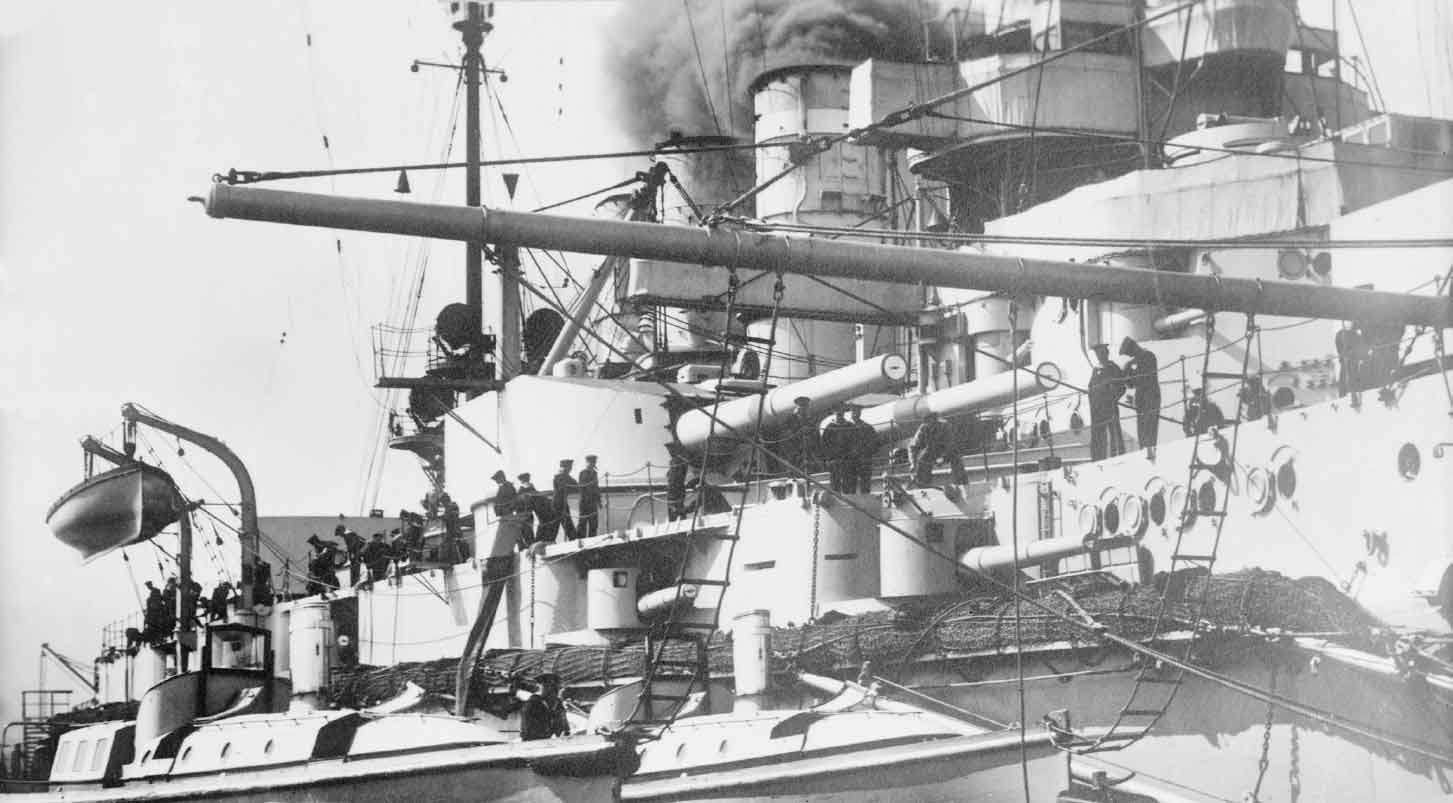

The starboard wing turrets of Ostfriesland; she was the only one of her class to fight at Jutland with short funnels. (Author’s collection)

The British had already planned a major operation for early June, but when signal intercepts indicated that the Germans were to begin some kind of operation on 31 May, the Grand and Battlecruiser Fleets were deployed on the 30th. As a result of some swapping of forces for training purposes, the Grand Fleet was missing its 5th BS (Queen Elizabeths), which sailed in company with the Battlecruiser Fleet, but had the 3rd BCS (Invincibles) instead. Three battleships and one battlecruiser were absent refitting or working-up, but the British forces comfortably outnumbered the Germans in capital ships, with an overwhelming preponderance in cruisers, but less of one in destroyers/torpedo boats.

The first forces to come into contact were the I. SG (with the flag in Lützow) and associated ships and the Battlecruiser Fleet, the catalyst being the despatch of light cruisers from both sides to inspect a Danish ship that happened to be sailing between the two sets of ships, the first shots being fired at 14.28, the first hit being scored by the small cruiser Elbing on the light cruiser Galatea at 14.36. The big ships first exchanged fire at 15.49, the first hits being scored by the Germans, Lion being hit three times by Lützow, the third shell putting her midships turret out of action, Princess Royal twice by Derff linger, Tiger nine times by Moltke, and Queen Mary and Indefatigable probably once each, by Seydlitz and Von der Tann, respectively. In return, Queen Mary struck Seydlitz twice, once forward and once on her aft superimposed barbette. The former caused considerable internal damage, which would later allow flooding to spread. The latter caused a hole some 80cm in diameter in the ring-bulkhead, with splinters entering the working chamber, where the turret mechanisms were disabled and two charges ignited. The flash from these entered the turret itself and spread down the main trunk, but lessons learned from the similar damage sustained at Dogger Bank meant that the effects were not as catastrophic, although there were significant casualties. The magazines were temporarily flooded until the fire had been put out. Lion (probably) hit Lützow’s forecastle with two shells, causing a large hole – of little immediate concern, but which would become more significant later.

Between 16.00 and 16.10, no hits were scored by the British, but Lützow struck Lion three more times, while Tiger took one hit and Von der Tann hit Indefatigable with two successive salvoes that caused the British battlecruiser’s aft magazines to explode; she capsized and sank rapidly by the stern, leaving only two survivors. During the following period up to 16.30, Lion was hit yet three more times by Lützow, while at 16.21 Queen Mary, under fire from Seydlitz and Derfflinger had her midships turret knocked out; the ship suffered a magazine explosion five minutes later, apparently following two more hits, sinking with the loss of all but twenty of her crew.

The I. SG bore the brunt of the German fighting at Jutland. Shown at Scapa Flow in 1919 are Moltke and Von der Tann, the least damaged (but still battered) of the German large cruisers at the battle. Beyond may be seen the tripod foremasts of Hindenburg and Derfflinger, the latter mast fitted while repairing her Jutland damage. (Geirr Haar collection)

Seydlitz then switched her fire to Tiger (joining Moltke, which had hit her thrice more), and Derff linger to Princess Royal, which now took her first damage. Von der Tann was now firing at New Zealand and Barham, leading the newly-arrived 5th BS, and made a hit on each before her starboard wing turret broke down. In exchange, Barham hit her at 16.09 around the starboard aft waterline, causing flooding that included the stern torpedo flat and threatened the steering gear. Von der Tann’s forward turret was permanently disabled by a hit on the barbette from Tiger at 16.20; a further shell from the same ship struck the hull abreast the aft barbette at 16.23, jamming that turret and starting a fire that was not fully extinguished for some hours. The turret was restored to hand operation around 20.00, but for the time being the ship was left with just the port wing turret, on the disengaged side, with extremely limited arcs to starboard and by 16.50 itself showing indications of the same kind of problem that was afflicting the starboard turret, so that by 17.00 Von der Tann was down to one 28cm gun out of eight.

Lützow had been hit twice by Princess Royal at 16.15 (causing no serious damage), while Moltke was hit at 16.16, 16.17, 16.23 and 16.26 by 15in [380mm] fire from Barham and/or Valiant, all on the hull. The first struck below S5 15cm gun, which was jammed, with its whole crew of twelve killed in an ammunition fire; the two adjacent 15cm guns were temporarily put out of action. The second shell dislodged an armour plate, admitting water above the armour deck, the third and fourth both causing flooding of starboard wing compartments. The resulting list having been removed by counter-flooding, Moltke had ~1000t of water in her hull and a trim by the stern, but was able to maintain her speed until the end of the battle. Seydlitz was hit on the forecastle by a 15in shell at 16.50, which would impact longer-term watertight integrity. She had also taken a 13.5in hit at 16.17, just abaft the aftermost starboard 15cm mounting, killing that gun’s crew and causing much damage, including to ventilation trunks. Smoke from the hit penetrated the starboard engine rooms, the low-pressure turbine room being temporarily evacuated.

The German battlefleet came within visual range at 16.30, and began to deploy at 16.42. König, Großer Kurfürst, Markgraf, Prinzregent Luitpold and Kaiserin opened fire against the British battlecruisers at 16.48, but the range was too great; the rest of the III. Sqn and the I. Sqn fired against the light cruisers of the 2nd LCS, although the only hit was on Southampton, probably by Nassau.

At 16.44, the I. SG had begun to fire on the 5th BS, Barham being hit, while the Battlecruiser Fleet re-engaged at 16.49, its destroyers making abortive attacks on Lützow and Derfflinger, all torpedoes missing, although a few 4in [102mm] shell hits were made. However, at 16.57, Seydlitz was struck by a torpedo fired by either Petard or Turbulent. This hit on the starboard side below the belt, abreast the fore part of the forward barbette, leaving a hole 12m x 4m and displacing part of the belt upward by ~23cm. The torpedo bulkhead held, albeit bulged and leaking, with the starboard wing compartments flooded over a length of 28m, and later spread a further 6m. For the time being, the ship remained in the line and was able to maintain speed, but over the next four hours flooding increased, the shell-hit at 15.55 allowing more water to enter, while leak-paths such as voice-pipes and cable-glands meant that the 19.5m section before the boiler room bulkhead flooded. It is also possible that the situation was exacerbated by faults in the repairs to her Lowestoft Raid mine damage.

Around 17.00, Lion was again hit by Lützow, and over the next ten minutes was struck twice more, while Seydlitz managed a hit on Tiger and Derfflinger hit Barham four times. König seems to have hit Malaya, but with her single gun, Von der Tann had little chance of hitting anything (although the second gun was soon brought back into service), while Markgraf, Prinzregent Luitpold and Kaiserin of the III. Sqn were also unsuccessful at this point. In the meantime, Kaiser, Prinzregent Luitpold, Kaiserin, Ostfriesland, Nassau, Thüringen, Rheinland and Westfalen had been in action against the 2nd LCS, although without scoring any hits.

From the British side, Seydlitz was hit by three 15in shells from Barham and Valiant between 17.06 and 17.10, the first two on the forecastle, the first opening up yet more holes in its structure, in the outer skin and the upper deck, the second holing both the forecastle and upper decks; splinters pierced the main deck. Together, these two hits ensured that more water could enter the forepart of the ship, progressive flooding meaning that by 21.00 the hole in the hull caused by the 17.06 hit was close to the waterline. The third shell struck the right side of the starboard wing-turret, holing the armour and disabling the right gun.

Lützow was also hit by the British pair at 17.13, on the belt below the waterline, causing minor flooding, and at 17.09 and 17.10 Warspite and Malaya scored hits on Großer Kurfürst and Markgraf. The former ship was struck by fragments from a near-miss, while her sister had shells pass though her starboard derrick-post and foremast, plus a third which struck 200mm armour, on the waterline, 23.5m from the stern, wrecking the wardroom and a number of cabins, buckling the main deck and causing ~400t of water to enter the hull. Around 17.30, two British destroyers, disabled earlier on, were blasted to pieces by almost the whole German battleship force.

The British battlecruisers did not fire again until 17.41, but the 5th BS kept up the exchange with the I. SG and III. Sqn, at 17.19 hitting Derfflinger on the side of the forecastle, the shell damaging the main and lower decks and a transverse bulkhead, and causing a fire. Although above the waterline, the holes in the bow plating scooped up water from the bow-wave, contributing to the 1400t of water that would eventually find its way into this part of the hull. Lützow received hits at 17.25 and 17.30, the first destroying the radio room and the second causing temporary disruption to the transmitting station. Von der Tann’s remaining turret broke down of its own accord at 17.15, leaving her without guns larger than 15cm until 18.30, when the turret was once again operational. Malaya was hit by seven shells between 17.20 and 17.37 and significantly damaged, a propellant fire coming close to destroying the ship. Soon afterwards, at 17.44, Southampton and Dublin attacked König, which received four 6in [152mm] hits, without hitting her assailants with any of six salvos; the same was true of the other III. Sqn ships that fired on the 2nd LCS.

The resumed action by the battlecruisers was largely ineffective, except for a hit on Lützow by (probably) Princess Royal at 17.45, which caused minor damage abeam the conning tower. Lion was hit yet again by Lützow at 18.05, but around 17.55 the 5th BS hit both Derfflinger and Seydlitz. The first-named may actually have been struck by two shells at once, on the 100mm armour of the bow, near the waterline forward of the hawse-pipes. Plates and decks were distorted, with 250t of water entering immediately, with more later, also probably combining with that entering as a result of the 17.19 hit.

Seydlitz was struck by three shells at 17.57, which further undermined the watertight integrity of the forward part of the ship and caused a fire. By 18.03, sufficient water had entered above the armour deck that the forward section of the ship was no longer buoyant, although the areas under the deck remained dry for the time being. At 18.03, König was slightly damaged by a fragment from a near-miss from Warspite or Malaya.

Since 17.30, the 3rd BCS had been making an approach from the east, its accompanying cruiser Chester skirmishing with the II. SG, and leading it into the arms of the battlecruisers: Wiesbaden was hit and immobilised by Invincible and Indomitable, while Pillau temporarily lost boiler power after a 12in hit from Inflexible.

The first contact between the main body of the Grand Fleet and the German forces was around 17.50, when the 1st CS armoured cruisers Defence (flag) and Warrior exchanged shots with the II. SG, hitting the stationary Wiesbaden, whose plight was increased through being hit by a destroyer torpedo. At 18.13, the armoured cruisers, now joined by their squadron-mates, Duke of Edinburgh and Black Prince, came under fire from König and Seydlitz, soon joined by Lützow, Großer Kurfürst, Markgraf, Kronprinz, Kaiser and Kaiserin. Defence was hit aft at 18.19, detonating the aft 9.2in magazine, the flash then spreading along the ammunition passage to the 7.5in magazines as well, and sank within a minute, with no survivors.

Warrior was also under heavy fire, although Markgraf also fired at Princess Royal, hitting her twice at around 18.22. The armoured cruiser received some fifteen hits from heavy guns and caught fire; she would probably have been sunk then (she foundered the next day) had Warspite not suffered a steering failure at 18.19, which caused her to circle in a way that took her closer to the German fleet, inadvertently interposing herself between them and Warrior. Warspite then became the target for Friedrich der Große, König, Helgoland, Ostfriesland, Thüringen and Nassau, being hit thirteen times, albeit without serious results.

The British 1st BS opened fire at 18.17, their first target being the unfortunate Wiesbaden that, nevertheless, remained afloat until the early hours of the following morning. It was not until around 18.35 that the main Grand Fleet had any success against the German big ships, when seven shells from Iron Duke and one from Monarch hit König. Amongst the results were a fire in P1 15cm casemate and a hole in the torpedo bulkhead abreast the forward superimposed barbette, with a propellant fire in the 15cm magazine beyond, although the incoming flooding soon put this out. Some 500t of water entered the ship, causing a list and necessitating counter-flooding. The shot from Monarch hit the casemate armour a little further aft, which contributed to a decision to flood the 15cm magazines in the area, water from which also penetrated the adjacent 30.5cm magazines. Orion (probably) also hit Markgraf at 18.35 on P6 15cm casemate, killing most of the crew and disabling the gun; the ammunition hoist for the corresponding starboard gun was also put out of action.

However, the 3rd BCS had been even more effective, Invincible and Inflexible hitting Lützow eight times between 18.26 and 18.34, following on from two hits by Lion around 18.19. The latter, although causing a fire, had little effect on Lützow’s fighting ability, but two of the 12in from the 3rd BCS caused major injury, striking below the waterline and flooding the broadside torpedo flat, from which water soon insinuated itself into other compartments via damaged bulkheads and other leak-paths, resulting in ~1000t being taken aboard rapidly. Two further shells struck near the bow torpedo flat, flooding it and adding to the water already streaming in further aft. Together with her 17.13 hit, some 2000t of water was now inside Lützow, her draught forward having increased by 2.5m, with her speed temporarily reduced to 3kt to minimise the strain on the leaking after bulkhead of the broadside torpedo flat. The remaining 12in hits holed the forecastle deck and caused damage amidships.

Indomitable scored three hits on Derfflinger between 18.26 and 18.30, one bursting close to the waterline abeam P1 15cm casemate, causing some leakage. The second shell hit the belt between the after two turrets, causing flooding of the wing passages over a length of 7.5m, the third on the belt just aft of the aftermost turret, damaging the torpedo-net stowage, and necessitating a short stop to prevent the propellers being fouled. Indomitable also seems to have hit Seydlitz around 18.34, the shock disrupting her steering gear for a while. 6in hits were also made on Lützow, Derfflinger and Seydlitz by the 3rd LCS.

Lützow and Derfflinger had been firing on Invincible for some minutes when, at 18.32, a hit on her starboard wing-turret led to flash penetrating the magazine and it exploding, breaking the ship in two. Only six of the crew survived. However, Lützow was now too badly damaged to remain as I. SG flagship, the flag shifting to the torpedo boat G39 at 18.56, and being eventually re-hoisted in Moltke around 21.00, after Seydlitz had proved too damaged to take on the role.

Realising that they were faced by the whole Grand Fleet, and not just the assumed detachment, the Germans initiated a reversal of course at 18.33, which was completed by 18.45, but was then reversed ten minutes later to confuse the enemy, which was at this point on a diverging course to avoid the threat of torpedoes – at 18.54, Marlborough, flagship of the 1st BS, was hit by one (perhaps from Wiesbaden). However, the further turn became congested, with the III. Sqn forced to all but heave to, while the British were able to once again sight and fire on the fleet: Großer Kurfürst was hit seven times, by Marlborough, Barham and/or Valiant. Two of the three 13.5in shells did no major damage, but the third allowed considerable quantities of water to enter the fore part of the ship on the voyage home, and the 15in hits caused major injury to the forecastle deck, knocking out P2 15cm gun and distorting various sections of the structure. The resultant flooding causing a list that required counterflooding, and eventually, Großer Kurfürst had over 3000t of water aboard. König and Markgraf each received a single 15in hit, as did Helgoland, with Kaiser taking two. Agincourt was responsible for 12in hits on Markgraf and Kaiser, while König was the victim of Iron Duke, a single shell causing considerable superficial damage; Helgoland seems to have been hit by Valiant, holing her forward belt, with 80t of water entering the ship. Markgraf’s hit caused minor damage and flooding, while the effects of Kaiser’s first hit was negligible, although the second pierced the upper deck, but without major injury. In response, Seydlitz, Markgraf, Derfflinger, König, Großer Kurfürst, Kaiser and Prinzregent Luitpold took the 2nd LCS under fire, without success.

A further reversal of course was thus initiated at 19.17 and, to distract the British, the I. SG was ordered at 19.13 to turn towards the British and attack; led for the time being by Derfflinger, all ships but the disabled Lützow did so. Although the battleship Colossus received two hits from Seydlitz at 19.16, causing slight damage, the I. SG came under the concentrated fire of the majority of the British battle line, with the Battlecruiser Fleet also joining in. Derfflinger was hit fourteen times between 19.14 and 19.25, first by a 15in shell from Revenge that struck the roof of the aftermost turret, causing a propellant fire which killed all but two of the turret’s crew. Shortly afterwards, another shell from Revenge hit the aft superimposed barbette, causing another propellant fire, killing all but six of the crew. All aft magazines and shell rooms were then flooded, smoke and gases penetrating all four engine rooms, which lay between the affected turrets. Revenge struck twice more aft, the second shell tearing holes of ~5m diameter in the upper and main decks; a further shell from her went through the upper part of the fore funnel without exploding. Five further 12in hits were scored by Colossus: one temporarily knocked out a diesel dynamo; one wrecked P3 15cm gun; one struck the belt and caused a leak; one hit the belt with little damage; and one caused damage to and under the quarterdeck. A single shell from Collingwood hit the superstructure abreast the bridge, causing considerable damage. Two 15in hits from Royal Oak soon after 19.20 did only superficial damage, while a 12in one at the same time from Bellerophon struck the conning tower, a splinter destroying the rangefinder of the adjacent forward superimposed turret.

Seydlitz took five hits between 19.14 and 19.27, the first four being of 12in calibre, one from Hercules destroying the aft starboard upper searchlight, another from the same ship destroying torpedo nets and causing some flooding. St Vincent struck twice, one shell piercing the hull plating abreast the bridge, damaging the battery deck and wrecking the sickbay; this damage added yet more leak-paths within the forward part of the ship. The second shell hit the already-disabled aft superimposed turret, causing significant internal damage. The fifth hit was a 15in shell from Royal Oak, which struck the right gun of the port wing-turret, putting the gun out of action; the left gun was left intact, but the turret could now only operate in local control. The hit also put P5 15cm temporarily out of action.

Von der Tann was only hit once, at 19.19 by a 15in shell from Revenge, which struck just aft of the after conning tower, splinters penetrating the viewing-slits killing or wounding everyone inside. Moltke, however, escaped unscathed. The already-disabled Lützow, now accompanied by seven protective torpedo boats, was also hit at this time, five 13.5in [343mm] shells from Monarch and/or Orion striking her between 19.15 and 19.18. One disabled the right gun of the foremost turret, another reduced the aftermost turret temporarily to hand-working, while a third caused the flooding of S1 15cm magazine. The remaining two hits respectively put the forward superimposed turret temporarily out of action and caused superficial damage in the area of P4 15cm casemate.

A torpedo attack was also launched on the British line, forcing it to turn away, both stratagems allowing the German battlefleet to withdraw under cover of smoke. The fleet was now sailing in reverse formation as compared to when battle had been joined, the II. Sqn being at the head, followed by the I. Sqn (with the flagship Friedrich der Große) and the III. Sqn; the I. SG rejoined at 20.00, sailing to the port of the battle line; its flag was still in G39, no opportunity having yet arisen to transfer it aboard Moltke. Lützow was limping along some way astern. The British forces had now turned and were sailing to the north-east of the Germans, the intent being to interpose themselves between the High Seas Fleet and home.

Action resumed at 20.19, when the British battlecruisers opened fire on the nearest Germans, the I. SG. Princess Royal hit Seydlitz twice, at 20.24 and 20.28, Lion hitting Derfflinger and jamming ‘A’ turret at 20.28 and New Zealand scoring three hits on Seydlitz just before 20.31. Princess Royal’s first shell put P4 15cm gun out of action and caused wider damage, the second damaging the bridge and forward searchlights. The three 12in hits were on the already-immobilised ‘D’ turret and on the hull armour, the latter causing the flooding of bunkers. In return, only a 15cm hit was scored on Lion. Some of the battlecruisers also fired on the I. and II. Sqns, splinters striking Westfalen and Hannover before New Zealand and Indomitable respectively hit Schleswig-Holstein and Pommern, the former also inflicting splinter damage on Schlesien. The extent of the damage inflicted on Pommern is unknown, but that on Schleswig-Holstein caused superstructure damage and disabled the starboard aft upper deck 17cm casemate, killing three. In the other direction, Posen hit Princess Royal at 20.32.

The British battleships never got in range at this stage of the action, and as it was getting dark, it was decided to postpone any resumption of battle until the morning, although ships of the 4th LCS launched a torpedo attack on the I. Sqn. The Grand Fleet was thus ordered to take up night cruising order at 21.17 – three parallel columns – and a number of cripples were sent home.

German arrangements for the night involved a single line, with the I. Sqn at the head, then Friedrich der Große, followed by the III. and II. Sqns, with Von der Tann, Derfflinger and the small cruiser Regensburg bringing up the rear. Moltke and Seydlitz were off to the west, towards the British fleet, as were the II. and IV. SGs; Moltke spotted the British 2nd Div (Orions) at 22.30, 22.55 and 23.20 and was herself spotted by Thunderer and the light cruiser Boadicea on the first occasion, but was not fired on. Seydlitz’s speed was now being reduced by her bow damage (exacerbated by steaming too fast earlier), and she lost touch with Moltke. Seeking a way past the British columns, the badly-damaged ship was spotted by Agincourt, Marlborough and Revenge, but not fired on, and eventually slipped through a gap between the 2nd and 5th BS, Seydlitz finding herself clear of danger and on her way back towards Germany by 00.12. Lützow meanwhile continued to limp southwards as her flooding continued to spread.

The flotillas of both sides were directed to undertake night attacks, leading also the skirmishes between them, as also occurred between the small and light cruisers, Frauenlob (the oldest ship in the battle) being sunk by a torpedo from Southampton. While the German torpedo boats were unable to find the British fleet, the British 4th DF managed an attack on the German line as it began to cross the British fleet’s wake around 23.30. Ships of the I. Sqn were spotted doing so by a number of British battleships, but not reported to the CinC, who was left with the impression that the sights and sounds of the 4th DF attack were only more skirmishes with light forces.