Chapter 11

Deciding on a 3D Printer of Your Own

IN THIS CHAPTER

Evaluating your needs

Evaluating your needs

Running a 3D print farm

Running a 3D print farm

Selecting a design

Selecting a design

Choosing print materials

Choosing print materials

Identifying key components and software

Identifying key components and software

Deciding what type, what size, and how much to spend on a 3D printer can be quite a confusing process. In this section I'll help you evaluate what's important for you in a desktop 3D printer so you can determine whether desktops either a) can deliver what you want or b) are not able to provide what a professional 3D-printing service could produce. If you decide that there is a suitable desktop option for your own 3D printer, I'll fill you in on what you'll need to be aware of and what materials and software will assist you with getting set up for desktop 3D printing.

The first step is to evaluate what you want to achieve with 3D printing. Do you just want to learn more about an interesting technology firsthand? Is 3D printing just something you want to tinker with? Are you intrigued by the possibility of being able to use a technology that may assist you in a hobby or the development of a new business idea? Whatever you need a 3D printer for, after you've evaluated your needs, I can walk you through the available options.

Evaluating Your 3D Printing Needs

When selecting a 3D printer, it’s good to first determine what you plan to do with it. Ask yourself, “What do I need a 3D printer for, and what am I expecting a 3D printer to do for me?” Often, the reply is “I don’t need it for anything in particular; I just want one.” This answer is absolutely fine. Let’s face it — 3D printers are exciting technology and well worth exploring just for the fun of it.

Another common reply is “I want to print parts and sell them.” This answer is one that a lot of people use to justify investing the time and money in a machine that can naturally make useful physical parts or artistic objects. One word of caution here: It takes a little time to achieve results good enough to sell, but this goal is a fine one that can drive you forward and the very one that’s already helped spread RepRap to every part of the world.

No single 3D printer can do everything; it's quite common for people to own multiple 3D printers that can handle different material types or have a specific purpose. If you want to print objects the size of a chair, for example, you clearly need a very large machine with a big nozzle. The level of detail may not be so important with a large object, but the print time will be a significant factor, so having a bigger nozzle and powerful extruder that can push a lot of molten plastic may be really quite important if you want to print big or strong functional parts. If, on the other hand, you only want to print jewelry samples and a very high level of detail is critical — and you also don't mind if it seems to take forever for a job to complete — then a resin 3D printer may suit your needs.

Do you want an open-source RepRap or another 3D printer?

After assessing your needs, you should work out whether you want just any 3D printer or specifically a RepRap (open-source 3D printer and eco-system). This distinction is important. Due to the demand for 3D printers, many companies have used the open-source RepRap technology to produce machine designs that can be traditionally mass-manufactured. It’s ironic that the success of a low-cost self-replicating machine now makes it so hard for manufacturers to keep up with demand that some companies choose to mass-produce parts. This situation leads to a few issues for customers. One problem is that if you can’t always reprint some of the parts for your machine, it’s harder to upgrade, repair, or self-replicate.

These issues aren’t problems, however, if all you want is a 3D printer and have little interest in RepRap’s self-replicating or sharing nature. Many machines can fill the bill, and almost all of them started from a RepRap branch or use its core technology. (Some machines’ manufacturers still class the machines as RepRaps, whereas others aim to hide those origins.)

RepRap is an open-source and open-community project. This means that all the design files, ideas, and digital documentation is shared as multiple free-to-use projects, even for commercial use. The RapRap community and its technology forms the basis for almost all new home 3D printers. RepRap stays vibrant and ahead of the game because of its diversity and the sheer number of dedicated, loyal users and developers in its worldwide community.

One of the core benefits of RepRap is the total control you have over making changes and enhancements to your printer. People and companies around the world make changes, upgrades, and enhancements of RepRap on a daily basis, so almost any improvement or enhancement you can imagine has already been implemented by one developer or another — someone who has probably made that improvement available to you.

This open-source concept isn’t just for machine-based improvements. You can also find upgrades for software, print material settings, and machine firmware (software running on the electronics of the printer), all of which can help you avoid a lot of frustrations. The print material settings in particular are becoming important areas for adjustment and tuning. (See Chapter 15.) Many consumer printer manufacturers, for example, lock down the settings of their printers so that you can print only with a specified material or at specified speed and quality settings. With a RepRap (or other open-source) 3D printer, however, you can print with simple settings or alter virtually any aspect of the machine. This flexibility becomes really important when you’re trying to create adventurous objects or want to print with new or unusual materials.

What is your 3D printer budget?

It's worth giving some initial consideration to the overall budget you are willing to spend to get set up with a 3D printer. The actual 3D printer is only the start, and that can cost anywhere from just $150 to more than $10,000.

If you have already started doing research or you read this book and decide that you want to go all-in with 3D printing, it's still well worth considering investing in a lower specification machine to start you off. The reason is that it can be a very steep learning curve for some of the very high-end machines that contain multiple tool extruders and offer many color 3D prints or have the ability to print in a wide range of material types. You can still explore a lot of this with a low-end machine, and it will teach you a lot along the way.

You can, however, print a lot of different parts with a 1Kg spool of material, but that's also a problem — if you start to print lots of different parts, it usually means you’re likely to need spools of material in multiple colors, types, or special finishes. This can quickly add up to a large investment in stock of plastic or resin and a lot of space to store all your different materials or colors.

Several other parts and tools are also often required; I fill you in on these in more detail later in this chapter.

Do you buy a ready-built 3D printer or assemble a kit?

In the early days of desktop 3D printing, you could often source a kit of individual component parts which were painstakingly assembled into a (hopefully) working machine. Then, after a lot of calibration, setup, and experimentation, you may have something that could 3D-print out objects. Nowadays, you can still buy kit machines that have lots of individual parts that will test your patience upon assembly, but it turns out that the meaning of the word “kit” has evolved. Some of the lowest cost so-called “readymade” models on the market are actually a kit of mostly assembled modules that you put together. It's not a great deal more difficult than assembling an Ikea set of furniture, so partially assembled readymades should still be a realistic option for you to consider.

So, should you buy a 3D printer or a kit? To answer this question, go back to your reasons for wanting a 3D printer in the first place. If you want to use it as a tool, and the physical output of a model is the only important factor, a fully built commercial machine with backup, support, and training available may be the way to go, but this route is more costly and (as I mention earlier in this chapter) somewhat limits what you can do with the machine. It’s also harder to get online community support, because the commercial models are not always the machines most people in the wider community are using, upgrading, and tinkering with. Thus, fewer people will have a desire to assist you, and to be fair, assisting you with problems is the job of the company that sold you the commercial closed-source machine.

If you are interested in the way a 3D printer operates, then it's a good idea to consider building up a kit machine or a semi-assembled model. If you’re feeling more adventurous you can source all the parts yourself and build up a custom machine or one of the many open-source RepRap designs. Building a printer yourself is still one of the best options in this phase in the evolution of desktop 3D printing. These machines are still highly mechanical, so parts will wear out; components will require careful calibration; and over the life of your 3D printer, you’ll run into all sorts of problems that interfere with your printing. Consider, however, that these same issues will occur with any 3D printer, no matter the cost; that’s the nature of the technology. For this reason, it’s often better to build your own machine and understand exactly how these parts work together to function as a 3D printer. When you’ve built your machine, you’re in a much better position to repair and maintain it.

Running a 3D Print Farm

You probably won't be running a 3D print farm straightaway unless you already have some experience with 3D printers. Maybe you (or your company) has decided to invest in a way to mass produce lots of 3D-printed parts in-house and you now need to either set up a farm or run it.

Setting up and running a 3D print farm is quite a straightforward task, but it does require some thought and consideration. In this section, I call on my first-hand experience running a small 3D print farm (around 20 machines) to offer some advice, some tips, and some tricks of the trade. (See Figure 11-1.) All that assembled wisdom should give you some key pointers if you ever need to run even 4 or 5 machines at a time or produce a lot of the same models over and over again. This section also shares a lot of general tips for good printing setup of multiple parts onto a build plate; it's well worth a read even if you have no intention of ever running lots of 3D printers together.

FIGURE 11-1: A simple small 3D print farm using many identical Prusa i3 MK3S+ machines that can share the same production files and produce identical parts.

Designing models for printing in a farm is probably one of the trickier aspects when it comes to running a farm. If you have ever printed any part over and over again, you probably noticed pretty quickly that a few small changes to the printing process could speed up the print time, make the print more reliable, reduce support material, and print in an orientation where very little postprocessing is required.

Before you make any decisions about what type of 3D printer to buy for a 3D print farm, first think about the maximum print time you can allow a set of machines to be running. For example, if you are working an 8-hour day, then you want all machines to finish before you go home. You need time to clean up the workspace and set up the printers for a new run the next morning, and then you need enough time after that to get another set of parts printed again before the end of the next day. Repeat that process a number of times each day, and you'll have a working print farm.

The time duration of a printed object is highly dependent on the print quality settings, the material being used, how large the object is, and its infill density, or you may just want to have multiple objects on the print bed. Luckily, we now have an accurate duration of expected print time in most slicing programs that can really assist to pack the most objects onto a build plate in the time you allowed for machine operation.

FIGURE 11-2: Two types of 3D print plates — the Prusa MINI (top) and Prusa i3 MK3 flexible magnetic quick-change PEI coated sheets (bottom).

Minimizing wasted plastic, reducing the need for support material and its subsequent removal from printed parts, and generally keeping any extra material you need to clean from the build surface at a minimum are good goals when designing parts destined to be printed on a 3D print farm. The more finished you can make a printed object, the less work you will need to do after printing and when it's time to prepare for another print run.

The choice of material is also quite important when talking about using many hundreds or thousands of filament spools. I personally recommend manufacturers who produce filament on sustainable cardboard spools or as a refill coil. (For more on that topic, check out Chapter 16.) Cutting down on single-use plastic waste is not only important, but it'll make your recycling life easier as well. Choosing a filament manufacturer with a high quality tolerance and consistent color from batch to batch will allow you to switch over empty filament spools mid-print and know that you can use multiple parts together without seeing a difference in the tone or color. Whatever you do, please test out materials before you buy a large batch. You may also find that matte finish materials assist with overall finish quality and can also help hide layer lines from the 3D-printing process of stacking layer-on-layer of plastic materials.

For practical 3D-printed parts, PLA and PETG are often more than adequate for many types of objects you may want to use a 3D print farm for. Figure 11-3 shows a range of electronic enclosures printed in PolyTerra matte PLA. All these parts were made on a 3D print farm.

FIGURE 11-3: Range of 3D printer electronic enclosures consisting of multiple parts.

Licensing and Attribution

RepRap is an open-source project. From the start, it had to be, because trying to limit or stop a machine that can duplicate a significant proportion of itself is an almost-impossible task. The open nature of RepRap provides huge benefits for sharing within the wider community of makers, designers, and users. Even better, this open aspect doesn’t limit the project to hobbyists or impair its use with closed-source machines; it does the exact opposite as long as you pay attention to the licenses used.

A typical hardware or software license details what you’re allowed to do with the files (designs, source code, assembly instructions, and so on) that are made available to you. The core of the RepRap project falls under the GNU General Public License. On the whole, this license means that the files are free and anyone can use them.

You can find the GNU General Public License at https://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html.)

The GNU license was designed for open-source software, not hardware projects. That makes using GNU for 3D printers possible but not ideal. This limitation is due to the fact that hardware projects have a physical presence that can be shown out of context from the original project or reused without obvious acknowledgment of the original.

Therefore, many of the hardware elements for RepRap, as well as the associated 3D designs or supporting electronics, are licensed under a Creative Commons license. The brain of most RepRap 3D printers, for example, is an Arduino electronics control board, a modular set of electronics used for all sorts of control projects and industrial tasks around the world. (You can find the Creative Commons licenses at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/.)

Arduino controllers are open-source hardware and software, licensed for use with the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license. This arrangement allows both personal and commercial use, but you must share the files the same way that Arduino does and also credit Arduino in the documentation of your design or changes.

A typical Creative Commons license uses a simple set of icons as a logo to indicate what type of license it is and what you can or can’t do with it legally. The license shown in Figure 11-4, for example, allows you to copy, distribute, or transmit the work; you're also free to adapt the work and make commercial use of the work it covers.

FIGURE 11-4: A typical Creative Commons license icon.

In the logo, the icon of the little person in a circle means that this license is provided on the condition that you attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor, and that you do not do this attribution in a way that suggests or implies that the author has endorsed you or the use of your work.

The SA icon means share alike, so all derivative work must be shared under the same license. In this case, the derivative work can also be used commercially. You wouldn’t be allowed to build onto this work and then change it to a noncommercial license to stop other people from building on it, for example.

The logo in Figure 11-5 specifies that work can be shared but isn’t licensed for commercial use (NC) and doesn’t allow derivatives (ND). You’re still required to attribute the work to the creator or licensor when you share it.

FIGURE 11-5: Icon of a Creative Commons license with more restrictions on commercial use.

If you obtain a 3D model under this license, you’re not allowed to sell a 3D-printed version of the model, publish modified versions of the design, or sell the model’s design files.

You can print and display the model as long as you get permission from the author and make the author aware whether the design or print of the model is helping you sell something else, such as a 3D printer that printed the licensed model. When you do so, it’s of the utmost importance to provide attribution to the designer, display the licensed name of the model, and show the license. Then you’re complying with the license terms, and the designer gets credit for the design, which is visible to anyone who sees the printed object on display.

When you don’t provide attribution, the license system breaks down, and the designer whose work you used this way will be less likely to share the next design (or to be very happy) with you.

Selecting a 3D Printer Design

When selecting a 3D printer design, don’t disregard some common RepRap 3D printers. You shouldn’t consider these established designs all out of date just because they’re not on the cutting edge; consider them to be stable ways to get started, sensible choices, and springboards to further adventures into understanding the history of 3D printing and how current machines are based on similar designs. All the 3D printers discussed in this section are based on established technology and have been widely used in the community. Updated versions of these models would be an excellent choice for your first 3D printer. If you have not yet chosen a 3D printer from the list in Chapter 10, or if you just need a little more background to help you make a decision, here is some further history about the RepRap origins of many desktop 3D printers available today.

RepRap and open-source designs

The evolutionary nature of RepRap is based on survival of the fittest, so many designs, modifications, and upgrades fall out of use or are superseded by newer designs as users and other developers adopt them. Watching a RepRap design grow and change, and even sometimes die out, is one of the joys of an open-source hardware platform.

The following list describes the most common designs for early RepRap 3D printers, in approximate chronological order (subject to innovation):

Mendel: The original Mendel printer was designed by Ed Sells at the University of Bath in the United Kingdom. After the original design (named Darwin after the biologist Charles Darwin who developed the theory of evolution to explain biological change) started replicating at various universities around the world, Mendel set a new standard for RepRap printers that’s still strong and used today in many derivative machines. The Mendel concept is Cartesian, much like existing 2D printers or plotters in its operation. As I describe in Chapter 10, most Cartesian-based machines move the print bed back and forth along the Y axis, move the printer carriage from side to side on the X axis, and lift or lower the entire X axis and printing carriage on the Z axis (usually with two motors, one on each side). The original Mendel printer is now considered to be overly complex to build, but modern versions of the Mendel have become popular and account for a high proportion of the RepRap 3D printers built by users.

The Mendel 3D printer is a pain to build. It has around 1,500 individual components and is over-engineered compared to the two following models. It's a good reference point for the technology that blossomed into almost every desktop machine on the market today, but it's just a little too complex to build and run every day.

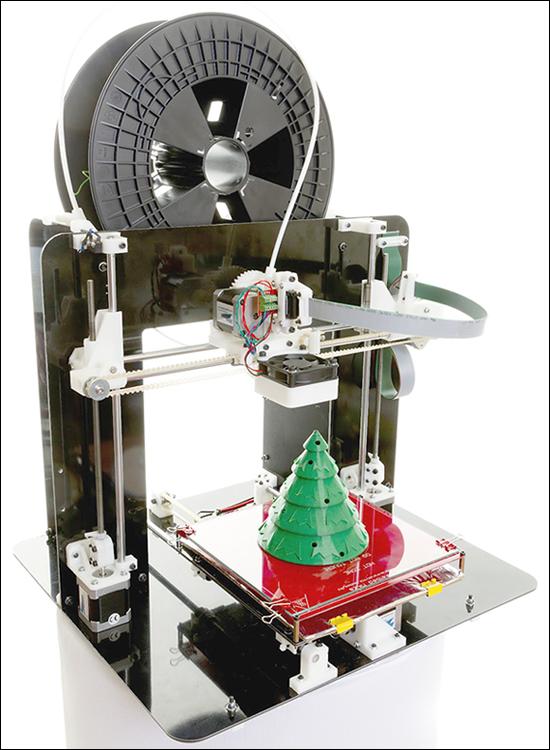

The Mendel 3D printer is a pain to build. It has around 1,500 individual components and is over-engineered compared to the two following models. It's a good reference point for the technology that blossomed into almost every desktop machine on the market today, but it's just a little too complex to build and run every day.- Prusa Mendel: The most widely constructed and widely used RepRap 3D printers are the Prusa Mendel and its many derivatives. (A modified Prusa Mendel is shown in Figure 11-6.) This machine, designed by Josef Prusa, is a simplified version of the original Mendel design that proved to be highly popular. Version 2 of the Prusa Mendel is still built today and is highly recommended as a first machine.

- Mendel90: This machine (see Figure 11-7) is a variant on the Mendel design that has a rigid frame (usually made of laser-cut wood) and plastic acrylic sheet or laminated DIBOND material as the main structural elements rather than the traditional RepRap threaded rods used in the Prusa machines. It uses almost all 3D-printed parts apart from the main structural frame, which is often manufactured from an aluminum-and-plastic DIBOND laminate. Mendel90 was designed by Chris Palmer (also known as Nophead), one of the original RepRap team members. He shares a vast amount of RepRap and 3D-printing information on his Hydraraptor Blog (at

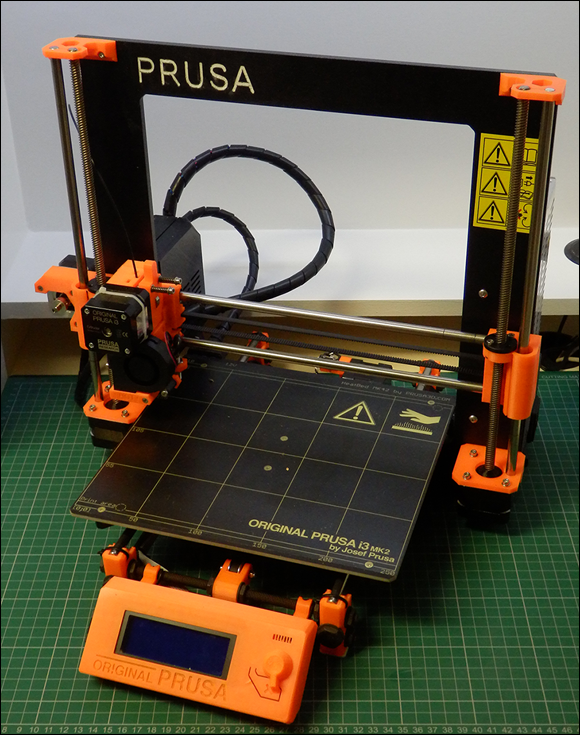

http://hydraraptor.blogspot.com). This blog is an essential read for anyone who wants to understand the history, challenges, success, and failures of 3D printing at home. - Prusa i3: The Prusa i3 (MK2/MK3/MK4) has a hybrid design that combines elements from the Mendel90, Wallace, and other machines to make a simple-to-build, high-quality home 3D printer. Version 3, known as i3, is a revised version of Mendel, similar in concept to Mendel90 but with a rigid central wooden, acrylic, or aluminum frame and threaded rods that support the moving bed on the Y axis. (See Figure 11-8.) The Z motors are also positioned at the base as in the Mendel90, which provides Z axis movement with a flexible coupler to create smooth print sides. Overconstraint in previous designs (forcing alignment to a threaded rod that could be bent or worn, rather than allowing for some self-centering freedom on the Z axis vertical movement) often produced Z-wobble, which appeared as bands or grooves on the side of a printed object. The Prusa i3 continues to be updated and improved. (For more on the Prusa i3, see Chapter 12.)

- Huxley: Huxley is a miniature version of the Mendel that uses smaller components (6mm rods for the frame rather than 8mm, for example) and uses smaller 3D-printed parts for its construction. The build area is smaller than the Mendel’s but large enough for many applications. The machine is also wonderfully portable. Like the original Mendel, the first Huxley machine was designed by Ed Sells at the University of Bath. Huxley was an unofficial project until it was unveiled to Adrian Bowyer and then published as an official RepRap printer. The Huxley wasn’t as popular to start with as its bigger brother Mendel, mainly because many people were trying to build their first 3D printers and opted for the more mature Prusa Mendel design. The Huxley was redesigned by Jean-Marc Giacalone as the eMaker Huxley and sold fast, quickly becoming one of the most popular kits available.

Image courtesy of Adrian Bowyer

FIGURE 11-6: Prusa RepRap 3D printer, Version 2.

Image courtesy of Alan Ryder

FIGURE 11-7: A Mendel90 RepRap 3D printer.

FIGURE 11-8: The Prusa i3 3D printer.

Wallace/Printrbot: The Wallace (see Figure 11-9) and the Printrbot have similar configurations. Only the Wallace can be considered a true RepRap, however, because its parts are still produced by printing. The Printrbot’s ability to self-replicate has become increasingly more limited. For example, it initially required the use of a wooden laser-cut framework, but it now uses fully stamped and folded sheet metal structures. This approach allowed the production of very low-cost kits and ready-built machines, some specifically designed for educational purposes.

Version 2 of the open-source Printrbot Jr printer, designed by Brook Drumm, is built on RepRap technology and constructed of laser-cut plywood. Due to its mass-manufactured, laser-cut frame, it’s one of the least expensive ways to get a home 3D printer. Its motion elements improve its printed output.

The Printrbot can’t print another Printrbot. Its intricate, interlocking framework is designed to be cut by a computer numerical control router (CNC) machine or a laser cutter. It can’t be easily reproduced by hand, in other words. Wallace, on the other hand, can replicate much of its own structural framework and requires only a simple bed-cut square. A RepRap, however, is designed to allow the 3D printer to manufacture the complex parts and have you, the builder, source all other components locally or easily produce them yourself by hand using standard tools or materials. You should not require a tool-shop or manufacturing facility to produce RepRap 3D printers.

The Printrbot can’t print another Printrbot. Its intricate, interlocking framework is designed to be cut by a computer numerical control router (CNC) machine or a laser cutter. It can’t be easily reproduced by hand, in other words. Wallace, on the other hand, can replicate much of its own structural framework and requires only a simple bed-cut square. A RepRap, however, is designed to allow the 3D printer to manufacture the complex parts and have you, the builder, source all other components locally or easily produce them yourself by hand using standard tools or materials. You should not require a tool-shop or manufacturing facility to produce RepRap 3D printers.Many other RepRap-based designs are available to print out yourself (like my 3DR Delta printer) and even pocket or suitcase printers that can fold flat to store and flip up to allow for a well-sized build area. There are far too many to list here, and, at this point in desktop manufacturing, there is also a very wide choice of ready-made machines that I want to talk about next. If you do, however, want to browse the many different RepRap 3D printer designs, then do take a look at

www.reprap.orgfor more inspiration.

FIGURE 11-9: A RepRap Wallace printer, designed by Rich Cameron as a RepRap 3D-printable version of the Printrbot style of minimal design.

Home 3D printer modular kits and self-sourcing

If building a RepRap 3D printer from raw components and printed parts is not to your liking, a host of home 3D printer modular kits are also available. Whether you want a kit with a lot of ready-made 3D-printer parts or a kit with few of them comes down to budget and personal preference. All the kits use a similar set of RepRap control electronics, firmware, and software slicing programs; all can achieve similarly high-quality print results with a little care and tuning.

Endless variants of Cartesian-based 3D printers are available. All the 3D printers in the following list can provide excellent printed objects; some are available in a modular kit of ready assembled sections that can be bolted together or individual components that will take a little longer to assemble yourself. Most kits will have a good construction manual to assist you and often a large community of users who can lend a hand or provide advice when you get stuck.

- Prusa MINI: This machine is one of the most popular kit form printers; it's small but very capable. An ideal first 3D printer. Available as a kit as well as mostly assembled sections, this machine has a smaller build area, but a lot of great features you may not find on other budget printers listed here. (You get a look at how to assemble and use the Prusa MINI in Chapter 13.)

UltiMaker: This 3D printer, based on RepRap technology, was one of the first kit machines to be sold. It uses laser-cut wooden panels to make a box frame and has a configuration similar to the early RepRap Darwin. The print bed only moves up and down, and a lightweight print head moves on the X and Y axes. The Ultimaker is not your father's Darwin, however, but a fast printer that introduces a Bowden-fed extruder. This method of plastic extrusion moves the mass of the motor and filament-drive system to a static position on the machine; then the filament being extruded enters a slippery PTFE (Teflon)-based tube that doesn’t allow the filament to bend, buckle, or compress. At the other end of this tube (usually, about 500mm long) you find the moving print head and the hot-end that melts the incoming filament being pushed by the remote extruder. This setup allows the very light print head to move very fast indeed to achieve faster printing and potentially higher accuracy compared to a heavier print head and extruder that can’t move as quickly. (I talk more about Bowden-fed extruders in the sections that follow.)

The Ultimaker Version 3 is no longer a RepRap. Success and increased global sales allow for traditional manufacturing methods of injection-molded parts and laser-cut plastic panels. It is, however, one of the highest quality and fastest 3D printers available for the desktop market. Ultimaker 3 also introduces a new concept in removable cartridge-style print heads, which allows for quick swapping of nozzle sizes and different print materials. Version 2 and Version 3 printers now come as fully assembled machines and are no longer available in kit form.

The Ultimaker Version 3 is no longer a RepRap. Success and increased global sales allow for traditional manufacturing methods of injection-molded parts and laser-cut plastic panels. It is, however, one of the highest quality and fastest 3D printers available for the desktop market. Ultimaker 3 also introduces a new concept in removable cartridge-style print heads, which allows for quick swapping of nozzle sizes and different print materials. Version 2 and Version 3 printers now come as fully assembled machines and are no longer available in kit form.- Prusa i3 MK2: This 3D printer (see Figure 11-10) is one of the last commercially available kits with significant global sales. It’s a great way to get into 3D printing because the assembly experience is enjoyable and educational. Many of the tricky parts are simplified in the MK2, MK3, and MK4 models. When buying a 3D printer kit today, you should receive a highly detailed manual and you’re usually not expected to solder or crimp connections. Simply assemble the mechanical parts and wire-up cables to matching connectors and set up software on a PC.

- Tantillus: The Tantillus looks a lot like a miniature Ultimaker, as Figure 11-11 makes clear. This 3D printer was originally designed to be a fully printable machine. In fact, original versions that don’t have the laser-cut frame have the highest percentage of printed components used in any RepRap printer. The case frame construction was originally fully 3D-printed. Another version, with a laser-cut acrylic case, was designed as an easier do-it-yourself kit in a successful crowdfunding campaign by Sublime. One unique feature is the use of high-strength fishing line instead of belts to provide the X and Y motion, resulting in a fast-moving machine and high-quality prints.

FIGURE 11-10: The Prusa i3 MK2 3D printer.

FIGURE 11-11: The Tantillus 3D printer.

Experimental designs

At any given time, the RepRap community has thousands of experimental modifications going on all around the world. Every now and then, a new branch sprouts. New or vastly different machines usually attract a lot of attention, and other developers may have to help refine them into something that can be used across the community.

Open innovation and the development of ideas into physical parts that enhance operation can be one of the most exciting aspects of the RepRap community. The aim in RepRap isn’t always to keep making things faster and more accurately; some of the most challenging design improvements come from thinking about lower-cost materials that are more accessible to more people. Other developers seek a new design that occupies less desk space but still prints large objects.

All the designs I’ve discussed so far in this chapter use the Cartesian coordinate positioning system. The next wave of popular home 3D printers uses the Delta triangulation-based coordinate system, as described in Chapter 10.

Many of the most successful branches of Delta 3D printer designs sprang from a proof of concept machine called the Rostock and an advanced design called the Kossel, designed by Johann C. Rocholl, who also further developed the Delta firmware branch of Marlin that is used in many RepRap Delta printers.

Following are the most popular Delta 3D printer designs:

- Rostock Max: This design (see Figure 11-12) is inspired by the original Rostock but has a laser-cut frame and makes innovative use of bearings that run on aluminum extrusions to provide the linear motion of the machine. It’s also one of the biggest machines on the market, capable of printing models of significant size. (You'll get a chance to look more closely at the Rostock Max kit in Chapter 12.)

- 3DR: I designed an alternative Delta printer, which uses mainly 3D-printed parts for the structure of the machine (see Figure 10-6 in the previous chapter).

FIGURE 11-12: A Rostock Max 3D Delta printer, designed by SeeMeCNC.

Choosing Print Media

With most desktop 3D printers, you have a wide choice of materials you can use for the build process. There is an even wider range you can use in paste form if you use the appropriate style of material extruder system.

Thermoplastic

Desktop 3D printers mainly use thermoplastics as the materials of choice for manufacturing objects.

This section lists some common types of thermoplastics. A 3D printer normally uses polylactic acid (PLA), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), or polyethylene terephthalate (PET), but developers are experimenting with many other interesting materials. Some of the materials are designed for a specific purpose or aspect, such as temperature, strength, flexibility, optical clarity, or impact resistance. Other materials are simply designed to look good when they’re polished after printing.

When a thermoplastic is processed for use in a 3D printer, it’s usually produced in a factory with specialized plastic extruding equipment and new material. The material, when extruded as a tightly controlled plastic wire (round in cross-section), is called filament. 3D-printing filament is commonly available in standard 1.75mm diameter and a much older standard of 2.85mm. Machines that use 1.75mm are recommended as this will allow you access to the widest range of materials. 3D-printing filament originated in the automotive plastic welding industry.

Although many suppliers use new materials in their filaments, the use of recycled plastic, or regrind, is a fine goal for 3D printing. One day, you’ll be able to recycle plastic milk cartons and packaging to use in 3D printers. Many projects have been started with the aim of producing a system that can manufacture filament at home. Presently, however, creating regrind is a slow and complicated process. At the time of this writing, it’s still easier and less expensive to buy ready-made filament on the roll.

Other, less common thermoplastic materials include nylon and mineral-filled LayBrick, a plastic- and chalk-filled material useful for architectural models. Another option is laywood or woodfill, which is PLA blended with 40 percent wood fiber (which I cover in more detail in the composite section later in this chapter). Laywood or WoodFill can be painted, drilled, tapped, and sanded much the same way as woods such as Medium Density Fiberboard (MDF).

PLA/PHA plastic

PLA is one of the most common types of 3D-printing filament. PLA plastic is manufactured from cornstarch; during the process, the lactic acid is polymerized. The resulting thermoplastic has been used in industry for many years. PLA is used for candy wrappers, coffee-jar lids, and many other products.

PLA can be recycled and starts to break down when exposed to industrial composting facilities. Because PLA is a nonpetrochemical plastic (not formed from oil), it’s regarded as an eco-friendly choice.

PLA has a low glass transition temperature of 60°C, which is the point at which the material starts to turn from a solid to a liquid. The glass transition point is also the temperature used by a 3D printer’s heated bed to hold a model in a stable state while it’s being printed. Matching the glass transition point of a material is often critical to keep the part securely attached to the build platform during a print and also to minimize the warping effect caused by accumulated layers of melted plastic. (Figure 11-13 demonstrates how even large objects can resist warping.)

FIGURE 11-13: Large objects like this vase can be produced in PLA plastic without significant warping.

Another critical temperature to know in 3D printing is the useful melting point —when it's at a liquid state and can flow. For PLA, that temperature is around 160 ° C. A temperature between 160 and 210 ° C is often used for 3D printing with PLA. At a higher temperature, the plastic is too flexible for 3D printing and also starts to break down.

Fans are often used to cool the print layers during printing with PLA. This arrangement may sound like a bad idea, but for small prints being done very quickly, it’s usually the only way to ensure that a layer is cool enough to allow the next layer to be added. Otherwise, you end up with a plastic blob rather than the object you had in mind. Also, using fans can minimize the curling of an object’s printed edges, resulting in better overall surface quality.

Melting PLA produces a sweet smell something like cotton candy or popcorn, which makes it well suited to printing in a home environment. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) is similar to PLA but is made from fermented sugar rather than the cornstarch used in PLA. The formation of lactic acid isn’t required, so the manufacturing process is more straightforward. PHA is starting to become more common, and you may also see blends of PLA+PHA.

PLA and PHA plastics in natural form are semitranslucent but can be altered with pigments into a wide range of translucent and opaque colors.

A heated build platform isn’t essential for using PLA. If you expect to do your print jobs at room temperature, you can use a cast acrylic platform or various types of tapes and adhesives to print smaller parts successfully. For objects measuring 130mm or more, however, a heated platform is recommended and is now almost always included as standard on even entry level machines.

ABS

ABS is another common choice for 3D printing. Being oil-based, it’s not eco-friendly like PLA, but it has the advantage of a much higher glass transition temperature. For parts and objects that are going to be subject to temperatures up to 100 ° C, ABS may be advantageous.

A heated build platform is essential for printing with ABS. A minimum temperature of 100 ° C is required for the platform, and a temperature around 240 ° C is required for the extruding nozzle.

Natural ABS is off-white but can be processed as clear or colored during manufacture via techniques similar to those used for PLA. ASA is similar to ABS and is now often more readily available as a filament for 3D printing.

PET / PETG

PET is quickly becoming the go-to material for many 3D print users. It can be a very good alternative to ABS and PLA because it has similar impact resistance to ABS and higher temperature resistance than PLA. It usually has less odor during printing and warps significantly less than ABS. PET plastic is used for many types of plastic packaging, especially food and drink containers. PET can be produced in many different forms, but the most common types are PETT and PETG. For PET materials used by 3D printers, the generic term polyester is often used. Look for brand names such as nGen from ColorFabb, which uses Amphora co-polyester from Eastman. nGen filaments are specifically formulated for 3D printing.

Another popular PETT polyester is t-glase from Taulman3D. This material is designed specifically for 3D printing. Generic polyester filament is often based on PETG, a glycol modified polyester. Although this material is often great to use for large models for which PLA may be too brittle, it can exhibit more warping issues and even damage some glass build platform surfaces.

A heated build platform running at around 85°C is ideal for printing with polyester or co-polyester based materials. Fans can be used for cooling the extruded material in a similar way to cooling PLA.

Natural polyester is usually supplied as a clear filament but can be tinted or colored opaque during manufacture. PET bottles with the recycling symbol 1 can be ground and melted to produce recycled materials for 3D printing. As polyester is the world’s third-most-produced polymer material, it causes significant environmental problems in places where many plastic tubs and bottles wash up from the sea. Several not-for-profit companies seek to recycle these waste plastic containers into 3D-printing filaments or other plastic products.

Composite or filled materials

You now also have a choice of more exotic 3D-printing materials, which often have a PLA or polyester base material and some solid fiber material (usually, less than 20 percent) mixed in. The most common composite material uses added wood particle fibers. The wood can be cherry, oak, bamboo, cork, or recovered waste wood. 3D models printed with wood filament are mostly plastic but create a wood effect and can be sanded, drilled, and even varnished.

The next-most-popular composite filament contains metal particles — anything from iron (which can be rusted after printing) to stainless steel and brass (which can be polished after printing to simulate solid shining metal). Copper, aluminum, bronze, and other metals are also available, often supplied on smaller rolls of filament; they cost significantly more than standard plastic filament does.

Metal filaments behave much like thermoplastic when printed. They may be much heavier and more expensive than plastic due to the metal content, but they’re not as durable as real metal objects. Sanding and polishing of the surface need to be done by hand (or with a small rock tumbler) very carefully, so that the base plastic doesn’t melt. After some significant manual effort, you can achieve great results with metal-filled materials. Unless you plan to polish, rust, or smooth the materials, however, using them may not be worth the extra cost if you’re only looking for a metallic color.

Carbon fiber is another popular composite filament. The short carbon fibers add strength, resulting in a ridged matte finish on the printed part, but the object won’t be nearly as strong as a traditional molded or layered carbon fiber object. Developers are experimenting with other filler materials and even with fragrances, such as coffee, pine, and strawberry.

Most filled composite materials produce a slightly rough finish. Composite materials often can’t reproduce fine features that a non-composite filament can achieve. Composite filaments also have a greater tendency to ooze or string during printing.

In recent years even foaming materials can now be 3D-printed. These expand as they are heated, forming a lightweight foam object, ideal for aircraft and drone models and cosplay armor or anywhere you need strength and a lightweight model.

Paste

Paste materials can be used in 3D printers that have a modified extruder — usually, a syringe or other type of cylinder. Such extruders press out the paste material in much the same way that you press cake icing from a piping bag. Syringes are often chosen for being food-safe, but don’t reuse these syringes for different materials or try to use a normal thermoplastic extruder.

All sorts of food-based materials can be used in a 3D printer with an appropriate extruder, but the paste must have the consistency of toothpaste so that layers can be built up on top of one another. Frosting, marzipan, cookie-dough mix, and masa (Spanish dough used to make tortillas) are ideal candidates for 3D printing. Chocolate is a much more complex material for 3D printing, but you can print chocolate items at home. If you pay close attention to temperature and cooling methods, you can provide some wonderful possibilities for decoration and customize cakes and treats for loved ones and friends.

In addition to foods, almost any other material in paste form can be used as a 3D-printing material. Cements, fast-setting resins, ceramics, and even precious-metal clays can allow you to produce traditional artistic objects from solid materials (see Figure 11-14). (You can get a closer look at the paste extruder in Chapter 14.)

FIGURE 11-14: Fine porcelain clay can be printed with a paste extruder and then fired in a normal kiln to produce ceramic.

Identifying Key Components

Like the very early home computers, many early home 3D printers were available in kit form. Although assembling the parts is relatively straightforward, the build can be a little daunting unless you visualize how all the components come together to produce a working 3D printer.

Structural framework

The framework of a RepRap 3D printer is usually a material that’s commonly available in many countries, which is one of the ways that RepRap makes 3D printing accessible to many people. Common threaded rods, such as M8 and M10 size, are often used as the framework. Some printer kits use laser-cut wooden or aluminum plates for the entire frame structure. Extruded aluminum tubes (often used for industrial racks or production equipment) can also provide a strong and lightweight framework for a 3D printer.

Extruders

The extruder and hot-end of a 3D printer are the most critical parts to ensure good quality and reliable printing. The last thing you want, after seven hours of an eight-hour print, is for the extruder drive to strip the filament or the hot-end nozzle to jam. These issues stop the flow of plastic and ruin your printed object. If you have too many of these problems, your new 3D printer will spend most of its time turned off or in a constant state of being fixed.

The most common style of hot-end has an aluminum heat sink and a brass nozzle with a small hole (typically, 0.4mm or 0.5mm). The small nozzle is where a stream of molten plastic is extruded onto your build platform layer after layer. Brass is often used, as it’s easy to machine, wears well, and provides adequate heat conduction. Brass is also forgiving: If a separate screw-in nozzle end is brass, you’re not likely to damage it. A stainless steel or high-temperature plastic section separates the heated nozzle from an aluminum heat sink, which is usually cooled to prevent the plastic filament from swelling and jamming before reaching the hot nozzle and melting into a controlled bead of molten plastic extrudate. Aluminum transfers heat quickly and can improve print speed, but aluminum hot-ends are rare.

The extruder nozzle can be screwed into a heating block or these two parts may be integrated and machined as one part. The heating block contains a heating element, which is usually a cartridge heater. A temperature sensor (usually, a thermistor) is also required to provide a closed-loop sensing system. The electronics can control the heating of the material being extruded to within a few degrees.

Another feature that every hot-end needs is a way to isolate the heating block from the incoming filament feed. This feature is fundamental, and if it’s not carefully designed and accurately crafted, materials will jam. This section of the hot-end is called the thermal break. Commonly, the thermal break is made from a hollow stainless-steel tube or a high-temperature plastic such as PTFE (Teflon) and PEEK. PTFE has low friction against the incoming filament, which is important because as soon as the filament starts to reach its glass transition temperature, it acts more like rubber, gripping the walls of the cold-end. The cold-end holds the heating block in place and serves as an insulator, impeding the transfer of heat. Keeping the cold-end as cool as possible is critical. One common technique is to use a small fan to blow cool air against the cold-end and help maintain good thermal isolation between cold-end and hot-end.

Many types of RepRap hot-ends are available. Each type performs much the same job, but some designs are best suited to particular machines. The most common hot-ends include the following (see Figure 11-15):

- E3D: This nozzle is designed for high-temperature materials and a very low degree of ooze, so it’s excellent for accurate and fine printing.

- J-head: This good all-around design is limited to temperatures below 250 ° C because of the materials used. The J-head nozzle has more parts than the newer stainless-steel designs but is easy to use and service. Figure 11-16 shows assembled and exploded views of this nozzle.

- eMaker Bowden: This hot-end is used in the small Huxley printer.

- Prusa V2: This nozzle uses a stainless-steel barrel with aluminum cooling fins and can reach extremely high temperatures.

- Early RepRap hot-end design: This hot-end is rarely used these days because its white PTFE thermal break often fails due to jamming or to operating at too high a temperature.

FIGURE 11-15: RepRap hot-ends.

FIGURE 11-16: The J-head nozzle is now quite an old design, but it's still a great all-around choice.

Stainless steel is now the industry standard as the cold-end isolation material for hot-ends. Stainless steel can withstand much higher temperatures than PEEK and PTFE, so it can extrude thermoplastic materials with melting points higher than 250 ° C, such as polycarbonate (used in bulletproof glass). Even PEEK can be extruded, allowing you to print the cold-end insulator for another hot-end.

Advanced hot-end designs and interchangeable nozzle sizes (see Figure 11-17), including multiple nozzles and material mixing systems, are becoming more popular and reliable. The following designs will become common as more complex desktop 3D printers are developed:

E3D Cyclops: This nozzle is designed to accept two separate material feeds and allow rapid switching between them. Because it has a single output nozzle, you need to be concerned about only one point of extrusion. The nozzle does have one small disadvantage: During switching from one material to the other, a small amount of mixing occurs. If you’re using red plastic on one side and yellow on the other, for example, you see a section of orange as you switch from one to the other.

This problem is usually solved by using a material dump location (outside of the normal print area) so the nozzle can purge out (clean) a material or color so that another color or different material is not contaminated by the previous one used. Another method is to use a prime pillar that produces a useless mixed color or material pillar by printing out the remaining mixed material until the new material flow is clean or has fully changed color.

One further limitation of this nozzle is that both materials need to have compatible temperatures to function together in a single heating system. You couldn’t, for example, use PLA on one side and ABS on the other.

- E3D Chimera: This dual-nozzle and dual-heating system allows for a wider choice of dissimilar materials, which can have different temperatures and extrusion profiles. You can also use two different sizes of nozzles, which can be useful if you want to speed the infill by using a large nozzle hole while keeping the outline high-quality by using a smaller nozzle. The main disadvantage of a dual-nozzle system is that you need to carefully calibrate and align the two nozzles so that the extrusions line up. Also, the inactive nozzle may ooze plastic or accidentally knock into a previously printed feature, causing misalignment.

- E3D Volcano: The Volcano hot-end allows a high deposition rate of plastic flow so that parts can be built quickly, often with an increased nozzle size (around 0.6mm to 1.2mm, compared with the standard 0.4mm). The main drawback of the Volcano is a tendency to ooze plastic, as you have a reservoir of ready-melted plastic at any time. This drawback can be balanced by faster printing and increased extruder retraction. This design is excellent for printing large parts in which fine details aren’t critical and print time is important.

- E3D Hemera: The Hemera kit is a combined extruder feeder, cold-end-and-hot-end all-in-one, all metal, extrusion system. It still uses the industry standard V6 nozzles and has a high performance of thermal melt capabilities, making it suitable for upgrading many lower quality desktop 3D printers. (See Figure 11-18.)

FIGURE 11-17: Specialist and multiple-nozzle RepRap hot-ends: Cyclops (left), Chimera (middle), and Volcano (right).

Hot-end and nozzle design is a lively area of 3D-printer development, from tiny-geometry nozzle apertures to specialist materials that reduce wear and improve performance. It is a significant design trend well worth keeping tabs on.

The most common type of nozzle is the E3D V6, which has a standard range of nozzles in brass, hardened steel, and stainless steel to choose from. Starting at 0.15mm and going up to 1.2mm, these industry standard nozzles are now common in most types of desktop 3D printers. (See Figure 11-19.)

Alternative V6 design nozzles are also available. Some focus on being higher flow or even come with a ruby for the nozzle face to help reduce the wear on the nozzle aperture.

FIGURE 11-18: The E3D Hemera all metal extrusion system with integrated cold block and hot-end nozzle.

FIGURE 11-19: A range of V6 nozzles in different diameters from 0.2mm to 1.0mm and in brass, stainless steel, and hardened steel.

Build plates

The build plate of your 3D printer can be made from various materials. Because many 3D printers move the build plate backward and forward on the Y axis, it’s desirable to make the build plate and any heating elements as lightweight as possible so that the Y axis can move and accelerate quickly.

The build plate is normally a flat surface of sprung steel, glass, or aluminum, often with a printed circuit board (PCB) underneath. The PCB acts as a heating element when powered by the 3D printer’s electronics. Also required are thermal insulation and a way to level the build plate mechanically. With a heated build plate, you can print with a wider range of materials, but heating the build plate adds a level of complexity to the printing process and the electronics require a much more powerful power supply.

Instead of printing objects directly to the heating PCB, you need to have a smooth surface to print to, such as a sheet of glass. PLA, for example, sticks to clean glass when heated to 60 ° C and pops off the glass when it cools.

If you’re not using a heated surface with PLA, one of the best materials to use is 3M Blue Painter’s Tape for Multi-Surfaces (part number 2090). Covering the printing area with this tape allows many prints to be completed before you have to cover the build plate with new tape. The surface finish of the side touching the tape takes on the mottled appearance of the tape, however.

ABS has the opposite problem: It can have trouble sticking to the build plate. For successful ABS printing, heat the surface to 100 ° C. In addition, you have to add a layer (usually, Kapton or PET tape) to the heated glass plate to control how the ABS object sticks to the build plate. If you still have problems getting your ABS parts to stick, painting a thinned solution of ABS and acetone on the extra layer (glass, Kapton, or PET) adds bonding strength.

Finding good materials for the print surface is an ongoing quest in home 3D printing. So far, the best material for a 3D printer’s build platform is a sheet of PEI (polyethylenimine) stuck to high-temperature borosilicate glass or the PCB heater plate. This build platform is the costliest type and must be replaced after several hundred models have been printed. No other single surface has been found to be suitable for all thermoplastic filaments. Thus, as a lower-cost alternative, many users opt to fix the glass plate to the PCB heater plate with office binder clips. This method allows quick removal of build-plate surfaces and exchange with other materials if necessary.

Control interface electronics

The electronics of your 3D printer are likely to be based on the open-source Arduino platform or a common ARM 32-bit device like the STM32. Rapid advances in low-cost control electronics have started to filter into use with 3D printers, including the use of color displays, 32-bit processors, wireless control and connection to networks, and web-based control and monitoring of print jobs. (I discuss various RepRap electronics, including their modular parts and connections, in greater detail in Chapter 13.)

Software

Another critical part of 3D printing is the software used to design, output (or convert), repair, and then process 3D models into code that the printer understands.

In Chapter 15, I give an overview of the software required for producing 3D objects and explore the software used to process and manipulate 3D models for your RepRap 3D printer. In the following sections, however, I highlight a few basic 3D-printing applications.

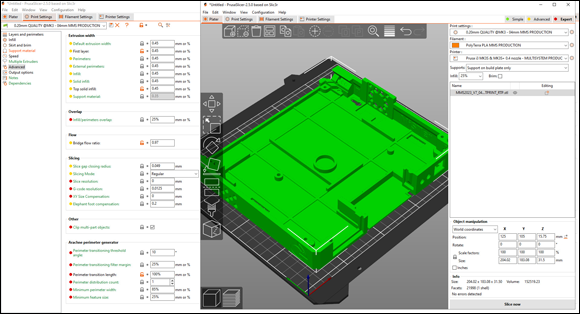

Slic3r and its successors Prusaslicer & Super Slic3r

Slic3r (see Figure 11-20), designed by Alessandro Ranellucci, is an open-source conversion tool for 3D model processing for printing. The Slic3r software is available for Windows, Mac, and Linux at http://slic3r.org. This tool formed the basis of many slicing engines available today; in fact, most 3D-printing companies have a custom version of Slic3r. (See Figure 11-21 for an example.) The capabilities are upgraded regularly, which makes it a good choice for the rapid developments in 3D printing. Check the website often to find out what’s new or improved.

The main task of any 3D print-slicing program is to slice (process) a 3D model into fine layers and plan paths for the extruder to travel as it deposits the material used on each layer. When the print-slicing program does its job correctly, the 3D printer’s firmware processes this data and controls the movement of the printer’s components to print the finished model.

FIGURE 11-20: The open-source Slic3r project homepage.

FIGURE 11-21: The open-source Prusaslicer is based on the original Slic3r project. Many settings are available for tuning every aspect of your model processing into Gcode.

The slicing program also analyzes the model for printability and then determines whether additional commands are needed — whether to print extra material to help support a bridge, for example. Further, if you elect to use support material, the slicer does its best to add the required breakaway support material automatically, so that you don’t have to change the original model. Thus, a slicing program must apply some intelligence to processing a model for 3D printing. Any overhangs of material, features, and holes that make plastic span sections of bridging may require alterations to the path of the nozzle. This can be done by changing the perimeter outlines of the object or detecting when solid layers that go in a specific direction must bridge a gap (span across back and forth) in an object to keep the print strong and appealing in its final appearance.

Cura

Cura (see Figure 11-22) is another option for processing and slicing 3D models. Cura is an open-source program developed and maintained by Ultimaker in its early days and by David Bramm, along with many members of the 3D-printing community. Custom versions of Cura are included with many 3D printers as a starting point for model processing. Like Simplify3D and Slic3r, Cura can store profiles of machines, materials, and common print configurations to make choosing easier (For more on Cura, check out https://github.com/Ultimaker/Cura.)

FIGURE 11-22: Cura slicing software.

Netfabb

Netfabb is a powerful commercial software package for many aspects of 3D file manipulation. It’s not open-source, but it has a number of older versions that are basic but still amazingly functional. You may need to search around for older free versions when Netfabb was a stand-alone company. It's now owned by Autodesk and is available to buy as a professional package.

RepRap users favor Netfabb Basic for checking model files before sending them to the slicing program. Netfabb allows you to rotate, scale, and modify (or fix) your object models. Loading a model into Netfabb before loading it into Slic3r enables you to ensure that the model looks 3D-printable, that it’s in the correct orientation, and that it prints at the size you expect and require.

Netfabb Basic is available for Windows, Mac, and Linux. A cloud-based version is available and is often even better at fixing issues with 3D model meshes that contain errors or refuse to slice correctly.

Professional versions along with specific packages of Netfabb tailored to certain 3D printers are available for purchase.

Pronterface & Printrun

Pronterface is an open-source RepRap user interface for controlling your 3D printer and sending Gcode files off to print. The complete Printrun package of software was developed by Kliment Yanev and is widely used in the RepRap home 3D-printing community.

The Printrun package is available for Windows, Mac, and Linux at http://koti.kapsi.fi/~kliment/printrun.

Pronterface is an essential program for easy use of your 3D printer. In Chapter 15, I show you how to use Pronterface to control, set up, and calibrate a 3D printer, so it’s well worth downloading in preparation.

Repetier-Host

Repetier-Host is a free alternative to Pronterface that provides a control panel for your 3D printer. It can also be linked to Slic3r.

Repetier-Host is available for Windows, Mac, and Linux, and can be downloaded at https://www.repetier.com/downloads.

ReplicatorG

Admittedly, ReplicatorG is now quite old, but it is still a well-established open-source package for both model slicing and 3D printer control. It’s widely used by some closed-source manufacturers of 3D printers but did not attain wide popularity among RepRap users and developers.

ReplicatorG is available for Windows, Mac, and Linux at http://replicat.org.

Safety first. With any type of 3D printing, health and safety is vitally important, but when you're running a 3D print farm, the importance of safety and good working practice is many times more critical. I can't continue to stress enough how important it is that you consider safe work practices. That means keeping the rooms where 3D printers are being used well-ventilated and making sure you have both smoke and fire detection in place. Most importantly, never leave 3D printers unattended when they are on or running.

Safety first. With any type of 3D printing, health and safety is vitally important, but when you're running a 3D print farm, the importance of safety and good working practice is many times more critical. I can't continue to stress enough how important it is that you consider safe work practices. That means keeping the rooms where 3D printers are being used well-ventilated and making sure you have both smoke and fire detection in place. Most importantly, never leave 3D printers unattended when they are on or running. In the early days of home 3D printing, standard spools of 3mm plastic welding wire were used. Today, plastic extrusion companies all over the world manufacture dedicated filament for the 3D-printing industry in two standard sizes of 1.75mm and 2.85mm with a tight tolerance (+/–0.1mm diameter), and true concentricity of the filament ensures high-quality printed parts.

In the early days of home 3D printing, standard spools of 3mm plastic welding wire were used. Today, plastic extrusion companies all over the world manufacture dedicated filament for the 3D-printing industry in two standard sizes of 1.75mm and 2.85mm with a tight tolerance (+/–0.1mm diameter), and true concentricity of the filament ensures high-quality printed parts.