1

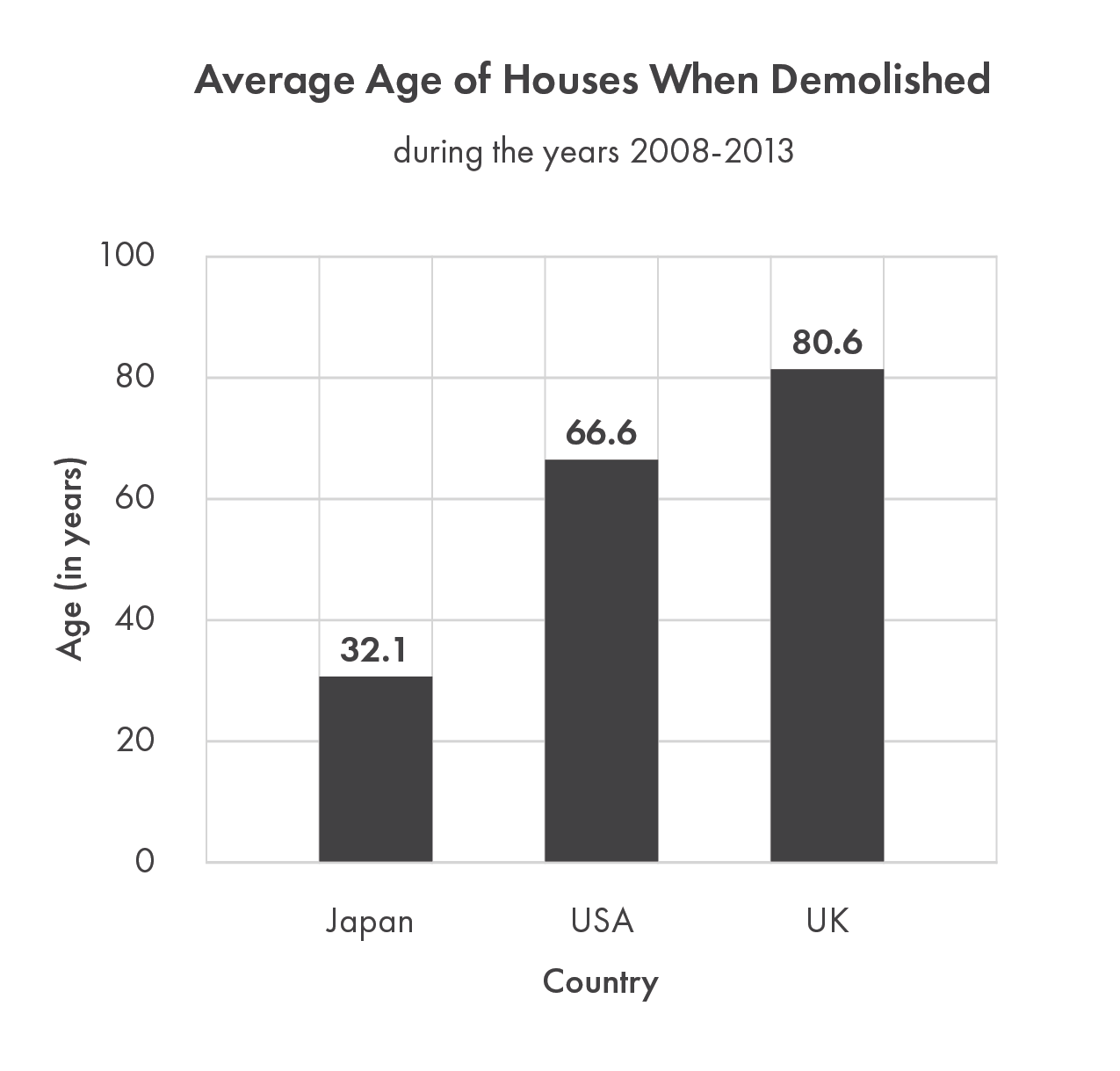

There are over 8.5 million abandoned homes in Japan,and the average age of a home when it is torn down is only 32.1 years.

When I first laid eyes on my “Tree House” apartment near Shibuya, I knew it was the one. The building’s perfect location on the top floor with big, bright windows in three directions created a fantastic atmosphere. Plus, the small ladder leading up to the loft added a unique charm. There were a couple of downsides, however. No elevator, and the building, by Japanese standards, was quite old.

The apartment was 39 m2 ( 420 ft2 ) in size and the price was around ¥14 million ( $96,552 ).* I couldn’t believe how cheap it was. In Stockholm, Sweden, I couldn’t even buy a parking lot for that money, and here I was, in the heart of Tokyo, just a quick bike ride away from the famous Shibuya Crossing ( 渋谷スクランブル交差点 ).

Japanese real estate pamphlets often lack interior pictures, leaving you in suspense until you visit the property in person. The moment I stepped inside, I could tell that the place needed some serious renovation. The small kitchen at the entrance smelled bad, and it seemed like no maintenance had been done in ages. But I was undeterred; the limiting factors could be fixed with an easy renovation.

When I showed pictures and videos of the apartment to my foreign friends from America and Europe, they couldn’t believe what a great deal it was. “ONLY 100K?! YOU HAVE TO GET IT! GET IT NOW!”

But when I showed the same to my Japanese friends, they looked at me with concern and caution. “It’s pretty old, huh? Are you sure about this? Will they clean the place before you get the keys?” they asked, more risk-averse than my foreign friends.

On the second visit, I brought my Korean girlfriend along to share in my excitement.

When we arrived outside the building, I could already tell this wasn’t going to go well. Her face looked like she had just sucked on a lemon and smelled something bad at the same time. At the entrance to the apartment she took one look inside and asked the broker why it was so dirty.

“Are they going to clean the place before we get the keys?” she asked.

I thought she was being incredibly rude. “We can fix it ourselves,” I said, adding, “your energy is really bad.”

She shot back, “It’s dirty, it’s old and I don’t want to be associated with this.”

She refused to come in, her legs and arms compressed together to keep the dirty apartment from touching her. It was like I had taken her to the slimiest, sleaziest, scuzziest trailer park you could imagine and said, “Look, babe, this is our new home, isn’t it great?” and she responded, “Are you insane? I will never, ever bring any friends here. I will never bring my family here. No one will ever, ever, EVER know that I live here.”

I told her to go wait outside while I looked at the apartment again. This place was gold covered in trash. How can she not see this?

Meanwhile (I now know) she was thinking, “This is going to destroy my reputation, how can he not see this?”

What’s funny is, since then we’ve had bigger fights over smaller things. She didn’t like it, but at some level she knew that I had a vision, that this was my choice, and this was something I had to do. As big of a life-changing decision as this was—buying an apartment after only living in the country for a few months—she supported me in doing it. She didn’t help at first, and she definitely didn’t understand it, but she didn’t try to change my mind.

I made the purchase and we moved in together to her 20 m2 ( 215 ft2 ) apartment in order to save money. She helped a little with the initial clean up, but then the very dirty demo work began and I was on my own. On the days I wasn’t modeling I would return to our shared and very small apartment completely filthy. Can you imagine how excited she was?

But when we started to paint and decorate, she started to get involved. When she saw the apartment coming together so beautifully, she was blown away. She hadn’t realized that you could do these things—that they were even possible. Now she’s as excited as I am to look at old, dirty houses. We’re a team. She sees it, understands it, and has the vision. Now when I take her to a dirty, abandoned old house, she’s like: “Let’s DO IT!”

Now that I’ve spent more time in Japan, I also understand better why she had that less-than-positive reaction to the Tree House apartment. The Japanese have very different feelings and beliefs about older homes than people in the United States and Europe.

Tokyo has limited space and the way Japanese people live and spend their lives is very different from anywhere else. Japanese architecture is beautiful and renowned all over the world, and I love looking at these old, beautiful Japanese kominkas ( 古民家 ) and temples. Simply a work of art. But what do Japanese people prioritize in their homes?

I have seen and been to a vast amount of Japanese houses, apartments, and condos—what the Japanese call manshons ( マンション )—mostly in and around Tokyo: small windows, nearby buildings blocking the sunlight, big fluorescent panel lights in the ceiling, walls covered in the same trending white wallpaper, vinyl flooring, unit bathroom, unit kitchen. Everything made to look as fresh and new as possible. Get a gouge in the floor? Have the entire floor redone in a day. Need a new kitchen? Out with the old unit kitchen and in with the latest one. Takes the contractor a day or two. The apartment is easy to maintain and it looks nice, but most importantly to a Japanese buyer or tenant: it looks New.

Plus, this building will probably be torn down in 25–30 years, so why bother making it personal?

Overview of the Situation in Japan

In Japan, the perspective on home value is quite different from many other countries. While older homes often hold historical and aesthetic value in other places, in Japan, newly-built homes are highly preferred. This perspective stems from the belief that the land itself holds greater value than the aging structure, particularly in light of new regulations addressing earthquake safety. The government has even set a fixed-term depreciation period of twenty-two years, so homes in Japan are literally worth nothing after twenty-two years.**

The trend of demolishing and rebuilding homes is also deeply rooted in Japan’s history, influenced by post-World War II construction techniques and updated building codes to withstand earthquakes and natural disasters. People expect the house to lose value quickly, resulting in little motivation to maintain them for potential future buyers. As a result, the country has a large number of registered architects due to the constant demand for custom-built homes.

So what contributes to this cultural norm of always rebuilding new homes? Fires, earthquakes and a housing bubble that burst.

Fires

Throughout its history, Tokyo has been no stranger to devastating fires. From the early days of Edo to the modern city of Tokyo, fires have posed a constant threat. The city’s dense layout, with houses situated close to each other, has made fires particularly rampant and destructive.

One of the most significant fires in Tokyo’s history was the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657, which engulfed the city and resulted in the loss of over 100,000 lives. The Great Kantō Earthquake in 1923, which triggered massive fires, wiped out entire neighborhoods. The fire-bombing of Tokyo during World War II destroyed 16 square miles ( 41 km2 ) of the city and left over a million people homeless. Each time, the city was rebuilt.

The memory of past fires remains a cautionary reminder for Japanese people. They have adopted a strong cultural awareness of fire safety. Even today, the rhythmic sound of striking wooden batons and the chant of hinoyoujin ( 火の用心 ), beware of house fires, echoes on summer evenings. As Tokyo has embraced modernization, fire safety became a primary concern. Many house builders and developers now prioritize fire safety as a main selling point. Advanced technologies, improved construction materials, and strict building codes have been implemented to minimize the risk of fires spreading rapidly.

Earthquakes

Japan is a country of earthquakes, and while we feel the trembling from time to time, I must admit, earthquakes are scary. I didn’t experience the big earthquake in 2011, but I remember it vividly, reading the news in my mother’s house in the suburbs of Stockholm. Years later, I visited Fukushima for a week-long photo shoot. Talking to people affected in MinamiSoma, Fukushima, really made me realize the seriousness of earthquakes and tsunamis. I would strongly recommend people who don’t believe in the power of nature to search on Youtube for Fukushima 2011. The videos of the tsunami sweeping in and the clips from the shaking airport will always be in my mind. My heartfelt thoughts continue to be with all the people who went missing and lost their lives in this tragedy.

There’s a 70% chance of a strong earthquake hitting Tokyo directly in the next thirty years. Researchers, led by Professor Akira Fuse from Nippon Medical School and data analysis company BrainPad, studied what could happen if people don’t get medical help after such a quake. Using past data and government estimates, they found that in a severe situation, around 21,500 people could be badly hurt if an earthquake happens north of Tokyo Bay. Among these, about 6,638 people, or around 31%, might not be able to get the care they need and could die. Most of these unfortunate cases would likely be in areas with many wooden buildings. About 90% of these potential deaths might occur in parts of Tokyo’s northeastern and eastern wards.***

Big earthquakes and evolving building techniques are the reasons why laws within building in Japan are changing. Most old buildings, especially the ones built before 1981 are not up-to-date with the latest building requirements for earthquakes and fire protection. Earthquake retrofitting has been a necessary project on all of the homes I have renovated in Japan.

Housing Bubble

During the 1980s, Japan experienced a financial and economic boom, famously known as the “Bubble Era.” The period saw unprecedented growth in real estate prices, transforming Tokyo’s skyline with towering skyscrapers and luxury properties. Much like the US housing bubble in 2008 that fueled the Great Recession, Japan’s Bubble Era was characterized by a rapid surge in asset prices, including real estate. Land prices, particularly in Tokyo and other major cities, skyrocketed to astronomical levels. The insatiable demand for prime properties and the willingness of financial institutions to extend loans fueled the bubble’s expansion, mirroring the sentiment in the US housing market during the early 2000s.

However, the Japanese housing bubble burst in the early 1990s. Speculation and excessive lending practices reached a tipping point. Overnight, property prices plummeted, leaving many investors, corporations, and financial institutions burdened with massive debts and unsellable properties.

In the aftermath of the bursting bubble, Japan experienced its “Lost Decade,” a prolonged period of economic stagnation that shares parallels with the Great Recession’s impact on the US economy. Real estate prices suffered prolonged deflation, leading to a subdued market and sluggish demand. This aftermath continues to shape the way Japanese people perceive the real estate market in Tokyo. Decades after the bubble burst, the memories of the unprecedented rise and subsequent devastating crash have left a lasting impact on the nation’s collective psyche.

There is one abandoned home in Japan for every person in New York City!

For many Japanese citizens, the cautionary tale of the Bubble Era serves as a stark reminder of the risks associated with speculative buying and excessive lending practices. As a result, there is a prevailing sense of conservatism and prudence when it comes to real estate investments. Japanese home buyers tend to approach the market with a focus on long-term stability and practicality, rather than chasing short-lived market euphoria.

Why Are There “Free” Houses in Japan?

There are an estimated 8.5 million abandoned houses (akiyas) across Japan, and around 810,000 of those are in Tokyo.**** For comparison, in 2021 the population of the five boroughs of New York City was 8.4 million people. The ward I live in, Setegaya—the Brooklyn of Tokyo—has nearly 50,000 abandoned homes, the highest number of any ward in Tokyo.*****

Why are there so many “free” homes in Japan? (They are not really free, as many claim, but they are very, very inexpensive.) Why can you find so many inexpensive abandoned houses in Japan? Deflation, depreciation, and a declining population are three key factors.

Deflation

Japan is the third-largest economy in the world, also measured in real estate value, and it boasts a rich history of innovation and prosperity. However, the past few decades have seen the nation grapple with prolonged economic stagnation and deflationary pressures. Now often referred to as the “Lost Decades,” Japan’s economic growth has been relatively subdued compared to its rapid expansion in the post-war era.

While in the last couple of years Japan has been experiencing low inflation, one of the defining characteristics of Japan’s economy has been its persistent struggle with deflation. Unlike the United States, where inflation is a normal occurrence, Japan has faced prolonged periods of falling prices. Deflation has a detrimental impact on consumer spending and business investment, leading to a vicious cycle of reduced demand and sluggish economic growth.

In an attempt to combat deflation and boost economic activity, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has pursued an ultra-accommodative monetary policy. Interest rates have been historically low for an extended period, with the BOJ adopting a near-zero or even negative interest rate policy. This has aimed to incentivize borrowing, spur investment, and increase spending. However, the effectiveness of such measures has been a subject of debate.

Since 2012 Japan has also embarked on a series of structural reforms under the banner of “Abenomics.” Named after former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, this policy framework aimed to promote economic growth through three arrows: monetary easing, fiscal stimulus, and structural reforms. While progress has been made, the country continues to face challenges in breaking free from deflationary pressures.

Depreciation

Now let’s talk about depreciation. Unlike in many countries where houses and buildings appreciate in value, in Japan, buildings are subject to depreciation for tax purposes. The concept of depreciation allows the government to gradually reduce the assessed value of a building over time, reflecting its wear and tear and decreased value due to aging. The Japanese National Tax Agency provides a depreciation table that indicates the estimated useful life of different building structures. The table specifies the number of years over which the building’s value is expected to decrease until it reaches a residual value of zero.

Here’s an example of how depreciation works:

Let’s say you own a wooden house, and the Japanese tax authorities have set the estimated useful life for wooden structures at twenty-two years. Each year, the value of your wooden house will decrease by a fixed percentage until it reaches zero after twenty-two years.

Suppose the initial value of your wooden house is ¥10,000,000 ( ~$69,000 ) excluding land. After the first year, if the depreciation rate is 5%, the assessed value for tax purposes will be ¥9,500,000 ( ¥10,000,000 - 5% of ¥10,000,000 ).

After the second year, the depreciation rate will be applied to the adjusted value of ¥9,500,000, resulting in a further decrease in value, and so on for the subsequent years until the estimated useful life of twenty-two years is reached.

The depreciation rate can vary depending on the building’s structure and type. Tax laws and regulations also might be subject to change over time, so it’s essential to consult with a tax professional or the local tax authorities for the most up-to-date and accurate information on building depreciation for tax purposes.

From my perspective, it’s important to note that all akiyas ( 空き家 ), abandoned houses, I’ve encountered in Tokyo and it’s surroundings have already reached a tax valuation of almost zero. Despite this low value, it’s essential to remember that these properties are still houses, with the potential to be something more. While the tax valuation may show zero, I believe that with thoughtful investment and creative vision, these akiyas can become attractive homes for potential buyers or tenants. The key lies in leveraging the expertise of experienced real estate professionals who can assist in navigating the complexities of property renovations in Japan.

While the value of the actual houses on the land may depreciate, the land-value in popular areas tends to appreciate over time. The appreciation of land value in Japan is partly attributed to the limited land availability, particularly in urban centers like Tokyo. There can often be a stark contrast between the increasing value of the land and the decreasing value of older houses. If you want to access the land an old house stands on, you have to tear the old house down. This means that the “free house” you got when buying the land isn’t really free. In reality it has a negative value. The overall cost of buying the property and removing the old house can be more than what the land and house are worth together.

Declining Population

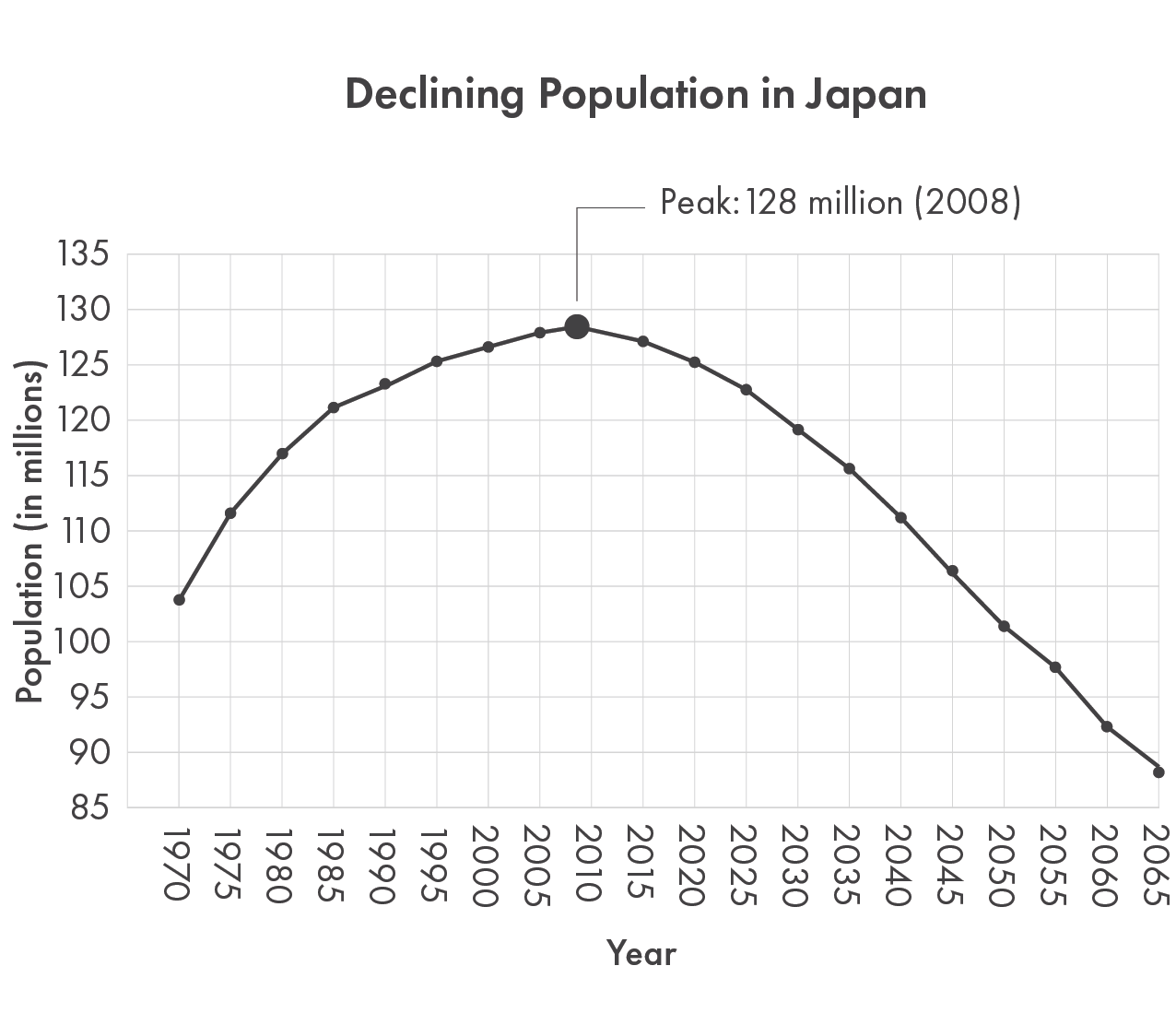

Japan’s aging population and declining birth rates also pose significant challenges to its economic growth prospects. With the fastest-aging population of any post-industrial nation on earth, Japan’s birth rate (the average number of children a woman has) started to decline in the 1970s, and in 2021 fell to 1.3. It takes a birth rate of about 2 to keep a steady population. In 2022 the population of Japan was 125.4 million people, having dropped by over a half-million people in one year. As a result, the workforce is shrinking, leading to a decrease in productivity and potential economic output. This demographic shift has far-reaching implications for various sectors, including the housing market.

Japanese Preference for New Houses

Not only are there fewer people in Japan, those people have a strong preference for newly-built properties. Japanese buyers prioritize modern amenities, advanced safety features, and the assurance of minimal maintenance. Newly-constructed properties are often considered a safer investment choice due to their lower risk of hidden defects and the potential for resale in the future.

Japanese homes are often built with a relatively shorter economic life in mind. Wooden structures are expected to be torn down in 20 years and concrete and steel buildings in 30 years. Due to the shorter expected life-span, often the building materials and techniques used in the past may not meet modern construction standards. As a result, older houses may require more frequent maintenance and renovation, further contributing to their depreciation.

Because of this, Japanese homeowners have a completely different relationship with their homes than Americans or Europeans. People aren’t thinking about resale value because the house loses value rather than gains, and thus the house isn’t maintained in order to increase its longevity. The house will have zero value eventually because of how the depreciation system works, plus it won’t have the latest earthquake technology so it’s not worth it. Because of this, the Japanese home owner just doesn’t maintain their home in the same way as a US or European buyer would. Seasonal rituals designed to extend the life of your home that you may be used to in the US or Europe such as caulking exterior cracks, cleaning gutters or removing moss are not activities that Japanese homeowners participate in. There’s simply no incentive to do so.

One of the interesting effects of this system I’ve noticed is that the rent for a brand-new house in Tokyo in some areas will be more than 40% higher than the rent for an apartment that is over thirty years old—even if they are in the same area, on the same street, or even right next to each other.

However, there are signs of a shift in this trend. Some homeowners are now exploring smaller-scale renovations, rethinking the idea of tearing down entire homes. Japan’s changing demographics, including the declining and aging population, having led to a higher number of vacant homes, has prompted a new interest in rehabilitating older houses instead of building new ones. In particular, renovated manshons, similar to what an American would consider a condominium, are becoming more trendy. Additionally, in urban areas like Tokyo, innovative housing options are emerging. Companies are transforming old office spaces into apartments and creating co-living spaces, promoting a more affordable and communal way of living. This move away from traditional housing reflects the evolving needs and preferences of younger generations.

The Treasure Trove

In the bustling heart of Tokyo, where ancient temples mingle with neon lights, lies a treasure trove. Through my journey of buying and renovating within this market, I’ve discovered countless opportunities, particularly in affordable Japanese houses. What I have found truly astonishing, especially in Tokyo, is the surprisingly low entry point. Properties that would be considered luxuries elsewhere are within reach here. Take, for instance, the Tree House apartment, which kickstarted my real estate journey. It’s a prime example of how you can own a unique piece of Tokyo without breaking the bank.

While the Tree House wasn’t technically an abandoned property, it was still priced at ¥14 million ( ~$96,500 ) for a 39 m2 ( 420 ft2 ) apartment only ten minutes from Shibuya Crossing. A new home in that same area that same size would be about ¥72.5 million ( ~$500,000 ). The Tree House was owned by a man who lived in Hiroshima. He hadn’t come to Tokyo for years and didn’t know what he wanted to do with it. There were so many old, cheap houses and he was competing to try and sell his. Many good real estate agents (called brokers in Japan) don’t want to deal with selling them because the commissions are so low on such a low-priced property. The brokers simply don’t put in much effort to sell the home. I’ll share more about the purchase of the Tree House, and dealing with brokers, later in this book. The key point here is that there is a tremendous opportunity to find and renovate inexpensive homes in Japan, just like I have done many times.

Up until now, accessing information about this market, especially for non-Japanese speakers, has been quite challenging. That’s precisely why sharing insights and experiences with a global audience is now more crucial than ever. I feel a strong sense of duty to debunk myths, demystify the complexities, and provide firsthand knowledge to an English-speaking audience. Akiya investments have become quite popular among Japanese investors in recent years, and there are already numerous books in Japanese on the subject. Here, I’m unlocking this world for the first time with an English-language book on the subject.

The intention of this book is to empower you with knowledge and ideas, not to provide specific financial recommendations. Please consult with a qualified financial professional before making any investment decisions.

I’ve heard your questions and curiosity, and I’m here to share. In this book, I’ll pass on what I’ve learned from my own experiences, both good and bad, and from those of my friends. You’ll gain a deep understanding of Tokyo’s real estate market, especially when it comes to older Japanese houses, and the opportunities that lie within this growing market. By the end, you’ll feel ready to confidently navigate this unique market.

But first, you’ll have to get to Japan.

* For consistency, we have set an exchange rate of ¥145 per $1 throughout the book, and all dollar amounts are United States dollars. As currency exchange rates vary daily, the current exchange rate at the time you are reading this book is likely different.

** “Japanese Homes Aren’t Built to Last—and That’s the Point”, Robb Report, May 8, 2021, https://robbreport.com/shelter/home-design/japanese-homes-are-ephemeral-facing-demolition-just-22-years-in-heres-why-1234608438/

*** “Tokyo risks over 6,000 ‘untreated deaths’ in major earthquake”, Nikkei Asia, March 11, 2023, https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Natural-disasters/Tokyo-risks-over-6-000-untreated-deaths-in-major-earthquake

**** “What to do with Tokyo’s hundreds of thousands of abandoned homes”, Real Estate Japan, February 15, 2018, https://resources.realestate.co.jp/news/what-to-do-with-tokyos-hundreds-of-thousands-of-abandoned-homes/

***** “Setagaya has the largest number of akiya (empty homes) in Japan”, Japan Property Central, May 12, 2020, https://japanpropertycentral.com/2020/05/setagaya-has-the-largest-number-of-akiya-empty-homes-in-japan/