4.

The Asthma Study

When I first put myself on the Alternate-Day Diet, I found, to my surprise, that within just two weeks the arthritis I’d had in my shoulder for more than five years improved tremendously. I was so pleased with the results that I told a good friend of mine what I’d been doing. Lenny, a fifty-seven-year-old trial lawyer, was naturally a skeptical guy, but he decided to try it himself. For some time, he’d been plagued by a painful heel spur that, according to his orthopedist, would only be helped by surgery, and, much as Lenny loved a good challenge, that option wasn’t one he wanted to accept. Shortly after starting the diet, he took his family on a ski vacation in Sun Valley, Idaho. On their first day there he tried to hike up a 6,000-foot mountain with his kids but had to stop after 200 feet because of the intense pain in his foot. Ten days later, on the last day of their vacation, he hiked the entire mountain with no pain at all. Lenny was convinced. He continued to follow the diet, eventually lost 25 pounds, and is still following his own modified version of the Alternate-Day plan. He’s kept the weight off and hasn’t had any recurrence of the problem with his heel.

My own outcome and Lenny’s—particularly in terms of the rapidity with which they occurred—were fascinating to me, and I started to put some of my patients on the diet. Marla was the classic example of a woman with a lovely face hidden in layers of fat. She came to see me about a cosmetic procedure that, as I explained to her, I couldn’t perform because I was afraid that her weight would put her at serious risk. She was 5 feet, 4 inches tall and weighed 213 pounds. Coincidentally, she was also using three different types of inhaled bronchodilators for asthma twice a day. She wasn’t in denial about her problem, just incredibly frustrated by her past attempts to lose weight, and she asked me what kind of diet I’d recommend. When I told her about the Alternate-Day Diet and its apparent health benefits, she was more than willing to try it. Before she began, we drew blood to measure her insulin and serum lipid levels and determined that she would use 400 calories in the form of a commercial meal-replacement shake to control her calorie intake on the down day.

After three weeks on the diet, Marla was using her inhalers only once a day, and after six weeks she was off them entirely. I, along with Marla and her pulmonologist, was amazed. Although she did lose weight—she was down to 198 pounds after six weeks—the weight loss alone wasn’t significant enough to account for such a drastic pulmonary improvement.

In addition, her insulin levels were initially so high that she was at very high risk for developing diabetes. I tested her insulin level at two, four, six, and eight weeks. It remained at 30 micro units per milliliter of blood serum through six weeks, and then at eight weeks it suddenly dropped to 10 and continued to decrease over the next four months from 10 to 8 to 3 to 1 micro unit per milliliter, even though her weight had stabilized at 178 pounds. What’s particularly interesting about these findings is that even though Marla was still overweight, her insulin levels continued to improve.

After a while, Marla admitted to me that while she was still on the diet, she was eating closer to 30 or 35 percent than 20 percent of her normal calorie requirement on the down days as well as more than she had been during her first few weeks on the diet on the up days. So even this less restrictive approach to Alternate-Day dieting was sufficient to continue improving her insulin response—an outcome that replicated Mattson’s findings, in which insulin levels decreased the most in the mice who were fed on alternate days even though they didn’t lose weight.

After eight months Marla called me one evening in the throes of a severe asthma attack. When I asked what had happened, she confessed that she’d gone off the diet three weeks before because she wanted to see if it really was curing her asthma. I guess she was convinced, because she went back on the diet and had the same improvement she experienced the first time.

WOULD IT WORK FOR OTHERS AS WELL?

Along with my own experience and that of my friend, Marla’s improvement seemed to indicate a high degree of anti-inflammatory benefit from following a diet based on alternate-day calorie restriction. At that point, I was eager to test for myself, under controlled circumstances, whether it was a feasible method of dietary restriction that could improve the lives of a specific population with observable health issues.

To do that, my colleagues and I recruited a single group of ten overweight people who had stable, moderate, persistent asthma with daily symptoms. Our goal was to determine whether they would adhere to a diet providing 20 percent or less of their normal calorie intake on alternate days, and whether the diet would affect their weight and/or the severity of their symptoms.

There were three reasons for choosing asthma patients in particular: Asthma is an illness associated with inflammation, and we wanted to determine whether the expected anti-inflammatory effects of the diet would affect the severity of their symptoms as they apparently had Marla’s. Second, asthma symptoms are observable, vary from day to day, and are easy to monitor. And third, asthma had been linked to obesity even though weight loss alone had not been shown to improve symptoms.

Working with Warren Summer, chairman of the Pulmonary Medicine section at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, we designed a protocol for measuring asthma symptoms, and developed an eight-week study plan.

After establishing baseline values for asthma symptoms, weight, serum lipids, glucose, insulin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (both indicators of inflammation), leptin and ketone levels, and levels of other chemicals, the study subjects were placed on a diet that—based on the average caloric requirement of 1,900 for men and 1,600 for women of normal weight—allowed the women to consume 320 calories and the men 380 calories (approximately 20 percent of normal) in the form of a canned meal-replacement shake on alternate days. On the days they weren’t restricting, they were instructed to eat normally until they felt satisfied but not to intentionally overeat.

They were also given three questionnaires to fill out. The Asthma Symptom Utility Index Questionnaire, which is a tool for comparing the severity of symptoms among various individuals, was completed at the start of the study and every two weeks thereafter. Both the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, in which patients assessed their perceived quality of life with relation to various issues, and the Asthma Control Questionnaire, which asked questions about the frequency and severity of various symptoms, were completed at the start and again at the end of the study.

THE QUESTION OF COMPLIANCE

Starting out, we were curious to know whether or not our study subjects would comply with the diet. In the end, we considered only one person a noncompleter because she admitted that she was eating on the down day, which meant we had achieved 90 percent compliance.

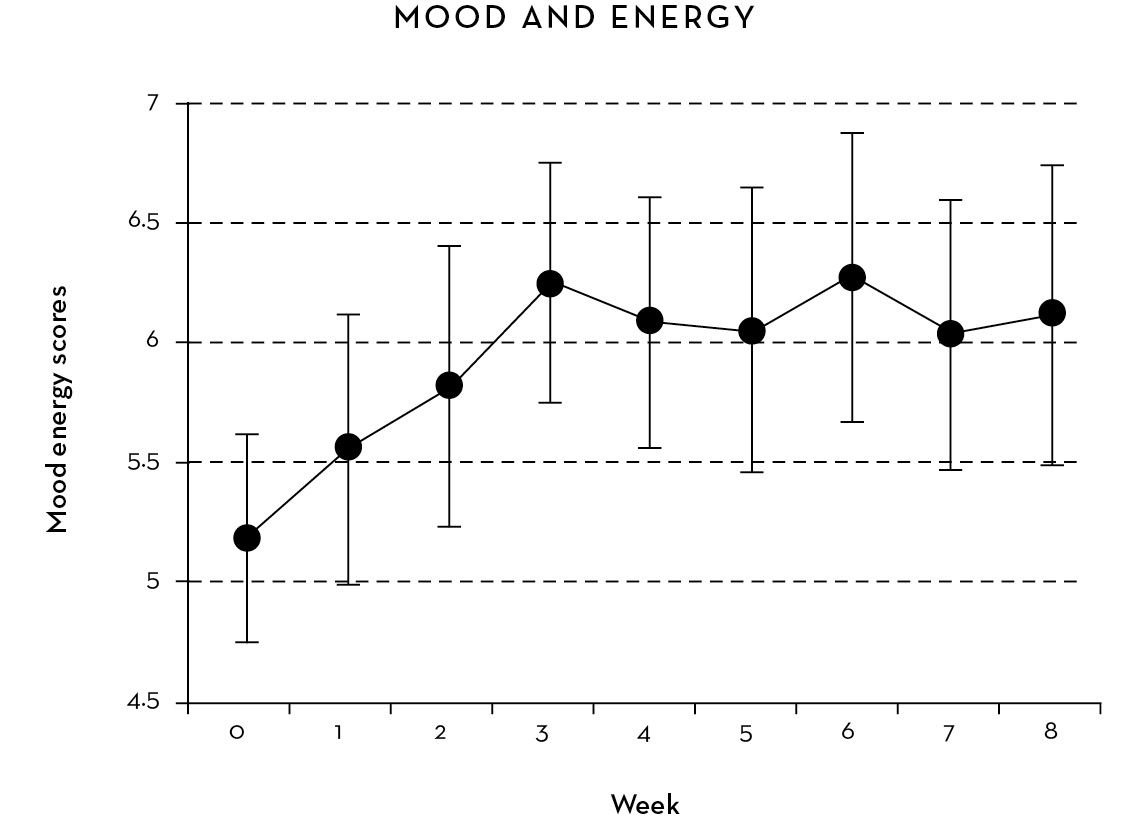

And apparently our subjects did not consider the regimen to be too onerous, because the self-assessed mood and energy levels of those who completed the study increased progressively during the first three weeks and remained elevated to the end.

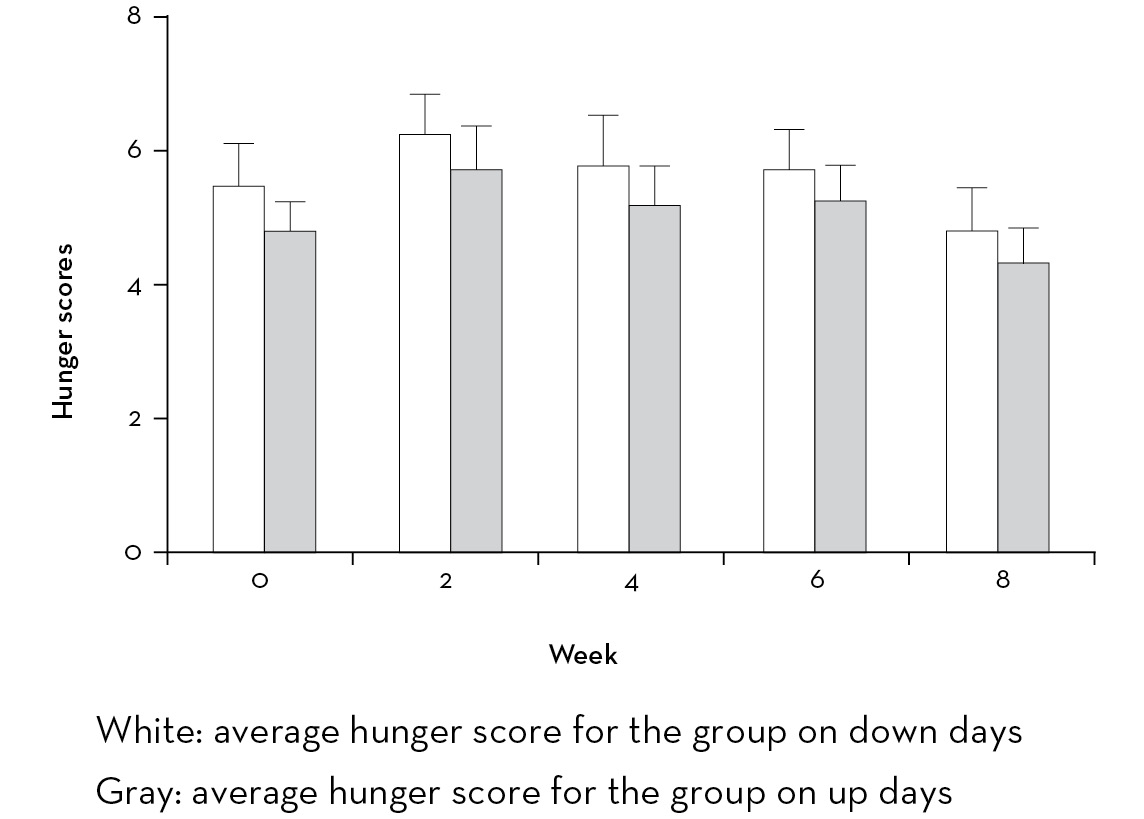

They recorded their hunger levels every two hours while they were awake, and they did score hunger levels higher on the down day than on the up day. But the difference, on average, was only 0.4 on a scale of 1 to 10. And they were no hungrier on the up-days than they had been during the run-up period when they recorded feelings of hunger in order for us to arrive at a baseline level. Nor did they report feeling hungrier as the study progressed. In fact, both overall hunger and the difference between up and down days declined over time. Their self-reports confirmed my own anecdotal impression that hunger on the down day was not so excessive as to prevent compliance.

ASTHMA SYMPTOMS IMPROVED RAPIDLY

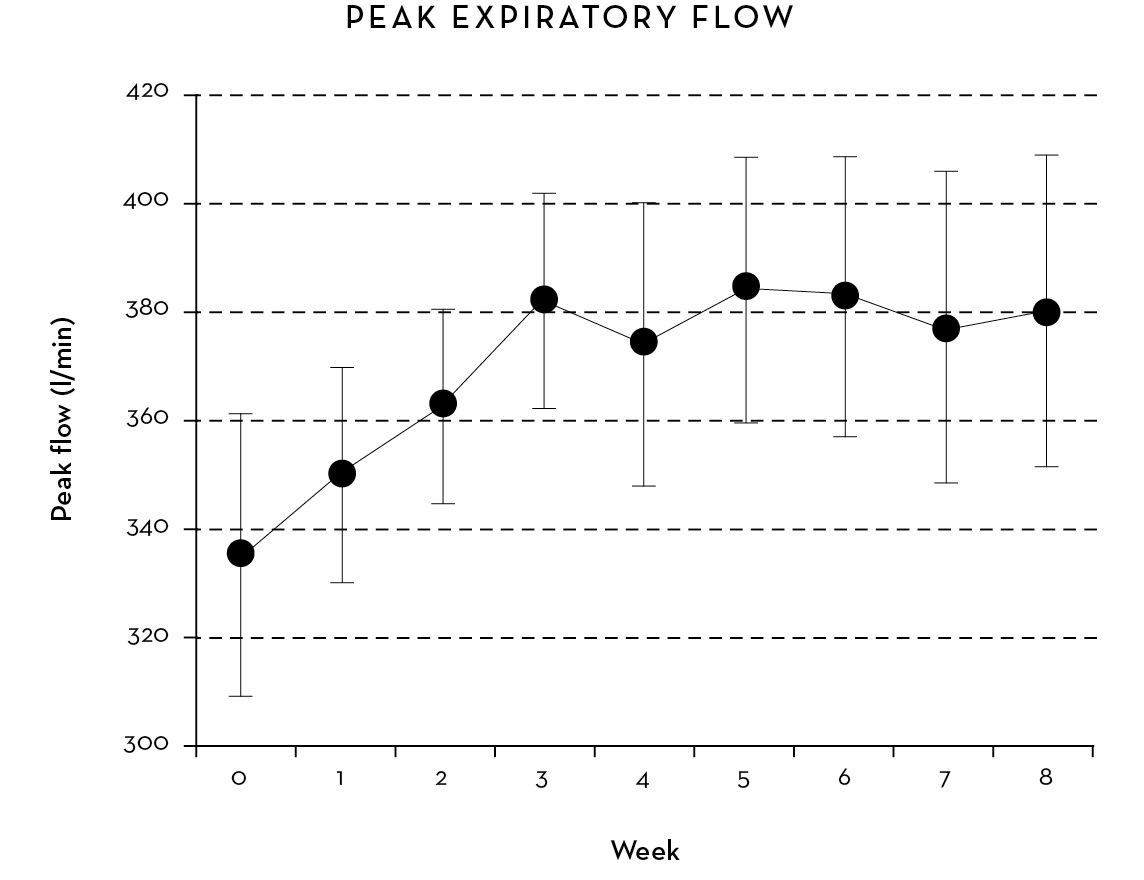

One measurement of the severity of asthma symptoms is peak expiratory flow (PEF, or the amount of air a subject is able to blow out in a single breath). In our subjects the PEF showed a highly significant increase (more than 14 percent) beginning within three to four days of starting the diet, reached a peak at three weeks, and remained elevated for the duration (see chart). A second tool is to compare and measure the improvement in FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in one second) before and after administering a bronchodilator. This too was significantly improved by the end of the eight weeks.

SELF-ASSESSED HUNGER DURING THE ASTHMA STUDY

Beyond these measurable results, however, our study participants showed highly significant improvement on the Asthma Symptom Utility Index, the Asthma Control Questionnaire, and the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire starting within two weeks and lasting throughout the eight-week period. In fact, quality-of-life issues were significantly improved for all four indicators—asthma symptoms, activity limitations, emotional function, and environmental stimuli—at the end of the study as compared with those reported at the beginning. Improvement in mood and energy scores as recorded by the participants (see chart) was highly correlated with improvement in Peak Expiratory Flow.

There may have been a global mood improvement because the subjects were breathing better, but there also appears to be something about this diet that generates a euphoric or energized state of mind.

People following the Alternate-Day Diet universally experience an increase in energy after just a few down days. While mood and energy also improved on the up days, there appears to be a greater change on the down days. Other studies of short-term fasting have shown an increase in circulating norepinephrine and cortisol levels. The improved mood may be mediated through an increase in the brain in the concentration of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which acts to increase antidepressant action in the human brain and is known to increase in the brains of alternate-day-fed animals. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is present in the peripheral bloodstream and actually is correlated with inflammation in the peripheral tissues, as opposed to the brain itself, where levels rise in response to alternate-day feeding.

By week 3 all the participants were in a “wired” state—they were talking more and were more energized—a change that is consistent with the increased brain function and activity levels found in studies restricting the calorie intake of both rodents and monkeys. Not only have these animals been shown to become more active, they have also become, in effect, “smarter.”

Studies have shown that both calorie restriction and alternate-day feeding improve memory in rodents, and, as we have seen, alternate-day feeding has also been shown to improve resistance to experimental brain injury such as injection of a toxin into the hippocampus. This is important because the human brain is constantly being subjected to injury from metabolic insults and oxidative stress. So by extrapolation, the Alternate-Day Diet could also be expected to mitigate brain injury and preserve brain function.

REDUCTION IN OXIDATIVE STRESS

Elevated levels of nitrotyrosine in the blood is a research tool commonly used as an indicator of oxidative stress. It is elevated in people with heart disease and has been shown to be a hundred times more sensitive as an indicator of impending heart attack than the standard risk factors—cholesterol, blood pressure, and so on. The chart on the next page shows a 90 percent decline in nitrotyrosine levels over an eight-week period among participants in the Asthma Study. The samples were obtained fasting in the morning on two consecutive days after an up day (light-colored bars), and then after a down day (dark-colored bars) on study days 1 and 2, 15 and 16, 29 and 30, and 57 and 58.

Note that:

• Most of the decline occurred by day 30.

• There is a significant reduction in nitrotyrosine after a single down day, especially comparing days 1 and 2, 15 and 16, and 29 and 30.

• Every subject had very low and very similar levels at the end of the study (very short standard error bars).

• The decline in nitrotyrosine level that occurs after a single down day (especially between days 1 and 2 and 15 and 16) means that these declines occurred without weight loss. If the subjects had eaten enough on the following up day to not lose weight, they still would have shown these declines. For this reason, we believe the alternate-day pattern works in the absence of weight loss.

• In contrast, in Mattson’s study of subjects eating one meal a day there was no change in markers of oxidative stress and inflammation.* The difference in the outcomes between these studies suggests that a period of about 36 hours is more effective than a period of 20 hours in activating the SIRT1-mediated CR mechanism.

THE ANTI-INFLAMMATORY EFFECT

Oxidative damage and inflammation on the cellular level appear to be highly correlated in a complex cause-and-effect relationship. Oxidative damage is both a cause and a result of inflammation. But what exactly is inflammation? If you have a skin infection you’ll see it manifested as redness, swelling, tenderness, and increased heat at the site of the infection. But these same changes can also occur in the walls of the arteries and, in the case of asthma, the lining of the small airways in the lung. The inflammation causes the lining to swell and the smooth muscle in the airways to narrow, which, in turn, causes wheezing and difficulty breathing. In fact, the main treatment for asthma is the use of an inhaled corticosteroid spray that suppresses the inflammation.

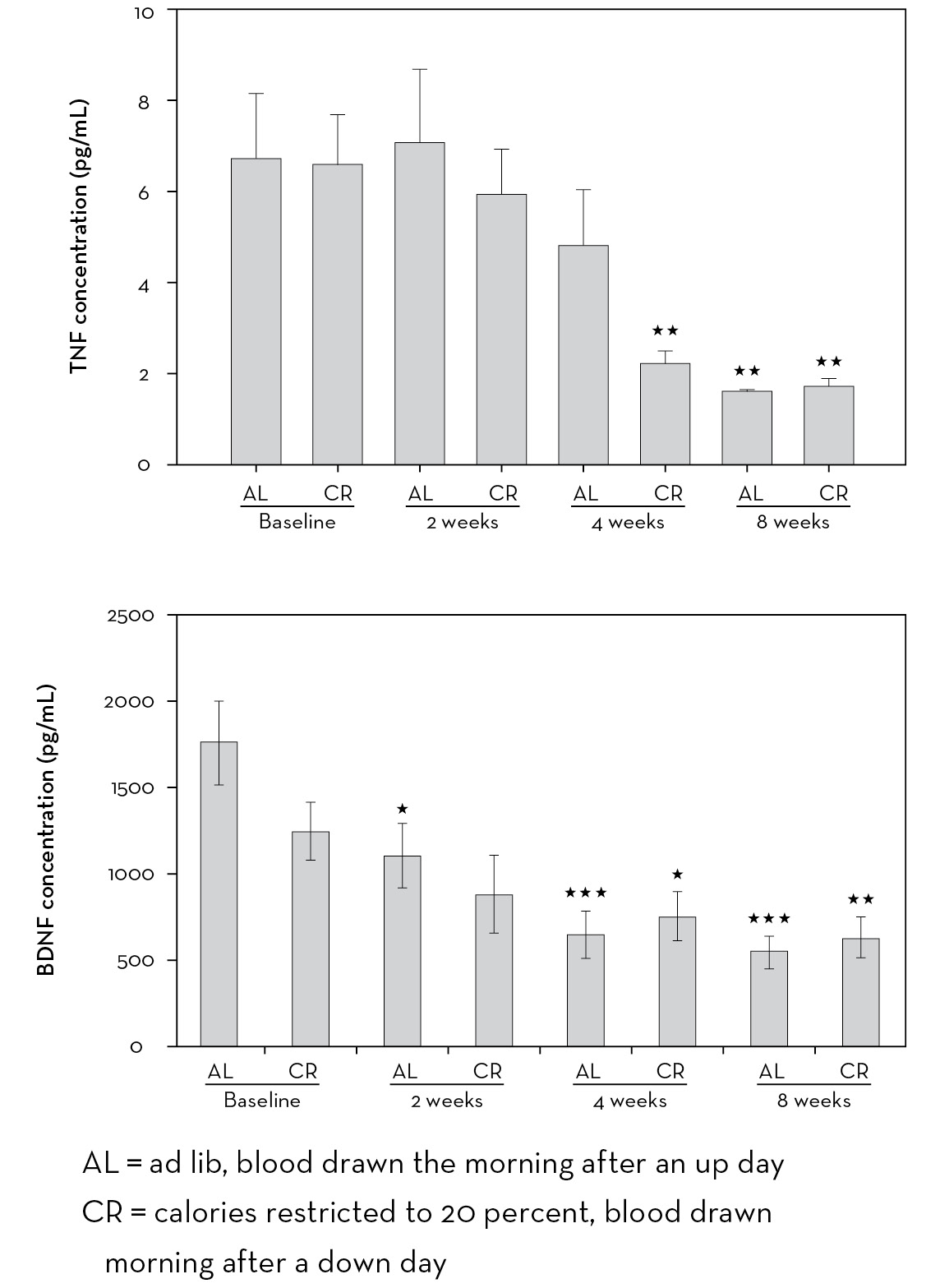

The alleviation of symptoms in patients in our Asthma Study would, in itself, have been an indication that they were experiencing a reduction in inflammation, but we also measured specific chemical substances in the bloodstream that are known to be indicators of inflammation. Over the course of the study, their levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, which is the most commonly used measure of inflammation, were reduced by two-thirds. Levels of TNF-alpha generally decline in association with weight loss, but the degree of reduction experienced by the people in our study was much greater than that reported in any study of weight loss we were able to find.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), whose presence in peripheral circulation also indicates the presence of inflammation, declined 70 percent as well. We had to conclude from these results that the reduced energy supply (reduced calorie intake) on the down days was activating a powerful anti-inflammatory mechanism that increased progressively over a four-to-eight-week period.

In addition, levels of uric acid, a natural antioxidant, were increased, indicating an improvement in the body’s antioxidant response. And levels of leptin—a pro-inflammatory substance that is, interestingly, also an indicator of hunger—decreased.

No other documented dietary or nondrug intervention has ever shown such a marked change in the levels of inflammation, meaning, we believe, that the Alternate-Day Diet has a potent effect on what is believed to be one of the main causes of a number of chronic and life-threatening illnesses, including arthritis and atherosclerosis.

OTHER SIGNIFICANT FINDINGS

Our study subjects did lose weight—about 8 percent of their initial body weight on average. Their levels of serum butyrate (an organic compound called a ketone) increased on down days, indicating compliance with the down-day dietary restriction and a shift in metabolism toward utilization of fatty acids—meaning that more fat was being used for energy instead of being stored.

A final positive finding was that their levels of HDL (good) cholesterol increased, creating a much more favorable ratio of good to bad (LDL) cholesterol, even though LDL levels themselves did not decrease significantly. Their ratios of triglycerides to HDL also changed significantly, indicating a significant decrease in insulin resistance even though the reduction in insulin levels themselves did not reach statistical significance. This finding alone suggests that the Alternate-Day eating pattern might be a way to treat prediabetics who don’t require hypoglycemic agents or insulin.

Is It Ever Too Late?

Marla’s experience as well as that of the Vallejo study subjects points out two related facts about calorie restriction: first, that it is never too late to start a program, and second, that there is an almost immediate onset of the positive effects that prolong survival. The average age of the Vallejo subjects at the start of the study was probably about seventy. Yet the diet clearly prolonged their lives.

We cannot measure long-term human survival because of the length of our lifespan, but we can measure effects of the Alternate-Day Diet on basic processes such as systemic inflammation. The premise is, therefore, that the reduction of inflammation reduces disease processes and, as a result, leads to prolonged life.

Prior to the Asthma Study, I had only a hunch, supported by people like Lenny and Marla, that the effects of the diet would be apparent within two to three weeks. The scientific literature provided no indication of how long it took for Calorie Restriction to act on a human disease process such as asthma. My colleagues and I were amazed to see that improvement occurred in the subjects’ symptoms within three or four days.

More recently, the rapid onset of effect of Calorie Restriction on the longevity of fruit flies was demonstrated by Linda Partridge and her colleagues at University College, London. What the researchers found was that when fruit flies were put on a reduced-calorie diet, regardless of their ages, their longevity was increased within 48 hours. If they were then fed normally again, their death rate quickly returned to its original level.

WHAT IT ALL MEANS

The Asthma Study showed that symptoms were alleviated, pulmonary function was improved, and indicators of inflammation and oxidative stress declined as a result of the Alternate-Day Diet in this group of asthma sufferers. These findings, however, are consistent with the results in others who go on the Alternate-Day Diet, most of whom report feeling better within ten to fourteen days, with reduced symptoms of arthritis, allergies, and asthma, and other anecdotally observed improvements, within two weeks.

My colleagues and I believe—based on previous studies, on our own findings, and on personal anecdotal evidence—that the calorie restriction created by Alternate-Day dieting will have similar health benefits, in that it will reduce inflammation and oxidative damage while also helping to control body weight, for the general population. If, as we showed, the diet reduces the inflammation that is responsible for asthma symptoms, it is logical to assume that it will have a similar impact on all kinds of other chronic disorders, including heart disease. In other words, you too can lose weight, become more physically active, elevate your mood, become smarter, and, most important, increase your longevity by following the Alternate-Day Diet.