Friends for Life

by Ellen Sherman

Two men choose to embrace how alike they are instead of focusing on their differences.

The 77-year-old image is faded but familiar: 42 third-graders from Cincinnati’s North Avondale Elementary School. A small child in the third row stands out; John Leahr is the only black boy in the class.

“Almost everything was segregated then,” recalls Herb Heilbrun, an 84-year-old real estate broker, “so we didn’t play together. I wasn’t a racist, but I didn’t have black friends. I just thought that’s the way the world was supposed to be.”

Little did Herb imagine that he and John would be inextricably linked for the next three-quarters of a century—that one of them would be instrumental in saving the other, and that a lesson in friendship would be taught.

More than a decade after the class picture was snapped, World War II broke out. The two men went their separate ways, never really knowing each other. Herb became a bomber pilot assigned to B-17 Flying Fortresses, and John, also wanting to do his part for his country, joined the Tuskegee Experiment.

“I’d always had dreams of flying, but there was no place for black pilots,” John remembers. In response to a lawsuit brought by a student petitioning to fly, a program to train black pilots was started. “The military thought they’d show we couldn’t do it, and close it.” But the Tuskegee Airmen surprised everyone, flying cover for hundreds of missions. Still, it wouldn’t be until 1995, when HBO produced a film about the unit, that the world would hear of the brave exploits of these pilots.

Herb Heilbrun (above right) and John Leahr became friends 69 years after standing close together in their 1928 third-grade class photo.

The thrill of flying outweighed the disappointment John felt over the treatment he and his fellow airmen received. “On our first day of training at Moton Field in Tuskegee,” he remembers, “our officer said, ‘You boys came down here to fly airplanes, not to change social policy. If anybody gives you a hard time off base, you’re on your own. The Army isn’t going to protect you; your life is in your hands.’ ” White men in training to serve their country wouldn’t be greeted so callously, John thought. “It was like he was saying, ‘This is the South, and you’re still black men. Your lives don’t matter to anyone.’ ”

During the war, Herb flew 35 combat missions over Europe. “Once, in December 1944, I was flying over Czechoslovakia,” he recalls. “Eight hundred and fifty flak guns were aimed at us, and I was hit 89 times. But I made it home because I had great cover from our planes.”

Those planes were piloted by black airmen. “Though the bases were segregated, we’d meet in the sky,” John says. In more than 200 escort missions, only about five bombers were lost to enemy fighters.

After the war, Herb returned to Cincinnati, married and started a family. He rarely thought about his time in battle. But one cold day in 1997, he read in the newspaper that his town was honoring the Tuskegee Airmen. “I just wanted to give them a big hug for keeping those German fighter planes away from me,” Herb explains.

He headed over to the reception and began asking the men who’d gathered whether any of them might have flown at the same time he did. They pointed to a distinguished-looking man in the corner. It was John Leahr.

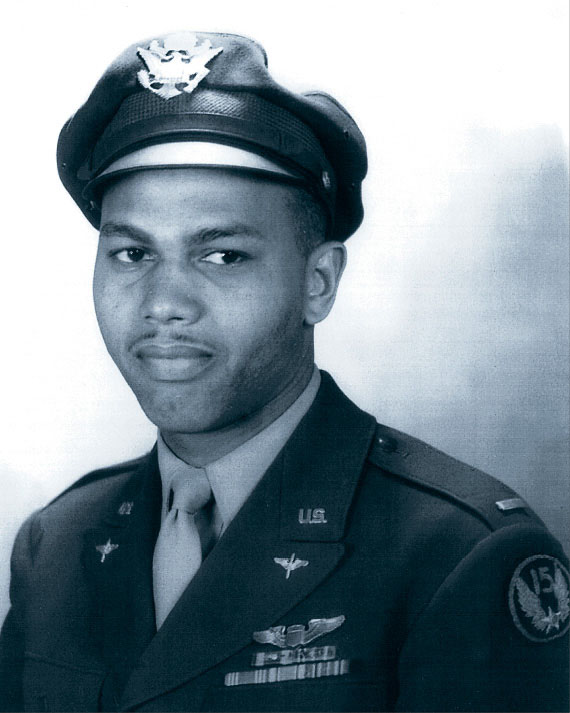

Leahr (in 1945) in his military uniform.

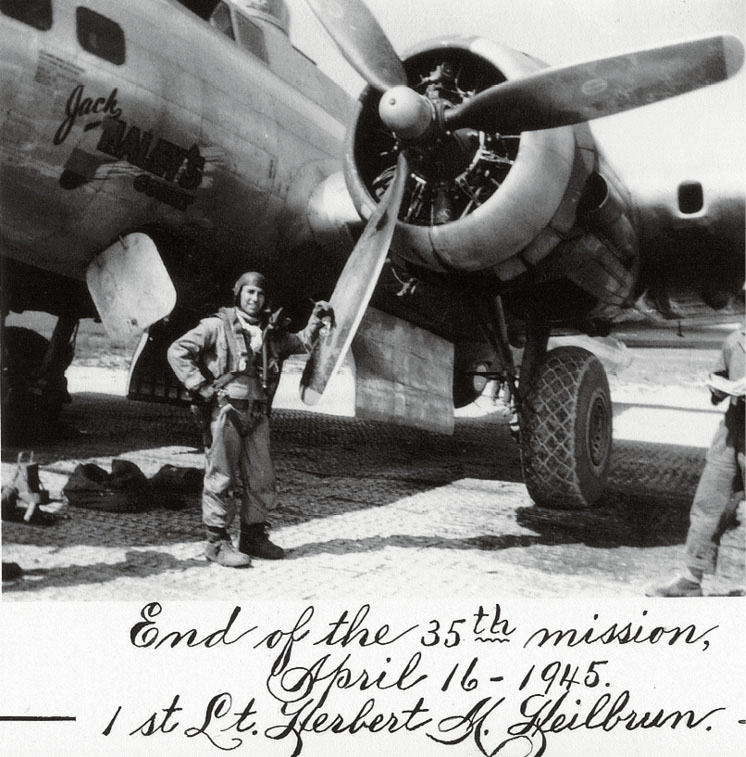

Heilbrun posed next to his WWII B-17 bomber after flying his 35th mission in April 1945.

“This lanky, white fellow comes up and puts his arms around me,” John recalls. “I didn’t know what was going on.” But after comparing mission books, John learned that he had actually flown cover for Herb on two missions in 1944. In fact, John’s plane was among those that helped Herb make it home on that frightening December day.

“These guys were fighters, but they were told not to be aces—just protect the bombers at all costs,” Herb says. “And they did. It was amazing to be able to thank him.”

As John and Herb talked, they realized they’d worked at the same aeronautics plant before the war and at the same Air Force base after. John had gone on to become a stockbroker, but the two men had lived only minutes apart—a few miles from where they attended elementary school.

Herb went home after the reception and began looking for his old class photos. “I got out my third-grade picture, called John up and said, ‘If this little black guy in the third row is you, then this is getting really scary.’ ” Indeed, it was John, standing almost shoulder to shoulder with Herb.

“I couldn’t go through life hating people just because of the color of their skin. I couldn’t not forgive.”

The men began spending time together. Herb learned about John’s homecoming after the war—so different from his own. While parades were given for white servicemen, John and his fellow airmen went uncelebrated. Sometimes they were even targets for scorn. Once, in Memphis with three fellow officers, John suffered a beating. “A guy came along,” John remembers, “and said, ‘I’ve killed niggers before, but I’ve never killed no nigger officers.’ Two white policemen came up and just drove on. Luckily a sailor passed by and stopped the guy. If it wasn’t for him, I’d be dead.”

“If I had gotten killed,” John told Herb, “not a thing would have been said. They would have just sent my body home. It was a terrible thought to have about the country that you’d been willing to die for.”

But to counter any resentment he might feel toward whites after the war, John joined a multiracial church. “I couldn’t go through life hating people just because of the color of their skin,” he says. “I couldn’t not forgive.” And through his wife, a teacher, he began giving talks at schools about his war-time experiences and the importance of overcoming prejudice.

John invited Herb to come to one of his talks. “I knew people faced racism,” Herb admits, “but it never hit home until I heard John speak. And I felt a certain complicity. I hadn’t done anything to make it worse, but I hadn’t done anything to make it better.”

When John asked Herb to join him at the lectern, Herb saw it as a way to make good on a debt he owed to his new friend—and to hundreds like him, who’d been unsung heroes of the war.

“The kids are fascinated hearing John talk,” Herb explains. “Then he introduces me. We give each other a hug. When we show them the picture of our class, they cheer.”

In the fall of 2003, the pair received the Harvard Foundation medal for encouraging racial diversity. “Having Herb tell people how grateful and proud he is of us makes me realize I could have had this relationship for 77 years, not just eight,” says John. “Because of racism, he stayed in his world and I stayed in mine. We don’t want that to happen to two other little boys.”

“Adlai Stevenson once praised Eleanor Roosevelt because she’d rather ‘light a candle than curse the darkness, and her glow has warmed the world,’ ” says Herb. “Johnny and I aren’t about to warm the world, but I think our story has certainly lit a few candles.”

Originally published in the March 2005 issue of Reader’s Digest magazine.

John Leahr died at the age of 94 in March 2015. Herb Heilbrun celebrated his 99th birthday in October 2019 in Cincinnati, where he still lives. In 2017, he marked his 97th birthday by taking a spin in a restored B-17 bomber that took off from Lunken Field at the Cincinnati Municipal Airport.