2.4 Congruence Theory

The notion of congruences was first introduced by Gauss, who gave their definition in his celebrated Disquisitiones Arithmeticae in 1801, though the ancient Greeks and Chinese had the idea first.

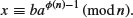

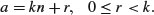

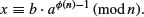

Definition 2.34 Let a be an integer and n a positive integer greater than 1. We define “ ” to be the remainder r when a is divided by n, that is

” to be the remainder r when a is divided by n, that is

(2.89)

We may also say that “r is equal to a reduced modulo n”.

Remark 2.7 It follows from the above definition that  is the integer r such that

is the integer r such that  and

and  , which was known to the ancient Greeks 2000 years ago.

, which was known to the ancient Greeks 2000 years ago.

Example 2.37 The following are some examples of a mod n:

Given the well-defined notion of the remainder of one integer when divided by another, it is convenient to provide a special notion to indicate equality of remainders.

Definition 2.35 Let a and b be integers and n a positive integer. We say that “a is congruent to b modulo n”, denoted by

(2.90)

if n is a divisor of a−b, or equivalently, if  . Similarly, we write

. Similarly, we write

(2.91)

if a is not congruent (or incongruent) to b modulo n, or equivalently, if  . Clearly, for

. Clearly, for  (resp.

(resp.  ), we can write a = kn+b (resp.

), we can write a = kn+b (resp.  ) for some integer K. The integer n is called the modulus.

) for some integer K. The integer n is called the modulus.

Clearly,

and

So, the above definition of congruences, introduced by Gauss in his Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, does not offer any new idea other than the divisibility relation, since “ ” and “

” and “ ” (resp. “

” (resp. “ ” and “

” and “ ”) have the same meaning, although each of them has its own advantages. However, Gauss did present a new way (i.e., congruences) of looking at the old things (i.e., divisibility); this is exactly what we are interested in. It is interesting to note that the ancient Chinese mathematician Ch’in Chiu-Shao (1202–1261) had already noted the idea of congruences in his famous book Mathematical Treatise in Nine Chapters in 1247.

”) have the same meaning, although each of them has its own advantages. However, Gauss did present a new way (i.e., congruences) of looking at the old things (i.e., divisibility); this is exactly what we are interested in. It is interesting to note that the ancient Chinese mathematician Ch’in Chiu-Shao (1202–1261) had already noted the idea of congruences in his famous book Mathematical Treatise in Nine Chapters in 1247.

Definition 2.36 If  , then b is called a residue of a modulo n. If

, then b is called a residue of a modulo n. If  , b is called the least non-negative residue of a modulo n.

, b is called the least non-negative residue of a modulo n.

Remark 2.8 It is common, particularly in computer programs, to denote the least non-negative residue of a modulo n by  . Thus,

. Thus,  if and only if

if and only if  , and, of course,

, and, of course,  if and only if

if and only if  .

.

Example 2.38 The following are some examples of congruences or incongruences.

|

since |

|

|

since |

|

|

since |

|

The congruence relation has many properties in common with the of equality relation. For example, we know from high-school mathematics that equality is

;

; ;

; .

.We shall see that congruence modulo n has the same properties:

Theorem 2.41 Let n be a positive integer. Then the congruence modulo n is

,

,  ;

; , then

, then  ,

,  ;

; and

and  , then

, then  ,

,  .

.Proof:

, hence

, hence  .

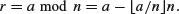

. , then a = kn+b for some integer K. Hence b = a−kn = (−k)n+a, which implies

, then a = kn+b for some integer K. Hence b = a−kn = (−k)n+a, which implies  , since −k is an integer.

, since −k is an integer. and

and  , then a = k1n+b and b = k2n+c. Thus, we can get

, then a = k1n+b and b = k2n+c. Thus, we can get

, since

, since  is an integer.

is an integer.Theorem 2.41 shows that congruence modulo n is an equivalence relation on the set of integers  . But note that the divisibility relation

. But note that the divisibility relation  is reflexive, and transitive but not symmetric; in fact if

is reflexive, and transitive but not symmetric; in fact if  and

and  then a = b, so it is not an equivalence relation. The congruence relation modulo n partitions

then a = b, so it is not an equivalence relation. The congruence relation modulo n partitions  into n equivalence classes. In number theory, we call these classes congruence classes, or residue classes.

into n equivalence classes. In number theory, we call these classes congruence classes, or residue classes.

Definition 2.37 If  , then a is called a residue of x modulo n. The residue class of a modulo n, denoted by [a]n (or just [a] if no confusion will be caused), is the set of all those integers that are congruent to a modulo n. That is,

, then a is called a residue of x modulo n. The residue class of a modulo n, denoted by [a]n (or just [a] if no confusion will be caused), is the set of all those integers that are congruent to a modulo n. That is,

(2.92)

Note that writing  is the same as writing

is the same as writing  .

.

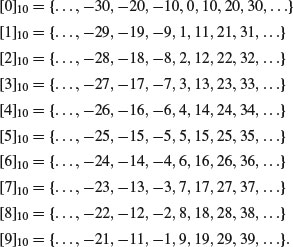

Example 2.39 Let n = 5. Then there are five residue classes, modulo 5, namely the sets:

, , |

, , |

, , |

, , |

. . |

The first set contains all those integers congruent to 0 modulo 5, the second set contains all those congruent to 1 modulo 5, ..., and the fifth (i.e., the last) set contains all those congruent to 4 modulo 5. So, for example, the residue class [2]5 can be represented by any one of the elements in the set

Clearly, there are infinitely many elements in the set [2]5.

Example 2.40 In residue classes modulo 2, [0]2 is the set of all even integers, and [1]2 is the set of all odd integers:

Example 2.41 In congruence modulo 5, we have

We also have

So, clearly, [4]5 = [9]5.

Example 2.42 Let n = 7. There are seven residue classes, modulo 7. In each of these seven residue classes, there is exactly one least residue of x modulo 7. So the complete set of all least residues x modulo 7 is  .

.

Definition 2.38 The set of all residue classes modulo n, often denoted by  or

or  , is

, is

Remark 2.9 One often sees the definition

(2.94)

which should be read as equivalent to (2.93) with the understanding that 0 represents [0]n, 1 represents [1]n, 2 represents [2]n, and so on; each class is represented by its least non-negative residue, but the underlying residue classes must be kept in mind. For example, a reference to −a as a member of  is a reference to [n−a]n, provided

is a reference to [n−a]n, provided  , since

, since  .

.

The following theorem gives some elementary properties of residue classes:

Theorem 2.42 Let n be a positive integer. Then we have

;

; , and they contain all of the integers.

, and they contain all of the integers.Proof:

, it follows from the transitive property of congruence that an integer is congruent to a modulo n if and only if it is congruent to b modulo n. Thus, [a]n = [b]n. To prove the converse, suppose [a]n = [b]n. Because

, it follows from the transitive property of congruence that an integer is congruent to a modulo n if and only if it is congruent to b modulo n. Thus, [a]n = [b]n. To prove the converse, suppose [a]n = [b]n. Because  and

and  , Thus,

, Thus,  .

. and

and  . From the symmetric and transitive properties of congruence, it follows that

. From the symmetric and transitive properties of congruence, it follows that  . From part (1) of this theorem, it follows that [a]n = [b]n. Thus, either [a]n and [b]n are disjoint or identical.

. From part (1) of this theorem, it follows that [a]n = [b]n. Thus, either [a]n and [b]n are disjoint or identical.

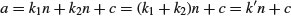

and so [a]n = [r]n. This implies that a is in one of the residue classes

and so [a]n = [r]n. This implies that a is in one of the residue classes  Because the integers

Because the integers  are incongruent modulo n, it follows that there are exactly n residue classes modulo n.

are incongruent modulo n, it follows that there are exactly n residue classes modulo n.

Definition 2.39 Let n be a positive integer. A set of integers  is called a complete system of residues modulo n, if the set contains exactly one element from each residue class modulo n.

is called a complete system of residues modulo n, if the set contains exactly one element from each residue class modulo n.

Example 2.43 Let n = 4. Then  is a complete system of residues modulo 4, since

is a complete system of residues modulo 4, since  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . Of course, it can be easily verified that

. Of course, it can be easily verified that  is another complete system of residues modulo 4. It is clear that the simplest complete system of residues modulo 4 is

is another complete system of residues modulo 4. It is clear that the simplest complete system of residues modulo 4 is  , the set of all non-negative least residues modulo 4.

, the set of all non-negative least residues modulo 4.

Example 2.44 Let n = 7. Then

is a complete system of residues modulo 7, for any  . To see this let us first evaluate the powers of 3 modulo 7:

. To see this let us first evaluate the powers of 3 modulo 7:

| 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

hence, the result follows from x = 0. Now the general result follows immediately, since (x+3i)−(x+3j) = 3i−3j.

Theorem 2.43 Let n be a positive integer and s a set of integers. s is a complete system of residues modulo n if and only if s contains n elements and no two elements of s are congruent, modulo n.

Proof: If s is a complete system of residues, then the two conditions are satisfied. To prove the converse, we note that if no two elements of s are congruent, the elements of s are in different residue classes modulo n. Since s has n elements, all the residue classes must be represented among the elements of s. Thus, s is a complete system of residues modulo n.

We now introduce one more type of system of residues, the reduced system of residues modulo n.

Definition 2.40 Let [a]n be a residue class modulo n. We say that [a]n is relatively prime to n if each element in [a]n is relatively prime to n.

Example 2.45 Let n = 10. Then the ten residue classes, modulo 10, are as follows:

Clearly, [1]10, [3]10, [7]10, and [9]10 are residue classes that are relatively prime to 10.

Proposition 2.1 If a residue class modulo n has one element which is relatively prime to n, then every element in that residue class is relatively prime to n.

Proposition 2.2 If n is prime, then every residue class modulo n (except [0]n) is relatively prime to n.

Definition 2.41 Let n be a positive integer, then  is the number of residue classes modulo n, which is relatively prime to n. A set of integers

is the number of residue classes modulo n, which is relatively prime to n. A set of integers  is called a reduced system of residues, if the set contains exactly one element from each residue class modulo n which is relatively prime to n.

is called a reduced system of residues, if the set contains exactly one element from each residue class modulo n which is relatively prime to n.

Example 2.46 In Example 2.45, we know that [1]10, [3]10, [7]10, and [9]10 are residue classes that are relatively prime to 10, so by choosing −29 from [1]10, −17 from [3]10, 17 from [7]10 and 39 from [9]10, we get a reduced system of residues modulo 10:  . Similarly,

. Similarly,  is another reduced system of residues modulo 10.

is another reduced system of residues modulo 10.

One method of obtaining a reduced system of residues is to start with a complete system of residues and delete those elements that are not relatively prime to the modulus n. Thus, the simplest reduced system of residues  is just the collections of all integers in the set

is just the collections of all integers in the set  that are relatively prime to n.

that are relatively prime to n.

Theorem 2.44 Let n be a positive integer, and s a set of integers. Then s is a reduced system of residues  if and only if

if and only if

elements;

elements; ;

;Proof: It is obvious that a reduced system of residues satisfies the three conditions. To prove the converse, we suppose that s is a set of integers having the three properties. Because no two elements of s are congruent, the elements are in different residues modulo n. Since the elements of s are relatively prime n, there are in residue classes that are relatively prime n. Thus, the  elements of s are distributed among the

elements of s are distributed among the  residue classes that are relatively prime n, one in each residue class. Therefore, s is a reduced system of residues modulo n.

residue classes that are relatively prime n, one in each residue class. Therefore, s is a reduced system of residues modulo n.

Corollary 2.3 Let  be a reduced system of residues modulo m, and suppose that

be a reduced system of residues modulo m, and suppose that  . Then

. Then  is also a reduced system of residues modulo n.

is also a reduced system of residues modulo n.

Proof: Left as an exercise.

The finite set  is closely related to the infinite set

is closely related to the infinite set  . So it is natural to ask if it is possible to define addition and multiplication in

. So it is natural to ask if it is possible to define addition and multiplication in  and do some reasonable kind of arithmetic there. Surprisingly, the addition, subtraction, and multiplication in

and do some reasonable kind of arithmetic there. Surprisingly, the addition, subtraction, and multiplication in  will be much the same as that in

will be much the same as that in  .

.

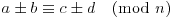

Theorem 2.45 For all  and

and  , if

, if  and

and  . then

. then

;

; ;

; ,

,  .

.Proof:

. Then a+c = (k+l)n+b+d. Therefore, a+c = b+d+tn,

. Then a+c = (k+l)n+b+d. Therefore, a+c = b+d+tn,  . Consequently,

. Consequently,  , which is what we wished to show. The case for subtraction is left as an exercise.

, which is what we wished to show. The case for subtraction is left as an exercise.

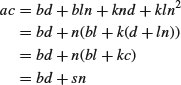

. Thus,

. Thus,  .

. (base step) and

(base step) and  (inductive hypothesis). Then by Part (2) we have

(inductive hypothesis). Then by Part (2) we have

Theorem 2.45 is equivalent to the following theorem, since

Theorem 2.46 For all  , if [a]n = [b]n, [c]n = [d]n, then

, if [a]n = [b]n, [c]n = [d]n, then

,

, ,

, .

.The fact that the congruence relation modulo n is stable for addition (subtraction) and multiplication means that we can define binary operations, again called addition (subtraction) and multiplication on the set of  of equivalence classes modulo n as follows (in case only one n is being discussed, we can simply write [x] for the class [x]n):

of equivalence classes modulo n as follows (in case only one n is being discussed, we can simply write [x] for the class [x]n):

(2.95)

(2.96)

(2.97)

Example 2.47 Let n = 12, then

In many cases, we may still prefer to write the above operations as follows:

We summarize the properties of addition and multiplication modulo n in the following two theorems.

Theorem 2.47 The set  of integers modulo n has the following properties with respect to addition:

of integers modulo n has the following properties with respect to addition:

, for all

, for all  ;

; ;

; ;

; .

.Proof: These properties follow directly from the stability and the definition of the operation in  .

.

Theorem 2.48 The set  of integers modulo n has the following properties with respect to multiplication:

of integers modulo n has the following properties with respect to multiplication:

, for all

, for all  ;

; , for all

, for all  ;

; , for all

, for all  ;

; , for all

, for all  .

.Proof: These properties follow directly from the stability of the operation in  and the corresponding properties of

and the corresponding properties of  .

.

The division a/b (we assume a/b is in lowest terms and  ) in

) in  , however, will be more of a problem; sometimes you can divide, sometimes you cannot. For example, let n = 12 again, then

, however, will be more of a problem; sometimes you can divide, sometimes you cannot. For example, let n = 12 again, then

|

(no problem), |

|

(impossible). |

Why is division sometimes possible (e.g.,  ) and sometimes impossible (e.g.,

) and sometimes impossible (e.g.,  )? The problem is with the modulus n; if n is a prime number, then the division

)? The problem is with the modulus n; if n is a prime number, then the division  is always possible and unique, whilst if n is a composite then the division

is always possible and unique, whilst if n is a composite then the division  may be not possible or the result may be not unique. Let us observe two more examples, one with n = 13 and the other with n = 14. First note that

may be not possible or the result may be not unique. Let us observe two more examples, one with n = 13 and the other with n = 14. First note that  if and only if

if and only if  is possible, since multiplication modulo n is always possible. We call

is possible, since multiplication modulo n is always possible. We call  the multiplicative inverse (or the modular inverse) of b modulo n. Now let n = 13 be a prime, then the following table gives all the values of the multiplicative inverses

the multiplicative inverse (or the modular inverse) of b modulo n. Now let n = 13 be a prime, then the following table gives all the values of the multiplicative inverses  for

for  :

:

This means that division in  is always possible and unique. On the other hand, if n = 14 (the n now is a composite), then

is always possible and unique. On the other hand, if n = 14 (the n now is a composite), then

This means that only the numbers 1, 3, 5, 9, 11 and 13 have multiplicative inverses modulo 14, or equivalently only those divisions by 1, 3, 5, 9, 11 and 13 modulo 14 are possible. This observation leads to the following important results:

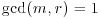

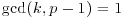

Theorem 2.49 The multiplicative inverse 1/b modulo n exists if and only if  .

.

But how many b’s satisfy  ? The following result answers this question.

? The following result answers this question.

Corollary 2.4 There are  numbers b for which

numbers b for which  exists.

exists.

Example 2.48 Let n = 21. Since  , there are twelve values of b for which

, there are twelve values of b for which  exists. In fact, the multiplicative inverse modulo 21 only exists for each of the following b:

exists. In fact, the multiplicative inverse modulo 21 only exists for each of the following b:

Corollary 2.5 The division a/b modulo n (assume that a/b is in lowest terms) is possible if and only if  exists, that is, if and only if

exists, that is, if and only if  .

.

Example 2.49 Compute  whenever it is possible. By the multiplicative inverses of

whenever it is possible. By the multiplicative inverses of  in the previous table, we just need to calculate

in the previous table, we just need to calculate  :

:

As can be seen, addition (subtraction) and multiplication are always possible in  , with n>1, since

, with n>1, since  is a ring. Note also that

is a ring. Note also that  with n prime is an Abelian group with respect to addition, and all the nonzero elements in

with n prime is an Abelian group with respect to addition, and all the nonzero elements in  form an Abelian group with respect to multiplication (i.e., a division is always possible for any two nonzero elements in

form an Abelian group with respect to multiplication (i.e., a division is always possible for any two nonzero elements in  if n is prime); hence

if n is prime); hence  with n prime is a field. That is:

with n prime is a field. That is:

Theorem 2.50  is a field if and only if n is prime.

is a field if and only if n is prime.

The above results only tell us when the multiplicative inverse 1/a modulo n is possible, without mentioning how to find the inverse. To actually find the multiplicative inverse, we let

(2.98)

which is equivalent to

(2.99)

Since

(2.100)

Thus, finding the multiplicative inverse  is the same as finding the solution of the linear Diophantine equation ax−ny = 1, which, as we know, can be solved by using the continued fraction expansion of a/n or by using Euclid’s algorithm.

is the same as finding the solution of the linear Diophantine equation ax−ny = 1, which, as we know, can be solved by using the continued fraction expansion of a/n or by using Euclid’s algorithm.

Example 2.50 Find

,

, .

.Solution

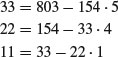

as follows:

as follows:

, by Theorem 2.49, the equation 154x−801y = 1 is soluble. We now rewrite the above resulting equations

, by Theorem 2.49, the equation 154x−801y = 1 is soluble. We now rewrite the above resulting equations

So,  . That is,

. That is,

The above procedure used to find the x and y in ax+by = 1 can be generalized to find the x and y in ax+by = c; this procedure is usually called the extended Euclid’s algorithm.

Congruences have much in common with equations. In fact, the linear congruence  is equivalent to the linear Diophantine equation ax−ny = b. That is,

is equivalent to the linear Diophantine equation ax−ny = b. That is,

(2.101)

Thus, linear congruences can be solved by using the continued fraction method just as for linear Diophantine equations.

Theorem 2.51 Let  . If

. If  , then the linear congruence

, then the linear congruence

(2.102)

has no solution.

Proof: We will prove the contrapositive of the assertion: If  has a solution, then

has a solution, then  . Suppose that s is a solution. Then

. Suppose that s is a solution. Then  , and from the definition of the congruence,

, and from the definition of the congruence,  , or from the definition of divisibility, as−b = kn for some integer K. Since

, or from the definition of divisibility, as−b = kn for some integer K. Since  and

and  , it follows that

, it follows that  .

.

Theorem 2.52 Let  . Then the linear congruence

. Then the linear congruence  has solutions if and only if

has solutions if and only if  .

.

Proof: Follows from Theorem 2.51.

Theorem 2.53 Let  . Then the linear congruence

. Then the linear congruence  has exactly one solution.

has exactly one solution.

Proof: If  , then there exist x and y such that ax+ny = 1. Multiplying by b gives

, then there exist x and y such that ax+ny = 1. Multiplying by b gives

As a(xb)−b is a multiple of n, or  , the least residue of xb modulo n is then a solution of the linear congruence. The uniqueness of the solution is left as an exercise.

, the least residue of xb modulo n is then a solution of the linear congruence. The uniqueness of the solution is left as an exercise.

Theorem 2.54 Let  and suppose that

and suppose that  . Then the linear congruence

. Then the linear congruence

(2.103)

has exactly d solutions modulo n. These are given by

(2.104)

where t is the solution, unique modulo n/d, of the linear congruence

(2.105)

Proof: By Theorem 2.52, the linear congruence has solutions since  . Now let t be be such a solution, then t+k(n/d) for

. Now let t be be such a solution, then t+k(n/d) for  are also solutions, since

are also solutions, since

Example 2.51 Solve the linear congruence  . Notice first that

. Notice first that

Now we use the Euclid’s algorithm to find  as follows:

as follows:

Since  and

and  , by Theorem 2.31, the equation 154x−801y = 22 is soluble. Now we rewrite the above resulting equations

, by Theorem 2.31, the equation 154x−801y = 22 is soluble. Now we rewrite the above resulting equations

and work backwards on the above new equations

So,  . By Theorems 2.53 and 2.54,

. By Theorems 2.53 and 2.54,  is the only solution to the simplified congruence:

is the only solution to the simplified congruence:

since  . By Theorem 2.54, there are, in total, eleven solutions to the congruence

. By Theorem 2.54, there are, in total, eleven solutions to the congruence  , as follows:

, as follows:

Thus,

are the eleven solutions to the original congruence  .

.

Remark 2.10 To find the solution for the linear Diophantine equation

(2.106)

is equivalent to finding the quotient of the modular division

(2.107)

which is, again, equivalent to finding the multiplicative inverse

(2.108)

because if  modulo n exists, the multiplication

modulo n exists, the multiplication  is always possible.

is always possible.

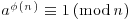

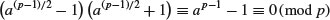

Theorem 2.55 (Fermat’s little theorem) Let a be a positive integer and  . If p is prime, then

. If p is prime, then

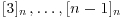

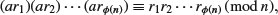

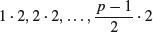

Proof: First notice that the residues modulo p of  are

are  in some order, because no two of them can be equal. So, if we multiply them together, we get

in some order, because no two of them can be equal. So, if we multiply them together, we get

This means that

Now we can cancel the (p−1)! since  , and the result thus follows.

, and the result thus follows.

There is a more convenient and more general form of Fermat’s little theorem:

(2.110)

for  . The proof is easy: If

. The proof is easy: If  , we simply multiply (2.109) by a. If not, then

, we simply multiply (2.109) by a. If not, then  . So

. So  .

.

Fermat’s theorem has several important consequences which are very useful in compositeness; one of the these consequences is as follows:

Corollary 2.6 (Converse of the Fermat little theorem, 1640) Let n be an odd positive integer. If  and

and

(2.111)

then n is composite.

Remark 2.11 In 1640, Fermat made a false conjecture that all the numbers of the form  were prime. Fermat really should not have made such a “stupid” conjecture, since F5 can be relatively easily verified to be composite, just by using his own recently discovered theorem – Fermat’s little theorem:

were prime. Fermat really should not have made such a “stupid” conjecture, since F5 can be relatively easily verified to be composite, just by using his own recently discovered theorem – Fermat’s little theorem:

Thus, by Fermat’s little theorem, 232+1 is not prime!

Based on Fermat’s little theorem, Euler established a more general result in 1760:

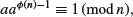

Theorem 2.56 (Euler’s theorem) Let a and n be positive integers with  . Then

. Then

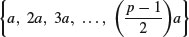

Proof: Let  be a reduced residue system modulo n. Then

be a reduced residue system modulo n. Then  is also a residue system modulo n. Thus we have

is also a residue system modulo n. Thus we have

since  , being a reduced residue system, must be congruent in some order to

, being a reduced residue system, must be congruent in some order to  . Hence,

. Hence,

which implies that

It can be difficult to find the order1 of an element a modulo n but sometimes it is possible to improve (2.112) by proving that every integer a modulo n must have an order smaller than the number  – this order is actually a number that is a factor of

– this order is actually a number that is a factor of  .

.

Theorem 2.57 (Carmichael’s theorem) Let a and n be positive integers with  . Then

. Then

(2.113)

where  is Carmichael’s function, given in Definition 2.32.

is Carmichael’s function, given in Definition 2.32.

Proof: Let  . We shall show that

. We shall show that

for  , since this implies that

, since this implies that  . If

. If  or a power of an odd prime, then by Definition 2.32,

or a power of an odd prime, then by Definition 2.32,  , so

, so  . Since

. Since  ,

,  . The case that

. The case that  is a power of 2 greater than 4 is left as an exercise.

is a power of 2 greater than 4 is left as an exercise.

Note that  will never exceed

will never exceed  and is often much smaller than

and is often much smaller than  ; it is the value of the largest order it is possible to have.

; it is the value of the largest order it is possible to have.

Example 2.52 Let a = 11 and n = 24. Then  ,

,  . So,

. So,

That is, ord24(11) = 2.

In 1770 Edward Waring (1734–1793) published the following result, which is attributed to John Wilson (1741–1793).

Theorem 2.58 (Wilson’s theorem) If p is a prime, then

(2.114)

Proof: It suffices to assume that p is odd. Now to every integer a with 0<a<p there is a unique integer  with

with  such that

such that  . Further if

. Further if  then

then  whence a = 1 or a = p−1. Thus the set

whence a = 1 or a = p−1. Thus the set  can be divided into (p−3)/2 pairs

can be divided into (p−3)/2 pairs  with

with  . Hence we have

. Hence we have  , and so

, and so  , as required.

, as required.

Theorem 2.59 (Converse of Wilson’s theorem) If n is an odd positive integer greater than 1 and

(2.115)

then n is a prime.

Remark 2.12 Prime p is called a Wilson prime if

(2.116)

where

is an integer, or equivalently if

(2.117)

For example, p = 5, 13, 563 are Wilson primes, but 599 is not since

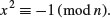

It is not known whether there are infinitely many Wilson primes; to date, the only known Wilson primes for  are p = 5, 13, 563. A prime p is called a Wieferich prime, named after A. Wieferich, if

are p = 5, 13, 563. A prime p is called a Wieferich prime, named after A. Wieferich, if

(2.118)

To date, the only known Wieferich primes for  are p = 1093 and 3511.

are p = 1093 and 3511.

In what follows, we shall show how to use Euler’s theorem to calculate the multiplicative inverse modulo n, and hence the solutions of a linear congruence.

Theorem 2.60 Let x be the multiplicative inverse 1/a modulo n. If  , then

, then

(2.119)

is given by

(2.120)

Proof: By Euler’s theorem, we have  . Hence

. Hence

and  is the multiplicative inverse of a modulo n, as desired.

is the multiplicative inverse of a modulo n, as desired.

Corollary 2.7 Let x be the division b/a modulo n (b/a is assumed to be in lowest terms). If  , then

, then

(2.121)

is given by

(2.122)

Corollary 2.8 If  , then the solution of the linear congruence

, then the solution of the linear congruence

(2.123)

is given by

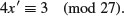

Example 2.53 Solve the congruence  . First note that because

. First note that because  , the congruence has exactly one solution. Using (2.124) we get

, the congruence has exactly one solution. Using (2.124) we get

Example 2.54 Solve the congruence  . First note that as

. First note that as  and

and  , the congruence has exactly five solutions modulo 135. To find these five solutions, we divide by 5 and get a new congruence

, the congruence has exactly five solutions modulo 135. To find these five solutions, we divide by 5 and get a new congruence

To solve this new congruence, we get

Therefore, the five solutions are as follows:

Next we shall introduce a method for solving systems of linear congruences. The method, widely known as the Chinese Remainder theorem (or just CRT, for short), was discovered by the ancient Chinese mathematician Sun Tsu (who lived sometime between 200 B.C. and 200 A.D.).

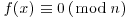

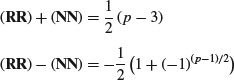

Theorem 2.61 (The Chinese Remainder theorem CRT) If m1, m2, ..., mn are pairwise relatively prime and greater than 1, and a1, a2, ..., an are any integers, then there is a solution x to the following simultaneous congruences:

If x and  are two solutions, then

are two solutions, then  , where M = m1m2...mn.

, where M = m1m2...mn.

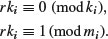

Proof: Existence: Let us first solve a special case of the simultaneous congruences (2.125), where i is some fixed subscript,

Let ki = m1m2...mi−1mi+1...mn. Then ki and mi are relatively prime, so we can find integers r and s such that rki+smi = 1. This gives the congruences:

Since  all divide ki, it follows that xi = rki satisfies the simultaneous congruences:

all divide ki, it follows that xi = rki satisfies the simultaneous congruences:

For each subscript i,  , we find such an xi. Now to solve the system of the simultaneous congruences (2.125), set x = a1x1+a2x2+...+anxn. Then

, we find such an xi. Now to solve the system of the simultaneous congruences (2.125), set x = a1x1+a2x2+...+anxn. Then  for each i,

for each i,  , such that x is a solution of the simultaneous congruences.

, such that x is a solution of the simultaneous congruences.

Uniqueness: Let  be another solution to the simultaneous congruences (2.125), but different from the solution x, so that

be another solution to the simultaneous congruences (2.125), but different from the solution x, so that  for each xi. Then

for each xi. Then  for each i. So mi divides

for each i. So mi divides  for each i; hence the least common multiple of all the mj’s divides

for each i; hence the least common multiple of all the mj’s divides  . But since the mi are pairwise relatively prime, this least common multiple is the product m. So

. But since the mi are pairwise relatively prime, this least common multiple is the product m. So  .

.

Remark 2.13 If the system of the linear congruences (2.125) is soluble, then its solution can be conveniently described as follows:

where

for  .

.

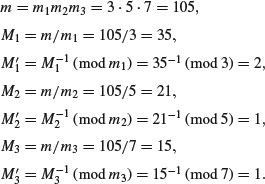

Example 2.55 Consider the Sun Zi problem:

By (2.126), we have

Hence,

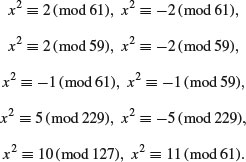

The congruences  we have studied so far are a special type of congruence; they are all linear congruences. In this section, we shall study the higher degree congruences, particularly the quadratic congruences.

we have studied so far are a special type of congruence; they are all linear congruences. In this section, we shall study the higher degree congruences, particularly the quadratic congruences.

Definition 2.42 Let m be a positive integer, and let

be any polynomial with integer coefficients. Then a high-order congruence or a polynomial congruence is a congruence of the form

(2.127)

A polynomial congruence is also called a polynomial congruential equation.

Let us consider the polynomial congruence

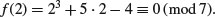

This congruence holds when x = 2, since

Just as for algebraic equations, we say that x = 2 is a root or a solution of the congruence. In fact, any value of x which satisfies the following condition

is also a solution of the congruence. In general, as in linear congruence, when a solution x0 has been found, all values x for which

are also solutions. But by convention, we still consider them as a single solution. Thus, our problem is to find all incongruent (different) solutions of  . In general, this problem is very difficult, and many techniques of solution depend partially on trial-and-error methods. For example, to find all solutions of the congruence

. In general, this problem is very difficult, and many techniques of solution depend partially on trial-and-error methods. For example, to find all solutions of the congruence  , we could certainly try all values

, we could certainly try all values  (or the numbers in the complete residue system modulo n), and determine which of them satisfy the congruence; this would give us the total number of incongruent solutions modulo n.

(or the numbers in the complete residue system modulo n), and determine which of them satisfy the congruence; this would give us the total number of incongruent solutions modulo n.

Theorem 2.62 Let M = m1m2...mn, where  are pairwise relatively prime. Then the integer x0 is a solution of

are pairwise relatively prime. Then the integer x0 is a solution of

(2.128)

if and only if x0 is a solution of the system of polynomial congruences:

(2.129)

If x and  are two solutions, then

are two solutions, then  , where M = m1m2...mn.

, where M = m1m2...mn.

Proof: If  , then obviously

, then obviously  , for

, for  . Conversely, suppose a is a solution of the system

. Conversely, suppose a is a solution of the system

Then f(a) is a solution of the system

and it follows from the Chinese Remainder theorem that  . Thus, a is a solution of

. Thus, a is a solution of  .

.

We now restrict ourselves to quadratic congruences, the simplest possible nonlinear polynomial congruences.

Definition 2.43 A quadratic congruence is a congruence of the form:

where  . To solve the congruence is to find an integral solution for x which satisfies the congruence.

. To solve the congruence is to find an integral solution for x which satisfies the congruence.

In most cases, it is sufficient to study the above congruence rather than the following more general quadratic congruence

since if  and b is even or n is odd, then the congruence 2.31 can be reduced to a congruence of type (2.130). The problem can even be further reduced to solving a congruence of the type (if

and b is even or n is odd, then the congruence 2.31 can be reduced to a congruence of type (2.130). The problem can even be further reduced to solving a congruence of the type (if  , where

, where  are distinct primes, and

are distinct primes, and  are positive integers):

are positive integers):

(2.132)

because solving the congruence(2.132) is equivalent to solving the following system of congruences:

(2.133)

In what follows, we shall be only interested in quadratic congruences of the form

(2.134)

where p is an odd prime and  .

.

Definition 2.44 Let a be any integer and n a natural number, and suppose that  . Then a is called a quadratic residue modulo n if the congruence

. Then a is called a quadratic residue modulo n if the congruence

is soluble. Otherwise, it is called a quadratic non-residue modulo n.

Remark 2.14 Similarly, we can define the cubic residues, and fourth-power residues, etc. For example, a is a Kth power residue modulo n if the congruence

(2.135)

is soluble. Otherwise, it is a Kth power non-residue modulo n.

Theorem 2.63 Let p be an odd prime and a an integer not divisible by p. Then the congruence

(2.136)

has either no solution or exactly two congruence solutions modulo p.

Proof: If x and y are solutions to  , then

, then  , that is,

, that is,  . Since x2−y2 = (x+y)(x−y), we must have

. Since x2−y2 = (x+y)(x−y), we must have  or

or  , that is,

, that is,  . Hence, any two distinct solutions modulo p differ only by a factor of −1.

. Hence, any two distinct solutions modulo p differ only by a factor of −1.

Example 2.56 Find the quadratic residues and quadratic nonresidues for moduli 5, 7, 11, 15, 23, respectively.

The above example illustrates the following two theorems:

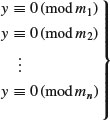

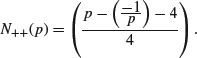

Theorem 2.64 Let p be an odd prime and N(p) the number of consecutive pairs of quadratic residues modulo p in the interval [1, p−1]. Then

(2.137)

Proof: (Sketch) The complete proof of this theorem can be found in [1] and [2]; here we only give a sketch of the proof. Let (RR), (RN), (NR) and (NN) denote the number of pairs of two quadratic residues, of a quadratic residue followed by a quadratic non-residue, of a quadratic non-residue followed by a quadratic residue, of two quadratic non-residues, among pairs of consecutive positive integers less than p, respectively. Then

Hence

Remark 2.15 Similarly, let  denote the number of consecutive triples of quadratic residues in the interval [1, p−1], where p is odd prime. Then

denote the number of consecutive triples of quadratic residues in the interval [1, p−1], where p is odd prime. Then

(2.138)

where  .

.

Example 2.57 For p = 23, there are five consecutive pairs of quadratic residues, namely, (1, 2), (2, 3), (3, 4), (8, 9), and (12, 13), modulo 23; there is also one consecutive triple of quadratic residues, namely, (1, 2, 3), modulo 23.

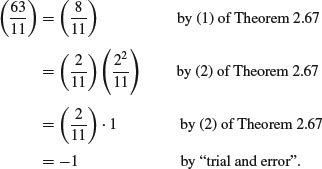

Theorem 2.65 Let p be an odd prime. Then there are exactly (p−1)/2 quadratic residues and exactly (p−1)/2 quadratic nonresidues modulo p.

Proof: Consider the p−1 congruences:

Since each of the above congruences has either no solution or exactly two congruence solutions modulo p, there must be exactly (p−1)/2 quadratic residues modulo p among the integers  . The remaining

. The remaining

positive integers less than p−1 are quadratic nonresidues modulo p.

Example 2.58 Again for p = 23, there are eleven quadratic residues, and eleven quadratic nonresidues modulo 23.

Euler devised a simple criterion for deciding whether an integer a is a quadratic residue modulo a prime number p.

Theorem 2.66 (Euler’s criterion) Let p be an odd prime and  . Then a is a quadratic residue modulo p if and only if

. Then a is a quadratic residue modulo p if and only if

Proof: Using Fermat’s little theorem, we find that

and thus  . If a is a quadratic residue modulo p, then there exists an integer x0 such that

. If a is a quadratic residue modulo p, then there exists an integer x0 such that  . By Fermat’s little theorem, we have

. By Fermat’s little theorem, we have

To prove the converse, we assume that  . If G is a primitive root modulo p (G is a primitive root modulo p if

. If G is a primitive root modulo p (G is a primitive root modulo p if  ; we shall formally define primitive roots in Section 2.5), then there exists a positive integer t such that

; we shall formally define primitive roots in Section 2.5), then there exists a positive integer t such that  . Then

. Then

which implies that

Thus, t is even, and so

which implies that a is a quadratic residue modulo p.

Euler’s criterion is not very useful as a practical test for deciding whether or not an integer is a quadratic residue, unless the modulus is small. Euler’s studies on quadratic residues were further developed by Legendre, who introduced the Legendre symbol.

Definition 2.45 Let p be an odd prime and a an integer. Suppose that  . Then the Legendre symbol,

. Then the Legendre symbol,  , is defined by

, is defined by

(2.139)

We shall use the notation  to denote that a is a quadratic residue modulo p; similarly,

to denote that a is a quadratic residue modulo p; similarly,  will be used to denote that a is a quadratic nonresidue modulo p.

will be used to denote that a is a quadratic nonresidue modulo p.

Example 2.59 Let p = 7 and

Then

Some elementary properties of the Legendre symbol, which can be used to evaluate it, are given in the following theorem.

Theorem 2.67 Let p be an odd prime, and a and b integers that are relatively prime to p. Then

, then

, then  ;

; , and so

, and so  ;

; ;

; ;

; .

.Proof: Assume p is an odd prime and  .

.

, then

, then  has a solution if and only if

has a solution if and only if  has a solution. Hence

has a solution. Hence  .

. clearly has a solution, namely a, so

clearly has a solution, namely a, so  .

.(2.140)

(2.141)

(2.142)

This completes the proof.

Corollary 2.9 Let p be an odd prime. Then

(2.143)

Proof: If  , then p = 4k+1 for some integer K. Thus,

, then p = 4k+1 for some integer K. Thus,

so that  . The proof for

. The proof for  is similar.

is similar.

Example 2.60 Does  have a solution? We first evaluate the Legendre symbol

have a solution? We first evaluate the Legendre symbol  corresponding to the quadratic congruence as follows:

corresponding to the quadratic congruence as follows:

Therefore, the quadratic congruence  has no solution.

has no solution.

To avoid the “trial-and-error” in the above and similar examples, we introduce in the following the so-called Gauss’s lemma for evaluating the Legendre symbol.

Definition 2.46 Let  and

and  . Then the least residue of a modulo n is the integer

. Then the least residue of a modulo n is the integer  in the interval (−n/2, n/2] such that

in the interval (−n/2, n/2] such that  . We denote the least residue of a modulo n by LRn(a).

. We denote the least residue of a modulo n by LRn(a).

Example 2.61 The set  is a complete set of of the least residues modulo 11. Thus, LR11(21) = −1 since

is a complete set of of the least residues modulo 11. Thus, LR11(21) = −1 since  ; similarly, LR11(99) = 0 and LR11(70) = 4.

; similarly, LR11(99) = 0 and LR11(70) = 4.

Lemma 2.3 (Gauss’s lemma) Let p be an odd prime number and suppose that  . Further let

. Further let  be the number of integers in the set

be the number of integers in the set

whose least residues modulo p are negative, then

(2.144)

Proof: When we reduce the following numbers (modulo p)

to lie in set

then no two different numbers ma and na can go to the same numbers. Further, it cannot happen that ma goes to K and na goes to −k, because then  , and hence (multiplying by the inverse of a),

, and hence (multiplying by the inverse of a),  , which is impossible. Hence, when reducing the numbers

, which is impossible. Hence, when reducing the numbers

we get exactly one of −1 and 1, exactly one of −2 and 2, ..., exactly one of −(p−1)/2 and (p−1)/2. Hence, modulo p, we get

Cancelling the numbers  , we have

, we have

By Euler’s criterion, we have  Since

Since  , we must have

, we must have  .

.

Example 2.62 Use Gauss’s lemma to evaluate the Legendre symbol  . By Gauss’s lemma,

. By Gauss’s lemma,  , where

, where  is the number of integers in the set

is the number of integers in the set

whose least residues modulo 11 are negative. Clearly,

So there are 3 least residues that are negative. Thus,  . Therefore,

. Therefore,  . Consequently, the quadratic congruence

. Consequently, the quadratic congruence  is not solvable.

is not solvable.

Remark 2.16 Gauss’s lemma is similar to Euler’s criterion in the following ways:

Gauss’s lemma provides, among many other things, a means for deciding whether or not 2 is a quadratic residue modulo and odd prime p.

Theorem 2.68 If p is an odd prime, then

(2.145)

Proof: By Gauss’s lemma, we know that if  is the number of least positive residues of the integers

is the number of least positive residues of the integers

that are greater than p/2, then  . Let

. Let  with

with  . Then 2k<p/2 if and only if k<p/4; so [p/4] of the integers

. Then 2k<p/2 if and only if k<p/4; so [p/4] of the integers  are less than p/2. So there are

are less than p/2. So there are  integers greater than p/2. Therefore, by Gauss’s lemma, we have

integers greater than p/2. Therefore, by Gauss’s lemma, we have

For the first equality, it suffices to show that

If  , then p = 8k+1 for some

, then p = 8k+1 for some  , from which

, from which

and

so the desired congruence holds for  . The cases for

. The cases for  are similar. This completes the proof for the first equality of the theorem. Note that the cases above yield

are similar. This completes the proof for the first equality of the theorem. Note that the cases above yield

which implies

This completes the second equality of the theorem.

Example 2.63 Evaluate  and

and  .

.

, since

, since  . Consequently, the quadratic congruence

. Consequently, the quadratic congruence  is solvable.

is solvable. , since

, since  . Consequently, the quadratic congruence

. Consequently, the quadratic congruence  is not solvable.

is not solvable.Using Lemma 2.3, Gauss proved the following theorem, which is one of the great results of mathematics:

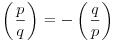

Theorem 2.69 (Quadratic reciprocity law) If p and q are distinct odd primes, then

if one of

if one of  ;

; if both

if both  .

.Remark 2.17 This theorem may be stated equivalently in the form

(2.146)

Proof: We first observe that, by Gauss’s lemma,  , where

, where  is the number of lattice points (x, y) (that is, pairs of integers) satisfying 0<x<q/2 and −q/2<px−qy<0. These inequalities give y<(px/q)+1/2<(p+1)/2. Hence, since y is an integer, we see

is the number of lattice points (x, y) (that is, pairs of integers) satisfying 0<x<q/2 and −q/2<px−qy<0. These inequalities give y<(px/q)+1/2<(p+1)/2. Hence, since y is an integer, we see  is the number of lattice points in the rectangle r defined by 0<x<q/2, 0<y<p/2, satisfying −q/2<px−qy<0 (see Figure 2.2). Similarly,

is the number of lattice points in the rectangle r defined by 0<x<q/2, 0<y<p/2, satisfying −q/2<px−qy<0 (see Figure 2.2). Similarly,  , where

, where  is the number of lattice points in r satisfying −p/2<qx−py<0. Now it suffices to prove that

is the number of lattice points in r satisfying −p/2<qx−py<0. Now it suffices to prove that  is even. But (p−1)(q−1)/4 is just the number of lattice points in r satisfying that

is even. But (p−1)(q−1)/4 is just the number of lattice points in r satisfying that  or

or  . The regions in r defined by these inequalities are disjoint and they contain the same number of lattice points, since the substitution

. The regions in r defined by these inequalities are disjoint and they contain the same number of lattice points, since the substitution

Figure 2.2 Proof of the quadratic reciprocity law

furnishes a one-to-one correspondence between them. The theorem follows.

Remark 2.18 The Quadratic Reciprocity Law was one of Gauss’s major contributions to mathematics. For those who consider number theory “the Queen of Mathematics,” this is one of the jewels in her crown. Since Gauss’s time, over 150 proofs of it have been published; Gauss himself published no less than six different proofs. Among the eminent mathematicians who contributed to the proofs are Cauchy, Jacobi, Dirichlet, Eisenstein, Kronecker, and Dedekind.

Combining all the above results for Legendre symbols, we get the following set of formulas for evaluating Legendre symbols:

(2.147)

(2.148)

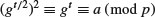

Example 2.64 Evaluate the Legendre symbol  .

.

|

by (2.150) |

|

by (2.151) |

|

by (2.152) |

|

by (2.149) |

|

by (2.153) |

It follows that the quadratic congruence  is soluble.

is soluble.

Example 2.65 Evaluate the Legendre symbol  .

.

|

by (2.151) |

|

by (2.153) |

|

by (2.154) |

|

by (2.150) |

|

by (2.151) |

|

by (2.152) |

|

by (2.153) |

It follows that the quadratic congruence  is not soluble.

is not soluble.

Gauss’s Quadratic Reciprocity Law enables us to evaluate the values of Legendre symbols  very quickly provided a is a prime or a product of primes, and p is an odd prime. However, when a is a composite, we must factor it into its prime factorization form in order to use Gauss’s quadratic reciprocity law. Unfortunately, there is no efficient algorithm so far for prime factorization (see Chapter 3 for more information). One way to overcome the difficulty of factoring a is to introduce the following Jacobi symbol (in honor of the German mathematician Carl Gustav Jacobi (1804–1851), which is a natural generalization of the Legendre symbol:

very quickly provided a is a prime or a product of primes, and p is an odd prime. However, when a is a composite, we must factor it into its prime factorization form in order to use Gauss’s quadratic reciprocity law. Unfortunately, there is no efficient algorithm so far for prime factorization (see Chapter 3 for more information). One way to overcome the difficulty of factoring a is to introduce the following Jacobi symbol (in honor of the German mathematician Carl Gustav Jacobi (1804–1851), which is a natural generalization of the Legendre symbol:

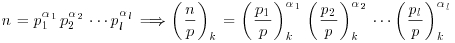

Definition 2.47 Let a be an integer and n>1 an odd positive integer. If  , then the Jacobi symbol,

, then the Jacobi symbol,  , is defined by

, is defined by

(2.155)

where  for

for  is the Legendre symbol for the odd prime pi. If n is an odd prime, the Jacobi symbol is just the Legendre symbol.

is the Legendre symbol for the odd prime pi. If n is an odd prime, the Jacobi symbol is just the Legendre symbol.

The Jacobi symbol has some similar properties to the Legendre symbol, as shown in the following theorem.

Theorem 2.70 Let m and n be any positive odd composites, and  . Then

. Then

, then

, then  ;

; ;

; , then

, then  ;

; ;

; ;

; , then

, then  .

.Remark 2.19 It should be noted that the Jacobi symbol  does not imply that a is a quadratic residue modulo n. Indeed a is a quadratic residue modulo n if and only if a is a quadratic residue modulo p for each prime divisor p of n. For example, the Jacobi symbol

does not imply that a is a quadratic residue modulo n. Indeed a is a quadratic residue modulo n if and only if a is a quadratic residue modulo p for each prime divisor p of n. For example, the Jacobi symbol  , but the quadratic congruence

, but the quadratic congruence  is actually not soluble. This is the significant difference between the Legendre symbol and the Jacobi symbol. However,

is actually not soluble. This is the significant difference between the Legendre symbol and the Jacobi symbol. However,  does imply that a is a quadratic nonresidue modulo n. For example, the Jacobi symbol

does imply that a is a quadratic nonresidue modulo n. For example, the Jacobi symbol

and so we can conclude that 6 is a quadratic nonresidue modulo 35. In short, we have

(2.156)

Combining all the above results for Jacobi symbols, we get the following set of formulas for evaluating Jacobi symbols:

(2.157)

Example 2.66 Evaluate the Jacobi symbol  .

.

|

by (2.160) |

|

by (2.162) |

|

by (2.163) |

|

by (2.149) |

|

by (2.158) |

|

by (2.161) |

It follows that the quadratic congruence  is not soluble.

is not soluble.

Example 2.67 Evaluate the Jacobi symbol  .

.

|

by (2.163) |

|

by (2.159) |

|

by (2.160) |

|

by (2.161) |

Although the Jacobi symbol  , we still cannot determine whether or not the quadratic congruence

, we still cannot determine whether or not the quadratic congruence  is soluble.

is soluble.

Remark 2.20 Jacobi symbols can be used to facilitate the calculation of Legendre symbols. In fact, Legendre symbols can be eventually calculated by Jacobi symbols. That is, the Legendre symbol can be calculated as if it were a Jacobi symbol. For example, consider the Legendre symbol  , where

, where  is not a prime (of course, 2999 is prime, otherwise, it would not be a Legendre symbol). To evaluate this Legendre symbol, we first regard it as a Jacobi symbol and evaluate it as if it were a Jacobi symbol (note that once it is regarded as a Jacobi symbol, it does not matter whether or not 335 is prime; it even does not matter whether or not 2999 is prime, but anyway, it is a Legendre symbol).

is not a prime (of course, 2999 is prime, otherwise, it would not be a Legendre symbol). To evaluate this Legendre symbol, we first regard it as a Jacobi symbol and evaluate it as if it were a Jacobi symbol (note that once it is regarded as a Jacobi symbol, it does not matter whether or not 335 is prime; it even does not matter whether or not 2999 is prime, but anyway, it is a Legendre symbol).

Since 2999 is prime,  is a Legendre symbol, and so 355 is a quadratic residue modulo 2999.

is a Legendre symbol, and so 355 is a quadratic residue modulo 2999.

Table 2.4 Jacobi Symbols for

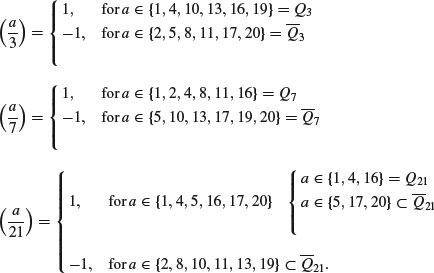

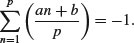

Example 2.68 In Table 2.4, we list the elements in  and their Jacobi symbols. Incidentally, exactly half of the Legendre and Jacobi symbols

and their Jacobi symbols. Incidentally, exactly half of the Legendre and Jacobi symbols  ,

,  and

and  are equal to 1 and half equal to −1. Also for those Jacobi symbols

are equal to 1 and half equal to −1. Also for those Jacobi symbols  , exactly half of the a’s are indeed quadratic residues, whereas the other half are not. (Note that a is a quadratic residue of 21 if and only if it is a quadratic residue of both 3 and 7.) That is,

, exactly half of the a’s are indeed quadratic residues, whereas the other half are not. (Note that a is a quadratic residue of 21 if and only if it is a quadratic residue of both 3 and 7.) That is,

browsing ---- left

******************

Problems for Section 2.4

and

and

primitive roots modulo n. (Note: Primitive roots are defined in Definition 2.49.)

primitive roots modulo n. (Note: Primitive roots are defined in Definition 2.49.)

. Show that there are no integer solutions in x for

. Show that there are no integer solutions in x for

is prime. Show that

is prime. Show that

, we have

, we have

,

,  ,

,  , then

, then

and

and  .

.

. Prove that if

. Prove that if  , and

, and  are not soluble, then

are not soluble, then  is soluble.

is soluble.

if and only if there are infinitely many b such that

if and only if there are infinitely many b such that

and p an odd prime, then

and p an odd prime, then

and p an odd prime, then

and p an odd prime, then

such that

such that

2.5 Primitive Roots

Definition 2.48 Let n be a positive integer and a an integer such that  . Then the order of a modulo n, denoted by ordn(a) or by ord(a, n), is the smallest integer r such that

. Then the order of a modulo n, denoted by ordn(a) or by ord(a, n), is the smallest integer r such that  .

.

Remark 2.21 The terminology “the order of a modulo n” is the modern algebraic term from group theory (the theory of groups, rings, and fields will be formally introduced in Section 2.1). The older terminology “a belongs to the exponent r” is the classical term from number theory as used by Gauss.

Example 2.69 In Table 2.5, values of  for

for  are given.

are given.

From Table 2.5, we get

Table 2.5 Values of  , for

, for

We list in the following theorem some useful properties of the order of an integer a modulo n.

Theorem 2.71 Let n be a positive integer,  , and r = ordn(a). Then

, and r = ordn(a). Then

, where m is a positive integer, then

, where m is a positive integer, then  ;

; ;

; if and only if

if and only if  ;

; are congruent modulo r;

are congruent modulo r; ;

; .

.Definition 2.49 Let n be a positive integer and a an integer such that  . If the order of an integer a modulo n is

. If the order of an integer a modulo n is  , that is,

, that is,  , then a is called a primitive root of n.

, then a is called a primitive root of n.

Example 2.70 Determine whether or not 7 is a primitive root of 45. First note that  . Now observe that

. Now observe that

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

. . |

Thus, ord45(7) = 12. However,  . That is,

. That is,  . Therefore, 7 is not a primitive root of 45.

. Therefore, 7 is not a primitive root of 45.

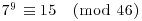

Example 2.71 Determine whether or not 7 is a primitive root of 46. First note that  . Now observe that

. Now observe that

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

. . |

Thus, ord46(7) = 22. Note also that  . That is,

. That is,  . Therefore 7 is a primitive root of 46.

. Therefore 7 is a primitive root of 46.

Theorem 2.72 (Primitive roots as residue system) Suppose  . If G is a primitive root modulo n, then the set of integers

. If G is a primitive root modulo n, then the set of integers  is a reduced system of residues modulo n.

is a reduced system of residues modulo n.

Example 2.72 Let n = 34. Then there are  primitive roots of 34, namely, 3, 5, 7, 11, 23, 27, 29, 31. Now let g = 5 such that

primitive roots of 34, namely, 3, 5, 7, 11, 23, 27, 29, 31. Now let g = 5 such that  . Then

. Then

which forms a reduced system of residues modulo 34. We can of course choose g = 23 such that  . Then we have

. Then we have

which again forms a reduced system of residues modulo 34.

Theorem 2.73 If p is a prime number, then there exist  (incongruent) primitive roots modulo p.

(incongruent) primitive roots modulo p.

Example 2.73 Let p = 47, then there are  primitive roots modulo 47, namely,

primitive roots modulo 47, namely,

Note that no method is known for predicting what will be the smallest primitive root of a given prime p, nor is there much known about the distribution of the  primitive roots among the least residues modulo p.

primitive roots among the least residues modulo p.

Corollary 2.10 If n has a primitive root, then there are  (incongruent) primitive roots modulo n.

(incongruent) primitive roots modulo n.

Example 2.74 Let n = 46, then there are  primitive roots modulo 46, namely,

primitive roots modulo 46, namely,

Note that not all moduli n have primitive roots; in Table 2.6 we give the smallest primitive root G for  that has primitive roots.

that has primitive roots.

Table 2.6 Primitive roots G modulo n (if any) for

The following theorem establishes conditions for moduli to have primitive roots:

Theorem 2.74 An integer n>1 has a primitive root modulo n if and only if

(2.164)

where p is an odd prime and  is a positive integer.

is a positive integer.

Corollary 2.11 If  with

with  , or

, or  with

with  or

or  , then there are no primitive roots modulo n.

, then there are no primitive roots modulo n.

Example 2.75 For n = 16 = 24, since it is of the form  with

with  , there are no primitive roots modulo 16.

, there are no primitive roots modulo 16.

Although we know which numbers possess primitive roots, it is not a simple matter to find these roots. Except for trial and error methods, very few general techniques are known. Artin in 1927 made the following conjecture (Rose [5]):

Conjecture 2.1 Let Na(x) be the number of primes less than x of which a is a primitive root, and suppose a is not a square and is not equal to −1, 0 or 1. Then

(2.165)

where a depends only on a.

Hooley in 1967 showed that if the extended Riemann Hypothesis is true then so is Artin’s conjecture. It is also interesting to note that before the age of computers Jacobi in 1839 listed all solutions  of the congruences

of the congruences  where

where  ,

,  , G is the least positive primitive root of p and p<1000.

, G is the least positive primitive root of p and p<1000.

Another very important problem concerning the primitive roots of p is the estimate of the lower bound of the least positive primitive root of p. Let p be a prime and g(p) the least positive primitive root of p. The Chinese mathematician Yuan Wang [3] showed in 1959 that

;

; , if the Generalized Riemann Hypothesis (GRH) is true.

, if the Generalized Riemann Hypothesis (GRH) is true.Wang’s second result was improved to  by Victor Shoup [4] in 1992.

by Victor Shoup [4] in 1992.

The concept of index of an integer modulo n was first introduced by Gauss in his Disquisitiones Arithmeticae. Given an integer n, if n has primitive root G, then the set

(2.166)

forms a reduced system of residues modulo n; G is a generator of the cyclic group of the reduced residues modulo n. (Clearly, the group  is cyclic if

is cyclic if  , for p odd prime and

, for p odd prime and  positive integer.) Hence, if

positive integer.) Hence, if  , then a can be expressed in the form:

, then a can be expressed in the form:

(2.167)

for a suitable K with  . This motivates our following definition, which is an analog of the real base logarithm function.

. This motivates our following definition, which is an analog of the real base logarithm function.

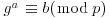

Definition 2.50 Let G be a primitive root of n. If  , then the smallest positive integer K such that

, then the smallest positive integer K such that  is called the index of a to the base G modulo n and is denoted by indg,n(a), or simply by indga.

is called the index of a to the base G modulo n and is denoted by indg,n(a), or simply by indga.

Clearly, by definition, we have

(2.168)

The function indga is sometimes called the discrete logarithm and is denoted by logga so that

(2.169)

Generally, the discrete logarithm is a computationally intractable problem; no efficient algorithm has been found for computing discrete logarithms and hence it has important applications in public key cryptography.

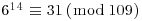

Theorem 2.75 (Index theorem) If G is a primitive root modulo n, then  if and only if

if and only if  .

.

Proof: Suppose that  . Then,

. Then,  for some integer K. Therefore,

for some integer K. Therefore,

The proof of the “only if” part of the theorem is left as an exercise.

The properties of the function indga are very similar to those of the conventional real base logarithm function, as the following theorems indicate:

Theorem 2.76 Let G be a primitive root modulo the prime p, and  . Then

. Then  if and only if

if and only if

(2.170)

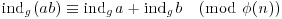

Theorem 2.77 Let n be a positive integer with primitive root G, and  . Then

. Then

;

; ;

; , if K is a positive integer.

, if K is a positive integer.Example 2.76 Compute the index of 15 base 6 modulo 109, that is,  . To find the index, we just successively perform the computation

. To find the index, we just successively perform the computation  for

for  until we find a suitable K such that

until we find a suitable K such that  :

:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

. . |

Since k = 20 is the smallest positive integer such that  ,

,  .

.

In what follows, we shall study the congruences of the form  , where n is an integer with primitive roots and

, where n is an integer with primitive roots and  . First of all, we present a definition, which is the generalization of quadratic residues.

. First of all, we present a definition, which is the generalization of quadratic residues.

Definition 2.51 Let a, n, and K be positive integers with  . Suppose

. Suppose  , then a is called a Kth (higher) power residue of n if there is an x such that

, then a is called a Kth (higher) power residue of n if there is an x such that

(2.171)

The set of all Kth (higher) power residues is denoted by K(k)n. If the congruence has no solution, then a is called a Kth (higher) power nonresidue of n. The set of such a is denoted by  . For example, K(9)126 would denote the set of the 9th power residues of 126, whereas

. For example, K(9)126 would denote the set of the 9th power residues of 126, whereas  the set of the 5th power nonresidue of 31.

the set of the 5th power nonresidue of 31.

(2.172)

If 2.171 is soluble, then it has exactly gcd(k,  (n)) incongruent solutions.

(n)) incongruent solutions.

Proof: Let x be a solution of  . Since

. Since  ,

,  . Then

. Then

Conversely, if  , then

, then  . Since

. Since  ,

,  , and hence

, and hence  because

because  must be an integer. Therefore, there are

must be an integer. Therefore, there are  incongruent solutions to

incongruent solutions to  and hence

and hence  incongruent solutions to

incongruent solutions to  .

.

If n is a prime number, say, p, then we have

Corollary 2.12 Suppose p is prime and  . Then a is a Kth power residue of p if and only if

. Then a is a Kth power residue of p if and only if

(2.173)

Example 2.77 Determine whether or not 5 is a sixth power of 31, that is, decide whether or not the congruence

has a solution. First of all, we compute

since 31 is prime. By Corollary 2.12, 5 is not a sixth power of 31. That is,  . However,

. However,

So, 5 is a seventh power of 31. That is,  .

.

Now let us introduce a new symbol  , the Kth power residue symbol, analogous to the Legendre symbol for quadratic residues.

, the Kth power residue symbol, analogous to the Legendre symbol for quadratic residues.

Definition 2.52 Let p be an odd prime, k>1,  and

and  . Then the symbol

. Then the symbol

(2.174)

is called the Kth power residue symbol modulo p, where  represents the absolute smallest residue of

represents the absolute smallest residue of  modulo p. (The complete set of the absolute smallest residues modulo p are:

modulo p. (The complete set of the absolute smallest residues modulo p are:  ).

).

Theorem 2.79 Let  be the Kth power residue symbol. Then

be the Kth power residue symbol. Then

;

; ;

; ;

; ;

; ;

; .

.Example 2.78 Let p = 19, k = 3 and q = 6. Then

All the above congruences are modular 19.

Problems for Section 2.5

if and only if

if and only if  .

. form a reduced residue system modulo p if and only if

form a reduced residue system modulo p if and only if  .

. are primitive roots modulo an odd prime p, then

are primitive roots modulo an odd prime p, then  is not a primitive root modulo p.

is not a primitive root modulo p.

, but

, but  for every proper divisor d of n−1, then n is a prime.

for every proper divisor d of n−1, then n is a prime.

.

.

.

.2.6 Elliptic Curves

The study of elliptic curves is intimately connected with the the study of Diophantine equations. The theory of Diophantine equations is a branch of number theory which deals with the solution of polynomial equations in either integers or rational numbers. As a solvable polynomial equation always has a corresponding geometrical diagram (e.g., curves or even surfaces). thus to find the integer or rational solution to a polynomial equation is equivalent to find the integer or rational points on the corresponding geometrical diagram, this leads naturally to Diophantine geometry, a subject dealing with the integer or rational points on curves or surfaces represented by polynomial equations. For example, in analytic geometry, the linear equation

(2.175)

represents a straight line. The points (x, y) in the plane whose coordinates x and y are integers are called lattice points. Solving the linear equation in integers is therefore equivalent to determining those lattice points that lie on the line; The integer points on this line give the solutions to the linear Diophantine equation ax+by+c = 0. The general form of the integral solutions for the equation shows that if (x0, y0) is a solution, then there are lattice points on the line:

(2.176)

If the polynomial equation is

(2.177)

then its associate algebraic curve is the unit circle. The solution (x, y) for which x and y are rational correspond to the Pythagorean triples x2+y2 = 1. In general, a polynomial f(x, y) of degree 2

(2.178)

gives either an ellipse, a parabola, or a hyperbola, depending on the values of the coefficients. If f(x, y) is a cubic polynomial in (x, y), then the locus of points satisfying f(x, y) = 0 is a cubic curve. A general cubic equation in two variables is of the form

(2.179)

Again, we are only interested in the integer solutions of the Diophantine equations, or equivalently, the integer points on the curves of the equations.

The above discussions lead us very naturally to Diophantine geometry, a subject dealing with the integer or rational points on algebraic curves or even surfaces of Diophantine equations (a straight line is a special case of algebraic curves).

Definition 2.53 A rational number, as everybody knows, is a quotient of two integers. A point in the (x, y)-plane is called a rational point if both its coordinates are rational numbers. A line is a rational line if the equation of the line can be written with rational numbers; that is, the equation is of the form

(2.180)

where a, b, c are rational numbers.

Definition 2.54 Let

(2.181)

be a conic. Then the conic is rational if we can write its equation with rational numbers.

We have already noted that the point of intersection of two rational lines is rational point. But what about the intersection of a rational line with a rational conic? Will it be true that the points of intersection are rational? In general, they are not. In fact, the two points of intersection are rational if and only if the roots of the quadratic equation are rational. However, if one of the points is rational, then so is the other.

There is a very general method to test, in a finite number of steps, whether or not a given rational conic has a rational point, due to Legendre. The method consists of determining whether a certain congruence can be satisfied.

Theorem 2.80 (Legendre) For the Diophantine equation

(2.182)

there is an integer n, depending on a, b, c, such that the equation has a solution in integers, not all zero, if and only if the congruence

(2.183)

has a solution in integers relatively prime to n.

An elliptic curve is an algebraic curve given by a cubic Diophantine equation

(2.184)

More general cubics in x and y can be reduced to this form, known as Weierstrass normal form, by rational transformations.

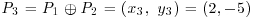

Example 2.79 Two examples of elliptic curves are shown in Figure 2.3 (from left to right). The graph on the left is the graph of a single equation, namely E1 : y2 = x3 - 4x + 2; even though it breaks apart into two pieces, we refer to it as a single curve. The graph on the right is given by the equation E2 : y2 = x3 - 3x + 3. Note that an elliptic curve is not an ellipse; a more accurate name for an elliptic curve, in terms of algebraic geometry, is an Abelian variety of dimension one. It should also be noted that quadratic polynomial equations are fairly well understood by mathematicians today, but cubic equations still pose enough difficulties to be topics of current research.

Figure 2.3 Two examples of elliptic curves

Definition 2.55 An elliptic curve E : y2 = x3+ax+b is called nonsingular if its discriminant

(2.185)

Remark 2.22 By elliptic curve, we always mean that the cubic curve is nonsingular. A cubic curve, such as y2 = x3−3x+2 for which  , is actually not an elliptic curve; such a cubic curve with

, is actually not an elliptic curve; such a cubic curve with  is called a singular curve. It can be shown that a cubic curve E : y2 = x3+ax+b is singular if and only if

is called a singular curve. It can be shown that a cubic curve E : y2 = x3+ax+b is singular if and only if  .

.

Definition 2.56 Let  be a field. Then the characteristic of the field

be a field. Then the characteristic of the field  is 0 if

is 0 if

is never equal to 0 for any n>1. Otherwise, the characteristicof the field  is the least positive integer n such that

is the least positive integer n such that

Example 2.80 The fields  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  all have characteristic 0, whereas the field

all have characteristic 0, whereas the field  is of characteristic p, where p is prime.

is of characteristic p, where p is prime.

Definition 2.57 Let  be a field (either the field

be a field (either the field  ,

,  ,

,  , or the finite field

, or the finite field  with

with  elements), and x3+ax+b with

elements), and x3+ax+b with  be a cubic polynomial. Then

be a cubic polynomial. Then

is a field of characteristic

is a field of characteristic  , then an elliptic curve over

, then an elliptic curve over  is the set of points (x, y) with

is the set of points (x, y) with  that satisfy the following cubic Diophantine equation:

that satisfy the following cubic Diophantine equation:(2.186)

, called the point at infinity.

, called the point at infinity. is a field of characteristic 2, then an elliptic curve over

is a field of characteristic 2, then an elliptic curve over  is the set of points (x, y) with

is the set of points (x, y) with  that satisfy one of the following cubic Diophantine equations:

that satisfy one of the following cubic Diophantine equations:(2.187)

.

. is a field of characteristic 3, then an elliptic curve over