Organized Crime and New Participants

The Internet is not a well-organized market dominated by fixed social norms. It is wide open and more anarchic than orderly. Generally, users are free to lie, create the foundations of illicit relationships, and often remain anonymous. The Internet is the software-hardware backbone of good things (e.g., scientific and scholarly collaboration) and bad things (e.g., conspiracies and antitrust collusion). Traditional organized crime arose before the invention of the Internet, and some have argued that the use of the Internet generally has resulted in an enhanced facilitation of criminal activities, for example, the Internet fosters cybercrime committed collectively whether globally and/or locally. However, it might not have created new groups of organized criminals as per the traditional hierarchical model (McCusker 2006, 273), but it has birthed transnational organized economic crime using legitimate and illegitimate pathways, for example:

• Transnational high tech organizations (e.g., Google, Twitter, Facebook) provide virtual meet-and-greet venues. These platforms do not conduct due diligence on their users; they do not audit and investigate the claims and aims of the users. Their collective expanse is a hybrid of wasteland and fecundity, for better and worse.

• PayPal and other fintech services create new opportunities to conduct licit and illicit financial flows among originators, intermediaries and correspondents, and beneficiaries. The natural persons directing, controlling, and benefiting from these opportunistic pathways are protected from transparency, disclosure, and accountability, often by rule of law.

Social media empowered through the Internet offers a fairly safe and efficient means for black and gray market participants to hook up and conspire, assuming the use of counter-surveillance software and hardware to confuse, mislead, and distract law enforcement and intelligence agencies. However, deeper, more clandestine pathways are available to obtain tools to create and exploit black and gray markets.

As no highly profitable, infamous crime is accomplished alone, collusion is necessary. Networks and associations of individuals are necessary to effectuate the processes of finding customers, providing goods and services, obtaining payments, and so on. This occurs in legitimate and illegitimate enterprises. However, the illicit nature of organized crime demands more circumspection than legitimate businesses that may advertise and promote liberally. Significantly, to a great extent, organized crime operates like a network economy (Wainwright 2016, 175): knowledge of, trust in, and anonymity of suppliers and customers outside of the network is necessary to avoid the web of law enforcement.

Analogous to legitimate businesses organized crime deploys and leverages high tech, including exploiting, for example, the capacities of the TOR (the onion router) browser to conceal the locations (Internet protocol addresses) of persons using the dark web’s otherwise inaccessible websites (see Marker 2019). Anonymity breeds fraud and corruption as much as unbridled power and unchecked discretion foster abuse and lack of accountability, other things being equal. Thus, the inherent unaccountability and leverageable socioeconomic power from unchecked, unmonitored endto-end encryption tend to corrupt, with the dark web, a key set of covert pathways to organize, commit, and conceal criminal activities.

The dark web is comprised of thousands of websites that can only be accessed with special browser software (e.g., Tor), facilitating illicit activity including transnational money laundering (Quintero 2017). Through anonymity, encryption, and the use of virtual currencies, users connecting with likeminded others to exchange goods, including child pornography, for monetary value (e.g., bitcoins) endeavor to act under the radar of law enforcement and intelligence agency surveillance. These conditions facilitate wrongful acts and their concealment, resulting in the expansion of successful opportunities for transnational organized crime. In brief, cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin and the dark web’s menu of products and services may comprise a vehicle and pathway for fraud, arms dealing, and terrorism by organized crime (Georgetown Security Studies Review 2018).

In brief, the dark web is a virtual convergence point that functions as broker for buyers and sellers of illicit goods such as drugs, firearms, and cybercrime tools (e.g., malware) (Europol 2018). Software tools such as Tor and 12P would be deployed to access and exploit the dark web’s goods and services offerings under cover of encryption. Additionally, the use of virtual private networks (VPNs) could be used to hide the fact that the user is deploying tools such as Tor or 12P; without a VPN, the user’s internet service provider (ISP) would be aware that the user is using these tools. Together, tools such as Tor or 12P and working through a VPN empower both legitimate users seeking privacy and illegitimate users seeking to procure or sell illicit goods and services (Holden n.d.). Superficially, the market is neutral, neither necessarily white nor necessarily black/gray.

Thus, the dark web creates a big, covert store of information (a virtual mall) wherein illicit goods and services may be negotiated for purchase and sale with a level of anonymity that cannot be obtained through traditional worldwide web browsing inside the Internet. Organized criminal activity is facilitated through this computed-based intransparency, facilitating the development, persistence, and growth of gig-style entrepreneurial and clandestine networks—an encrypt-able “Uber” for illicit conduct.

The dark web fosters an underground virtual opportunistic economy where information can be obtained about potential accomplices and means and methods may be secured (Security Intelligence 2016). Outsourcing of key and necessary skills such as coding for cybercrime and fraud is accomplished efficiently and effectively through the dark web, empowering otherwise small groups or cells of criminal actors to leverage the severity and social harms of their actions and broaden their range of victims (e.g., banks through hacker coding and identity theft): the art of cyber-facilitated fraud and theft as a modern transnational gig.

Some salient observations:

• Criminal transactions using the computer characterize global networks and gigs. The computer bridges the physical separation and gives rise to activities that seem legit but are not (e.g., high quality forgeries and faked websites).

• The dark web, which exists beyond the searchable Internet used by mainstream scholars, analysts, and other users, comprises a criminogenic virtual venue wherein secrecy allows for shadowy conduct—ideal for gray and black markets.

• Tools for mitigating the risks presented by the dark web are most effective when (from the perspective of the United States) composed of partnerships of international, federal, state, local, tribal, and private sector organizations in an information sharing environment.

• Activities conducted through the dark web are inherently covert, in a sense, but they are not ipso facto illicit. Individuals may use the dark web to conduct white market transactions (e.g., joining social clubs) (Guccione 2020).

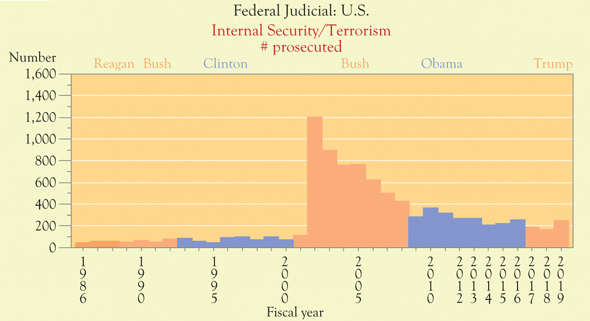

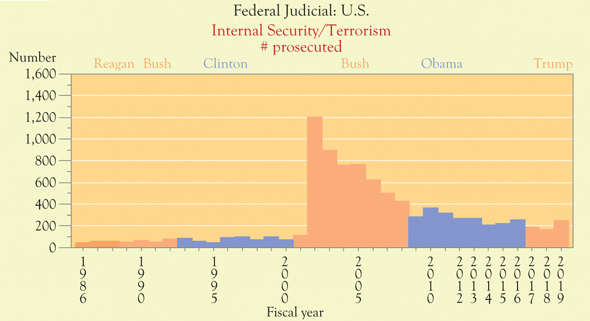

Cybercrime and security intelligence have been given significant attention at official agencies since September 11, 2001. Law enforcement agencies such as the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation and intelligence offices such as the U.S. Director of National Intelligence have combined forces in formal and informal partnerships with other key entities in the public and private sectors on a worldwide basis to corral the threat of transnational organized economic crimes committed through global webs of entrepreneurs using computer-based tools to communicate with one another, form alliances, obtain criminally others’ identities and properties, and get away with these collective acts of theft, deceit, and, in some cases, terrorism support. However, the success of these official partnerships is unclear. See Figure 16.1 below.

The pattern seems familiar: officially pump up the threat level, using mass media and other experts, scholars, and analysts, to demand counter-intelligence and risk mitigation strategies; obtain oodles of financial resources and funding from the governments; conduct widespread electronic surveillance and deployment of other investigative and intelligence tools (e.g., informants paid by law enforcement agencies) and/or elements of the intelligence community (e.g., the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency); prosecute criminal activities, where necessary. In brief, the trend of prosecutions indicates, consistent with the boosting of the threat of traditional organized crime, that the level of threat is not commensurate with criminal investigations and public prosecutions.

Figure 16.1 Federal Internet security and terrorism prosecutions, fiscal years 1986–2019

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University (TRACfed)

In a sense, the threat is invisible (which is not equivalent to denying that victims’ identities are stolen, corporate treasuries and offerings of products and services are not subjected to denial of service attacks, and so on). Moreover, during these high times characterized by extensive signals intelligence and surveillance webs, it seems a wonder that anyone gets away with anything.