In December 1905 Clyde William Fitch, then America’s most famous living dramatist, knocked on the door of 884 Park Avenue, the novelist Edith Wharton’s New York residence. Wharton’s first best seller The House of Mirth had just appeared, and Fitch, a flamboyant and prolific playwright rumored to have enjoyed “relations” with Oscar Wilde, asked if he might persuade her to collaborate on a stage adaptation of her new novel. She accepted the offer, though with reservations.

Wharton had tried to win over theatergoers with original plays before. But she could never descend low enough for the average audience and had rebuffed a friend’s advice that if she wanted a hit play, she should consider the century-old costumes and “society gags” that sold at the box office. Many illustrious fiction writers such as herself had taken their turn “on the boards” from the 1880s to the early 1900s—Henry James, William Dean Howells, Mark Twain, Bret Harte, Hamlin Garland, Mary Austin, and Jack London, among others—none of them successfully. “Forget not,” Henry James cautioned would-be playwrights, “that you write for the stupid.”

Leaving the Savoy Theatre in Herald Square after the New York premiere of The House of Mirth on October 22, 1906, Wharton remarked to her escort, William Dean Howells, “What the American public always wants is a tragedy with a happy ending.” And after the play received several poor reviews, she admitted, “I now doubt if that kind of play, with a ‘sad ending,’ and a negative hero, could ever get a hearing from an American audience.” Nearly three decades later, Wharton agreed to another collaboration, this time with playwright Zoë Akins, based on Wharton’s dolorous novella The Old Maid (1924). The play was a resounding success, and it beat out Lillian Hellman’s thematically parallel The Children’s Hour and Clifford Odets’s Awake and Sing! for the 1935 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. By then, even Wharton’s play was hotly contested as not original or experimental enough for the award, however, and opponents to the decision consequently founded the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award.

The following year, 1936, Eugene O’Neill, having already won three Pulitzers in the 1920s, emerged as the only American dramatist to date to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. It was an honor, he told the Swedish Academy, that spoke to the evolution of American drama as a whole: “This highest of distinctions is all the more grateful to me because I feel so deeply that it is not only my work that is being honored, but the work of all of my colleagues in America—that this Nobel Prize is a symbol of the recognition by Europe of the coming-of-age of the American theatre … worthy at last to claim kinship with the modern drama of Europe, from which our original inspiration so surely derives.”

Whatever one’s prejudice about the Nobel or the Pulitzer, and whatever one’s opinion of O’Neill’s tragic vision, by the 1930s, everyone agreed: American plays like O’Neill’s, with “sad endings and negative heroes,” even while faced with daunting competition from the lighter forms of entertainment amply provided by the Hollywood studio system and the commercial theater, had at last found their hearing.

![]()

ACT I: The Ghosts at the Stage Door

It is impossible to act in the American play unless we go back and see that the American play really starts with O’Neill. But in order to get to O’Neill, you have to know what was before him. … Before O’Neill in this country, the play was for business, for success, for the star who brought in money, for its fashionableness to an audience. The theater was nothing more, and not thought of as anything more, than a place of amusement.

—STELLA ADLER, 2010

Before Eugene O’Neill … there was a wasteland. … Two centuries of junk.

—GORE VIDAL, 1959

The Treasures of Monte Cristo

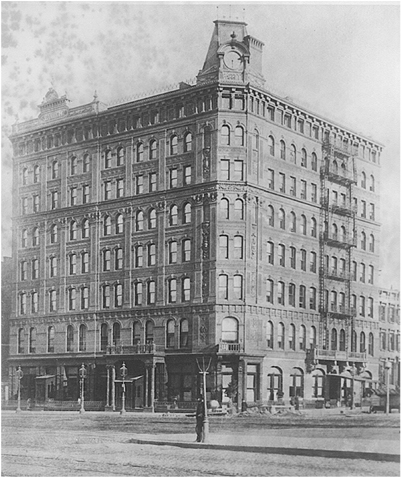

MARY ELLEN “ELLA” QUINLAN O’NEILL gave birth to her third and last child, Eugene, at the Barrett House hotel in Manhattan on October 16, 1888. Situated on the northeast corner of Broadway and Forty-Third Street, the Barrett House loomed at the intersection of what would become Times Square, the theatrical center of the world. Ella’s hotel room had a corner view of the neighborhood where her newborn’s name would burn brightly on electric marquees as a heady draw for the theatergoing public. Two days after his birth, Eugene was swept away with his family on the first of many national tours with his father, the matinee idol James O’Neill.

One of the most celebrated actors of his day and a natural successor to the great Shakespearean actor Edwin Booth, James was born in 1845, the son of Edward and Mary O’Neill, Irish immigrants of the peasant class from County Kilkenny. In 1850, Edward had emigrated to Buffalo, New York, with his wife and their eight children to escape the devastation of the potato famine. (James was the seventh child, and his sister Margaret, born in Buffalo in 1851, made nine.) The transatlantic journey was so harrowing that James rarely spoke of it as an adult. A few years later, in the mid-1850s, Edward O’Neill returned to Ireland after his eldest son, Richard, died, leaving the rest of the family to fend for themselves. Edward himself died of arsenic poisoning in Ireland six years after his departure, most likely a suicide.1

The Barrett House, O’Neill’s birthplace, at Broadway and Forty-Third Street, later Times Square. O’Neill responded to the friend who sent this image to him as a present that the man leaning against the lamppost obviously “had a bun on” (that is, he was drunk).

(COURTESY OF SHEAFFER-O’NEILL COLLECTION, LINDA LEAR CENTER FOR SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES, CONNECTICUT COLLEGE, NEW LONDON)

![]()

James O’Neill, at a mere ten years old, was thus compelled to help support his family by working grueling twelve-hour shifts making files at a machine shop. “A dirty barn of a place,” James Tyrone (O’Neill) remembers the shop in his son’s autobiographical play Long Day’s Journey Into Night, “where rain dripped through the roof, where you roasted in summer, and there was no stove in winter, and your hands got numb with cold, where the only light came through two small filthy windows, so on grey days I’d have to sit bent over with my eyes almost touching the files in order to see! … And what do you think I got for it? Fifty cents a week! It’s the truth! Fifty cents a week!” (CP3, 807). By 1858, the O’Neills had relocated to Cincinnati, Ohio, where they were largely supported by James’s older sister Josephine, who’d fortuitously married a prosperous Ohio saloonkeeper. It was in Cincinnati that James discovered his talent for acting at age twenty, when he made his debut in 1865 during the final days of the Civil War at Cincinnati’s National Theatre and rapidly gained a reputation as a dashing leading man.

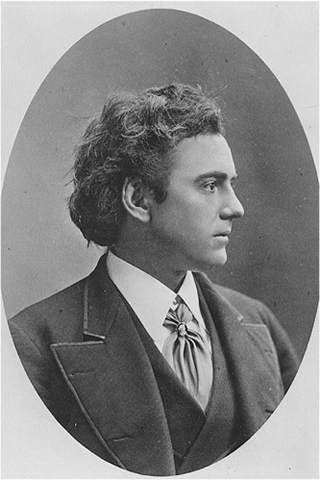

James O’Neill, 1869.

(COURTESY OF THE HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY THEATRE COLLECTION, CAMBRIDGE, MASS.)

![]()

The reigning “queen of actresses,” Adelaide Neilson, a British performer whose Juliet was thought to be the finest of all time, was once asked which Romeo among the many she’d played opposite was best. Neilson replied brusquely, “A little Irishman named O’Neill.”2 In 1872, James found himself onstage with Edwin Booth, “the greatest actor of his day or any other,” James Tyrone boasts in Long Day’s Journey (CP3, 809). Booth, the brother of Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, and James played Othello at McVicker’s Theatre in Chicago, each night alternating the roles of Iago and Othello. During one performance, while waiting for his cue in the wings, Booth remarked, “That young man is playing [Othello] better than I ever did.”3 This single evening, after James had been informed of Booth’s tribute to him, marked the high point of his acting career, perhaps of his entire life. James would never again experience such a genuine surge of professional gratification.

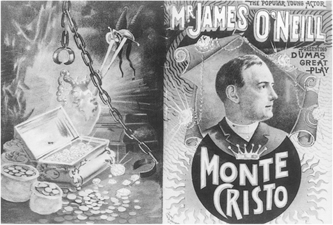

On February 12, 1883, James accepted a role at New York’s Booth Theatre that would thrust him into the national limelight, though he would notoriously become trapped by its very popularity: Edmund Dantès in Charles Fechter’s 1870 stage adaptation of Alexandre Dumas’s novel The Count of Monte Cristo, the title of which, though it’s offen forgotten, Fechter had reduced to the more straightforward Monte Cristo.

James had played Edmund Dantès back in Chicago on April 21, 1875, while a stock actor at Hooley’s Theatre, and the reviews for that performance had been excellent. The Spirit of the Times newspaper, however, predicted of the new Booth Theatre production that “Monte Cristo will not run very long.” James had been prevented by heavy snowfall from attending most of the rehearsals, and consequently he’d only had a few days to learn his part. John Stetson, the owner of the Globe Theatre in Boston, ignored the bad notices and kept the production going. Fechter’s widow was brought in as a consultant, and she worked enough magic to make it a hit.4

The legendary character Edmund Dantès is an upright sailor wrongly accused of treason against the king of France and cast into a dungeon at the Château d’If off the coast of Marseilles. His imprisonment clears the way for the villain Fernand to gain Edmund’s betrothed, the Catalan Mercédès (a name that James, who spoke some French, liked to enunciate affectedly with a rolling “r”).5 After languishing in prison for eighteen years, Edmund makes his getaway with the help of his dying cellmate, friend, and benefactor Abbé Faria. Eventually, he reclaims Mercédès and a son, Albert, who had been conceived before Dantès’s imprisonment (without, as the saying goes, the benefit of clergy). Dantès doesn’t have many lines; most of the dialogue is reserved for the play’s villains pacing about conspiring against one another. But the spectacular prison escape is far and away the most defining scene of James’s career: “The moon breaks out, lighting up a projecting rock,” the stage directions specify, then “Edmund rises from the sea, he is dripping, a knife in his hand, some shreds of sack adhering to it.” He stands up on the stone pedestal and shouts exultantly to the heavens, “The world is mine!” James would enact this climactic scene to as many as six thousand audiences, thus branding his acting reputation forever.6

Monte Cristo playbill.

(COURTESY OF SHEAFFER-O’NEILL COLLECTION, LINDA LEAR CENTER FOR SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES, CONNECTICUT COLLEGE, NEW LONDON)

![]()

Far more relevant to James’s actual life, however, are the lines that precede the heroic declaration: “Saved! Mine, the treasures of Monte Cristo! The world is mine!”7 “The treasures of Monte Cristo” refer to a hidden fortune on a deserted island that Faria bequeaths to Dantès before dying in prison. After his daring escape, Dantès spends years traveling the world spending Faria’s money lavishly before, apparently as an afterthought, returning to Mercédès. More than about love, then, Monte Cristo is about money, and James soon decided to acquire his own “treasure of Monte Cristo”: the rights to the Fechter script for $2,000. With sole proprietorship of the play as of the 1885–86 season, James O’Neill would perform the role to packed houses for almost thirty years, earning him a profit of nearly forty thousand a year. Like Edmund Dantès, James had escaped from a prison of his own—the prison of poverty. And both men were spared horrible fates by dint of their talent, honesty, and charisma.8

Charles Fechter’s Monte Cristo is saturated with doses of moustache twirling by evildoers and moral posturing by good-guy swashbucklers. One line from Edmund Dantès neatly sums up the play’s complexity: “Sooner or later believe me, the honest man will meet his reward and the wicked be punished.”9 Those who surrender an afternoon to Fechter’s abysmal dialogue will discover their minds drifting off and returning back to a single question: Why would theatergoers choose to see this grossly melodramatic play night after night, year after year? The script was considered just as hackneyed in those days, and the question was the same then as it is today. “The answer, of course, was my father,” Eugene O’Neill explained toward the end of his own career. “He had a genuine romantic Irish personality—looks, voice, and stage presence—and he loved the part. … Audiences came to see James O’Neill in Monte Cristo, not Monte Cristo.”10

O’Neill’s vocal contempt for his father’s play once he’d grown old enough to have such opinions would be echoed by him years later in a speech by the guileless Marco Polo in the historical satire Marco Millions (1928). At one point, Marco repeats the lackluster word “good” six times to emphasize his bourgeois tastes: “There’s nothing better than to sit down in a good seat at a good play after a good day’s work in which you know you’ve accomplished something, and after you’ve had a good dinner, and just take it easy and enjoy a good wholesome thrill or a good laugh and get your mind off serious things until it’s time to go to bed” (CP2, 431). Shakespeare similarly derided plays designed “to ease the anguish of a torturing hour” in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, while in O’Neill’s earliest satire, Now I Ask You (1916), Lucy Ashleigh, a pretentious adorer of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler (1890), argues against attending vaudeville shows because “those productions were concocted with an eye for the comfort of the Tired Business Man” (CP1, 451).

Some of the earliest words O’Neill remembered his father uttering were “The theater is dying.” James in fact came to regard his good fortune as a “curse” that had barred him from true theatrical greatness. Although O’Neill later believed that he alone had been told of this family curse, James had been quite open to the press about it. In 1901, for instance, a reporter ran into him in Broadway Alley and asked about his future plans. “My private secretary informs me that I have played Dantes four thousand times,” James said. “I have struggled to elaborate my repertoire, but what can a man do when his greatest measure of success seems to lie in a familiar rut? When a treadmill is grinding out big profits, you know, it is rather difficult to step from it.”11

In fact, the curse of Monte Cristo had bedeviled the actor as far back as 1885, before he’d even bought the rights to the Fechter script. Just after his second son Edmund’s death, when James was at his most emotionally fragile, he was approached by a meddlesome reporter in a Chicago wine bar and, with his guard carelessly down, confided everything. The article offers a detailed exposition on the “improvidence” of actors like James, whose “great promise has never been realized” and recounts James’s wistful, wine-soaked grief for his “early days,” when “Jimmy O’Neill” “performed Iago to Booth’s Othello with an aptness and clearness of conception that all but eclipsed the star himself.” “And yet, in spite of all his successes in the ‘legitimate,’” the reporter went on, “he forsook the higher walks of the drama, adopting melodramatic roles which are ephemeral as the day when compared with the true art in which he had given such promise.”12 For the remainder of his life, James lamented his choice of profits over the nobler pursuits of the stage. “That’s what caused me to make up my mind that they would never get me,” O’Neill said after learning of this. “I determined then that I would never sell out.”13

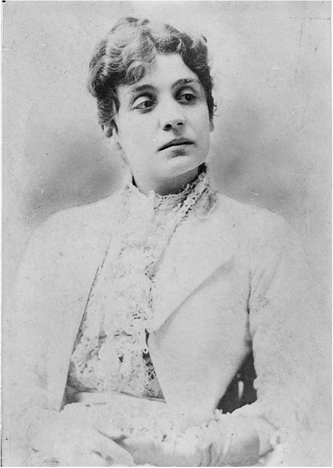

Ella O’Neill, like her husband, James, was born into a first-generation Irish home. Her parents, Thomas and Bridget Quinlan, were also famine refugees, but Thomas thrived in the United States as a tobacco and liquor merchant in Cleveland, Ohio. Ella met the impossibly handsome James, who was twelve years her senior and by then a sought-after bachelor, in 1872 through her father, Thomas, whom James had befriended at the Quinlans’ liquor shop, a popular hangout for performers within a short walk of the city’s Academy of Music. Ella and James were married five years later and had three sons together—James Jr. in 1878, Edmund Burke in 1883, and Eugene Gladstone in 1888. (Charles Fechter, not incidentally, had anglicized Dumas’s hero’s name from “Edmond” to “Edmund.” James’s older brother, named Edward after their father, had died in battle during the Civil War. But James didn’t choose to name his first two sons after his father or his brother, whose veteran’s pension had sustained their mother Mary. Rather, he named them in effect after his dual personae, offstage and on: James and Edmund.)14

On March 4, 1885, at four o’clock in the morning, Edmund, only eighteen months, died.15 The death of a child is an unimaginable horror for any parent, of course, but the cause of his death was especially shocking. The O’Neills had left Edmund and Jamie, as they called their firstborn, in New York under the care of Ella’s mother, Bridget, while James was performing in Colorado. Jamie contracted measles in their absence, and the obstreperous six-year-old was under his grandmother’s strict orders not to come in contact with his little brother. He went into the child’s bedroom anyway, and only a few days later Edmund succumbed to the disease. Ella returned to New York by train straight away while James stayed on to finish the tour. “The vast audience,” reported the Denver Tribune-Republican the night Ella departed, “did not know that James O’Neill … was heartbroken. It did not know that at that moment his little child lay dead in far distant New York, and that the agonized mother had just taken a tearful farewell of him to attend the burial of the little one. It laughed and clapped its hands and paid no thought but to the actor’s genius, and dreamed not of the inward weeping that was drowning his heart.”16

O’Neill became convinced in the years to follow that his mother never forgave his older brother Jim, as he called him, for infecting Edmund; and he himself suffered from a tormenting mixture of survivor’s guilt and death envy, later naming his autobiographical character in Long Day’s Journey “Edmund” and the dead child “Eugene.” The reversal of names in the play appears to have an even deeper symbolic meaning for the mother, Mary Cavan Tyrone, who makes clear that she gave birth to her third son to replace the deceased Eugene, and only at the insistence of her husband James (CP3, 766). Hence O’Neill proposes that his birth was no more than a mistake made out of desperation and that his existence in her eyes was a bedeviling reminder of her guilt over Edmund. It’s no wonder, then, that O’Neill later wrote down, without explanation and despite the fact that his mother was a practicing Catholic, that he’d been born in the wake of “a series of brought-on abortions.”17 “I knew I’d proved by the way I’d left Eugene [Edmund] that I wasn’t worthy to have another baby,” Mary Tyrone says to James while high on morphine, “and that God would punish me if I did. I never should have borne Edmund [Eugene]” (CP3, 766).

Mary Ellen “Ella” Quinlan O’Neill.

(COURTESY OF SHEAFFER-O’NEILL COLLECTION, LINDA LEAR CENTER FOR SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES, CONNECTICUT COLLEGE, NEW LONDON)

![]()

Worse still, perhaps, a hotel doctor prescribed Ella O’Neill morphine for the intolerable pain of giving birth to Eugene, an eleven-pound baby, thus precipitating a drug addiction that would last for well over two decades and haunt Ella and the O’Neill men to all of their deaths. This was the guilt-ridden, blame-laden family substructure that O’Neill would lay bare in Long Day’s Journey Into Night, a play, he wrote, “of old sorrow, written in tears and blood … with deep pity and understanding and forgiveness for all the four haunted Tyrones” (CP3, 714).

O’Neill toured with his parents around the American theater circuit for the first seven years of his life. “Usually a child has a regular, fixed home,” he said decades later, “but you might say I started in as a trouper. I knew only actors and the stage. My mother nursed me in the wings and in dressing rooms.”18 But like any average American lad, one of his earliest memories involved … what else? Cowboys and Indians. Most small boys from the Northeast became enraptured by the romantic lure of the Wild West by reading dime novels and magazines. O’Neill’s father brought him right to the source.

James O’Neill’s advance man, George C. Tyler, marveled at the storybook figures his boss fraternized with across the West. On any given night, Tyler said, he would find James in a saloon chatting with “the biggest poker player in the United States, or Buffalo Bill Cody or somebody like that—the biggest guns in any walk of life were a natural part of his background.”19 Indian-related violence in the Montana Territory had abated after the Great Sioux War (1876–77), and James, the prosperous showman and Civil War veteran Nate Salsbury, and Colonel William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody together held lucrative shares in a Montana ranch called the Milner Cattle Company. So the three men communed together at barrooms whenever they chanced to find themselves performing in the same Western town.

In his adult years, O’Neill calculated that he’d been around two years old and near death from typhoid in a Chicago hotel room when Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and other Sioux “hostiles” from the Dakota Territory gathered around his sickbed. He remembered feather headdresses and blankets draped across imposing, longhaired heads and “big brown” bodies. One of James O’Neill’s associates had indeed assembled a troupe of Sioux performers from William Cody’s Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show to offer the child some respite from the stomach cramps, headaches, and soaring temperatures with which typhoid assails its victims. O’Neill couldn’t recollect the words spoken, though he remembered the visits took place over the course of a month. Whatever was said, this memory—maybe his earliest—“left him with the low-down on Custer,” he told a friend in 1946, “and an acute sympathy for the redman.”20

This makes for a great story. But Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse weren’t there at O’Neill’s sickbed in Chicago. Sitting Bull had performed only one season for William Cody, and that was four years before O’Neill was born. It’s unlikely that Crazy Horse would have submitted to the demeaning behavior expected of Cody’s performers; but in any case, he couldn’t have. Crazy Horse was killed by a prison guard in 1877 after his pyrrhic victory at Little Big Horn. And by the time the O’Neills arrived in Chicago in the late spring of 1891, when Eugene was two and a half, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was on tour in Europe. Cody wouldn’t play Chicago again until 1893 at the famed World’s Columbian Exposition, better known as the great Chicago World’s Fair, commemorating the four hundredth anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s discovery of the New World.21 With these facts in mind, the only plausible story is nearly as good as the one O’Neill recalled.

The Chicago run of James’s romantic drama Fontanelle, a welcome thirty-week break from Monte Cristo, opened on March 12, 1893, after which the O’Neill family spent the last week of March “resting” in the Second City before traveling eastward on Easter Sunday, April 2, 1893.22 Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, whose performers had been in town throughout March preparing for their six-month engagement, opened the following day, April 3. (Cody’s act was deemed too mawkish a billing for the official grounds, so the show was performed just outside the gates on the Midway Plaisance leading up to the fair. In the end Cody exacted the perfect revenge for this slight: the Columbian Exposition went bankrupt, while his show took in more than $1 million.) Eugene was four and a half then, which explains his vivid memory of the Indians far better than if he were two or three. Thus O’Neill preceded Mark Twain, Helen Keller, Frederick Douglass, Jack London, Thomas Edison, and countless other illustrious visitors to the Chicago World’s Fair. Of course, they all witnessed the spectacle; O’Neill missed it by a day.

The Indians at O’Neill’s bedside, then, must have been Sioux warriors known as Ghost Dancers, a cohort of holdouts who called for war after the Wounded Knee Massacre left over 150 tribal members—men, women, and children—dead on December 29, 1890. Just three months after Wounded Knee, William Cody made a deal with Secretary of the Interior John W. Noble for the release of a hundred of these Ghost Dancers imprisoned at nearby Fort Sheridan in order to enlist authentic Indians for another European tour. “The Indians at Fort Sheridan are a nuisance,” the press reported, “and it is understood that Secretary Noble was only too glad of an opportunity to get rid of them. … The Indians were, of course, glad to do anything to get out of prison.”23 Among those captured were the Lakota Sioux medicine man Kicking Bear, a veteran of the battle of Little Big Horn, and another Lakota named Short Bull—both leaders of the Ghost Dance resistance. Each of them took Cody up on his offer, and each, it’s safe to say, would have left young Eugene with “the low-down on Custer.”

Nearly two dozen Sioux braves were coerced into playing “savages” for William Cody’s show, and the grotesquery involved was never lost on O’Neill. In a scene in his 1920 play Diff’rent, a spiteful ne’er-do-well mocks a woman for having “dolled” up with “enough paint on her mush for a Buffalo Bill Indian” (CP2, 36). Other than that, O’Neill only once addressed the plight of the American Indian in his plays. The Fountain (1922), his first historical drama and a failure at the box office, follows the adventures of the sixteenth-century explorer Juan Ponce de León, who joined Columbus on his second voyage to the New World. Juan is nearly killed in Florida by Seminoles. O’Neill depicts the Native tribesmen, like the novelist James Fenimore Cooper a century before him, as a proud and defiant but ultimately doomed people.

O’Neill related his memory of the Sioux visits over fifty years later in a New York penthouse amid frenzied preparations for the premiere of The Iceman Cometh, testifying to the impact of the experience on both his creative imagination and his politics. He passionately spoke out against the injustices visited upon Native tribes by the government, and he would shock an unsuspecting reporter at the time by delighting over the conclusion of Custer’s Last Stand: “The great battle in American history was the Battle of Little Big Horn. The Indians wiped out the whitemen, scalped them. That was a victory in American history. It should be featured in all our school books as the greatest victory in American history.”24

O’Neill’s friend the journalist Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant wrote about the tale’s evocation of the playwright’s cynicism that the American Dream was an insidious myth. “In so far as O’Neill has written of American life,” Sergeant’s unpublished notes on the subject read, “he has written its un-success story, discussed the places where the American dream has broken down into something rather raw and unacceptable.”25 Another interviewer took note of two paintings on the walls of his penthouse, one of a clipper ship and one of Broadway at theater hour. “There’s the whole story of the decline of America,” O’Neill told him. “From the most beautiful thing America has ever made, the clipper ship, to the most tawdry street in the world.”26

No single American more than William F. Cody trumpeted the virtues of Euro-American expansion across North America, and his legend only grew, long after his death in 1917, with the heightened mood of triumphalism that followed World War II. And no single writer could have done more to dispel the myth of those very same virtues than Eugene O’Neill, the wide-eyed child gazing up at those “big brown” figures looming over his sickbed in a Chicago hotel room.

School Days of an Apostate

Ella and James O’Neill settled on New London, Connecticut, as their permanent town of residence in 1885. Conveniently located halfway between the theatrical centers of New York and Boston, the whaling city turned summer resort was a sensible choice. Ella’s cousins on her mother’s side, the Sheridans and the Brennans, had lived in New London for some time, and James had theater friends who owned summer homes there as well. Second in importance only to New Bedford, Massachusetts, in the heyday of the whale oil trade, New London is situated at the mouth of the Thames River, a tidal estuary that connects points inland to Long Island Sound and the Atlantic Ocean. During the Revolutionary War, Benedict Arnold, then a British officer, personally orchestrated the town’s desolation by fire in one of the infamous traitor’s most vicious acts of betrayal against the revolutionary forces. But the townspeople rebuilt and soon after transformed the waterfront into a patchwork of multitiered clapboard, red brick, and granite shops and dwellings, bestowing on the port city one of the more picturesque skylines in New England.

New London’s economy foundered after the Civil War, by which time whale oil had been replaced by petroleum and natural gas; ever since, the citizenry of the “large small-town,” as O’Neill refers to it in Ah, Wilderness! (CP3, 5), has taken the fantasy of an imminent “renaissance” for granted. Real estate in New London was thus considered a strong bet in the late nineteenth century, and James O’Neill, with his Irishman’s faith in the surety of land to ward off poverty, was game to try his luck. After buying and inhabiting several rental properties, by the summer of 1900, when Eugene was eleven, the family occupied a Victorian-style residence at 325 Pequot Avenue. Horse-drawn carriages clopped back and forth along the west bank of the Thames from the majestic Pequot House resort hotel and the Pequot Summer Colony, the bailiwick of the town’s most elite families, to the downtown “Parade” a couple of miles north. For a few thousand dollars, James had Monte Cristo Cottage, as the house was soon called, renovated and enlarged using the abandoned structures of a schoolhouse and a general store. The O’Neills would spend their summers there, from June to September, for the next two decades. Monte Cristo Cottage was as close as the family would ever come to a true home.

When O’Neill was in his late thirties, he sketched out a diagrammatic account of his childhood development using what the founder of American psychiatry Adolf Meyer called a “life chart.”27 (Today a similar tool is referred to as a genogram.) O’Neill’s psychiatrist Dr. Gilbert V. Hamilton believed the exercise might help his patient at long last understand the painful and abiding resentments he’d clung to since childhood; in that way, perhaps, he might be released from over two decades of bondage to alcohol, which had by that time become untenable. O’Neill revealed in his chart that as a toddler, it was his English nurse Sarah Sandy, not his aloof mother Ella, who’d provided him with “mother love.” Sandy also brought him to novelty museums that displayed “mal-formed wax dummies” and enjoyed watching as the boy recoiled in horror. The nurse also, perversely, instilled in him an acute fear of darkness as a result of the ghoulish “murder stories” she delighted in telling before turning out his lights at bedtime, after which she coddled him with motherly love as he howled in fear. “Father would give child whiskey + water to soothe child’s nightmares caused by terror of dark,” O’Neill recalled in his chart. “This whiskey is connected with protection of mother—drink of hero father.”28

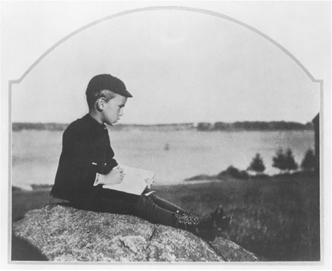

Eugene O’Neill in New London. Photo signed to “Carlotta Monterey O’Neill.”

(COURTESY OF THE YALE COLLECTION OF AMERICAN LITERATURE, BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY, NEW HAVEN)

![]()

Sarah Sandy was relieved of duty in the fall of 1895, not because of her unorthodox ideas of child rearing but rather because Eugene, not yet seven years old, was sent to St. Aloysius Academy in the Bronx, where he was instructed for four years by the Sisters of Charity. This point on O’Neill’s life chart reads, “Resentment + hatred of father as cause of school (break with mother). … Reality found + fled from in fear—life of fantasy + religion in school—inability to belong to reality.”29 O’Neill looked back on his exile as a cruel act of abandonment on the part of his parents, though his brother Jim had fared much better: he too was sent away before he turned seven, to Notre Dame’s preparatory school in South Bend, Indiana, but while there he blossomed socially and academically. It was a period of success for Jim that would constitute a painful reminder of his wasted intellectual potential once he reached adulthood.

Eugene O’Neill with James O’Neill Jr. and James O’Neill, left to right, in 1900 on the porch of Monte Cristo Cottage.

(COURTESY OF THE YALE COLLECTION OF AMERICAN LITERATURE, BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY, NEW HAVEN)

![]()

In 1900, O’Neill entered Manhattan’s De La Salle Institute on Central Park South and boarded with his family close by at a rented apartment on West Sixty-Eighth Street. One afternoon, arriving back from school early, he walked in on his mother holding a hypodermic needle. Indignant over the disruption, Ella accused him of spying; with little explanation, he was sent back to De La Salle the following fall as a boarder rather than a day student.30 A year later, O’Neill transferred to Betts Academy, a prep school in Stamford, Connecticut.

One summer night in 1903 after his freshman year of high school, the fourteen-year-old Eugene, his brother Jim, and his father all looked on, horror-stricken, as Ella made a desperate attempt on her life. Having run out of morphine, she ran headlong, wearing only a nightgown and shrieking like a madwoman, toward the Thames River across Pequot Avenue. The men rushed after her and stopped her before she could leap from the dock. James and Jim had been aware of Ella’s “problem” for years; but they had, right up to that moment, kept the truth from Eugene. “Jamie told me,” Edmund recounts bitterly of the incident in Long Day’s Journey Into Night. “I called him a liar! I tried to punch him in the nose. But I knew he wasn’t lying. (His voice trembling, his eyes begin to fill with tears.) God, it made everything in life seem rotten!” (CP3, 787).

O’Neill’s life chart makes it clear that this traumatic revelation triggered an instantaneous “discovery of mother’s inadequacy,” and here the “mother love” line on the chart drops off. The shock of Ella’s drug addiction, which in O’Neill’s mind was reserved for prostitutes and derelicts (though morphine use was endemic among well-heeled women at the time), along with the possibility that she might be insane, activated an addiction of the young man’s own: alcoholism,which began when he was fifteen and was eagerly reinforced by his ne’er-do-well brother Jim.31 (Only his parents and close family relations referred to him as “Jamie”; after O’Neill’s adolescence, he unvaryingly calls him “Jim.”) Jim also arranged for his younger brother’s loss of virginity to a prostitute in a two-bit Manhattan brothel. “Gene learned sin more easily than other people,” he boasted years after this event, which was severely traumatizing for his teenage brother. “I made it easy for him.”32 “The girls were such terrible creatures they forced whiskey down his throat,” O’Neill’s third wife, Carlotta Monterey, related of the incident decades later: “with Jamie helping them,” according to Monterey, “they tore off his clothes—he was fighting them. He wasn’t ready for that. He was reading a lot of poetry in those days. But later on he made himself at home in them, in the whorehouses.”33

Alcohol, often combined with sex, became a psychic painkiller for O’Neill, and over the years, drunkenness and even hangovers occupied his imagination as more reliable companions than the people who ostensibly loved him. For over two decades, O’Neill would drink himself into a stupor from morning to night, then dry out for weeks at a time in a state of utter loneliness and despair.

O’Neill also openly renounced his parents’ Catholicism after his mother’s breakdown—all religions, in fact—and became a confirmed atheist. “He rejected God,” O’Neill’s onetime girlfriend the Catholic Worker activist Dorothy Day wrote soon after his death. “He turned from Him.” That first Sunday morning after his mother’s attempt on her life, O’Neill refused to join his parents for Mass. A fight erupted between Eugene and James on the staircase in the front hall until the full-bodied James, who could have handily drubbed his son, abruptly stopped, straightened his cuffs, and said, “Very well. The subject is closed.”34 Though Ella would eventually conquer her morphine habit for good in 1917, thanks in part to the Sisters of Charity, her son never looked back.

O’Neill’s loss of faith was truly a loss—a profound emptiness, a breach in spirit. In Long Day’s Journey Into Night, O’Neill dramatizes a period when his mother had given up Mass as well. Her character, Mary Tyrone, longs to return to her convent schooldays when she embraced Catholicism. “If I could only find the faith I lost,” she laments, “so I could pray again!” (CP3, 779). In the final scene, locked in a morphine-induced dream state, Mary searches helplessly through the living room for something she’s misplaced, “something I need terribly. I remember when I had it I was never lonely nor afraid. I can’t have lost it forever, I would die if I thought that. Because then there would be no hope” (CP3, 826). O’Neill himself experienced this desperate search for hope and spirit. Had he been able to regain his Catholic faith, and his mother’s affection, or find a meaningful substitute, he would have felt safer and less alienated through life—but it’s more than likely he would never have achieved his stature as an artist.

The Greek philosopher Diogenes the Cynic made up his mind in the third century B.C. to cast off his worldly possessions and live the rest of his days in a bathtub. O’Neill viewed the tedium of life as a teenager at Monte Cristo Cottage in New London as even less exciting than this “Cynic Tub.” O’Neill would read in the morning, swim in the Thames in the afternoon, and read again at night, with little variation for weeks. Although his peripatetic childhood on the road instilled a powerful urge to find a “home” in the truest sense, it also intensified his view of Connecticut’s cultural life as impossibly parochial. At sixteen, he sneeringly claimed that each passing hour in New London was “equivalent to ten in any other place.” “Bored to death” with the dance “hops” at the Pequot House down the road, O’Neill would grumble that at least “in a graveyard there is some excitement in reading the inscriptions on the tombstones.”35

A welcome respite from this drowning ennui arrived in the summer of 1905 in the form of Marion Welch, a well-read teenager from the state capital of Hartford. Visiting a friend in New London that July, Welch was a couple of years older than Eugene, athletically built and, most important, intellectually curious. O’Neill would always think of their days together in his rowboat on the Thames as some of the happiest of his life. The surviving love letters to Marion read like those of a typical lovesick sixteen-year-old boy—thick with sarcasm and braggadocio, more Tom Sawyer than Baudelaire (that would come later). Written to impress more than woo, the letters boasted of joining his wayward brother Jim to bet on the “ponies,” play the slot machines, and carouse generally in upstate New York at Canfield’s Saratoga Club, “a refined name for one of the most fashionable (and notorious) gambling joints in the world.” He regarded Welch as his intellectual peer, and their letters over the course of their short-lived relationship reveal what books they were reading, which they planned to read next, and which weren’t worth reading at all. They shared what plays to see too: “So you went to see the old worm eaten Monte Cristo,” he responded to a letter from Marion. “It may be all right for those who have never seen it before.”36

Graduating from Betts Academy in the following spring of 1906, O’Neill next entered Princeton University, where he was determined to make up for lost time in New London and Stamford. His fellow students remembered him as a “loner,” though sarcastic and “foul-mouthed.” Most college boys in those days drank beer or wine; O’Neill, who was also a heavy smoker by this time, drank hard liquor, a choice his to-the-manner-born classmates associated with “bums.” O’Neill made them cringe with his blasphemy, and he regarded the school’s mandatory Sunday sermons as “so irritatingly stupid that they prevented me from sleeping.” On at least one occasion O’Neill, who by eighteen was nearly six feet tall, stood up on a chair and crowed at the ceiling with arms outstretched, “If there be a God, let Him strike me dead!” (Witnesses to this recalled that his ethnic pride surpassed his atheism, however, and “if anyone spoke disparagingly of Catholicism he would spring furiously to its defense.”)37

For the most part O’Neill kept a low profile during his first semester, when he was a resident of University Hall, now Holder Hall, and few Princetonians could claim they knew him well (though he was nicknamed “Ego” for his lack of humor concerning all things Eugene Gladstone O’Neill). His study was decorated with a fisherman’s net festooned with cork floats and sundry souvenirs, including, according to a fellow dormer, “actresses’ slippers, stockings, brassieres, playbills, posters, pictures of chorus girls in tights … and a hand of cards, a royal flush. But what got me was that among all this stuff he had hung up several condoms—they looked like they’d been used. Very gruesome.” The remainder of his suite contained a simple round table and chairs and a cramped bedroom with an iron cot, a washbowl, a water pitcher, and a commode. He retained his voracious reading habits, and he wrote some poetry, though not of the “highbrow” sort. One typical bit of doggerel composed during his short-lived period at the Ivy League school went something like this:

Cheeks that have known no rouge,

Lips that have known no booze,

What care I for thee?

Come with me on a souse,

A long and lasting carouse,

And I’ll adore thee.38

Pressed by classmates as to why he preferred the “stinking garbage pail” over a vase of fragrant roses, O’Neill replied enigmatically, “Both are nature,” a phrase that brings to mind one of O’Neill’s literary heroes, the French journalist and naturalist author Émile Zola. “When I go into the sewer, I go to clean it out,” the Norwegian “father of modern realism” Henrik Ibsen complained. “When Zola goes into the sewer, he takes a bath.” Zola countered such attacks by citing the physiologist Claude Bernard who, when asked about his “sentiments on the science of life,” responded that “it is a superb salon, flooded with light, which you can only reach by passing through a long and nauseating kitchen.”39

Broadly speaking, “realism” refers to the nineteenth-century revolt against melodrama and romanticism toward dramas that end with calculated ambiguity and reflect the contemporary lives of run-of-the-mill characters who, unlike in naturalism, exhibit free will. (It was this movement, led by Ibsen, that precipitated the end of the soliloquy.) “Naturalism” vaguely connotes a grittier, more perverse form of realism in common theater parlance. But once we remove realistic “slice-of-life” plays that share the “fourth-wall” illusion of most naturalistic dramas, naturalism distinguishes itself as a tradition of tragic endings, the exposure of sublime truths existing beneath surface realities, and the philosophical idea that individuals’ fates are determined by biological, historical, circumstantial, and psychological forces beyond their control. O’Neill’s future dramas would conflate naturalism with other techniques, but the naturalist tradition nearly always predominates.40

On the weekends, O’Neill divided his time between boozing at “Doc” Boyce’s nearby tavern and another local dive on Alexander Street with a noxious atmosphere that only he among his classmates could apparently stomach. But, as he had while at Betts, he also commuted to New York City every chance he got. He attended Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler that spring at the city’s Bijou Theatre on ten successive nights. Though as a playwright O’Neill would follow Zola’s naturalist path, Ibsen’s revolt against Victorian convention spoke to O’Neill more than any play he had yet seen: “That experience discovered an entire new world of the drama for me. It gave me my first conception of a modern theatre where truth might live.”41

Louis “Lou” Holladay, a New Yorker O’Neill had met during a sojourn to the city, arrived at Princeton’s campus one weekend armed with a handgun and a quart of absinthe, a potent liquor distilled from the toxins of the wormwood plant. O’Neill was enthralled by the hallucinogenic properties of the soon-to-be outlawed drink; he’d read about it in Wormwood: A Drama of Paris (1890) by the British novelist Marie Corelli and asked Holladay to bring a bottle down from the city. After consuming too much of the green-hued tincture in his room, O’Neill turned “berserk”—smashing furniture, hurling a chair through his window, and aiming Holladay’s revolver at its owner, then pulling the trigger. Luckily, the gun wasn’t loaded. It took three classmates to pin him down, tie him up, and heave him into bed.42 No lessons were learned, however, and his heavy drinking and unruly behavior only worsened that winter and spring.

O’Neill left the distinct impression among his classmates that he’d derived his cynicism from his “wild” and “worldly” older brother Jim. “There is not such a thing as a virgin after the age of fourteen,” O’Neill told them, sounding much like his brother; although when he dated a local girl from Trenton, the closest urban center to Princeton’s campus, he would “expiate in high dudgeon” if anyone uttered a disrespectful word about her. Once he took a couple of Princeton students to New York’s Tenderloin district, where the notorious Haymarket bar was located on the same block as an assortment of brothels in which he’d been initiated by Jim. (“Those babes gave me some of the best laughs I’ve ever had, and to the future profit of many a dramatic scene,” O’Neill said later.) His companions got cold feet and hastily retreated back to school.43

Late that spring semester, 1907, O’Neill went on a drunken spree through Trenton with a pack of like-minded students, and they missed the last trolley to Princeton. Instead, they caught the train to New York, which dropped them off at Princeton Junction; but the drawbridge was up, and they had to swim across Carnegie Lake. When a dog started barking on a railroad embankment leading down to a group of houses, O’Neill, drunk as a lord, began hurling stones at the animal. As the dog’s fury grew, so did O’Neill’s, and one of his stones went wide of its mark and crashed through a window of the house. Undeterred, he threw outdoor furniture next, thus rousing from bed the homeowner, a division superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The boys were suspended for three weeks.44

O’Neill’s academic standing had already been declining precipitously, and the incident proved a convenient excuse to end relations between O’Neill and the hallowed Ivy League school. (This would not be a permanent break, as decades later O’Neill would donate to its library a substantial cache of his manuscripts and letters.) “Princeton was all play and no work,” O’Neill said, “so much so that the Dean decided I had, by enormous application, crowded four years’ play into one, and he graduated me as a Master Player at the end of that year.” No love was lost between the two parties, nor was expulsion from college new to the O’Neill family: a decade earlier, Jim had been attending Fordham University, a Jesuit school, when he was expelled for hiring a prostitute, then introducing her to classmates and at least one priest on campus as his sister. At Princeton, O’Neill had been charged with “conduct unbecoming a student.” When asked later by a reporter why he was thrown out, he just chuckled and said, “General hell-raising.”45

Anarchist in the Tropics

James O’Neill landed his unrepentant son a position that summer making $25 a week in Manhattan as a secretary at the mail order house of the New York–Chicago Supply Company. O’Neill held the position for nearly a year but, he said, “never took it seriously.”46 His friend Lou Holladay’s sister Paula, known as Polly, ran a café on Macdougal Street in Greenwich Village that catered to the Village’s burgeoning avant-garde artistic and bohemian set. Without responsibility or purpose, O’Neill referred to this time as his “wise guy” period.47

Along with frequenting Polly’s, O’Neill and Holladay combed the bars and brothels of the Tenderloin district and soaked up the music of the era, O’Neill thus initiating his lifelong obsession with ragtime piano and early jazz. They also formed a close relationship with Benjamin R. Tucker, an iconoclastic publisher and editor of the anarchist journal Liberty. Tucker’s Unique Book Shop at 502 Sixth Avenue near Thirtieth Street was a preferred haunt for the growing cohort of what one reporter characterized as “well dressed, seemingly well-educated young men, whose mental processes have led them into out of the way or unconventional channels.”48 Tucker dedicated his life to promoting intellectual freedom and preached, in opposition to the “Communist anarchism” of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, nonviolent social and political protest. O’Neill thus adopted what became his only self-professed, lifelong worldview: “philosophical anarchism,” also known as “individualist anarchism” or “egoism.”

Philosophical anarchists maintained three chief principles: unconditional nonviolence, one-on-one instruction rather than mass propaganda, and the complete disregard of all social and political institutions (the press, organized religion, government, law enforcement, the military) as “phantasms,” “ghosts,” or “spooks” to exorcise from one’s mind. This last became a unifying theme in nearly all of O’Neill’s work. The anarchist Hartmann in O’Neill’s early play The Personal Equation (1915), for instance, refers to American notions of “fatherland or motherland” as a “sentimental phantom,” and he goes on to say that “the soul of man is an uninhabited house haunted by the ghosts of old ideals. And man in those ghosts still believes!” (CP1, 321). Over a decade later, O’Neill’s character Nina Leeds in Strange Interlude (1927) snarls at her upright friend Charlie Marsden about her desperate attempt to “believe in any God at any price—a heap of stones, a mud image, a drawing on a wall, a bird, a fish, a snake, a baboon—or even a good man preaching the simple platitudes of truth, those Gospel words we love the sound of but whose meaning we pass on to spooks to live by!” (CP2, 669). And by the 1930s, in his Faustian mask play Days Without End (1933), the protagonist’s masked doppelgänger scorns his alter ego’s longing for the “old ghostly comforts” of religion (CP3, 161).49

Tucker’s Unique Book Shop offered over five thousand volumes of what its proprietor advertised as “the most complete line of advanced literature to be found anywhere in the world,” and O’Neill later professed that his access to this eclectic library through this period had unalterably molded his “inner self.” Tucker translated a good deal of this outlaw literature for the first time into English and debuted American editions through his independent press; but he made a point to champion American philosophies as well: Thomas Jefferson’s suspicion of government power, Henry David Thoreau’s civil disobedience, and the intrepid poet Walt Whitman’s heightened individualism and lyrical call for radical democracy. The good gray poet responded in kind. “Tucker did brave things for Leaves of Grass when brave things were rare,” Whitman said. “I could not forget that. … I love him: he is plucky to the bone.”50

But the most vital source of Tucker’s philosophy could be found in the German philosopher Max Stirner’s radical manifesto The Ego and His Own: The Case of the Individual against Authority (1844), a volume listed on Edmund Tyrone’s bookshelf in Long Day’s Journey Into Night. Tucker had been obsessing over The Ego and His Own at the time O’Neill regularly frequented his shop in 1907, and his imprint published its first English translation that same year. Saxe Commins, the notorious anarchist Emma Goldman’s nephew and later a man O’Neill would identify as one of his “oldest and best of friends,” described Stirner’s book as “an anarchical explosion of aphoristic generalities, defiant and iconoclastic.”51 Stirner railed against “fixed ideas” the same way Ralph Waldo Emerson denounced “foolish consistency [as] the hobgoblin of little minds.” The Unique Book Shop stocked volumes by Proudhon, Mill, Thoreau, Tolstoy, Zola, Gorky, Kropotkin, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Shaw, but when O’Neill took his New London pal Ed Keefe to Tucker’s store, according to Keefe, O’Neill breezed past several packed shelves and “made” him buy The Ego and His Own.52

This steady drumbeat of the “self” that resounded through the cafés, barrooms, and alleyways of Manhattan emboldened O’Neill to quit his humdrum desk job at the shipping company. In the summer of 1908, scraping by on $7 a week from his father, he rented a studio in the Lincoln Arcade Building at Sixty-Fifth Street and Broadway with Ed Keefe, the painter George Bellows, and the illustrator Ed Ireland. Early in 1909, the bohemian cabal also lived for a month on a farm O’Neill’s father owned in Zion, New Jersey. As they cooked for themselves and tried to keep warm, Bellows and Keefe painted while O’Neill, according to him, “wrote a series of sonnets” that were little more than “bad imitations of Dante Gabriel Rossetti.”53

Bellows was a contributor to the radical organ the Masses and a student of the “Ash Can” painter Robert Henri (pronounced “Hen-Rye”).54 According to another of his students, Henri was considered a sort of mystic who lectured “with hypnotic effect.” He and other philosophical anarchists taught O’Neill and his cohort that by their example of “owning” their lives, Victorian moralists might follow suit and cease their meddling in the lives of others. The famed Ash Can School of painting was Henri’s invention, and he mentored a number of first-rate artists, including Bellows and a young Edward Hopper. O’Neill thus found himself among true believers in his naturalistic “stinking garbage pail” aesthetic—Henri taught his art students that painting must be “as real as mud, as the clods of horse-shit and snow, that froze on Broadway in the winter.” That year Bellows completed what would be his most famous painting, Stag at Sharkey’s, which featured an illegal boxing match at Tom Sharkey’s Athletic Club, a work of brutal realism meant to capture, Bellows explained simply, “two men trying to kill each other.”55

O’Neill reproduced this art-studio milieu in his first full-length play, Bread and Butter (1914), a tragedy about an artist in desperate revolt against bourgeois tastes. (In this way, Bread and Butter joins the tradition of George du Maurier’s Trilby [1894] and its American counterpart, Stephen Crane’s The Third Violet [1897].) The play’s master painter Eugene Grammont (based on Henri) declaims the philosophical anarchist’s credo to O’Neill’s loosely based alter ego, John Brown: “Be true to yourself … remember! For that no sacrifice is too great” (CP1, 148).

During that summer of 1909, O’Neill made the acquaintance of Kathleen Jenkins, the upright daughter of a respectable Protestant mother. (Her father, an alcoholic, had long ago abandoned them.) George Bellows encouraged the match, certain that O’Neill needed a “nice girl” like her for stability. At first Jenkins was attracted by the idea of a romance with a raffish intellectual like O’Neill, even if he had no job and few prospects for one. “The usual young man sent you flowers, a box of candy, took you to the theater, but mostly,” she said, since O’Neill never had any money, “we talked and walked. … He was always immaculately groomed, in spite of being unconventional; he led a bohemian sort of life. … The books he read were ‘way over my head.’”56 Jenkins was stable but not too “nice,” at least according to the standards of the day. She soon became pregnant, and as a result, they got married in a clandestine ceremony at Trinity Protestant Episcopal Church in Hoboken, New Jersey, on October 2, 1909.57

James and Ella were soon confronted at their suite at the Prince George Hotel on East Twenty-Eighth Street by Kathleen’s mother, Kate Jenkins, who told them about their children’s secret marriage and demanded to know what they planned to do about it. James was at first startled at Jenkins’s impudence, then infuriated. His solution for ending the relationship was to pack his son off on a mining expedition to Spanish Honduras with a gold-prospecting associate of his, Earl C. Stevens. James and Kathleen accompanied O’Neill to Grand Central Station to see him off on a train to San Francisco, and by his twenty-first birthday, October 16, O’Neill found himself contentedly drifting southward on a banana boat off the coast of Mexico.58

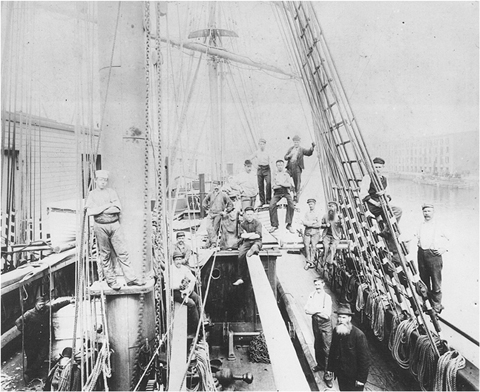

Eugene O’Neill with Earl C. Stevens on a banana boat en route to Honduras, October 16, 1909, O’Neill’s twenty-first birthday.

(COURTESY OF THE YALE COLLECTION OF AMERICAN LITERATURE, BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY, NEW HAVEN)

![]()

After traveling by mule from Amalpa for nearly a hundred unmapped miles through jungles and mountain passes, O’Neill and Stevens’s party finally arrived at the Honduran capital, Tegucigalpa. He had passed through stunning territory but was harassed, he reported back to his parents, by an endless horde of fleas and ticks “that burrow under your skin and form sores.” And in spite of his predilection for “the stinking garbage pail,” he found the squalor appalling: “Pigs, buzzard[s], dogs, chickens and children all live in the same room and the sanitary conditions of the huts are beyond belief.”59 The tropical climate, on the other hand, suited him just fine. It never went above eighty-five degrees during the day or below seventy at night. He enjoyed listening to the local bands in town squares while observing the “funny way everyone … struts around with a six-shooter and a belt full of cartridges on their hip—just like a 30 cent Western melodrama.” (O’Neill later penned his own cheap western melodramas, the one-act plays A Wife for a Life in 1913, the first play he ever wrote, and The Movie Man in 1914, and the latter’s 1916 short story version, “The Screenews of War.”) He also embraced the languorous pace of life in Central America: “If we don’t do it today why we can tomorrow—that is the way they seem to feel about it.” To fit in, O’Neill loaded himself down “like an arsenal with ammunition, knives, and firearms” and first cultivated what would become his iconic moustache, a disguise meant for circulating in the plazas, with the goal “to look absolutely as shiftless and dirty as the best of them.”60

O’Neill’s pumped-up spirit of adventure rapidly deflated, however, and after a couple of months he wrote his parents, “I give it as my candid opinion and fixed belief that God got his inspiration for Hell after creating Honduras.” At the same time, the ambiguous nature of his marital responsibilities still nagged at him. “It sure would be some shock to find out I was enduring all this for love,” he wrote them. “Better find out for me.” By Christmas in Guajiniquil, O’Neill was mired in self-pity. He hated the food—the meat rotten, everything fried and wrapped in tortillas, “a heavy soggy imitation of a pancake made of corn enough to poison the stomach of an ostrich”—and inevitably contracted food poisoning; the fleas, gnats, ticks, and mosquitoes had evolved from a mild nuisance to a dreadful plague; and his initial admiration for the Hondurans’ relaxed lifestyle had soured into a bilious contempt: “The natives are the lowest, laziest, most ignorant bunch of brainless bipeds that ever polluted a land and retarded its future. Until some just Fate grows weary of watching the gropings in the dark of these human maggots and exterminates them, until the Universe shakes these human lice from its sides, Honduras has no future, no hopes of being anything but what it is at present—a Siberia of the tropics.”61

A revolution broke out in Honduras while O’Neill was there, but he reassured his parents that its combatants were “of the comic opera variety and only affect Americans in that they delay the mail.” He begged them to send three pounds of Bull Durham tobacco and some magazines, then ended on a homesick note: “I never realized how much home and Father and Mother meant until I got so far away from them.” O’Neill was bedridden with malaria during his last three weeks in Tegucigalpa. He was given a bed at the American consulate, since the hotels were booked up, and his chills from fever became so relentless that his caretakers draped old American flags over him on top of whatever blankets they could spare. “I looked,” he said later, “just like George M. Cohan,” the American song-and-dance man best known for his performances of “Yankee Doodle Dandy” and “You’re a Grand Old Flag.” Many years later, O’Neill tersely summed up the ill-fated expedition: “Much hardship, little romance, no gold.”62

It had been a pleasant afternoon strolling along Fifth Avenue in that May 1910 when Ella O’Neill and a friend saw a nursemaid march by pushing a baby carriage carrying an adorable infant. Her friend instantly recognized the woman as an employee of O’Neill’s mother-in-law, Kate Jenkins. “Did you see that little boy?” she asked, waiting until they’d passed. “That’s your grandson!” O’Neill in fact returned from his exile in the “Siberia of the tropics” right on time for the embarrassingly public arrival of Eugene Jr., on May 5, 1910. Two days later, the New York World ran an article under the exuberant headline “The Birth of a Boy / Reveals Marriage of ‘Gene’ O’Neill / Young Man in Honduras, / Doesn’t Know He Is Dad / May Not Hear News for Weeks / Working at Mine to Win / Fortune for Family.” Another article on May 11 featured a photograph of Kathleen Jenkins with the accusatory caption, “Gene Home, / But Not with Wife.” Kate Jenkins was undoubtedly the source. “It seems impossible,” his mother-in-law was quoted as saying, “that ‘Gene’ is in town and has remained away from his wife and their baby. There must be some mistake, but if there is not, Eugene’s attitude is inexcusable. He knows how we all feel toward him and that he could have come to this house to live any time since his marriage to my daughter. There would have been no ‘mother-in-law’ about it, either, and he knew that. I felt toward him as if he were my own son.” Jenkins then insinuated, not without some basis of truth, that James O’Neill was responsible for keeping the young family apart.63

Kathleen Jenkins with Eugene O’Neill Jr.

(COURTESY OF SHEAFFER-O’NEILL COLLECTION, LINDA LEAR CENTER FOR SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES, CONNECTICUT COLLEGE, NEW LONDON)

![]()

With no game plan or prospects for employment in New York, O’Neill joined his father on a boondoggle to St. Louis, Missouri, for James’s traveling production of The White Sister, another of his numerous though commonly forgotten departures from Monte Cristo over the years. O’Neill slogged along as an assistant manager and security man at the ticket counters; but when they arrived in Boston, he once again fled the country—this time as a passenger on the Norwegian bark Charles Racine, skippered by the highly competent Captain Gustav Waage and bound south for Buenos Aires. The voyage cost James O’Neill $75, no paltry sum given that the ship’s crew earned between $13 and $14 a month.64 Once under way, the Charles Racine sailed for weeks with no land in sight,65 during which time O’Neill composed the poem “Free,” his earliest known literary work. (Several years after publishing it in the Pleiades Club Year Book in 1912, he admitted to the club, a hail-fellow-well-met group of bohemian patrons and dilettante practitioners of the arts, that the poem was “actually written on a deep-sea barque in the days of Real Romance.”)66 In the poem, O’Neill acknowledges the deep remorse he felt over his desertion of Kathleen and Eugene Jr. while at the same time revealing a profound spiritual release:

I have had my dance with Folly, nor do I shirk the blame;

I have sipped the so-called Wine of Life and paid the price of shame;

But I know that I shall find surcease, the rest of my spirit craves,

Where the rainbows play in the flying spray,

’Mid the keen salt kiss of the waves.67

Time spent with the crew aboard the Charles Racine—“At last to be free, on the open sea, with the trade wind / in our hair”—would instill a lifelong infatuation with a spiritual transcendence he would never achieve again; and the impact of this seminal voyage would find its most lyrical expression in Edmund Tyrone’s monologue from Long Day’s Journey Into Night:

When I was on the Squarehead square rigger, bound for Buenos Aires. Full moon in the Trades. The old hooker driving fourteen knots. I lay on the bowsprit, facing astern, with the water foaming into spume under me, the masts with every sail white in the moonlight, towering high above me. I became drunk with the beauty and singing rhythm of it, and for a moment I lost myself—actually lost my life. I was set free! I dissolved in the sea, became white sails and flying spray, became beauty and rhythm, became moonlight and the ship and the high dim-starred sky! I belonged, without past or future, within peace and unity and a wild joy, within something greater than my own life, or the life of Man, to Life itself! To God, if you want to put it that way. (CP3, 811–12; emphasis added)

The Charles Racine carried over a million feet of lumber below decks, and the overload was lashed to the upper decks and hatches with chains and wiring. The trip lasted sixty-five days, an exceptionally long haul for the heavily trafficked lumber route from Boston to Buenos Aires; if it exasperated the crew, for O’Neill the prolonged trip was a boon. Not only did he take in the stories of the men about their ports of call and commit traditional sea shanties to memory, the voyage also offered him a glimpse of the full range of extreme conditions at sea, without the stabilizing force of engine power, from the stillness of a ship becalmed to terrifying hurricane conditions.68

O’Neill greatly admired the sailors he met onboard, and he later broadened his respect for their straight-talking swagger to include the working classes as a whole: “They are more direct. In action and utterance. Thus more dramatic. Their lives and sufferings and personalities lend themselves more readily to dramatization. They have not been steeped in the evasions and superficialities which come with social life and intercourse. Their real selves are exposed. They are crude but honest. They are not handicapped by inhibitions.”69 “O’Neill was well-liked onboard,” said one of the crew of the Charles Racine. “We thought him an interesting strange bird we all loved to talk to.” “It’s strange,” O’Neill wistfully recalled decades later, as death approached, “but the time I spent at sea on a sailing ship was the only time I ever felt I had roots in any place.”70

On the afternoon of July 24, 1910, a fierce hurricane pummeled the ship. Captain Waage, alarmed by his barometer’s plummeting descent, noted in his log a “terrific heavy sea. … Some deck cargo—planks—washed over.” From the relative safety of the forecastle alleyway, O’Neill looked on in awe while the crew members relieved one another to stand watch in the crow’s nest. They would pause until a wall of water crashed down on deck, and then, when it had receded into the billowing swells, they sprinted across the slippery deck to the mainmast, while the previous man on watch would climb down and perform the same treacherous maneuver in reverse. The brutal winds had died down by morning only to rematerialize as “violent hurricane squalls” outside Buenos Aires at the mouth of the Rio de la Plata, the massive estuary separating Uruguay and Argentina. After this, the deck boy, Osmund Christophersen, asked O’Neill what he thought of the rough weather. “Very interesting,” he replied, “but I could have wished for less of it.”71

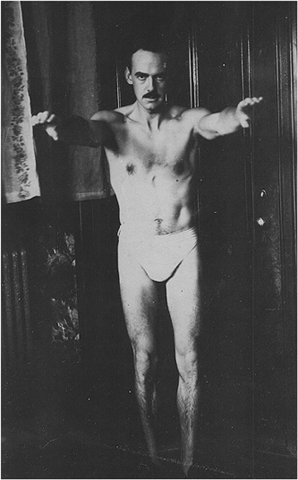

Crew of the S.S. Charles Racine.

(COURTESY OF SHEAFFER-O’NEILL COLLECTION, LINDA LEAR CENTER FOR SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES, CONNECTICUT COLLEGE, NEW LONDON)

![]()

Once the Charles Racine had docked safely at Buenos Aires in early August, agents scrambled onboard from local bars and brothels to pass around advertisement cards designed to entice sailors eager to blow off steam after weeks of toil at sea: “Come up to my house, plenty fun, perty girls, plenty dance, three men killed last night.” In due course, after O’Neill checked in at the deluxe Continental Hotel, he trailed the swarm of thirsty seamen down Avenida Roque Sáenz Peña toward Paseo de Julio. It wasn’t long before O’Neill ran short of cash and had to swap the downy beds of the genteel Continental for the debauched thoroughfare’s rigid public benches. The Argentine author Manuel Gálvez depicted the Paseo de Julio much as O’Neill must have first seen it for himself: “His artist’s soul forgot for an instant the penury of his life. Because he found this street fantastic, with its high arcades; its cheap, foul shops; its kaleidoscopes with views of wars and exhibitions of monsters; the dark hotels that rented out dirty beds for occasional lovers; the sinister cellars that stunk of grime and where sailors reeking of booze sang; its whores, who were the dirtiest dregs of society; its vagabonds who slept under the columns of the arches; its sellers of obscene pictures; the nauseating stink of human dirt.”72

For nine squalid months O’Neill worked odd jobs and lived hand-to-mouth, touring the city’s brothels and attending the pornographic “moving pictures” playing in the suburb of Barracas. He ate little and drank all day; if he had enough money, his drink of choice was a jar of gin with a dash of vermouth and soda. If he didn’t, he drank the local beer. “I wanted to be a he-man,” O’Neill said. “To knock ’em cold and eat ’em alive.” Much of his time was spent at a waterfront saloon called the Sailor’s Opera. “It sure was a madhouse,” he recalled. “Pickled sailors, sure-thing race-track touts, soused boiled white shirt déclassé Englishmen, underlings in the Diplomatic Service, boys darting around tables leaving pink and yellow cards directing one to red-plush paradises, and entangled in the racket was the melody of some ancient turkey-trot banged out by a sober pianist.”73

After a month or so “on the beach” (sailor talk for being stuck in port), O’Neill reluctantly looked for more steady employment. He worked for a time as a longshoreman on another square-rigger, the Timandra, whose “old bucko of a first mate was too tough,” he said, “the kind that would drop a marlin spike on your skull from a yardarm.” (The ship appears as the Amindra in The Long Voyage Home, O’Neill’s 1917 one-act about a shanghaied sailor.) He worked brief stints at several other jobs, including at the Westinghouse Electrical Company, “the wool house of a packing plant” at La Plata, and as a repairman for the Singer Sewing Machine Company. La Plata was the worst of them; the worst job, in fact, he would ever have. O’Neill was assigned the odious task of sorting raw hides, while the noxious fumes of the carcasses permeated his hair, clothing, nose, eyes, and mouth. He was about to relinquish his post when a warehouse fire saved him the trouble, and the fetid compound burned to the ground. (“I didn’t do it,” he said, “but it was a good idea.”)74 Working for Singer Sewing Machine was only slightly less demoralizing. “Do you know how many different models Singer makes?” the boss asked him at the job interview. “Fifty?” “Fifty! Five hundred and fifty! You’ll have to learn to take each one apart and put it together again.” O’Neill couldn’t bear the mechanical drudgery for long, and he quit. “And then I hadn’t any job at all,” he recollected, “and was down on the beach—‘down,’ if not precisely ‘out.’”75

One day a man of O’Neill’s tastes, a socialist and freelance reporter for the Buenos Aires Herald named Charles Ashleigh, walked into a seaman’s café, probably the Sailor’s Opera, and, seeing there wasn’t a vacant table, “picked one where but a single customer was sitting—a rather morose, dark young American.” Ashleigh ordered a schooner of beer and sat quietly listening to a mulatto piano player “pounding out popular tunes.” But after ordering a second schooner, he threw caution to the wind and blurted out, “Good Lord, I’m sick of this. I haven’t talked with a soul all day.” “Nor have I,” replied O’Neill. “Have another drink?” That night they stayed up for hours “talking, talking, talking,” said Ashleigh, about “sailing ships and steamships, Conrad and Yeats, the mountains and ports of South America, politics and the theater.” They also exchanged drafts of each other’s verse “across the sloppy table, read, discussed, criticized.”76

For decades scholars believed that none of O’Neill’s writing from Argentina had survived. But in the spring of 1917 at a saloon in Greenwich Village, O’Neill showed Robert Carlton Brown, a fiction writer and editor at the Masses, a poem he said he’d written in Buenos Aires entitled “Ashes of Orchids.”77 Unpublished before now, here is the earliest version of this poem, which O’Neill later revised in the summer of 1917 with the new title “The Bridegroom Weeps!”:

In my eyes

Burning, unshed:

There are so many ashes

In my mouth

Ashes of orchids:

There are so many corpses

In my brain

Of decomposing dreams—

And Columbine, also,

Decomposes!78

“The Bridegroom Weeps!” is O’Neill’s second known literary effort after “Free.” No doubt the poem, like “Free,” was partially inspired by Kathleen Jenkins, but his guilt over her and Eugene Jr. was now combined with his hopelessly dissolute life in Argentina. O’Neill often recycled his own phrasing from the past, and the title would later inform those of his biblical mask play Lazarus Laughed (1926) and, more important, his late masterwork The Iceman Cometh (1939).

A more substantial literary legacy from Buenos Aires materialized in the figure of a young Englishman at the Sailor’s Opera, a man the future playwright later mirrored in Smitty, the antihero of his 1917 one-acts The Moon of the Caribbees and In the Zone. O’Neill regularly observed his future inspiration “sopping up all the liquor in sight, and between drunks he’d drink to sober up. He almost caused an alcoholic drought in Buenos Ayres.”79 In his midtwenties, blond, and “extraordinarily handsome,” Smitty was, O’Neill said, “almost too beautiful … very like Oscar Wilde’s description of Dorian Gray. Even his name was flowery.” O’Neill describes him in The Moon as “a young Englishman with a blonde mustache” who speaks to other sailors “pompously” and exudes an attitude of unearned entitlement (CP1, 528, 538); the actual Smitty was similarly an aristocratic, college-educated, former member of a “crack British regiment,” according to O’Neill, who “suddenly messed up his life—pretty conspicuously.”80

Smitty had escaped to Buenos Aires to evade a scandal at home, and though armed with letters from British dignitaries to Argentine counterparts, he was deathly afraid that someone might offer him a job, so he kept the letters to himself.81 One drama critic quipped that O’Neill’s fictional character was “an uninteresting young man,” but this was precisely O’Neill’s point.82 The true hero of The Moon of the Caribbees, chronologically the first of his S.S. Glencairn series of one-act sea plays, was not Smitty, O’Neill clarified, but rather “the spirit of the sea—a big thing.” Smitty went to sea to forget his past, and he drinks to forget it too. But everything the sea offers in the play—the drink, the music, the local women, the moonlight—combines to become a potent reminder of a life half lived. Oblivious to the beauty of the sea and the other sailors’ unselfconscious revelry, Smitty’s “silhouetted gestures of self-pity are reduced to their proper insignificance.” For O’Neill, he’s a hollow “insect” ineffectually buzzing amid the wonder of nature’s “eternal sadness.” Smitty lives his life “much more out of harmony with truth, much less in tune with beauty, than the honest vulgarity of his mates.”83 With the notable exception of Smitty, O’Neill’s maritime plays express nothing but admiration for the seamen he encountered. “I hated a life ruled by the conventions and traditions of society,” O’Neill said. “Discipline on a sailing vessel was not a thing that was imposed on the crew by superior authority. It was essentially voluntary. The motive behind it was loyalty to the ship!”84

In due course, O’Neill became fed up with the vagabond lifestyle of a penniless beachcomber, “sleeping on park benches, hanging around waterfront dives, and absolutely alone.” At one point, he was tempted to partner up with an out-of-work railroad man to hold up a currency exchange at gunpoint. O’Neill considered the proposal seriously but turned the hopeless robber down. “He was sent to prison,” he said, “and, for all I know, he died there.” The capture of his would-be accomplice served the future playwright as a keen reminder of life’s fragility in the hands of pitiless circumstance: “There are times now when I feel sure I would have been [a writer], no matter what happened, but when I remember Buenos Aires, and the fellow down there who wanted me to be a bandit, I’m not so sure.”85

O’Neill shipped out of Buenos Aires aboard the tramp steamer S.S. Ikala in March 1911, but this time as a seaman, not a passenger. After a brief stopover at Port of Spain, Trinidad (the harbor of which inspired the mise-en-scène for The Moon of the Caribbees), the Ikala docked in New York on April 15. As his poems “Free” and “The Bridegroom Weeps!” indicate, O’Neill’s guilty feelings still lingered over Kathleen Jenkins and Eugene Jr., and by telephone he arranged with Jenkins to stop by and visit his one-year-old namesake. The reunion between husband and wife was civil but awkward; of the few words spoken by O’Neill, none of them justified his behavior over the last year and a half. After a brief stay, he left in silence. O’Neill wouldn’t see Eugene Jr. for more than a decade, and Jenkins he never saw again.86