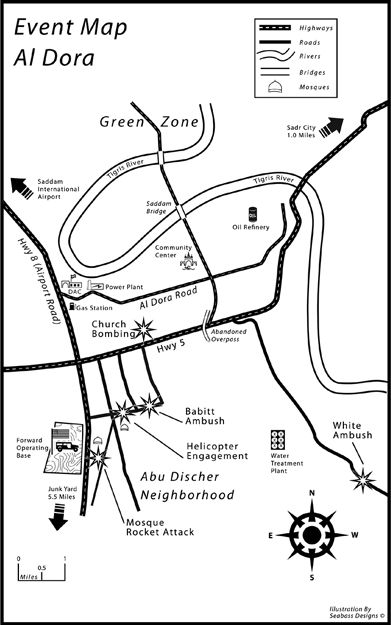

THIS BOOK IS THE STORY of an army officer’s winding road down into a moral morass, where bribes and blood money, not principle, governed the dissemination of power and the possibility of survival. In March 2004, as a captain in the U.S. Army, I was appointed the governance officer for Al Dora, one of Baghdad’s most violent districts. My job was to establish and oversee a council structure that would allow Iraqis to begin governing themselves and reconstruct their homeland. I had received no training whatsoever for the post—in fact, the role of a governance officer wasn’t even part of an armor battalion’s organization—but I believed in myself and in what we were trying to achieve in Iraq. I wanted to do something good, something significant. I wanted to help. Yet in a place of extreme violence and devoid of order, the practical subsumes the principle, and I drifted down the path of bribery and corruption that seemed endemic on the streets of Baghdad. Instead of a principled council structure, I watched the evolution of a tangled web of alliances based on power, opportunity, and survival.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, a fellow West Point graduate, summed up his feelings of war more succinctly than many before or since when he said, “I hate war as only a soldier who has lived it can, only as one who has seen its brutality, its futility, its stupidity.” That is a sentiment not well understood by those outside the military, especially by those indifferent masses who, between meals at the drive-thru, find a spare minute to tie a yellow ribbon on a tree and congratulate themselves for being patriotic. In short, it is not well understood by those who have no idea how to sacrifice or what it means to fight a war that they know isn’t right.

This is not a traditional war story. This is not about a black-and-white world, with intrepid American heroes versus murderous villains. Nor is this a story about greedy defense contractors throwing lavish parties with imported alcohol or the hedonism of young State Department workers reveling in the Green Zone. Those stories have been written, and they have been well received. Instead, this is the story of forging alliances and friendships, with money and violence, among the Iraqi people in the alleys of a Baghdad district amid the chaos of war. It is the story of paying people to attend coalition events and council meetings to preserve the pretext that democracy was taking root—long enough for us to receive promotions and please the politicians. It is a story about moral relativism and changing value systems to accommodate the daily demands of desperate circumstances.