Masthead of the Balance & Columbian Repository, Hudson, New York, which printed the first definition of the word “cocktail” in 1806. Courtesy of Ted Haigh.

UPSTATE NEW YORK AND

THE ORIGINS OF THE COCKTAIL

HISTORY, STORIES, LEGENDS

On May 13, 1806, the editor of a newspaper serving Hudson, New York, responded to a query from a reader. The reader had encountered the phrase “cock tail” in the previous week’s edition and wondered what it meant.

“Cock tail, then,” the editor wrote, “is a stimulating liquor, composed of spirits of any kind, sugar, water and bitters.”

That answer established an enduring link between Upstate New York and that great American invention, the cocktail.

It may not have been the first known use of “cock tail” or “cocktail” in print, though it certainly seems to be an early one. It does appear to be the first time in recorded history that the word was accompanied by a definition of a certain type of mixed alcoholic drink.

In 1806, Hudson was a prosperous whaling and merchant town on the Hudson River south of Albany. There seems to be no specific reason why it should be a cradle of the cocktail. But Hudson isn’t the only Upstate locale with a claim to cocktail history.

Folks in Lewiston, on the Niagara River near Niagara Falls in western New York, contend that their town is the place where, for the first time, a tavern keeper placed a rooster’s feather in a drink and called it a “cock tail.”

A place called the Four Corners in Westchester County (near the current town of Elmsford) has a related claim. In his Revolutionary War novel The Spy, author James Fenimore Cooper assigns the birth of the feathery drink called the cocktail to a woman running a tavern in Four Corners. That may have been the first recorded use of the word cocktail in fiction. It turns out that Cooper, a native Upstate New Yorker, once spent some time in Lewiston, where he may have first heard (or even witnessed) the cocktail story.

Masthead of the Balance & Columbian Repository, Hudson, New York, which printed the first definition of the word “cocktail” in 1806. Courtesy of Ted Haigh.

James Fenimore Cooper, author of The Spy. New York Public Library.

The actual origin of the cocktail—the word and the drink—is steeped in mystery, speculation and outright fantasy. “The word ‘cocktail’ itself remains one of the most elusive in the language,” William Grimes wrote in his 2001 book, Straight Up or On the Rocks: The Story of the American Cocktail.

In 1946, the writer H.L. Mencken, who had made up a number of specious cocktail stories of his own, compiled a book called American English. Among the many words and phrases he tried to track down was “cocktail.” He found at least forty different origin stories, or etymologies. “Nearly all of them,” he wrote, “are no more than baloney.”

In recent years, no one has done more to track down the origins of the cocktail and sort out the baloney than author and drinks historian David Wondrich. His works include Imbibe!, a history that traces the cocktail primarily through the life and work of celebrated nineteenth-century mixologist Jerry Thomas (who, it should be noted, was born in the Upstate New York town of Sackets Harbor on the shore of Lake Ontario).

“Every single one of the drink’s early mentions fits neatly into the triangle between New York (City), Albany, and Boston,” Wondrich wrote in an appendix to Imbibe!, published in 2007. “If we follow the available evidence, then the Cocktail originated somewhere in the Hudson Valley, Connecticut or western Massachusetts.”

In a 2016 article for Saveur magazine, titled “Ancient Mystery Revealed! The Real History (Maybe) of How the Cocktail Got Its Name,” Wondrich re-examined that conclusion. He admits to “poking around” Lewiston for answers. He also traces the links between that story and Cooper’s fictional account in Westchester County.

“The history of the cocktail—and here I mean the original cocktail, the ur-mixture of spirits, bitters, sugar, and water that spawned the whole enticing tribe—has (perhaps not surprisingly) always been like this: heady with false leads and spiked with treacherous maybes,” Wondrich concludes.

Yet that Upstate New York connection persists. The river town of Hudson. Lewiston on the Niagara. Westchester County. Plot those places on a map and you get a triangle that neatly fits the place we call Upstate.

Maybe—just maybe—the cocktail was born in Upstate New York.

WHAT IS A COCKTAIL, ANYWAY?

Today, the cocktail encompasses a whole array of mixed alcoholic beverages. Back in the early 1800s, there were already other several identifiable types of mixed drinks. Punch was a popular type, as were the sangaree, the julep, the nog, the toddy, the cobbler, the shrub and others.

So was a concoction called a sling. The Hudson newspaper account, after dispensing the aforementioned definition of cocktail, says it is “vulgarly called a bittered sling.” The sling—spirits, sugar and water without the bitters—was already a known item. In any case, once the name “cocktail” took hold, it veered away from the original definition. Notably, while some latter-day cocktails still contain bitters, many do not.

“Americans still drink all sorts of things before, during and after a meal and would probably call every one of them a cocktail if it was cold and had some spirit as a base,” Grimes writes in Straight Up or On the Rocks. “‘Cocktail and ‘mixed drink’ have often become synonymous,” he notes, although the cocktail has even grown to include single-ingredient drinks.

“Common sense and custom suggest that a cocktail should be cold and snappy,” he continues. “It should be invigorating to the palate and pleasing to the eye. That covers most of the territory.” That’s how martinis and Manhattans, margaritas and mai tais, not to mention all sorts of highballs, shots and more come to be known today as cocktails.

But did cocktails get their start in Upstate New York?

THE CASE FOR HUDSON

In the 2016 article for Saveur, Wondrich describes the early newspaper reference in Hudson as “well worn.” By that he means it’s appeared in almost every cocktail book written in the past century. The key passages show up in two consecutive issues of the newspaper, which went by the name Balance & Columbian Repository, on May 6 and May 13, 1806.

The newspaper, like many in those days, was partisan in its politics. The Balance was firmly in the camp of the Federalist Party (George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and so on) and was in favor of a strong national government. It opposed the Democrats (Thomas Jefferson, among others) who stood for decentralized government. In 1806, Jefferson was president. The Balance introduced the word “cock-tail” on May 6, when it took a swipe at a Democratic candidate for state legislature in nearby Claverack, New York. That Democrat apparently had “used up the town’s stocks of alcohol in a frenzy of boozy vote-buying.” The article went on to list the candidate’s tab as covering “720 rum-grogs, 17 dozen brandies, 32 gin-slings, 411 glasses of bitters and 25 dozen ‘cock-tails.’”

The next week, the historic cocktail definition appears in what is essentially the letters to the editor section. The reader’s query, written in that wonderfully archaic early American style, was in response to the article on the candidate in Claverack:

Sir, I observe in your paper of the 6th inst. in the account of a democratic candidate for a seat in the Legislature, marked under the head of Loss, 25 do., “cock tail.” Will you be so obliging as to inform me what is meant by this species of refreshment?…I have heard of a “jorum” of “phlegm cutter” and “fog driver,” of “wetting the whistle” and “moistening the clay,” of a “fillip,” a “spur in the head,” “quenching a spark in the throat,” of “flip,” etc., but never in my life, though I have lived a good many years, did I hear of a cock tail before. Is it peculiar to this part of the country? Or is it a late invention? Is the name expressive of the effect which the drink has on a particular part of the body? Or does it signify that the Democrats who make the potion are turned topsy-turvy, and have their heads where their tails are?

The editor, Harry Croswell, responded:

As I make it a point, never to publish any thing (under my editorial head) but what I can explain, I shall not hesitate to gratify the curiousity of my inquisitive correspondent—Cock tail, then, is a stimulating liquor, composed of spirits of any kind, sugar, water, and bitters—it is vulgarly called a bittered sling and supposed to be an excellent electioneering potion, inasmuch as it renders the heart stout and bold, at the same time that it fuddles the head. It is said also, to be of great use to a Democratic candidate: because, a person having swallowed a glass of it, is ready to swallow anything else. {Edit. Bal.}

So much for not mixing drinks and politics.

In any case, “these two issues of the Balance & Columbian Repository of Hudson, New York, are two of the three primary signposts of the cocktail’s holy grail…its origin,” cocktail historian, author and collector Ted Haigh wrote in a 2009 article for Imbibe magazine. The third signpost Haigh cites is an 1803 use of the word in a newspaper called the Farmer’s Cabinet, published in New Hampshire. That reference, although earlier than the one in the Balance, did not define it.

In his 2009 book, Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails, Haigh writes that in the Farmer’s Cabinet the cocktail “was cited with barely contained contempt… as evidence of the intemperance of modern urban youth.” The Balance reference, he notes, was “not particularly positive” either.

Cocktail historians, nevertheless, agree that the drink as defined in the Balance is significant, even if it came amid partisan political wrangling. “This [politics], not cocktails, provided the interest Americans followed with wonder,” Haigh wrote in Imbibe. “Yet, it was in this setting that the cocktail was defined and introduced into the larger world.”

In Straight Up or On the Rocks, Grimes introduces the Hudson Balance definition by noting that “[t]he mixing of whiskey, bitters, and sugar represents a turning point, as decisive for American drinking habits as the discovery of three-point perspective was for Renaissance painting. It is the beginning of the cocktail in modern form.”

THE “HUDSON” COCKTAIL TODAY

What would a version of the drink that Harry Croswell defined in the Balance look and taste like today?

One obvious comparison is to the drink now called the Old Fashioned, though at certain times in recent history the link would have been unrecognizable.

In Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails, Haigh says the Old Fashioned stems from a drink called the Whiskey Cocktail, which in early renditions contained Croswell’s ingredients: spirits (in this case, rye whiskey), plus water, sugar and bitters. It also contained an orange liqueur called curaçao. Later versions abandoned curaçao, substituting orange peel. “As the years wore on, it morphed into a veritable fruit cocktail with oranges, orange juice, cherries, and sometimes a piece of pineapple—oft times all mushed together or shaken together with blended whiskey.”

Haigh, at the back of his book, rebuffs that muddle and offers a leaner version of the Old Fashioned that seems more in keeping with the Hudson original:

The Old Fashioned

Adapted from Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails by Ted Haigh

2 dashes bitters

½ teaspoon sugar

A few drops of water

2 ounces (or so) of rye or bourbon whiskey

A broad swathe of orange peel

Muddle the bitters, sugar and water in an Old Fashioned glass. Add a lump or two of ice, then the whiskey. Stir and serve with the orange peel. (The peel may be lightly muddled to express the oil.)

Another modern drinks author, Eric Felten, took a stab at an up-to-date version of the drink defined by Croswell in the Balance in his 2007 book, How’s Your Drink? Cocktail, Culture and the Art of Drinking Well.

Felten’s recipe follows a lively account of Croswell’s antagonism to President Jefferson and a description of a case in which Jefferson sued Croswell for libel. (Jefferson ultimately lost.) Felten, drinks columnist for the Wall Street Journal, uses gin as the base for his Hudson Balance-inspired cocktail.

Bittered Gin Sling

From How’s Your Drink? by Eric Felten

1½ ounces gin

¾ ounce sweet vermouth or sherry

½ ounce lemon juice

½ ounce simple (sugar) syrup

A dash or two of Angostura bitters

Soda water

Lemon peel

Shake all but the soda water with ice. Strain into a tumbler or highball glass over ice and top with soda. Garnish with lemon peel.

Reinventing Hudson’s “Original” Cocktail

Of course, to find a modern interpretation of the original Hudson cocktail, it makes sense to visit Hudson itself.

Today, Hudson is still a vibrant river community, the kind of place where busy and relatively affluent folks from New York City and other metropolitan areas like to build weekend or summer getaways. That means it’s filled with first-class bars and restaurants, aimed at a twenty-first-century audience that has grown up with the farm-to-table (locally sourced) food movement and the cocktail resurgence.

Jori Jayne Emde and her husband, James Beard award-winning chef Zack Pelaccio, are among the food and beverage stars to arrive in the Hudson area recently. They operate Fish & Game, a rustic yet classy place featuring set, full-course seasonal dinner and brunch menus. The search for a modern interpreter of the Hudson cocktail leads to Emde, who manages the bar program at Fish & Game.

Jori Jayne Emde, of Fish & Game restaurant in Hudson, created these cocktails inspired by the first definition of the cocktail in a Hudson newspaper. Author’s photo.

She and Pelaccio met when she went to work as a sous chef at his Fatty ’Cue restaurant in New York City. They came Upstate after Pelaccio bought property in the rural community of Old Chatham in 2005. “There is no town in Old Chatham, so when we wanted to go out, we came to Hudson,” Emde said. “We could easily see the potential with the historic buildings and just the vibe that was going on. We dug it.” They opened Fish & Game in 2014 and later became partners in another spot, Back Bar, just a block or so away.

Emde, who grew up in Austin, Texas, is fascinated by Hudson’s history, including its status as a wealthy whaling town in colonial days. (American whalers, it seems, brought their catch upriver to processors in Hudson to avoid contact with British authorities and their taxes.) Even as the town later fell on hard times, Emde says, the history is interesting. “I liked the seediness of it, all the brothels and bars and the dirty politicians as the wealth declined.”

She has heard the story of the Hudson Balance and its place in cocktail history. Like others, she is not completely convinced that the cocktail was invented here. “It was certainly the first place where it was documented, and that’s cool,” she says. For this book, Emde prepared two cocktails that meet the definition of editor Harry Croswell’s original cocktail.

The first is a version of a mint julep. Emde said she chose it partly because the julep was already a popular drink in 1806. Also, she notes that “the original juleps had bitters in them.” Emde makes her own bitters at the farm in Old Chatham, under the name Lady Jayne’s Alchemy. Here’s her version of a julep, in the “original Hudson cocktail” style.

Hudson Mint Julep

From Jori Jayne Emde of Fish & Game, Hudson

5 to 6 mint leaves, torn

2 ounces bourbon

¼ ounce mint syrup

1 bar spoon of ginger bitters (Lady Jayne’s Alchemy)

In a julep cup, muddle the mint leaves lightly to express the oils. Add the bourbon, mint syrup and ginger bitters. Fill half the julep cup with ice and then stir with a spoon until the cup develops a frost on the outside. Top off with more ice. Take a sprig of mint and slap it between the palms of your hands to express the oils and place in the drink for a beautiful garnish and refreshing nosegay while you sip.

The “Hudson” Mint Julep, created by Jori Jayne Emde of Fish & Game in Hudson. Its ingredients include bitters made by Emde’s company, Lady Jayne’s Alchemy. Author’s photo.

Emde’s second drink has a rum base. Rum was by far the most popular spirit in early American history. It was widely manufactured in New England—and even just north of Hudson in Albany—from Caribbean sugar and molasses. (We’ll have more to say on rum in Upstate New York in the next chapter.)

Bittered Sling with Rum

From Jori Jayne Emde of Fish & Game, Hudson

1½ ounces white rhum agricole

1 ounce dark rum

½ ounce fennel bitters (Lady Jayne’s Alchemy)

A few dashes of orange bitters

¼ ounce oleo saccharum (see note below)

Add all ingredients to an ice-filled shaker. Shake and strain into an ice-filled highball glass. Garnish with a piece of lime or orange peel and a brandy-soaked cherry.

Note: Oleo saccharum is made by mixing sugar and citrus peels, muddling them to express the oils and then letting it sit for about two weeks in a closed container at room temperature. “The sugar will draw out the lime oils from the peels, resulting in a very beautiful, almost citrus/floral note and the sugar will dissolve into a syrup,” according to Emde.

THE LEWISTON LEGEND

Like Hudson, Lewiston, New York, sits on a great river—in this case the Niagara. The town is a little north of (and below) Niagara Falls. Lewiston is 340 miles from Hudson, but still in the vast area called Upstate New York.

And like Hudson, Lewiston has a claim to the origin of the cocktail. It centers on a woman named Catherine “Kitty” Hustler. Did this early tavern keeper pluck the feather off a passing rooster and use it to stir a drink? Was that the first “cock’s tail” or “cocktail?”

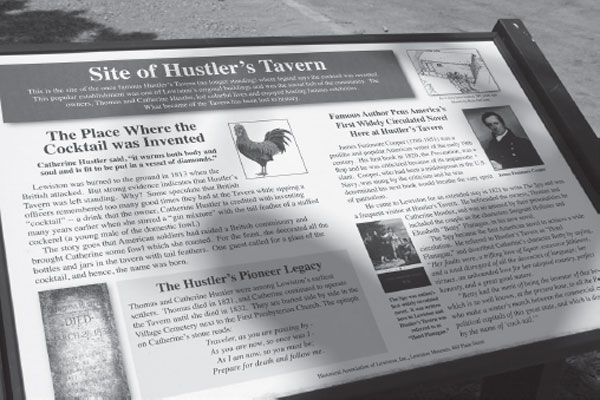

They seem to believe the story in Lewiston. They repeat it often—on a downtown historical marker, in the words of an actress who plays Hustler in history-themed walking tours and in this bit of narrative produced by the Niagara County Historical Society:

Gravestone of Catherine “Kitty” Hustler in Lewiston, with pewter cocktail goblet and feather. Author’s photo.

An interesting first in the annals of Niagara County is described in a story from the War of 1812. At that time, Thomas and Catherine Hustler operated a tavern in Lewiston that acquired a favorable international reputation among British, French and Americans, alike. Upon occasions, the Hustlers were even known to entertain a young naval officer named James Fenimore Cooper. Mr. and Mrs. Hustler stepped into bartending history when they supposedly began to serve drinks mixed from several liquors and stirred with a rooster’s tail feather. Upon tasting the concoction, a young French officer was said to have stood and toasted Mrs. Hustler saying, “Viva la cocktail!” Historians have conjectured that it was the cocktail that spared the Hustler tavern when the British burned Lewiston during the War of 1812. Some say that British officers couldn’t bear the thought of destroying the tavern where they first experienced this interesting libation. It is also assumed that James Fenimore Cooper, in his work, The Spy, patterned two of his characters, Sergeant Hollister and Betty Flanagan, after Mr. and Mrs. Hustler, Niagara County’s inventors of the cocktail.

Note the word “supposedly” in this story. How much of it is true? There is evidence that the Hustlers ran a tavern in Lewiston. They seem to have arrived in the early 1800s—he was a Revolutionary War veteran and she served as a sutler, someone who delivered supplies, including liquor, to the troops.

The Lewiston Historical Society and Museum has several records related to them. One item, museum curator Pam Hauth points out, is a claim filed against the government by Thomas Hustler, who wanted to be compensated for having his property burned by the British. So perhaps that part of the story—that the British left the tavern standing—is in question. (There is no evidence he was paid.)

For the most part, the tale of the rooster’s tail seems like just a good story. In the various versions told in and around Lewiston, details emerge or disappear and sometimes change. A version put out by the Lewiston Historical Society, for example, adds the suggestion that the drink itself was a “gin mixture.” It also repeats the bit about the British not burning the tavern:

Hustler’s Tavern in Lewiston was reportedly the only building left unscathed when the British invaded. Some say it was because the British officers remembered too many good times they had there sipping a “cocktail”—the drink that owner Catherine Hustler is credited with inventing when she stirred a “gin mixture” with the tail feather of a stuffed cockerel (a young male of the domestic fowl). She said it “warms both soul and body and is fit to be put in a vessel of diamonds.”

As ever, the tale keeps growing with each retelling. The historical society also packaged bits of the story of the Hustlers, the cocktail and Cooper and put them on a historic marker that stands today at the corner of Center and Eighth Streets, at the site where Hustler’s Tavern once stood. This version adds some background to the creation of the first cocktail: “The story goes that British soldiers had raided a British commissary and brought Catherine some fowl which she roasted. For the feast, she decorated all the bottles and jars in the tavern with tail feathers. One guest called for a glass of the cocktail, and hence, the name was born.”

If you visit Lewiston today, you don’t have to read the cocktail story on a marker or in an archive. Thanks to the Lewiston Council on the Arts, the story of Kitty Hustler and her role in drinks history comes alive.

In recent years, local actress Kathryn Serianni began playing Kitty Hustler in a series of walking, or living history tours, produced by the arts council in conjunction with the historical society. History buffs and other visitors hear the tale (or tales) of the cocktail, usually from the starting point at Hustler’s grave in the Village Cemetery, next to the First Presbyterian Church on Cayuga Street.

Marker from the Lewiston Historical Society at Center and Eight Streets in Lewiston, noting the site of Hustler’s Tavern and the “birthplace of the cocktail.” Author’s photo.

Serianni works from a couple of scripts. In one, she (as Kitty Hustler) takes the feather from a rooster to dress up a drink intended for the Marquis de Lafayette, a French military officer who had assisted the Americans in the Revolutionary War. (Lafayette did indeed visit Lewiston after the war. That much, the records support.) Lafayette enjoyed the new creation so much, Serianni/Hustler says, he jumped up and shouted, “Vive le Cocktail!”

Another of Serianni’s scripts involves no celebrities. It’s a more straightforward history of Hustler’s Tavern and its role in the cocktail. During a performance at the site of Kitty Hustler’s grave in June 2016, the account went like this:

I’m proud to say that we weren’t a fancy place. But we didn’t have to be. Most of our customers were soldiers from the fort or sailors waiting for their ships to be loaded and unloaded from Lewiston Landing. Now, Hustler’s Tavern helped many of those first settlers spend those long winter evenings here in the village of Lewiston. And one night—one special night—the customers were sitting around bored and starting to snipe at each other. So I thought I’d fix them up something special. I took one of my fine goblets and I put in a little gin and a little bit of mint and “something else” and I plucked the tail feather of a rooster that was lying dead on the bar. No matter how many times I told those hunters to leave their game outside, they’d bring them right in! Anyway, I plucked the tail off that rooster and gave the drink a stir and, lo and behold, the cocktail was invented. Right here in little Lewiston!

Lewiston actress Kathryn Serianni, portraying “Kitty” Hustler, said to be the inventor of the cocktail. Lewiston Council on the Arts.

KITTY HUSTLER’S COCKTAIL: WHAT WAS IT?

We’ll probably never know Hustler’s original recipe (if there even was one). But we do know what a “gin mixture,” as mentioned in Lewiston’s historic annals and markers, could have been. In the early 1800s, in most taverns, inns and even some homes, you could find such drinks as gin toddies, gin sangarees and gin slings.

We’ve already provided author Eric Felten’s version of a Bittered Gin Sling. Here, from the first-ever printed cocktail guide, compiled in 1862 by Upstate native and nineteenth-century celebrity bartender Jerry Thomas, are three gin mixtures already popular by that era.

Gin Toddy

Adapted from How to Mix Drinks, by Jerry Thomas (1862 edition)

1 teaspoon sugar

½ wineglass water (1 to 2 ounces)

1 do. gin (2 ounces)

1 small lump ice

Mix in a small bar glass and stir with a spoon.

For a Gin Sling: Thomas’s recipe is the same as for the Gin Toddy, but with sprinkled nutmeg on top.

For a Gin Sangaree: Follow the recipe for the Gin Toddy. Fill the glass two-thirds with ice and then float about a teaspoon of port wine on top.

You can search every bar and restaurant in Lewiston today and you won’t find anyone who is using the feather of a rooster (dead or alive) to stir a mixed drink. That doesn’t mean local bartenders aren’t aware of the local lore.

“I have gone to every restaurant in Lewiston—everybody seems to know that the cocktail was invented here,” said Eva Nicklas, a staffer for the Lewiston Council for the Arts who helps coordinate the tours that Serriani (as Kitty Hustler) and others lead around town.

The story even spawned a short-lived Lewiston Cocktail Festival to celebrate the historic events. (The festival was held through 2015, and organizers hope it will return.) Interestingly, the festival’s website says Hustler “plucked a peacock quill from the back wall of a Lewiston bar she was tending,” but as we’ve said, everyone in town seems to add their own element to the story.

The Water Street Landing restaurant overlooking the Niagara River helped spearhead the cocktail festival. “We started the cocktail fest to bring some swagger to the place where the cocktail was invented,” said Matthew Ott, general manager. “We decided to let the bars compete to see who is the best in the home of the cocktail.”

Water Street Landing won the contest in its first year with a drink called the Hibiscus Kiss, made with Absolut Hibiscus, a flavored vodka. Since that liquor is hard to find, Ott made us another drink to showcase the bar’s (and Lewiston’s) modern cocktail capabilities.

Pineapple Upside Down Cake

From Matthew Ott, Water Street Landing, Lewiston

1 ounce vodka

1 ounce coconut rum (Blue Chair Bay)

2 ounces pineapple juice

Maraschino cherry juice

Put the vodka and rum into an ice-filled shaker. Add the pineapple juice after first shaking it to foam it up. Shake and strain into a chilled martini glass. Using a straw, draw about an inch or two of maraschino cherry juice and then release it into the glass.

Note: Despite its tropical-sounding name, Blue Chair Bay rum has an Upstate connection. It is produced in Barbados but bottled at LiDestri Food & Beverage in Rochester. The brand is owned by country music superstar Kenny Chesney.

THE COCKTAIL, THE SPY AND

JAMES FENIMORE COOPER

Catherine “Kitty” Hustler was real enough. But she’s better known as the inspiration for a character in an early American work of fiction. She became “Betty Flanagan” in the novel The Spy, by James Fenimore Cooper. The Spy is a Revolutionary War story. The central plot is about a man suspected of, well, of being a British spy. In the book, Cooper describes Flanagan as “female sutler,” “washerwoman” and “petticoat doctor” to the American troops in the vicinity of the “Four Corners,” now Elmsford, Westchester County. (A sutler is someone who delivers supplies to army troops.)

Here’s Cooper’s description of this secondary, but memorable, character:

Betty was well known to every trooper in the corps, could call each by his Christian or nickname, as best suited her fancy; and, although absolutely intolerable to all whom habit had not made familiar with her virtues, was a genial favorite with these partisan warriors. Her faults were, a trifling love of liquor, excessive filthiness and a total disregard of all the decencies of language; her virtues, an unbounded love for her adopted country, perfect honesty when dealing on certain known principles with the soldiery, and great good nature.

Then Cooper comes to the point that lands Flanagan in the thick of the cocktail conversation:

Added to these, Betty had the merit of being the inventor of that beverage which is so well known, at the present hour, to all the patriots who make a winter’s march between the commercial and political capitals of this great state, and which is distinguished by the name of “cocktail.” Elizabeth Flanagan was peculiarly well qualified, by education and circumstances, to perfect this improvement in liquors, having been literally brought up on its principal ingredient, and having acquired from her Virginian customers the use of mint, from its flavor in a julep to the its height of renown in the article in question.

And according to Cooper, what did Betty Flanagan have to say about her own creation? “There’s that within that’s fit to be put in vissils of di’monds,” she says, putting some dialect in the words often repeated today in Lewiston.

So, what’s the connection between Elizabeth “Betty” Flanagan, Catherine “Kitty” Hustler and James Fenimore Cooper? And how do we get from Four Corners in Westchester County to Lewiston, on the Canadian border?

On the historic marker at the site of Hustler’s Tavern, the corner of Center and Eighth Streets in Lewiston, the text describes Cooper’s efforts to achieve literary success after the failure of his first novel, which was considered “unpatriotic”:

Cooper, who had been a midshipman in the U.S. Navy, was stung by the criticism and he was determined his next book would breathe the very spirit of patriotism. He came to Lewiston for an extended stay in 1821 to write The Spy and was a frequent visitor at Hustler’s Tavern. He befriended the owners, Thomas and Catherine Hustler, and was so amused by their personalities he included the couple as the characters Sergeant Hollister and Elizabeth “Betty” Flanagan, in his new novel.

This book, the marker states, was a success. As history, it leaves some question marks. This account, like many others, puts the year of Cooper’s stay in Lewiston as 1821. Many other accounts say he stayed there—and encountered Kitty Hustler—during the War of 1812. That would mean his visit could have been no later than early 1815 or earlier.

Of course, history and fiction often intertwine. Consider a fanciful historical narrative titled “Something of Yesterday,” one of the source materials used by Serriani for her portrayal of Hustler.

It starts with a description of the anger and disappointment that the people of Lewiston felt in 1821, when their town lost out to the nearby community of Lockport in the selection of a county seat for Niagara. On this particular night, the men in the tavern weren’t drinking much. The account gives another version of Hustler’s “cock-tail” drink. “Into the tankard she pours a large allowance of gin and some drops of herbed wine and to mix the two she plucks the tail feather of a stuffed cock pheasant.…Her blue eyes now dancing she slides the tankard across the oaken table…‘Drink yee,’ says she, ‘’twill warm both sowl and body.’”

And where was James Fenimore Cooper? “Aside and alert in a corner sits a traveler most interested in the evening’s proceedings,” this story continues. “Before the sun comes up, Fennimore [sic] Cooper, writing at a small desk in an upstairs room, fashions Betty Flanagan of his novel, “The Spy,“ from this very Katherine Hustler of Lewiston, who gave to the land its first cock-tail.”

New York Times writer William Grimes, before writing his 2001 cocktail history, Straight Up or On the Rocks, offered this assessment of the Betty (or Betsy) Flanagan legend in a New York Times column dated August 25, 1991:

The word cocktail has inspired perhaps the most notorious fraud of all—the Flanagan Fallacy. Virtually every account of the cocktail’s origins drags in Betsy Flanagan, an innkeeper during the Revolutionary War who stirred a drink with a rooster tail and dubbed it a cocktail. Some versions place the inn at Four Corners, in Westchester County, N.Y.; others locate the sacred ground a few miles away in Elmsford. For the real location, turn to Chapter 16 of James Fenimore Cooper’s “Spy,” published in 1821 but set in the 1780’s. There, Flanagan and feather first appear, as real as fiction.

One more thing about Kitty Hustler, the linchpin for this bit of Upstate cocktail lore, both fact and fiction. She appears to have been a “wild woman,” according to Eva Nicklas of the Lewiston Council of the Arts. Hustler’s roles as a supplier of goods to troops and the keeper of a tavern would have kept her from being considered genteel in those days, underscored by Cooper’s references to the character Betty Flanagan’s drinking, dirtiness and indecent language.

Hustler’s grave is well marked in the Lewiston village cemetery, next to her husband’s. Along with her name and date of death, it bears this inscription:

Traveler as you are passing by

As you are now so once was I

As I am now so you must be

Prepare for death and follow me

To confirm Nicklas’s point about her character, many around Lewiston add these lines:

To follow her I’m not content,

until I know which way she went